Alice Allison Dunnigan, Rosa Parks and the Selma March

Before the Selma march on March 7, 1965, there were many brave African-Americans who fought for their civil rights and human right as a whole. But long before there was an African-American woman named Alice Allison Dunnigan who was born in 1906 and died in 1983. She fought for civil rights. She was an African-American journalist, and author. She was the first African-American female correspondent to receive White House credentials, and the first black female member of the Senate and House of Representatives press galleries.

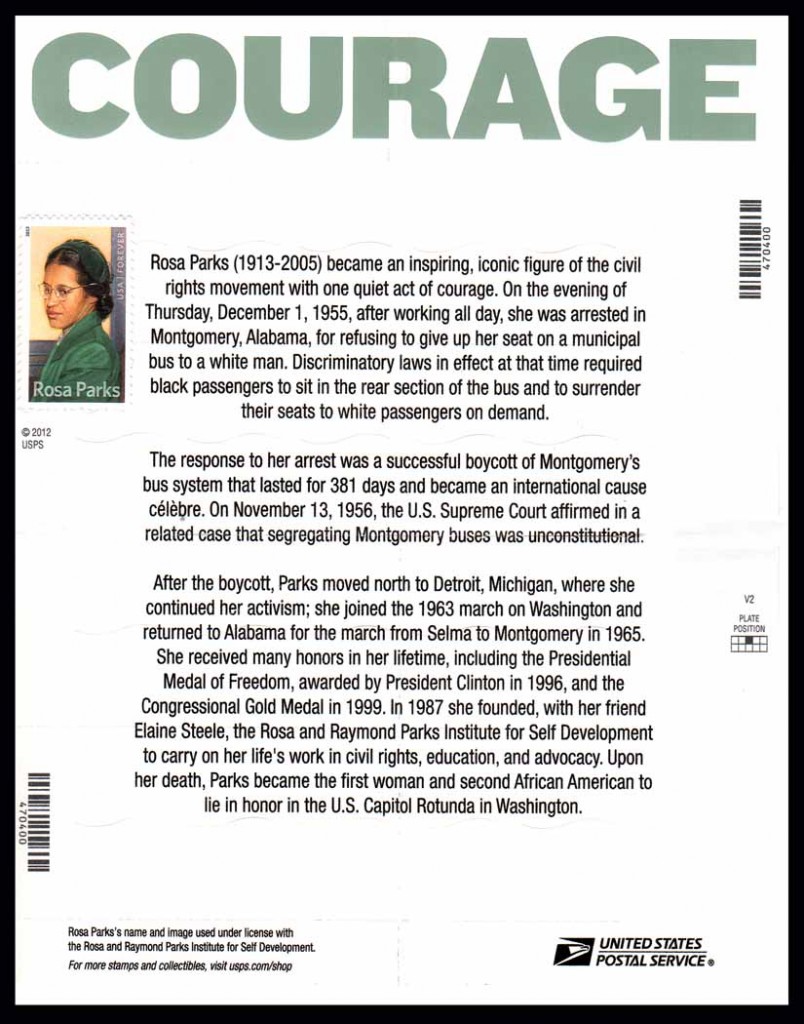

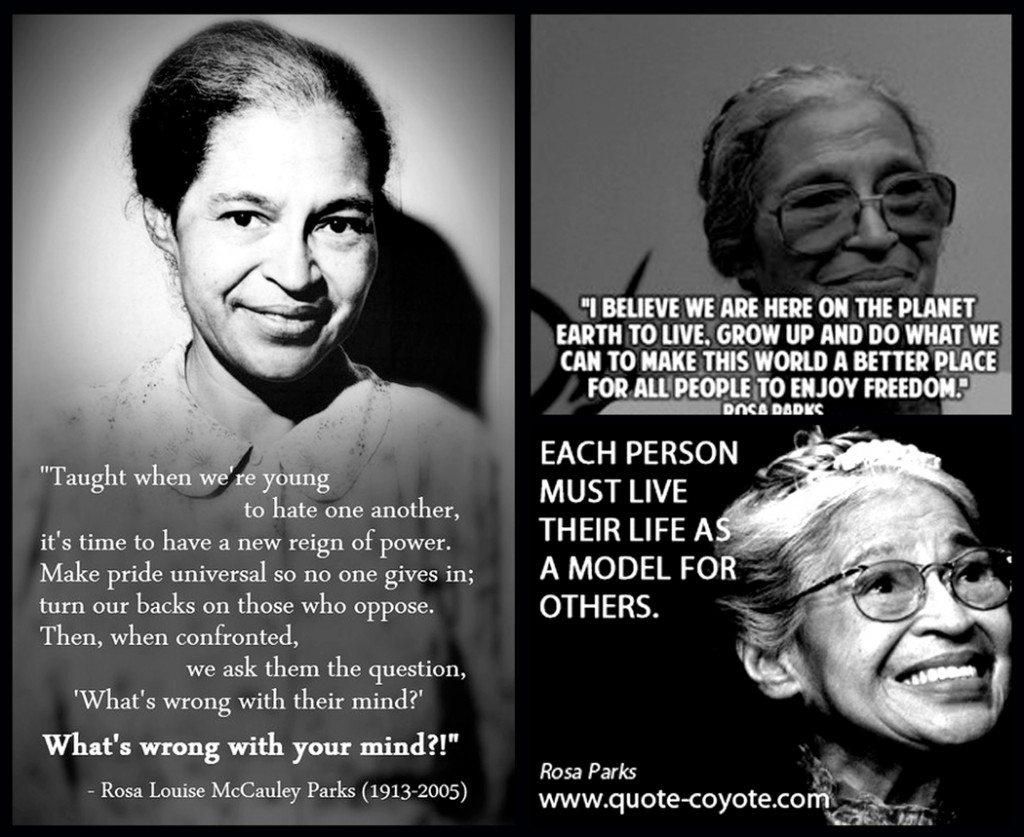

Before the Selma march, Rosa Parks who was born in 1913 and died in 2005, showed her courage to fight for civil rights by refusing to give up her seat on the bus to a white man in 1955 which activated a stronger movements of civil right for American African in USA.

There are many women and men, black and white who contributed to the cause of civil right in US. But I picked only the two women above because their lifelong contributions. They are good examples for all humankind everywhere on earth to speak out for the equality of all citizens of the world.

The following are the life stories of Alice Allison Dunnigan, Rosa Parks and the Selma to Montgomery March as described in Wikipeadia, usslave.blogspot.com, United States Postal Service stamp information, and other sources.

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Monday, March 30, 2015

Alice Allison Dunnigan

Alice Allison was born on April 27, 1906 near Russellville, Kentucky , died on May 6, 1983 (aged 77)

Alice Allison was born on April 27, 1906 near Russellville, Kentucky , died on May 6, 1983 (aged 77)

Washington, D.C.

Alice Allison Dunnigan (1906–1983)[1] was an African-American journalist, civil rights activist and author.[2] She was the first African-American female correspondent to receive White House credentials,[3] and the first black female member of the Senate and House of Representatives press galleries. She has written an autobiography entitled Alice A. Dunnigan: A Black Woman’s Experience.[3] She also has a Kentucky State Historical Commission marker dedicated to her.[4]

Alice chronicled the decline of Jim Crow during the 1940s and 1950s, which influenced her to become a civil rights activist.[2] She was inducted into the Kentucky Hall of Fame in 1982.[5]

During her time as a reporter, she became the first black journalist to accompany a president while traveling, covering Harry S. Truman‘s 1948 campaign trip.[5]

Biography

Alice was born April 27, 1906 near Russellville, Kentucky to Willie and Lena Pittman Allison.[5] Her father was a sharecropper and her mother took in laundry for a living.[6]

At age 13, she began writing for the Owensboro Enterprise.[3] Her dream was to experience the world through the life of a newspaper reporter.[6]

After completing a teaching course at Kentucky Normal and Industrial Institute,[7] she taught Kentucky History in the Todd County School System, which was segregated at the time.[3] She noticed that her class was not aware of the African American contributions to the Commonwealth, she started to prepare Kentucky Fact Sheets as supplements to required text.[3] They were collected and formed into a manuscript in 1939, but finally published in 1982 with the title The Fascinating Story of Black Kentuckians: Their Heritage and Tradition.[3]

From 1947 to 1961, she served as chief of the Washington bureau of the Associated Negro Press. In 1947 she was a member of the Senate and House of Representatives press galleries, and in 1948 she was made a White House correspondent. In 1961 she was named education consultant to the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity. From 1967 to 1970 she was as an associate editor with the President’s Commission on Youth Opportunity.[8]

Dunnigan was named education consultant to the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity in 1961 and was an associate editor with the President’s Commission on Youth Opportunity from 1967 to 1970. Dunnigan was the first black female member of the Senate and House of Representatives press galleries (1947), and the first black female White House correspondent in 1948.[8]

Biography #2

Dunnigan reported on Congressional hearings where blacks were referred to as “niggers,” was barred from covering a speech by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in a whites-only theater, and was not allowed to sit with the press to cover Senator Robert A. Taft‘s funeral — she covered the event from a seat in the servant’s section. Dunnigan was known for her straight-shooting reporting style. Politicians routinely avoided answering her difficult questions, which often involved race issues.

Dunnigan’s father was a sharecropper who raised tobacco, her mother took in laundry. She and her half-brother, Russell, were raised in a strict household with an emphasis on a strong work ethic. She had few friends as a child, and as a teenager was prohibited from having boyfriends. She started attending school one day a week at age four, and learned to read before entering the first grade.

Dunnigan’s career in journalism began at age 13, when she started writing one-sentence news items for the local Owensboro Enterprise newspaper. She completed the ten years available to blacks in the segregated Russellville school system, but her parents saw no benefit in allowing their daughter to continue her education. A Sunday school teacher intervened, and Dunnigan was allowed to attend college. By the time she had reached college, Dunnigan had set her sights on becoming a teacher, and completed the teaching course at what is now Kentucky State University. Dunnigan was a teacher in Kentucky public schools from 1924 to 1942. A four-year marriage to Walter Dickenson of Mount Pisgeh ended in divorce in 1930. She married Charles Dunnigan, a childhood friend, on January 8, 1932. The couple had one child, Robert William, and separated in 1953.

As a young teacher in the segregated Todd County School system, Dunnigan taught courses in Kentucky history. She quickly learned that her students were almost completely ignorant of the historic contributions of African Americans to the state of Kentucky. She started preparing “Kentucky Fact Sheets” and handing them out to her students as supplements to the required text. These papers were collected for publication in 1939, but no publisher was willing to take them to press. Associated Publishers Inc. finally published the articles in 1982 as The Fascinating Story of Black Kentuckians: Their Heritage and Tradition. The meager pay she earned teaching forced her to work numerous menial jobs during the summer months, when school was not in session. She washed the tombstones in the white cemetery while working four hours a day in a dairy, cleaning house for a family, and doing washing at night for another family, earning a total of about seven dollars a week.

A call for government workers went out in 1942, and Dunnigan moved to Washington, D.C., during World War II seeking better pay and a government job. She worked as a federal government employee from 1942 to 1946, and took a year of night courses at Howard University. In 1946 she was offered a job writing for the Chicago Defender as a Washington correspondent. The Defender was a black-owned weekly that did not use the words “Negro” or “black” in its pages. Instead, African Americans were referred to as “the Race” and black men and women as “Race men and Race women.” Unsure of Dunnigan’s abilities, the editor of the Defender paid her much less than her male counterparts until she could prove her worth. She supplemented her income with other writing jobs.

As a writer for the Associated Negro Press news service, Dunnigan sought press credentials to cover Congress and the Senate. The government denied her request on the grounds that she was writing for a weekly newspaper, and reporters covering the U.S. Capitol were required to write for daily publications. Six months later, however, she was granted press clearance, becoming the first African-American woman to gain accreditation. In 1947 she was named bureau chief of the Associate Negro Press, a position she held for 14 years.

In 1948 Dunnigan was one of three African Americans and one of two women in the press corps that followed President Harry S. Truman’s Western campaign, paying her own way to do it. Also that year, she became the first African-American female White House correspondent, and was the first black woman elected to the Women’s National Press Club. Her association with this and other organizations allowed her to travel extensively in the United States and to Canada, Israel, South America, Africa, Mexico, and the Caribbean. She was honored by Haitian President François Duvalier for her articles on Haiti.

During her years covering the White House, Dunnigan suffered many of the racial indignities of the time, but also earned a reputation as a hard-hitting reporter. She was barred from entering certain establishments to cover President Eisenhower, and had to sit with the servants to cover Senator Taft’s funeral. When she attended formal White House functions, she was mistaken for the wife of a visiting dignitary; no one could imagine a black woman attending such an event on her own. During Eisenhower’s two administrations, the president resorted first to not calling on her and later to asking for her questions beforehand because she was known to ask such difficult questions, often about race. No other member of the press corps was required to submit their questions before a press conference, and Dunnigan refused. When Kennedy took office, he welcomed Dunnigan’s tough questions and answered them frankly.

In 1960 Dunnigan left her seat in the press galleries to take a position on Lyndon B. Johnson’s campaign for the Democratic nomination. John F. Kennedy won the nomination, but chose Johnson as his running mate and named Dunnigan education consultant of the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity. She remained with the committee until 1965. Between 1966 and 1967 she worked as an information specialist for the Department of Labor and then as an editorial assistant for the President’s Council of Youth Opportunity. When Richard M. Nixon took over the presidency in 1968, Dunnigan, as well as the rest of the Democratic administration, found themselves on their way out of the White House to make way for Nixon’s Republican team.

After her White House days, Dunnigan returned to writing, this time about herself. Her autobiography, A Black Woman’s Experience: From Schoolhouse to White House, was published in 1974. As its title indicates, the book is an exploration of Dunnigan’s life from her childhood in rural Kentucky to her pioneering work both covering the White House and inside it. Despite her extensive work in government and politics, Dunnigan was most proud of her work in journalism, and received more than 50 journalism awards. She died of ischemic bowel disease on May 6, 1983, in Washington, D.C.

This page was last modified on 30 January 2015, at 16:02.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Allison_Dunnigan

Rosa Parks

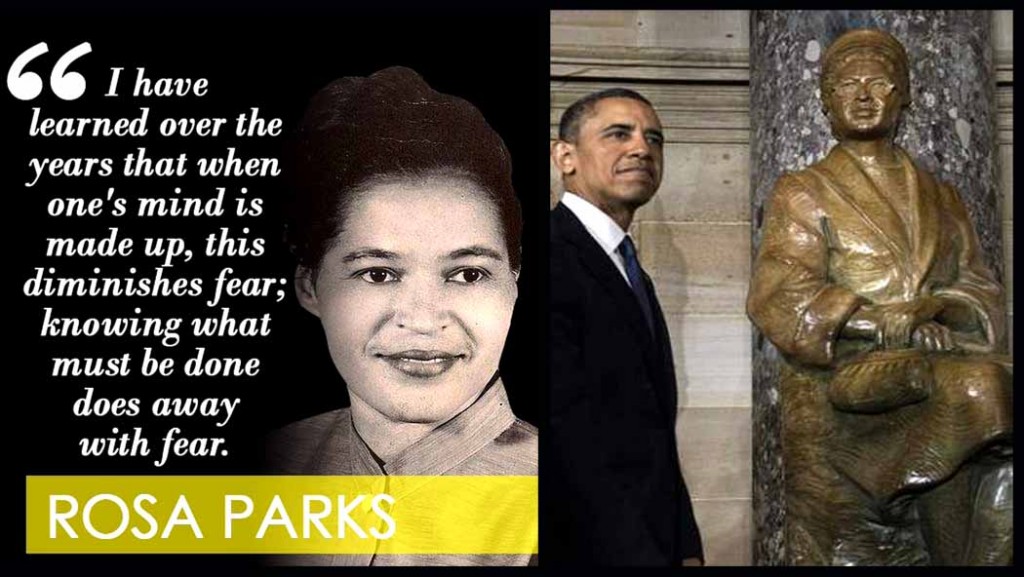

Right: President Barack Obama dedicated Rosa Parkers statue on Wednesday, February.27, 2013

Right: Rosa Parks and actor & singer, Harry Belafonte

Left: Rosa Parks and Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Rosa Parks

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Rosa Parks was born on February 4, 1913, in Rosa Louise McCauley, died on October 24, 2005 (aged 92), in Detroit, Michigan, U.S.

Occupation Civil rights activist

Known for Montgomery Bus Boycott

Home town Tuskegee, Alabama

Spouse(s) Raymond Parks (1932–1977)

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an African-American Civil Rights activist, whom the United States Congress called “the first lady of civil rights” and “the mother of the freedom movement”.[1] Her birthday, February 4, and the day she was arrested, December 1, have both become Rosa Parks Day, commemorated in both California and Ohio.

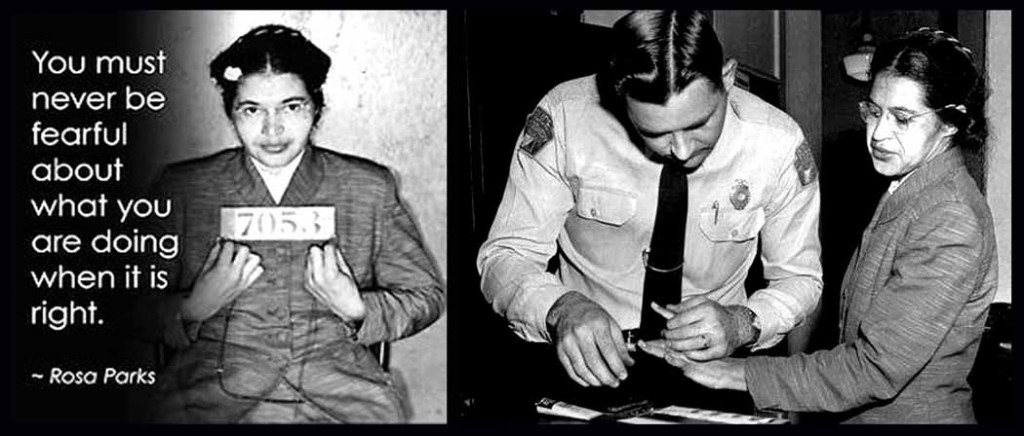

On December 1, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, Parks refused to obey bus driver James F. Blake‘s order to give up her seat in the colored section to a white passenger, after the white section was filled. Parks was not the first person to resist bus segregation. Others had taken similar steps, including Bayard Rustin in 1942,[2] Irene Morgan in 1946, Sarah Louise Keys in 1952, and the members of the ultimately successful Browder v. Gayle lawsuit (Claudette Colvin, Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith) who were arrested in Montgomery for not giving up their bus seats months before Parks. NAACP organizers believed that Parks was the best candidate for seeing through a court challenge after her arrest for civil disobedience in violating Alabama segregation laws, although eventually her case became bogged down in the state courts while the Browder v. Gayle case succeeded.[3][4]

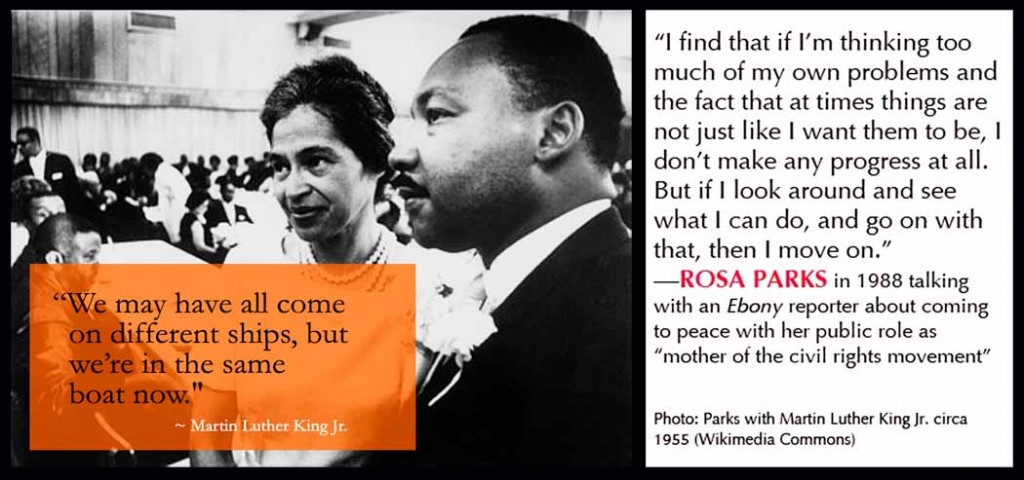

Parks’ act of defiance and the Montgomery Bus Boycott became important symbols of the modern Civil Rights Movement. She became an international icon of resistance to racial segregation. She organized and collaborated with civil rights leaders, including Edgar Nixon, president of the local chapter of the NAACP; and Martin Luther King, Jr., a new minister in town who gained national prominence in the civil rights movement.

At the time, Parks was secretary of the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP. She had recently attended the Highlander Folk School, a Tennessee center for training activists for workers’ rights and racial equality. She acted as a private citizen “tired of giving in”. Although widely honored in later years, she also suffered for her act; she was fired from her job as a seamstress in a local department store, and received death threats for years afterwards.

Shortly after the boycott, she moved to Detroit, where she briefly found similar work. From 1965 to 1988 she served as secretary and receptionist to John Conyers, an African-American U.S. Representative. She was also active in the Black Power movement and the support of political prisoners in the US.

After retirement, Parks wrote her autobiography and lived a largely private life in Detroit. In her final years, she suffered from dementia. Parks received national recognition, including the NAACP’s 1979 Spingarn Medal, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Congressional Gold Medal, and a posthumous statue in the United States Capitol’s National Statuary Hall. Upon her death in 2005, she was the first woman and second non-U.S. government official to lie in honor at the Capitol Rotunda.

Early years

Rosa Parks was born Rosa Louise McCauley in Tuskegee, Alabama, on February 4, 1913, to Leona (née Edwards), a teacher, and James McCauley, a carpenter. She was of African ancestry, though one her great-grandfathers was Scots-Irish and one of her great-grandmothers was a slave of Native American descent.[5][6] She was small as a child and suffered poor health with chronic tonsillitis. When her parents separated, she moved with her mother to Pine Level, just outside the state capital, Montgomery. She grew up on a farm with her maternal grandparents, mother, and younger brother Sylvester. They all were members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), a century-old independent black denomination founded by free blacks in Philadelphia in the early nineteenth century.

McCauley attended rural schools[7] until the age of eleven. As a student at the Industrial School for Girls in Montgomery, she took academic and vocational courses. Parks went on to a laboratory school set up by the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes for secondary education, but dropped out in order to care for her grandmother and later her mother, after they became ill.[8]

Around the turn of the 20th century, the former Confederate states had adopted new constitutions and electoral laws that effectively disfranchised black voters and, in Alabama, many poor white voters as well. Under the white-established Jim Crow laws, passed after Democrats regained control of southern legislatures, racial segregation was imposed in public facilities and retail stores in the South, including public transportation. Bus and train companies enforced seating policies with separate sections for blacks and whites. School bus transportation was unavailable in any form for black schoolchildren in the South, and black education was always underfunded.

Parks recalled going to elementary school in Pine Level, where school buses took white students to their new school and black students had to walk to theirs:

I’d see the bus pass every day… But to me, that was a way of life; we had no choice but to accept what was the custom. The bus was among the first ways I realized there was a black world and a white world.[9]

Although Parks’ autobiography recounts early memories of the kindness of white strangers, she could not ignore the racism of her society. When the Ku Klux Klan marched down the street in front of their house, Parks recalls her grandfather guarding the front door with a shotgun.[10] The Montgomery Industrial School, founded and staffed by white northerners for black children, was burned twice by arsonists. Its faculty was ostracized by the white community.

Repeatedly bullied by white children in her neighborhood, Parks often fought back physically. She later said that “As far back as I remember, I could never think in terms of accepting physical abuse without some form of retaliation if possible.” [11]

In 1932, Rosa married Raymond Parks, a barber from Montgomery. He was a member of the NAACP, which at the time was collecting money to support the defense of the Scottsboro Boys, a group of black men falsely accused of raping two white women. Rosa took numerous jobs, ranging from domestic worker to hospital aide. At her husband’s urging, she finished her high school studies in 1933, at a time when less than 7% of African Americans had a high school diploma. Despite the Jim Crow laws and discrimination by registrars, she succeeded in registering to vote on her third try.

In December 1943, Parks became active in the Civil Rights Movement, joined the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP, and was elected secretary. She later said, “I was the only woman there, and they needed a secretary, and I was too timid to say no.”[12] She continued as secretary until 1957. She worked for the local NAACP leader E.D. Nixon, even though he maintained that “Women don’t need to be nowhere but in the kitchen.”[13] When Parks asked “Well, what about me?”, he replied “I need a secretary and you are a good one.”[13]

In 1944, in her capacity as secretary, she investigated the gang-rape of Recy Taylor, a black woman from Abbeville, Alabama. Parks and other civil rights activists organized the “Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor”, launching what the Chicago Defender called “the strongest campaign for equal justice to be seen in a decade.”[14]

Although never a member of the Communist Party, she attended meetings with her husband. The notorious Scottsboro case had been brought to prominence by the Communist Party.[15]

In the 1940s, Parks and her husband were members of the Voters’ League. Sometime soon after 1944, she held a brief job at Maxwell Air Force Base, which, despite its location in Montgomery, Alabama, did not permit racial segregation because it was federal property. She rode on its integrated trolley. Speaking to her biographer, Parks noted, “You might just say Maxwell opened my eyes up.” Parks worked as a housekeeper and seamstress for Clifford and Virginia Durr, a white couple. Politically liberal, the Durrs became her friends. They encouraged—and eventually helped sponsor—Parks in the summer of 1955 to attend the Highlander Folk School, an education center for activism in workers’ rights and racial equality in Monteagle, Tennessee. There Parks was mentored by the veteran organizer Septima Clark.[16]

In August 1955, black teenager Emmett Till was brutally murdered after reportedly flirting with a young white woman while visiting relatives in Mississippi.[17] On November 27, 1955, Rosa Parks attended a mass meeting in Montgomery that addressed this case as well as the recent murders of the activists George W. Lee and Lamar Smith. The featured speaker was T. R. M. Howard, a black civil rights leader from Mississippi who headed the Regional Council of Negro Leadership.[18] The discussions concerned actions blacks could take to gain respect for their rights.

Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Main article: Montgomery Bus Boycott

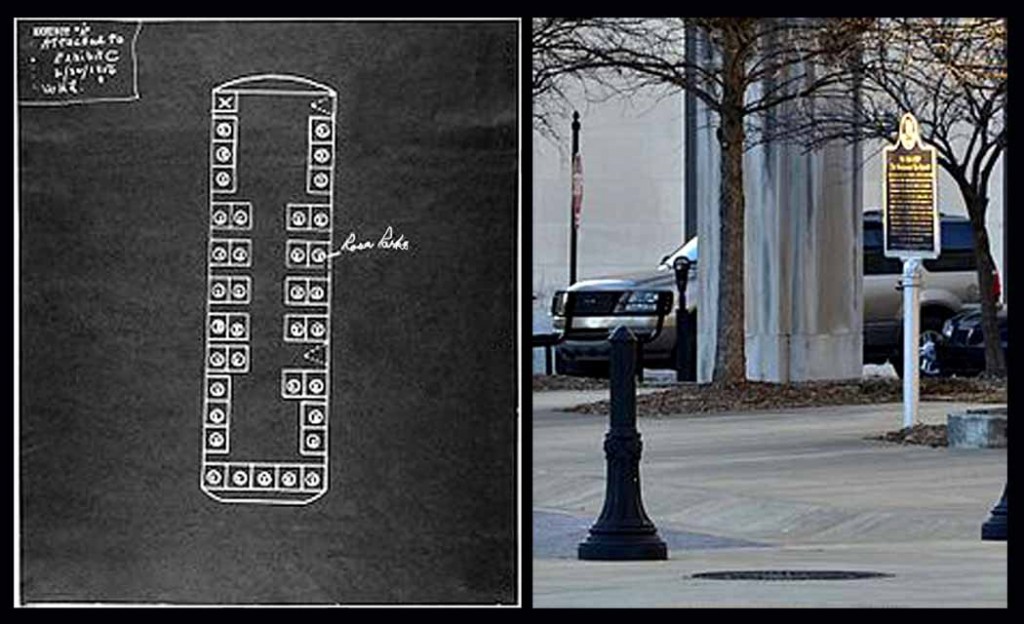

Left: Seat layout on the bus where Parks sat, December 1, 1955

Left: Seat layout on the bus where Parks sat, December 1, 1955

Right: A plaque entitled “The Bus Stop” at Dexter Ave. and Montgomery St.—the place Rosa Parks boarded the bus—pays tribute to her and the success of the Montgomery bus boycott.

Montgomery buses: law and prevailing customs

In 1900, Montgomery had passed a city ordinance to segregate bus passengers by race. Conductors were empowered to assign seats to achieve that goal. According to the law, no passenger would be required to move or give up his seat and stand if the bus was crowded and no other seats were available. Over time and by custom, however, Montgomery bus drivers adopted the practice of requiring black riders to move when there were no white-only seats left.

The first four rows of seats on each Montgomery bus were reserved for whites. Buses had “colored” sections for black people generally in the rear of the bus, although blacks comprised more than 75% of the ridership. The sections were not fixed but were determined by placement of a movable sign. Black people could sit in the middle rows until the white section filled; if more whites needed seats, blacks were to move to seats in the rear, stand, or, if there was no room, leave the bus. Black people could not sit across the aisle in the same row as white people. The driver could move the “colored” section sign, or remove it altogether. If white people were already sitting in the front, black people had to board at the front to pay the fare, then disembark and reenter through the rear door.

For years, the black community had complained that the situation was unfair. Parks said, “My resisting being mistreated on the bus did not begin with that particular arrest…I did a lot of walking in Montgomery.”[7]

One day in 1943, Parks boarded the bus and paid the fare. She then moved to her seat but driver James F. Blake told her to follow city rules and enter the bus again from the back door. Parks exited the vehicle and waited for the next bus, determined never to ride with Blake again.[19]

Her refusal to move

After working all day, Parks boarded the Cleveland Avenue bus around 6 p.m., Thursday, December 1, 1955, in downtown Montgomery. She paid her fare and sat in an empty seat in the first row of back seats reserved for blacks in the “colored” section. Near the middle of the bus, her row was directly behind the ten seats reserved for white passengers. Initially, she did not notice that the bus driver was the same man, James F. Blake, who had left her in the rain in 1943. As the bus traveled along its regular route, all of the white-only seats in the bus filled up. The bus reached the third stop in front of the Empire Theater, and several white passengers boarded.

Left: The No. 2857 bus on which Parks was riding before her arrest (a GM “old-look” transit bus, serial number 1132), is now a museum exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum.

Left: The No. 2857 bus on which Parks was riding before her arrest (a GM “old-look” transit bus, serial number 1132), is now a museum exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum.

Blake noted that two or three white passengers were standing, as the front of the bus had filled to capacity. He moved the “colored” section sign behind Parks and demanded that four black people give up their seats in the middle section so that the white passengers could sit. Years later, in recalling the events of the day, Parks said, “When that white driver stepped back toward us, when he waved his hand and ordered us up and out of our seats, I felt a determination to cover my body like a quilt on a winter night.”[20]

By Parks’ account, Blake said, “Y’all better make it light on yourselves and let me have those seats.”[21] Three of them complied. Parks said, “The driver wanted us to stand up, the four of us. We didn’t move at the beginning, but he says, ‘Let me have these seats.’ And the other three people moved, but I didn’t.”[22] The black man sitting next to her gave up his seat.[23]

Parks moved, but toward the window seat; she did not get up to move to the redesignated colored section.[23] Blake said, “Why don’t you stand up?” Parks responded, “I don’t think I should have to stand up.” Blake called the police to arrest Parks. When recalling the incident for Eyes on the Prize, a 1987 public television series on the Civil Rights Movement, Parks said, “When he saw me still sitting, he asked if I was going to stand up, and I said, ‘No, I’m not.’ And he said, ‘Well, if you don’t stand up, I’m going to have to call the police and have you arrested.’ I said, ‘You may do that.’”[24]

Rosa Parks’ arrest

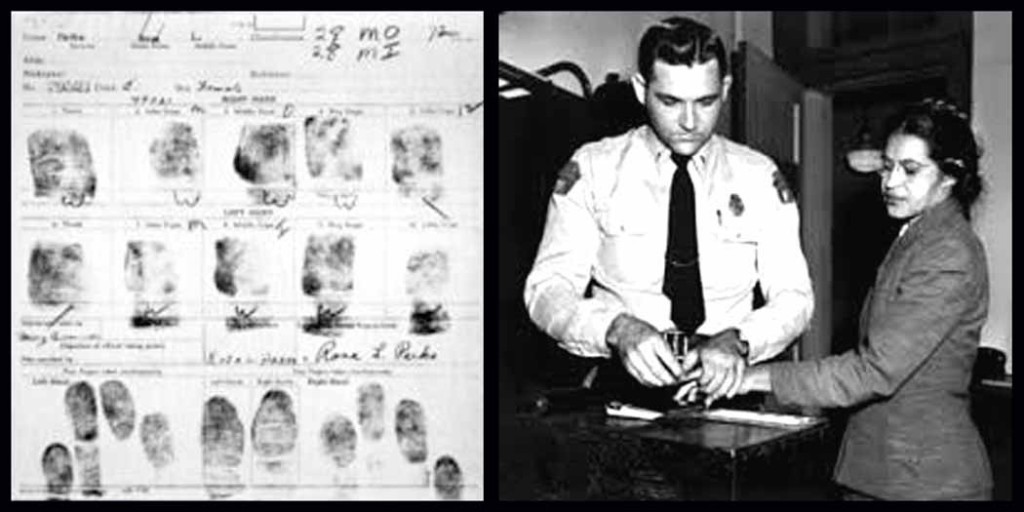

Right: Rosa Parks finger printed

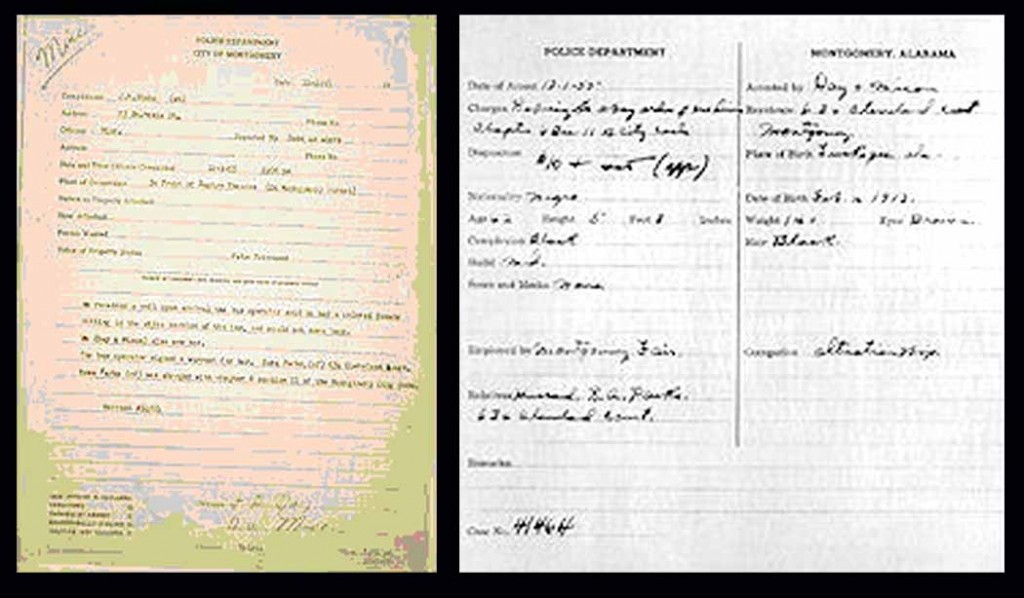

Left:Police report on Parks, December 1, 1955, page 1

Left:Police report on Parks, December 1, 1955, page 1

Right: Police report on Parks, December 1, 1955, page 2

Left: Fingerprint card of Parks

Left: Fingerprint card of Parks

During a 1956 radio interview with Sydney Rogers in West Oakland several months after her arrest, Parks said she had decided, “I would have to know for once and for all what rights I had as a human being and a citizen.”[25]

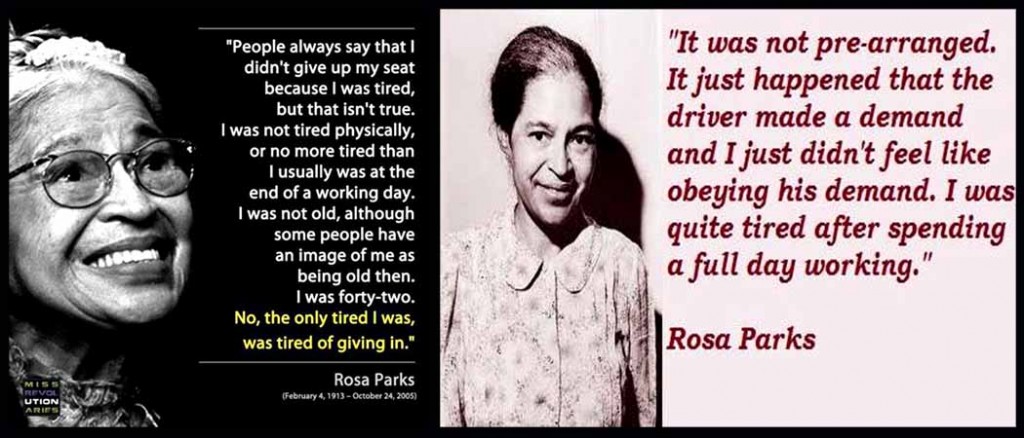

In her autobiography, My Story she said:

People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.[26]

When Parks refused to give up her seat, a police officer arrested her. As the officer took her away, she recalled that she asked, “Why do you push us around?” She remembered him saying, “I don’t know, but the law’s the law, and you’re under arrest.”[27] She later said, “I only knew that, as I was being arrested, that it was the very last time that I would ever ride in humiliation of this kind…”[22]

Parks was charged with a violation of Chapter 6, Section 11 segregation law of the Montgomery City code,[28] although technically she had not taken a white-only seat; she had been in a colored section.[29] Edgar Nixon, president of the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP and leader of the Pullman Porters Union, and her friend Clifford Durr bailed Parks out of jail the next evening.[30]

Montgomery Bus Boycott

Nixon conferred with Jo Ann Robinson, an Alabama State College professor and member of the Women’s Political Council (WPC), about the Parks case. Robinson believed it important to seize the opportunity and stayed up all night mimeographing over 35,000 handbills announcing a bus boycott. The Women’s Political Council was the first group to officially endorse the boycott.

On Sunday, December 4, 1955, plans for the Montgomery Bus Boycott were announced at black churches in the area, and a front-page article in the Montgomery Advertiser helped spread the word. At a church rally that night, those attending agreed unanimously to continue the boycott until they were treated with the level of courtesy they expected, until black drivers were hired, and until seating in the middle of the bus was handled on a first-come basis.

The next day, Parks was tried on charges of disorderly conduct and violating a local ordinance. The trial lasted 30 minutes. After being found guilty and fined $10, plus $4 in court costs,[22] Parks appealed her conviction and formally challenged the legality of racial segregation. In a 1992 interview with National Public Radio‘s Lynn Neary, Parks recalled:

I did not want to be mistreated, I did not want to be deprived of a seat that I had paid for. It was just time… there was opportunity for me to take a stand to express the way I felt about being treated in that manner.[31] I had not planned to get arrested. I had plenty to do without having to end up in jail. But when I had to face that decision, I didn’t hesitate to do so because I felt that we had endured that too long. The more we gave in, the more we complied with that kind of treatment, the more oppressive it became.[32]

On the day of Parks’ trial — December 5, 1955 — the WPC distributed the 35,000 leaflets. The handbill read,

“We are…asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial … You can afford to stay out of school for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don’t ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off the buses Monday.”[33]

It rained that day, but the black community persevered in their boycott. Some rode in carpools, while others traveled in black-operated cabs that charged the same fare as the bus, 10 cents. Most of the remainder of the 40,000 black commuters walked, some as far as 20 miles (32 km).

That evening after the success of the one-day boycott, a group of 16 to 18 people gathered at the Mt. Zion AME Zion Church to discuss boycott strategies. At that time Parks was introduced but not asked to speak, despite a standing ovation and calls from the crowd for her to speak; when she asked if she should say something, the reply was, “Why, you’ve said enough.” [34]

The group agreed that a new organization was needed to lead the boycott effort if it were to continue. Rev. Ralph Abernathy suggested the name “Montgomery Improvement Association” (MIA).[35] The name was adopted, and the MIA was formed. Its members elected as their president Martin Luther King, Jr., a relative newcomer to Montgomery, who was a young and mostly unknown minister of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.[36]

That Monday night, 50 leaders of the African-American community gathered to discuss actions to respond to Parks’ arrest. Edgar Nixon, the president of the NAACP, said, “My God, look what segregation has put in my hands!”[37] Parks was considered the ideal plaintiff for a test case against city and state segregation laws, as she was seen as a responsible, mature woman with a good reputation. She was securely married and employed, was regarded as possessing a quiet and dignified demeanor, and was politically savvy. King said that Parks was regarded as “one of the finest citizens of Montgomery—not one of the finest Negro citizens, but one of the finest citizens of Montgomery.”[7]

Parks’ court case was being slowed down in appeals through the Alabama courts on their way to a Federal appeal and the process could have taken years.[38] Holding together a boycott for that length of time would have been a great strain. In the end, black residents of Montgomery continued the boycott for 381 days. Dozens of public buses stood idle for months, severely damaging the bus transit company’s finances, until the city repealed its law requiring segregation on public buses following the US Supreme Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle that it was unconstitutional. Parks was not included as a plaintiff in the Browder decision because the attorney Fred Gray concluded the courts would perceive they were attempting to circumvent her prosecution on her charges working their way through the Alabama state court system.[39]

Parks played an important part in raising international awareness of the plight of African Americans and the civil rights struggle. King wrote in his 1958 book Stride Toward Freedom that Parks’ arrest was the catalyst rather than the cause of the protest: “The cause lay deep in the record of similar injustices.”[40] He wrote, “Actually, no one can understand the action of Mrs. Parks unless he realizes that eventually the cup of endurance runs over, and the human personality cries out, ‘I can take it no longer.’”[41]

Detroit years 1960s

Parks on a Montgomery bus on December 21, 1956, the day Montgomery’s public transportation system was legally integrated. Behind Parks is Nicholas C. Chriss, a UPI reporter covering the event.

Parks on a Montgomery bus on December 21, 1956, the day Montgomery’s public transportation system was legally integrated. Behind Parks is Nicholas C. Chriss, a UPI reporter covering the event.

After her arrest, Parks became an icon of the Civil Rights Movement but suffered hardships as a result. Due to economic sanctions used against activists, she lost her job at the department store. Her husband quit his job after his boss forbade him to talk about his wife or the legal case. Parks traveled and spoke extensively about the issues.

In 1957, Raymond and Rosa Parks left Montgomery for Hampton, Virginia; mostly because she was unable to find work. She also disagreed with King and other leaders of Montgomery’s struggling civil rights movement about how to proceed, and was constantly receiving death threats.[42] In Hampton, she found a job as a hostess in an inn at Hampton Institute, a historically black college.

Later that year, at the urging of her brother and sister-in-law in Detroit, Sylvester and Daisy McCauley, Rosa and Raymond Parks, and her mother moved north to join them. The City of Detroit attempted to cultivate a progressive reputation, but Parks encountered numerous signs of discrimination against African-Americans. Schools were effectively segregated, and services in black neighborhoods substandard. In 1964, Mrs. Parks told an interviewer that, “I don’t feel a great deal of difference here…Housing segregation is just as bad, and it seems more noticeable in the larger cities.” She regularly participated in the movement for open and fair housing.[43]

Parks rendered crucial assistance in the first campaign for Congress by John Conyers. She persuaded Martin Luther King (who was generally reluctant to endorse local candidates) to appear with Conyers, thereby boosting the novice candidate’s profile.[43] When Conyers was elected, he hired her as a secretary and receptionist for his congressional office in Detroit. She held this position until she retired in 1988.[7] In a telephone interview with CNN on October 24, 2005, Conyers recalled, “You treated her with deference because she was so quiet, so serene — just a very special person … There was only one Rosa Parks.”[44] Doing much of the daily constituent work for Conyers, Parks often focused on socio-economic issues including welfare, education, job discrimination, and affordable housing. She visited schools, hospitals, senior citizen facilities, and other community meetings and kept Conyers grounded in community concerns and activism.[43]

Parks participated in activism nationally during the mid-1960s, traveling to support the Selma-to-Montgomery Marches, the Freedom Now Party,[45] and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. She also befriended Malcolm X, who she regarded as a personal hero.[46]

Like many Detroit blacks, Mrs. Parks remained particularly concerned about housing issues. She herself lived in a neighborhood, Virginia Park, which had been compromised by highway construction and so-called urban renewal. By 1962, these policies had destroyed 10,000 structures in Detroit, displacing 43,096 people, 70 percent of them African-American. Parks lived just a mile from the epicenter of the uprising that took place in Detroit in 1967, and she considered housing discrimination a major factor that provoked the insurrection.[43]

In the aftermath of the 1967 disorder, Mrs. Parks collaborated with members of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and the Republic of New Afrika in raising awareness of police abuse during the conflict. She served on a “people’s tribunal” investigating the killing of three young men in what was known as the Algiers Hotel Incident. She also helped form the Virginia Park district council to help rebuild the area. The council facilitated the building of the only black-owned shopping center in the country.[43] Parks took part in the black power movement, attending the Philadelphia Black Power conference, and the Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana. She also supported and visited the Black Panther school in Oakland.[47][48][49]

1970s

In the 1970s, Parks organized for the freedom of political prisoners in the United States, particularly cases involving issues of self-defense. She helped found the Joann Little Defense Committee, and also worked in support of Gary Tyler. Little soon became the first woman in United States history to be acquitted under the defense that she used deadly force to resist sexual assault.[50] Gary Tyler has not been freed, but before Parks’ death was recognized as a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.[51][52]

The 1970s were a decade of loss for Parks in her personal life. Her family was plagued with illness; she and her husband had suffered stomach ulcers for years and both required hospitalization. In spite of her fame and constant speaking engagements, Parks was not a wealthy woman. She donated most of the money from speaking to civil rights causes, and lived on her staff salary and her husband’s pension. Medical bills and time missed from work caused financial strain that required her to accept assistance from church groups and admirers.

Her husband died of throat cancer on August 19, 1977 and her brother, her only sibling, died of cancer that November. Her personal ordeals caused her to become removed from the civil rights movement. She learned from a newspaper of the death of Fannie Lou Hamer, once a close friend. Parks suffered two broken bones in a fall on an icy sidewalk, an injury which caused considerable and recurring pain. She decided to move with her mother into an apartment for senior citizens. There she nursed her mother Leona through the final stages of cancer and geriatric dementia until she died in 1979 at the age of 92.

Final years

In 1980, Parks—widowed and without immediate family—rededicated herself to civil rights and educational organizations. She co-founded the Rosa L. Parks Scholarship Foundation for college-bound high school seniors,[53][54] to which she donated most of her speaker fees. In February 1987 she co-founded, with Elaine Eason Steele, the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development, an institute that runs the “Pathways to Freedom” bus tours which introduce young people to important civil rights and Underground Railroad sites throughout the country. Though her health declined as she entered her seventies, Parks continued to make many appearances and devoted considerable energy to these causes.

In 1992, Parks published Rosa Parks: My Story, an autobiography aimed at younger readers, which recounts her life leading to her decision to keep her seat on the bus. A few years later, she published her memoir, titled Quiet Strength (1995), which focuses on her faith in her life. On August 30, 1994, Joseph Skipper, an African-American drug addict, entered her home and attacked the 81-year-old Parks in the course of a robbery. The incident sparked outrage throughout the United States. After his arrest, Skipper said that he had not known he was in Parks’ home but recognized her after entering. Skipper asked, “Hey, aren’t you Rosa Parks?” to which she replied, “Yes.” She handed him $3 when he demanded money, and an additional $50 when he demanded more. Before fleeing, Skipper struck Parks in the face.[55] Skipper was arrested and charged with various breaking and entering offenses against Parks and other neighborhood victims. He admitted guilt and, on August 8, 1995, was sentenced to eight to 15 years in prison.[56] Suffering anxiety upon returning to her small central Detroit house following the ordeal, Parks moved into Riverfront Towers, a secure high-rise apartment building where she lived for the rest of her life.

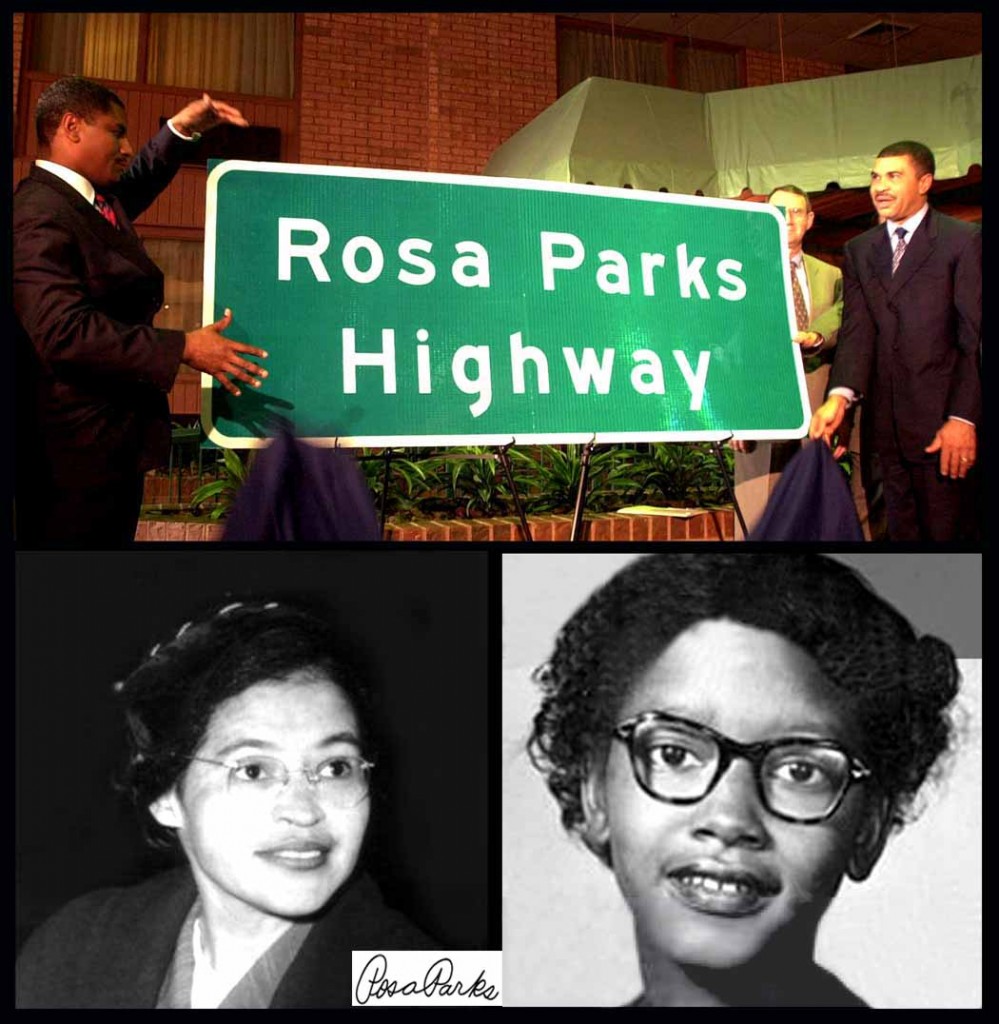

In 1994 the Ku Klux Klan applied to sponsor a portion of United States Interstate 55 in St. Louis County and Jefferson County, Missouri, near St. Louis, for cleanup (which allowed them to have signs stating that this section of highway was maintained by the organization). Since the state could not refuse the KKK’s sponsorship, the Missouri legislature voted to name the highway section the “Rosa Parks Highway”. When asked how she felt about this honor, she is reported to have commented, “It is always nice to be thought of.”[57][58]

In 1999 Parks filmed a cameo appearance for the television series Touched by an Angel. It was to be her last appearance on film; health problems made her increasingly an invalid.

In 2002 Parks received an eviction notice from her $1800 per month apartment due to non-payment of rent. Parks was incapable of managing her own financial affairs by this time due to age-related physical and mental decline. Her rent was paid from a collection taken by Hartford Memorial Baptist Church in Detroit. When her rent became delinquent and her impending eviction was highly publicized in 2004, executives of the ownership company announced they had forgiven the back rent and would allow Parks, by then 91 and in extremely poor health, to live rent free in the building for the remainder of her life.[59] Her heirs and various interest organizations alleged at the time that her financial affairs had been mismanaged.

For more information on “In popular culture” please visit the following link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosa_Parks

Death and funeral

Parks resided in Detroit until she died of natural causes at the age of 92 on October 24, 2005, in her apartment on the east side of the city. She and her husband never had children and she outlived her only sibling. She was survived by her sister-in-law, 13 nieces and nephews and their families, and several cousins, most of them residents of Michigan or Alabama.

City officials in Montgomery and Detroit announced on October 27, 2005, that the front seats of their city buses would be reserved with black ribbons in honor of Parks until her funeral. Parks’ coffin was flown to Montgomery and taken in a horse-drawn hearse to the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, where she lay in repose at the altar on October 29, 2005, dressed in the uniform of a church deaconess. A memorial service was held there the following morning. One of the speakers, United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, said that if it had not been for Parks, she would probably have never become the Secretary of State. In the evening the casket was transported to Washington, D.C. and transported by a bus similar to the one in which she made her protest, to lie in honor in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

Since the founding in 1852 of the practice of lying in state in the rotunda, Parks was the 31st person, the first American who had not been a U.S. government official, and the second private person (after the French planner Pierre L’Enfant) to be honored in this way. She was the first woman and the second black person to lie in state in the Capitol.[64][65] An estimated 50,000 people viewed the casket there, and the event was broadcast on television on October 31, 2005. A memorial service was held that afternoon at Metropolitan AME Church in Washington, DC.[66]

With her body and casket returned to Detroit, for two days, Parks lay in repose at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. Her funeral service was seven hours long and was held on November 2, 2005, at the Greater Grace Temple Church in Detroit. After the service, an honor guard from the Michigan National Guard laid the U.S. flag over the casket and carried it to a horse-drawn hearse, which was intended to carry it, in daylight, to the cemetery. As the hearse passed the thousands of people who were viewing the procession, many clapped and cheered loudly and released white balloons. Parks was interred between her husband and mother at Detroit’s Woodlawn Cemetery in the chapel’s mausoleum. The chapel was renamed the Rosa L. Parks Freedom Chapel in her honor.[67] Parks had previously prepared and placed a headstone on the selected location with the inscription “Rosa L. Parks, wife, 1913–.”

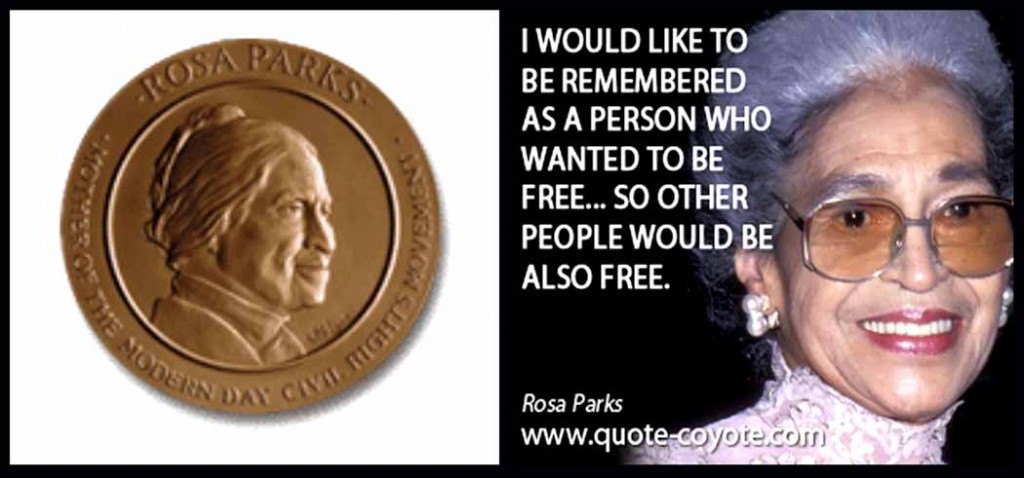

Left: The Rosa Parks Congressional Gold Medal

Left: Rosa Parks received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, awarded by President Bill Clinton in 1996 and the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999.

Left: Rosa Parks received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, awarded by President Bill Clinton in 1996 and the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999.

Right: Rosa Parks and Vice President Al Gore

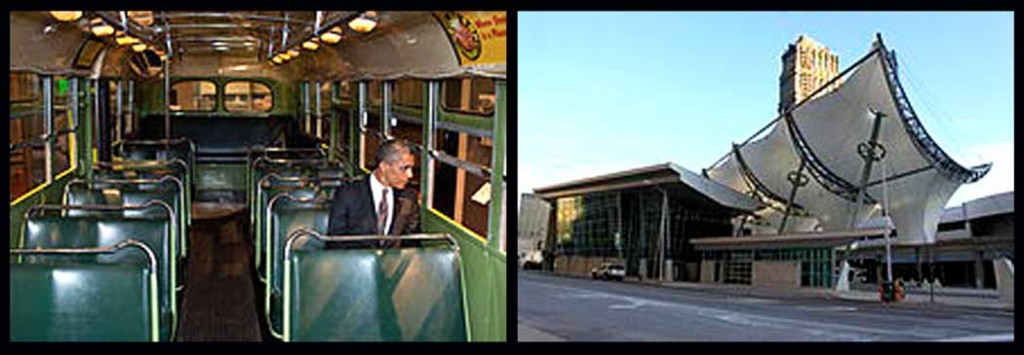

Left: Barack Obama sitting on the bus. Parks was arrested sitting in the same row Obama is in, but on the opposite side.

Right: Rosa Parks Transit Center, Detroit

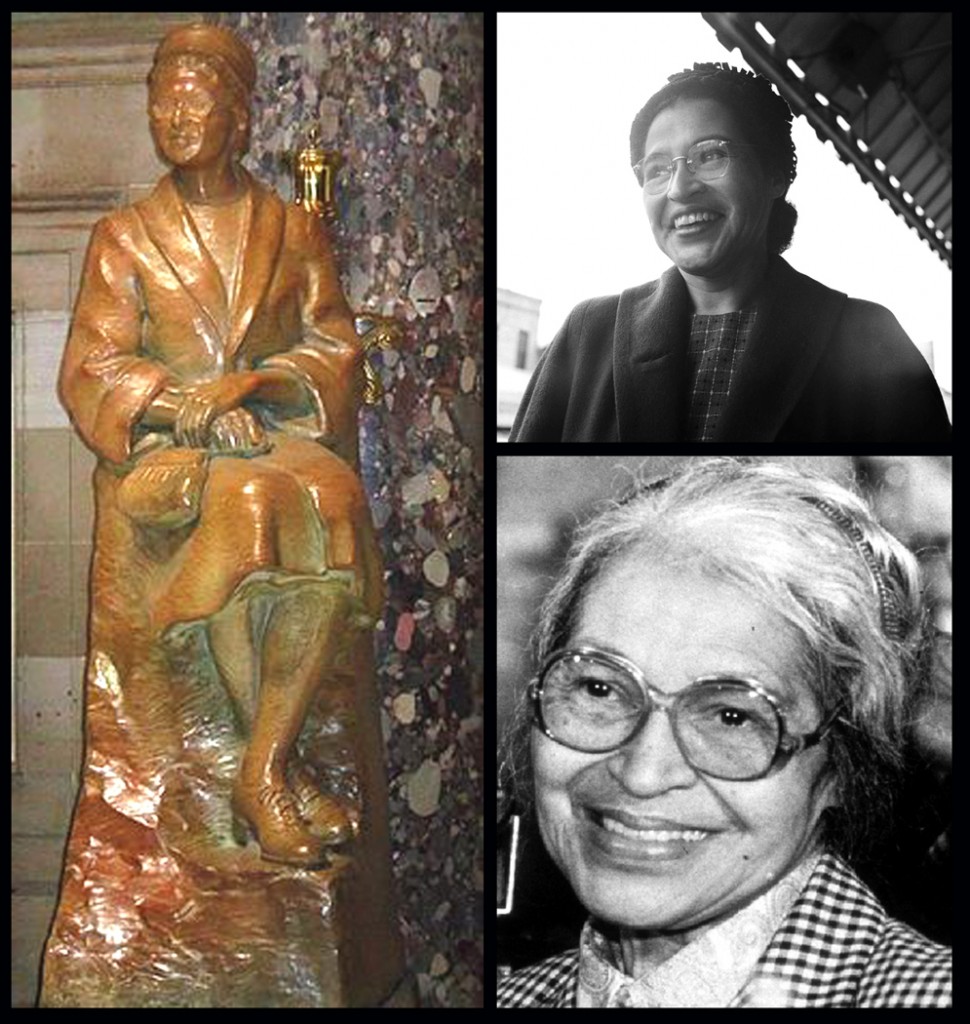

Left: Statue of Rosa Parks in Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol, Washington, D.C.

Left: Statue of Rosa Parks in Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol, Washington, D.C.

- 1976, Detroit renamed 12th Street “Rosa Parks Boulevard.”[68]

- 1979, the NAACP awarded Parks the Spingarn Medal,[69] its highest honor,[70]

- 1980, she received the Martin Luther King Jr. Award.[71]

- 1983, she was inducted into Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame for her achievements in civil rights.[72]

- 1990,

- Parks was invited to be part of the group welcoming Nelson Mandela upon his release from prison in South Africa.[73]

- Parks was in attendance as part of Interstate 475 outside of Toledo, Ohio is named after Parks.[74]

- 1992, she received the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Award along with Benjamin Spock and others at the Kennedy Library and Museum in Boston, Massachusetts.

- 1995, she received the Academy of Achievement’s Golden Plate Award in Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1996, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor given by the U.S. executive branch.

- 1998, she was the first to receive the International Freedom Conductor Award given by the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center.

- 1999,

- she received the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest award given by the U.S. legislative branch, the medal bears the legend “Mother of the Modern Day Civil Rights Movement”

- she receives the Windsor–Detroit International Freedom Festival Freedom Award.

- Time magazine named Parks one of the 20 most influential and iconic figures of the 20th century.[33]

- President Bill Clinton honored her in his State of the Union address, saying, “She’s sitting down with the first lady tonight, and she may get up or not as she chooses.”[75]

- 2000,

- her home state awarded her the Alabama Academy of Honor,[76]

- she receives the first Governor’s Medal of Honor for Extraordinary Courage.[77]

- She was awarded two dozen honorary doctorates from universities worldwide

- She is made an honorary member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority.

- the Rosa Parks Library and Museum on the campus of Troy University in Montgomery was dedicated to her.

- 2002,

- scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Parks on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[78]

- A portion of the Interstate 10 freeway in Los Angeles is named in her honor.

- 2003, Bus No. 2857 on which Parks was riding is restored and placed on display in The Henry Ford[79]

- 2004, In the Los Angeles County MetroRail system, the Imperial Highway/Wilmington station, where the Blue Line connects with the Green Line, has been officially named the “Rosa Parks Station”.[80][81]

- 2005,

- On October 30, 2005 President George W. Bush issued a proclamation ordering that all flags on U.S. public areas both within the country and abroad be flown at half-staff on the day of Parks’ funeral.

- Metro Transit in King County, Washington placed posters and stickers dedicating the first forward-facing seat of all its buses in Parks’ memory shortly after her death,[82][83]

- the American Public Transportation Association declared December 1, 2005, the 50th anniversary of her arrest, to be a “National Transit Tribute to Rosa Parks Day”.[84]

- On that anniversary, President George W. Bush signed Pub.L. 109–116, directing that a statue of Parks be placed in the United States Capitol’s National Statuary Hall. In signing the resolution directing the Joint Commission on the Library to do so, the President stated:

By placing her statue in the heart of the nation’s Capitol, we commemorate her work for a more perfect union, and we commit ourselves to continue to struggle for justice for every American.[85]

- Portion of Interstate 96 in Detroit was renamed by the state legislature as the Rosa Parks Memorial Highway in December 2005.[86]

- 2006,

- At Super Bowl XL, played at Detroit’s Ford Field, long-time Detroit residents Coretta Scott King and Parks were remembered and honored by a moment of silence. The Super Bowl was dedicated to their memory.[87] Parks’ nieces and nephews and Martin Luther King III joined the coin toss ceremonies, standing alongside former University of Michigan star Tom Brady who flipped the coin.

- On February 14, Nassau County, New York Executive, Thomas Suozzi announced that the Hempstead Transit Center would be renamed the Rosa Parks Hempstead Transit Center in her honor.

- 2007, Nashville, Tennessee, renamed MetroCenter Boulevard (8th Avenue North) (US 41A and SR 12) in September 2007 as Rosa L. Parks Boulevard.[88]

- 2009, On July 14, 2009, the Rosa Parks Transit Center opened in Detroit at the corner of Michigan and Cass Avenues.[89]

- 2010, In Grand Rapids, Michigan, a plaza in the heart of the city is named Rosa Parks Circle.

- 2012, President Barack Obama visited the famous Rosa Parks bus at the Henry Ford Museum after an event in Dearborn, Michigan, April 18, 2012.

- 2012, A street in West Valley City, Utah‘s second largest city, leading to the Utah Cultural Celebration Center is renamed Rosa Parks Drive.[90]

- 2013,

- On February 1, President Barack Obama proclaimed February 4, 2013, as the “100th Anniversary of the Birth of Rosa Parks.” He called “upon all Americans to observe this day with appropriate service, community, and education programs to honor Rosa Parks’s enduring legacy.”[91]

- On February 4, to celebrate Rosa Parks’ 100th birthday, the Henry Ford Museum declared the day a “National Day of Courage” with 12 hours of virtual and on-site activities featuring nationally recognized speakers, musical and dramatic interpretative performances, a panel presentation of Rosa’s Story and a reading of the tale Quiet Strength. The actual bus on which Rosa Parks sat was made available for the public to board and sit in the seat that Rosa Parks refused to give up.[92]

- On February 4, 2,000 birthday wishes gathered from people throughout the United States were transformed into 200 graphics messages at a celebration held on her 100th Birthday at the Davis Theater for the Performing Arts in Montgomery, Alabama. This was the 100th Birthday Wishes Project managed by the Rosa Parks Museum at Troy University and the Mobile Studio and was also a declared event by the Senate.[92]

- During both events the USPS unveiled a postage stamp in her honor.[93]

- On February 27, Parks became the first African American woman to have her likeness depicted in National Statuary Hall. The monument, created by sculptor Eugene Daub, is a part of the Capitol Art Collection among nine other females featured in the National Statuary Hall Collection.[94]

- 2015, the papers of Rosa Parks were cataloged into the Library of Congress, after years of a legal battle. [95]

Selma to Montgomery March

Selma to Montgomery March

From theNational Voting Rights Museum and Institute — The Alabama Voting Rights Project (AVRP), centered on Selma, Alabama and Dallas County, was a major campaign to secure effective federal protection of voting rights. That protection had been compromised out of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Three of Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC) main organizers-Director of Direct Action and Nonviolent Education James Bevel, Diane Nash, and James Orange had been working with AVRP since late 1963.

From theNational Voting Rights Museum and Institute — The Alabama Voting Rights Project (AVRP), centered on Selma, Alabama and Dallas County, was a major campaign to secure effective federal protection of voting rights. That protection had been compromised out of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Three of Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC) main organizers-Director of Direct Action and Nonviolent Education James Bevel, Diane Nash, and James Orange had been working with AVRP since late 1963.

In 1963, the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) and organizers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) began voter registration work. When white resistance to African American voter registration proved intractable, the DCVL requested the assistance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), who brought many prominent civil rights and civic leaders to support voting rights.

On February 18, 1965, an Alabama State Trooper, Corporal James Bonard Fowler, shot Jimmie Lee Jackson at point –blank range, as he tried to protect his mother and grandfather in a café to which they had fled while being attacked by troopers during a nighttime civil rights demonstration in Marion, the county seat of Perry County. Jackson died eight days later, of an infection resulting from the gunshot wound, at Selma’s Good Samaritan. His murder was the catalyst for the movement, the Selma to Montgomery March.

On February 18, 1965, an Alabama State Trooper, Corporal James Bonard Fowler, shot Jimmie Lee Jackson at point –blank range, as he tried to protect his mother and grandfather in a café to which they had fled while being attacked by troopers during a nighttime civil rights demonstration in Marion, the county seat of Perry County. Jackson died eight days later, of an infection resulting from the gunshot wound, at Selma’s Good Samaritan. His murder was the catalyst for the movement, the Selma to Montgomery March.

In response, James Bevel called for a march from Selma to Montgomery. At a memorial service for Jackson on Sunday, February 1965, Rev. James Bevel floated his idea at the end of a fiery sermon. His text was from the Book of Esther, where Esther is charged to “go unto the king, to make supplication unto him, and to make request before him for her people.” ”I must go to see the king!” Bevel shouted, “We must go to Montgomery and see the king!” Several days later Martin Luther King, Jr. confirmed that, a march from Selma to Montgomery would take place. He met with President Lyndon B. Johnson in Washington D. C., on March 5, outlining is views on the proposed voting rights legislation.

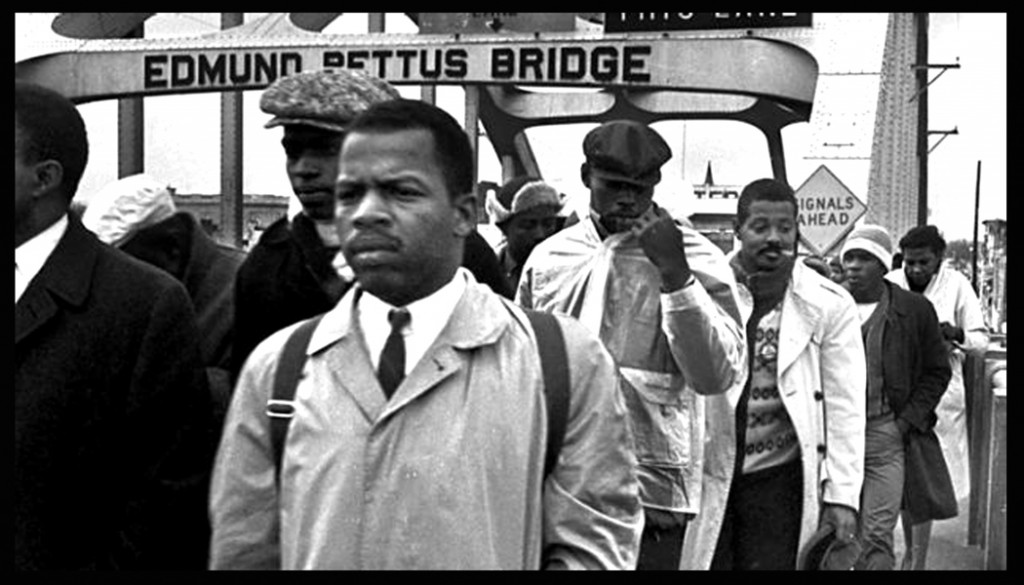

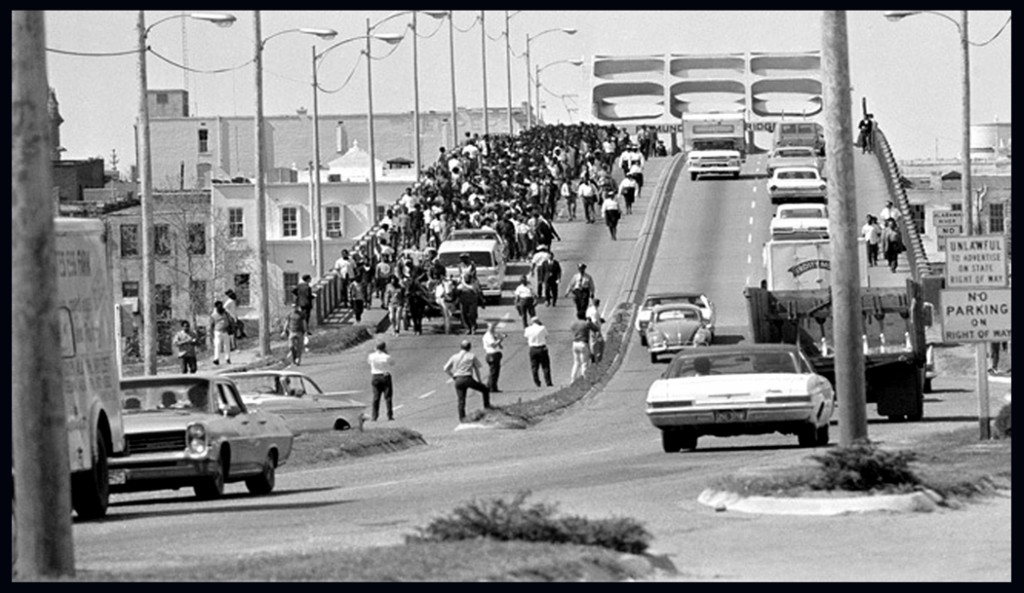

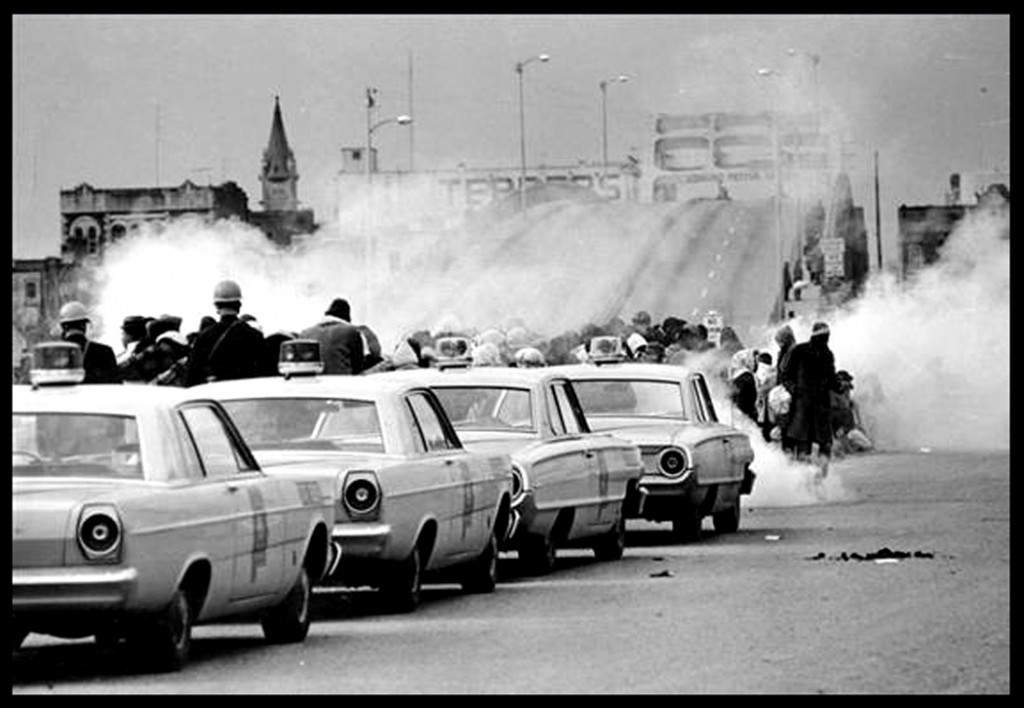

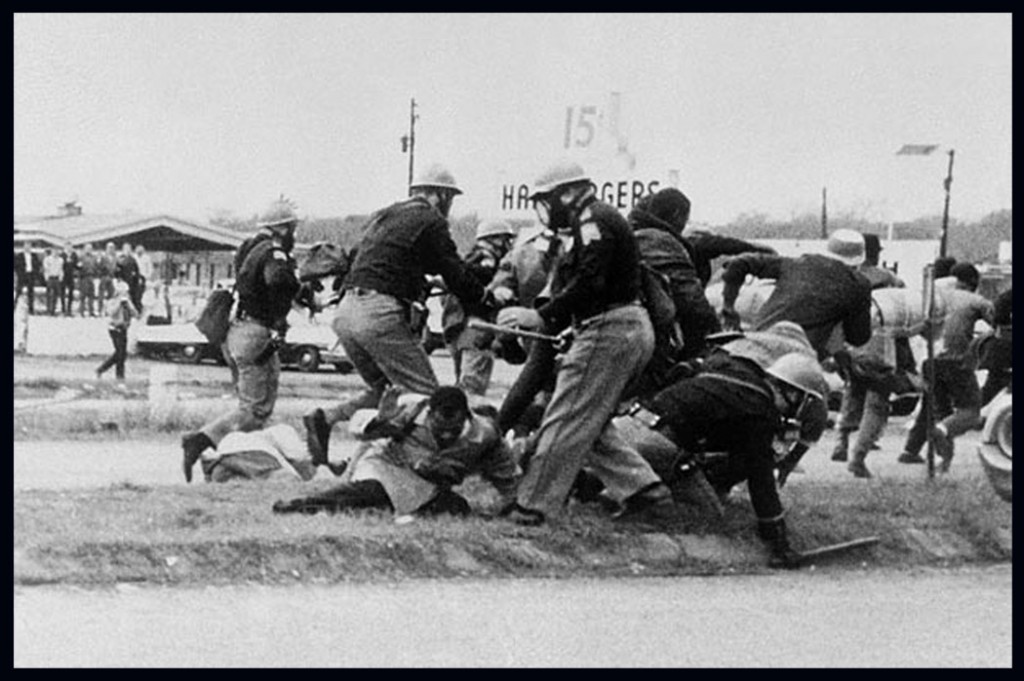

The Selma to Montgomery March consisted of three different marches in 1965 that marked the political and emotional peak of the American Civil Rights Movement. These three marches grew out of the voting rights movement in Selma, Alabama, launched by local African Americans who formed the Dallas County Voters League. The first march took place on Sunday, March 7, when 600 civil rights marchers, assembled on Brown Chapel. The mood was somber. This day became known as “Bloody Sunday”-when the civil rights marchers were attacked by state and local police with billy clubs and tear gas. The second march took place on March 9; it was know as “Turn Around Tuesday.” Only the third march, which began on March 21 and lasted five days, made it to Montgomery, 51 mile (82km) away.

The Selma to Montgomery March consisted of three different marches in 1965 that marked the political and emotional peak of the American Civil Rights Movement. These three marches grew out of the voting rights movement in Selma, Alabama, launched by local African Americans who formed the Dallas County Voters League. The first march took place on Sunday, March 7, when 600 civil rights marchers, assembled on Brown Chapel. The mood was somber. This day became known as “Bloody Sunday”-when the civil rights marchers were attacked by state and local police with billy clubs and tear gas. The second march took place on March 9; it was know as “Turn Around Tuesday.” Only the third march, which began on March 21 and lasted five days, made it to Montgomery, 51 mile (82km) away.

The marchers averaged 10 miles (16km) a day along U.S. Route 80, known in Alabama today as “Jefferson Davis Highway.” Protected by 2, 000 soldiers of the U.S. Army, 1,900 members of the Alabama National Guard under Federal command, and many FBI agents and Federal Marshals, they arrived in Montgomery on March 24, and at the Alabama Capital building on March 25, 1965.

National and international attention of the march highlighted the struggle, the adversity, the violence as well as the determination of the Selma protestors. As a result of the media coverage worldwide, Congress rushed to enact legislation that would guarantee voting rights for all Americans. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law on August 6, 1965.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., James Bevel and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), in partial collaboration with Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), attempted to organize a march from Selma, Alabama to the state capital of Montgomery on March 7, 1965. The first attempt to march on March 7 was aborted because of mob and police violence against the demonstrators. This day has since become known as “Bloody Sunday”. “Bloody Sunday” was a major turning point in the effort to gain public support for the Civil Rights Movement, the clearest demonstration up to that time of the dramatic potential of King’s nonviolence strategy. King, however, was not present. After meeting with President Lyndon B. Johnson, he decided not to endorse the march, but it was carried out against his wishes and without his presence on March 7 by the director of the Selma Movement, James Bevel, and by local Civil Rights Leaders. King’s next attempt to organize a march was set for March 9, it was known as “Turn Around Tuesday.” The SCLC petitioned for an injunction in Federal Court against the State of Alabama; this injunction was denied and the judge issued an order blocking the march until after a prayer session, before turning the marchers around and asking them to disperse so as not to violate the court order. The unexpected ending of this second march aroused the surprise and anger of many within the local movement. The march finally went ahead fully on March 25, 1965. At the conclusion of the march and on the steps of the state capitol, King delivered a speech that has become known as “How Long, not Long”. (source: National Voting Rights Museum and Institute)

Thursday, January 15, 2015

Posted by Ron at 7:42 AM 4 comments: Links to this post

Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to FacebookShare to Pinterest

Bridge to Freedom, 1965: Selma, Alabama  Eyes On The Prize Transcript: Bridge To Freedom (1965)

Eyes On The Prize Transcript: Bridge To Freedom (1965)

NARRATOR: Selma, Alabama, 1965.

C. T. VIVIAN: I don’t want to … (inaudible) leave. We have come to register to vote.

RACHEL WEST NELSON: If we can’t vote, you ain’t free. If you ain’t free, well then you’re slaves.

C. T. VIVIAN: We’re willing to be beaten for democracy.

NARRATOR: Years of struggle came down to this climactic battle for voting rights. Before it ended, black and white Americans gave their lives. But would that be enough?

C. T. VIVIAN: You people beat people bloody in order that they will not have the privilege to vote.

MALCOLM X: In the areas of the country where the government has proven itself unable or unwilling to defend the Negroes when they are being brutally and unjustly attacked, then the Negroes themselves should take whatever steps necessary to defend themselves.

NARRATOR: To many Americans, black and white, this was their worst nightmare. Race riots in northern cities during the summer of 1964. The civil rights movement was ten years old, nonviolence had been the strategy. But could nonviolence work in a society which grew angrier each day?

GUNNAR JAHN: On behalf of the Nobel Committee —

NARRATOR: To the world, Martin Luther King, Jr., had come to symbolize the success of nonviolent strategy. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in December, 1964.

GUNNAR JAHN: — and the gold medal.

NARRATOR: But in America, young militants were beginning to challenge King’s leadership. Dallas County, Selma, Alabama. For more than a year, organizers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC, had worked with local residents in waging a voter registration campaign. They met some resistance.

By the end of 1964, SNCC was exhausted, with little money to continue. Selma’s black leaders turned to Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for help.

MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR: Today marks the beginning of a determined, organized, mobilized campaign.

NARRATOR: King’s presence reopened an old rivalry between the ministers of SCLC and the young organizers of SNCC.

JAMES FORMAN: We felt that there should be a projection and an organization of indigenous leadership and leadership from the community. Whereas the Southern Christian Leadership Conference took the position that Martin was a charismatic leader who was mainly responsible for raising money and they raised most money off of his leadership. But this differences in leadership then led to differences in style of work. We wanted a movement that would survive the loss of our lives; therefore, the necessity to build a broad based movement and not just a charismatic leader.

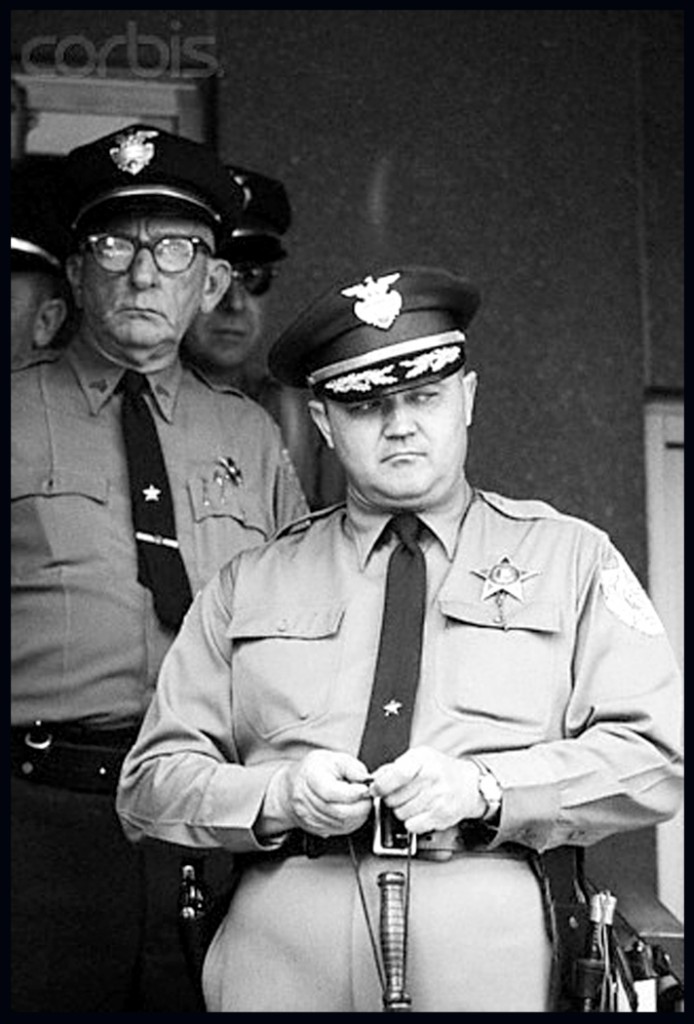

NARRATOR: SNCC and SCLC put aside their differences and launched a combined effort on January 18th, 1965. The Dallas County courthouse steps became a dramatic stage as prospective voters lined up for the registrar’s office in Selma. The key actor was Sheriff Jim Clark. Movement leaders counted on Clark to draw media attention, the kind of attention that would interest Washington and win voting rights legislation.

MAYOR SMITHERMAN: I am a segregationist. I do not believe in biracial committees.

MAYOR SMITHERMAN: I am a segregationist. I do not believe in biracial committees.

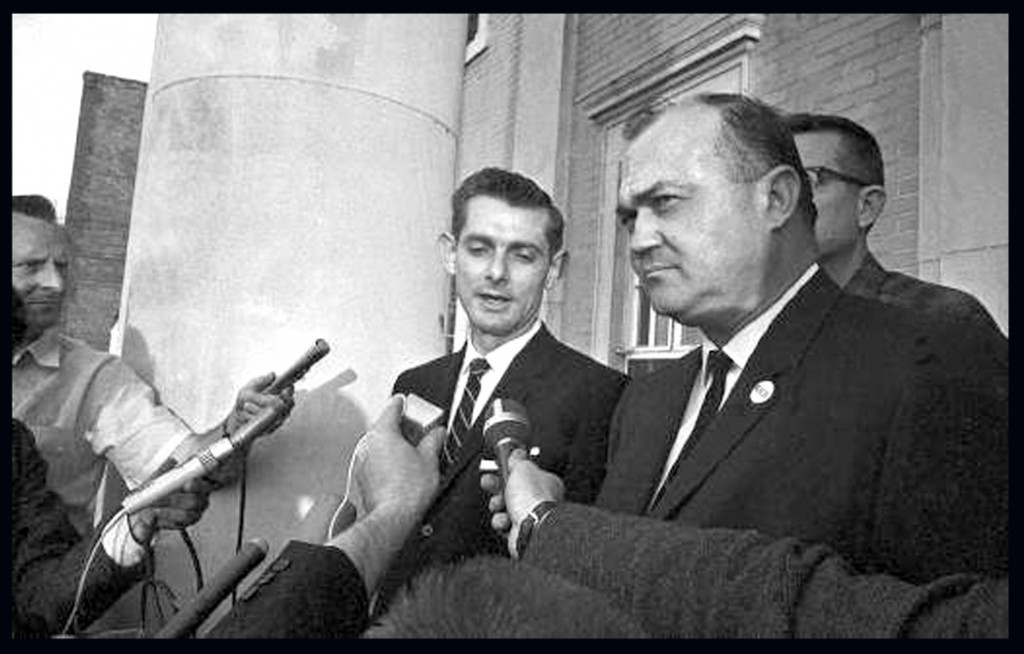

NARRATOR: Selma’s political leaders understood the movement’s tactics and were desperate not to get caught in the middle. Mayor Joseph Smitherman and his public safety director, Wilson Baker, hoped to restrain the volatile Sheriff Clark as he dealt with the demonstrators.

JOSEPH SMITHERMAN: They picked Selma just like a movie producer would pick a set. You had the right ingredients. I mean, you’d had to have seen Clark in his day. He had a helmet on like General Patton, he had the clothes, the Eisenhower jacket and a swagger stick, and then Baker was very impressive and I guess I was the least of all. I was 145 pounds and a crew cut and big ears. So you had a young mayor with no background or experience.

MAYOR SMITHERMAN: Our city and our county has been subjected to the greatest pressures I think any community in the country has had to withstand. We’ve had in our area here outside agitation groups of all levels. We’ve had Martin Luther Coon — Pardon me, sir, Martin Luther King, we have had people of the Nazi Party, the States Rights Party, both of these groups have come in, they have continually harassed and agitated us for approximately three or four weeks.

NARRATOR: More than half of Dallas County’s citizens were black, but less than one percent were registered by 1965. Throughout much of the South, custom and law had long prevented blacks from registering. In Selma, the registrar’s office was open only two days a month. Registrars would arrive late, leave early, and take long lunch hours. Few blacks who lined up would get in. And getting in was no guarantee of being registered.

President Johnson knew the problem, and now having soundly defeated conservative Barry Goldwater in the recent election, he set this goal.

PRESIDENT LYNDON B. JOHNSON: I propose that we eliminate every remaining obstacle to the right and the opportunity to vote.

NARRATOR: But Johnson’s staff had doubts about pushing for more legislation.

NICHOLAS KATZENBACH: I think those of us who had been involved day in and day out in civil rights legislation, in getting the 1964 Civil Rights Act through Congress were the people who were dragging our feet and wanted breathing room. The President didn’t want that. He said, “Get it and get it now because we’ll never have a better opportunity to get legislation on any subject including civil rights than we have right now in 1965. We have the majority to do it, we can do it.”

NARRATOR: Although Sheriff Clark tried to control his temper, the strain began to show. In mid-January, he arrested Mrs. Amelia Boynton, a highly respected community leader. Angered by Mrs. Boynton’s arrest, 105 local teachers marched to the courthouse in protest, knowing they might be fired by the white school board.

SHERIFF CLARK: This court house is a serious place of business and you seem to think you can take it just to be, uh, Disneyland or something on parade. Do you have business in the court house?

TEACHER: We just, we just want to pass through.

SHERIFF CLARK: Do you have any business in the court house?

TEACHER: The only business we have is to come by the Board of Registrars to register…

SHERIFF CLARK: The Board of Registrars is not in session this afternoon as you were informed. You came down to make a mockery out of this court house and we’re not going to have it.

REV. FREDERICK D. REESE: So I saw then that he was not going to arrest us, as I really wanted him to do. Therefore, we asked the teachers then to regroup and we marched back, not to the school but to the Brown Chapel Church, at which time there was a rally held.

REV. FREDERICK D. REESE: So I saw then that he was not going to arrest us, as I really wanted him to do. Therefore, we asked the teachers then to regroup and we marched back, not to the school but to the Brown Chapel Church, at which time there was a rally held.

NARRATOR: The teachers march was the first black middle class demonstration in Selma. Sheyann Webb and Rachel West were schoolchildren at the time.

SHEYANN WEBB: And it was a amazing to see how many teachers had participated. I remember vividly on that day when I saw my teachers marching with me, you know, just for the right to vote.

RACHEL WEST NELSON: Teachers there was somewhat like up in the upper class, you know. People looked up to teachers then, they looked up to preachers. They were somewhat like leaders for back then.

REV. FREDERICK D. REESE: Then the undertakers got a group and they marched. The beauticians got a group, they marched. Everybody marched after the teachers marched because teachers had more influence than they ever dreamed in the community.

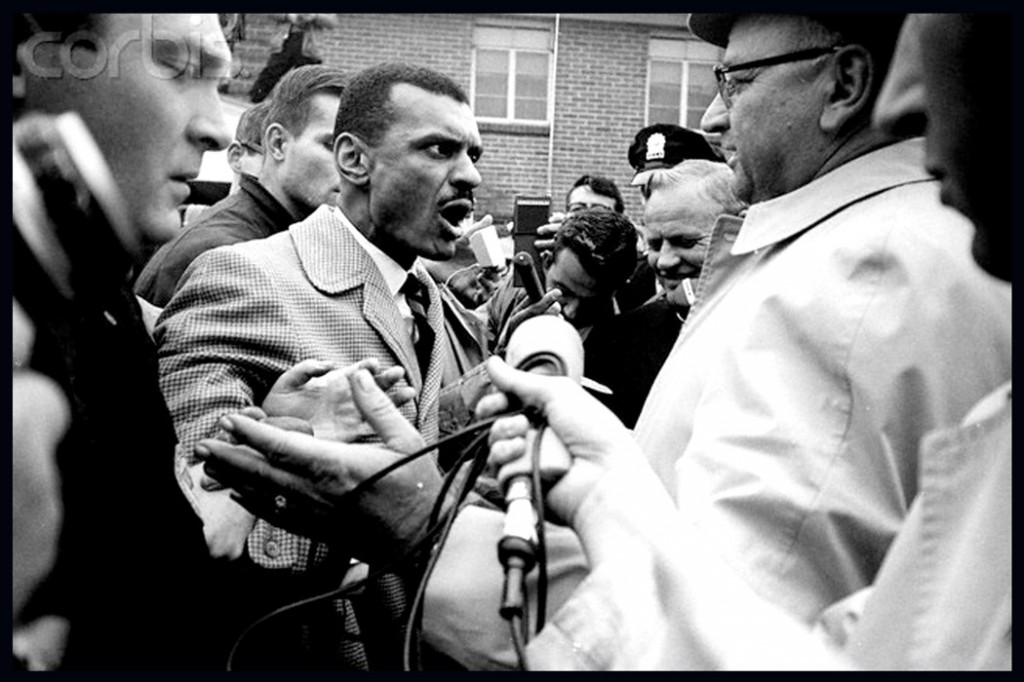

C. T. VIVIAN: And we want you to know, gentlemen, that every one of you, we know your badge numbers, we know your names.

NARRATOR: In mid-February, Reverend C. T. Vivian, an SCLC organizer, confronted Sheriff Clark and his deputies on the courthouse steps.  C.T. Vivian

C.T. Vivian

C. T. VIVIAN: But believe me, there were those that followed Hitler, like you blindly follow this Sheriff Clark who didn’t think their day was coming. But they also were pulled into courtrooms and they were also given their death sentences. You’re not this bad a racist, but you’re a racist in the same way Hitler was a racist. And you’re blindly following a man that’s leading you down a road that’s going to bring you into federal court. Now, I’m representing people in Dallas County and I have that right to do so. Now, and as I represent them and they can speak for themselves, is what I’m saying true? Is it what you think and what you believe? For this is not a local problem, gentlemen. This is a national problem. You can’t keep anyone in the United States from voting without hurting the rights of all other citizens. Democracy is built on this. This is why every man has the right to vote, regardless.

JIM CLARK: And he started shouting at me that I was a Hitler, I was a brute, I was a Nazi. I don’t remember everything he called me. And I did lose my temper then.

C. T. VIVIAN: We have come to be here because they are registering at this time.

SHERIFF CLARK: Turn that light out. You’re blinding me and I can’t enforce the law with the light in my face.

C. T. VIVIAN: We have come to register and this is our reason for being here. We’re not —

SHERIFF CLARK: You’re blinding me with that light. Move back.

C. T. VIVIAN: You can arrest us. You can arrest us, Sheriff Clark. You don’t have to beat us.

JIM CLARK: I don’t remember even hitting him, but I went to the doctor, got an x-ray and found out I had a linear fracture on my finger on my left hand.

C. T. VIVIAN: With Jim Clark, it was a clear engagement between the forces and movements and the forces of the structure that would destroy movement. It was a clear engagement between those who wished the fullness of their personalities to be met and those that would destroy us physically and psychologically. You do not walk away from that. This is what movement meant. Movement meant that finally we were encountering on a mass scale the evil that had been destroying us on a mass scale. You do not walk away from that, you continue to answer it.

C. T. VIVIAN: If we’re wrong, why don’t you arrest us?

POLICEMAN: Why don’t you get out of in front of the camera and go on. Go on.

C. T. VIVIAN: It’s not a matter of being in front of the camera. It’s a matter of facing your sheriff and facing your judge. We’re willing to be beaten for democracy, and you misuse democracy in this street. You beat people bloody in order that they will not have the privilege to vote. You beat me in the side and then hide your blows. We have come to register to vote.

MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR: I’m here to tell you tonight that the businessmen, the mayor of this city, the police commissioner of this city, and everybody in the white power structure of this city must take a responsibility for everything that Jim Clark does and has created. It’s time for us to say to these men that if you don’t do something about it, we will have no alternative but to engage in broader and more drastic forms of civil disobedience in order to bring the attention of a nation to this whole issue in Selma, Alabama. (Transcript: Eyes On The Prize, Bridge To Freedom, 1965)

Posted by Ron at 5:20 AM No comments: Links to this post

Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to FacebookShare to Pinterest

For more information on “In popular culture” please visit the following link https://usslave.blogspot.com/2015_01_01_archive.html

Friday, January 9, 2015

The Enduring Scars of Slavery

Anne Farrow: The Enduring Scars of Slavery

From the Hartford Courant, “Recognize Enduring Scars Of Slavery’s Shackles,” by Anne Farrow of Haddam (the author of “The Logbooks: Connecticut’s Slave Ships and Human Memory” and co-author of “Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery.”), on 19 December 2014

From the Hartford Courant, “Recognize Enduring Scars Of Slavery’s Shackles,” by Anne Farrow of Haddam (the author of “The Logbooks: Connecticut’s Slave Ships and Human Memory” and co-author of “Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery.”), on 19 December 2014

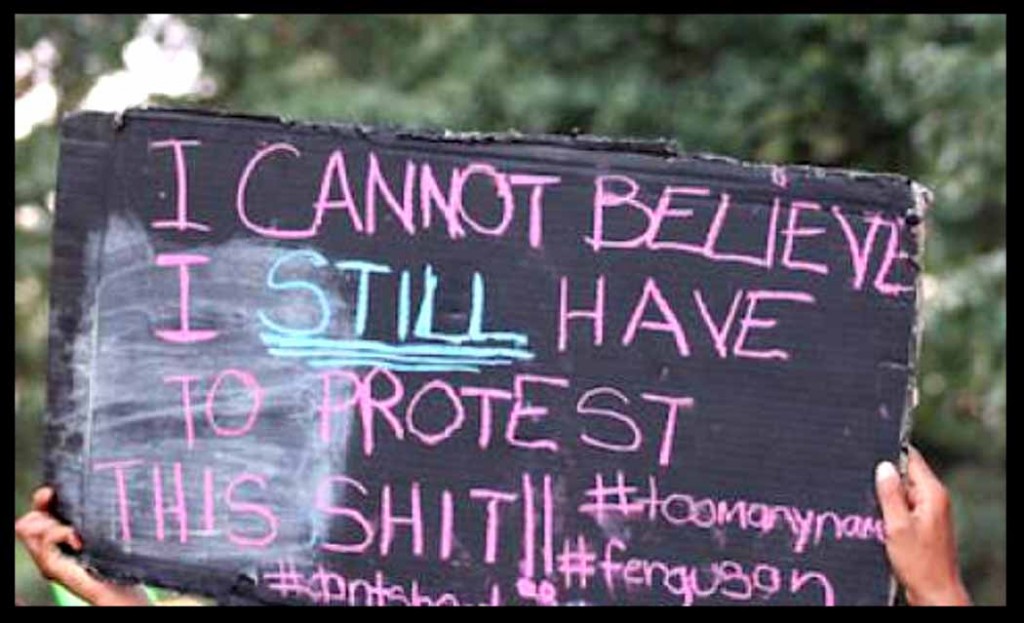

We may never know what happened between black teenager Michael Brown and white police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Mo., but if we knew our history with slavery, we would know all that we need to about what happened during their 90-second fatal encounter and its devastating aftermath.

I am 63 years old, a white woman and in the odd and probably fortunate position of having written a newly published book on America’s memory of slavery just at the moment when black anger over continuing racial injustice has captured national attention. Nine years ago, when I spoke about a book I co-wrote on connections to slavery in the antebellum North, anguished audiences asked: Why don’t we know about this?

I am 63 years old, a white woman and in the odd and probably fortunate position of having written a newly published book on America’s memory of slavery just at the moment when black anger over continuing racial injustice has captured national attention. Nine years ago, when I spoke about a book I co-wrote on connections to slavery in the antebellum North, anguished audiences asked: Why don’t we know about this?

Now, the questions are about Ferguson, and the gulf between the way white and black Americans view and experience our justice system. The questions are about rage. There is a continuum between the questions a decade ago and the ones I hear now.

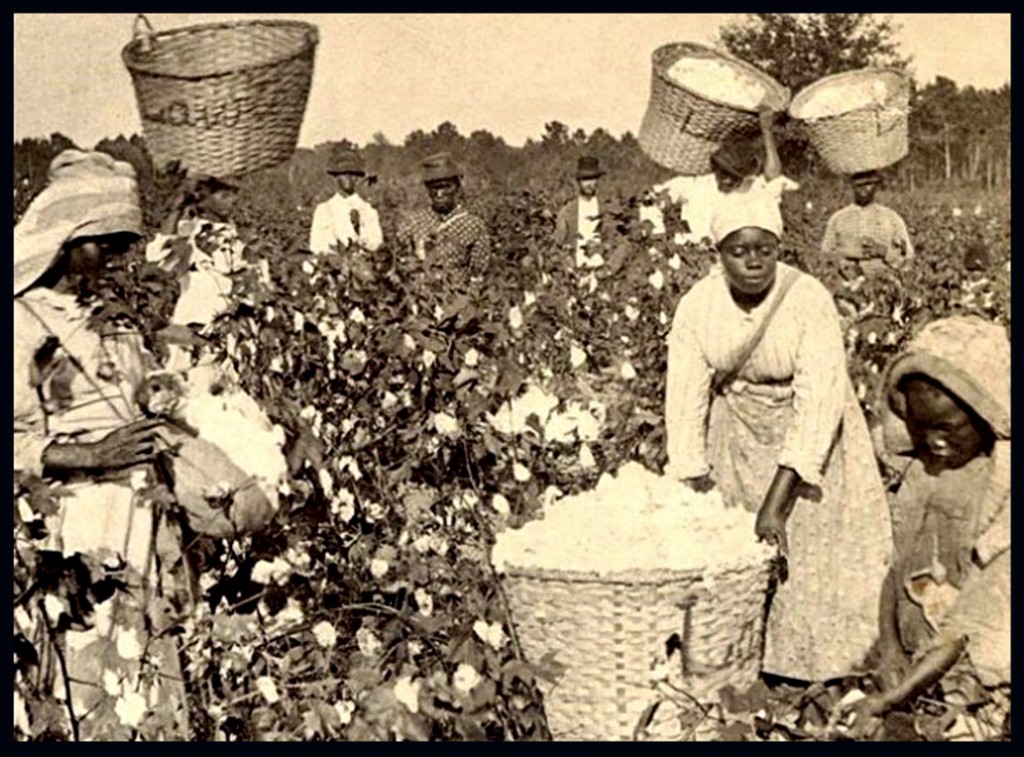

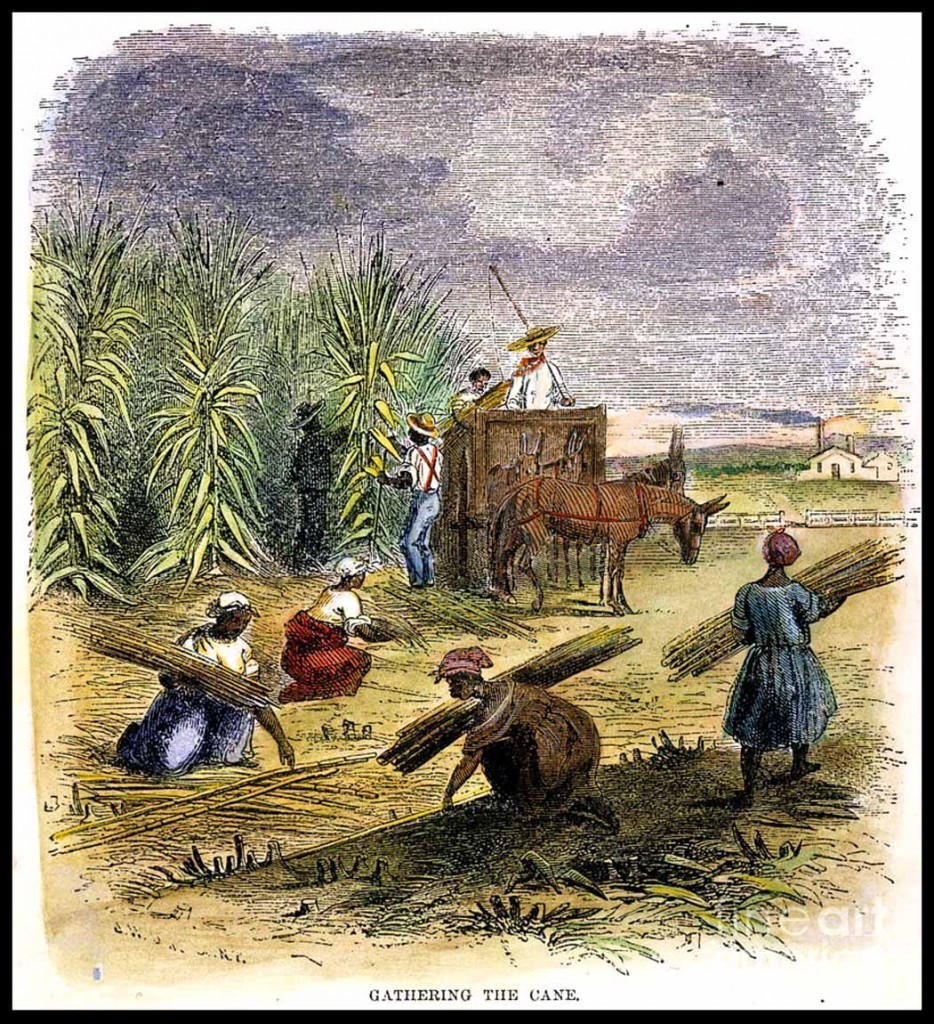

Slavery in America was not a footnote, not “the sad chapter” of our history but the cornerstone of our making. Three generations of eminent historians have documented the astonishing scope, duration, economic importance and savagery of bondage in America, but this key piece of our past still is not prominent in the narrative of our nation.

Slavery in America was not a footnote, not “the sad chapter” of our history but the cornerstone of our making. Three generations of eminent historians have documented the astonishing scope, duration, economic importance and savagery of bondage in America, but this key piece of our past still is not prominent in the narrative of our nation.

In studying a set of 18th-century ships’ logs linking Connecticut and the slave trade, I saw that when we made stolen black labor our national bedrock and created a system where inferiority was identifiable by color, we doomed ourselves to the present day and a nation where justice and parity for black people have not been achieved.

The Connecticut seamen and commanders in these ships’ logs did not regard their suffering African cargo as human. When they shoved them onto the English Caribbean islands, where the captives suffered and died in an agricultural system infamous for its cruelty, notions of kidnap and murder did not cross their minds. These black men, women and children were not seen as innocent people; they were a business opportunity, part of a supply-and-demand chain that separated an estimated 12.5 million Africans from their homes and changed a hemisphere.

The Connecticut seamen and commanders in these ships’ logs did not regard their suffering African cargo as human. When they shoved them onto the English Caribbean islands, where the captives suffered and died in an agricultural system infamous for its cruelty, notions of kidnap and murder did not cross their minds. These black men, women and children were not seen as innocent people; they were a business opportunity, part of a supply-and-demand chain that separated an estimated 12.5 million Africans from their homes and changed a hemisphere.

Several hundred thousand in that involuntary migration came to the American colonies, and their palpable humanity didn’t really pose a problem for most settlers here, either. The most pressing exigency of this brave new world was labor, and these valuable workers were the key to America’s early success. Their stolen, uncompensated labor gave us our running start.

The best and most educated people owned slaves, promulgated its benefits and enjoyed the wealth slavery created — the keeper of my Connecticut logbooks was not an obscure mariner but a Saltonstall and the scion of an aristocratic family. This comfort level with the omnipresence of human bondage became a cascading series of accepted and pathological untruths: Black people were designed for slavery; they didn’t mind being enslaved; they weren’t really human; and they didn’t recognize degradation and injustice.

The best and most educated people owned slaves, promulgated its benefits and enjoyed the wealth slavery created — the keeper of my Connecticut logbooks was not an obscure mariner but a Saltonstall and the scion of an aristocratic family. This comfort level with the omnipresence of human bondage became a cascading series of accepted and pathological untruths: Black people were designed for slavery; they didn’t mind being enslaved; they weren’t really human; and they didn’t recognize degradation and injustice.

Scholar Arna Alexander Bontemps documented the way captives in the South became invisible. Their labor was essential to their captors, but because they were not regarded as human beings, their emotions, their lives and their grief as exiles were not part of the record. They appeared as purchases, or as laborers. These one-name possessions appear in many Northern records as well.

By the time of the Civil War, 4 million black people were held in slavery in the U.S. The suffering of those millions — the majority of whom were born here — has never been adequately addressed and explored by Americans. The emancipation that ended legal slavery did not end racial prejudice, and those Americans who believe that it did need only look at the most recent statistics on African-American poverty, access to education, housing and health care. African-Americans are poorer than they were nine years ago.

Americans still do not have a shared and meaningful body of knowledge about a labor system that held those millions in bondage. The hard question of how a post-Enlightenment nation, founded on principles of personal liberty, became the largest holder of slaves in the Western world is still waiting to be answered.

Americans still do not have a shared and meaningful body of knowledge about a labor system that held those millions in bondage. The hard question of how a post-Enlightenment nation, founded on principles of personal liberty, became the largest holder of slaves in the Western world is still waiting to be answered.

If, as a country, we truly understood the extraordinary human catastrophe we created when we became economically dependent on the oppression of black people, if we took this in all its terrible dimensions into our hearts and then our history, we would not be scratching our heads over Ferguson. We would understand exactly why the legacy of enslavement is raging through our cities and begin to do something about it. (source: Hartford Courant OP Ed)