Ing’s Peace Poem Translated into Iranian

And

Iranian Artwork

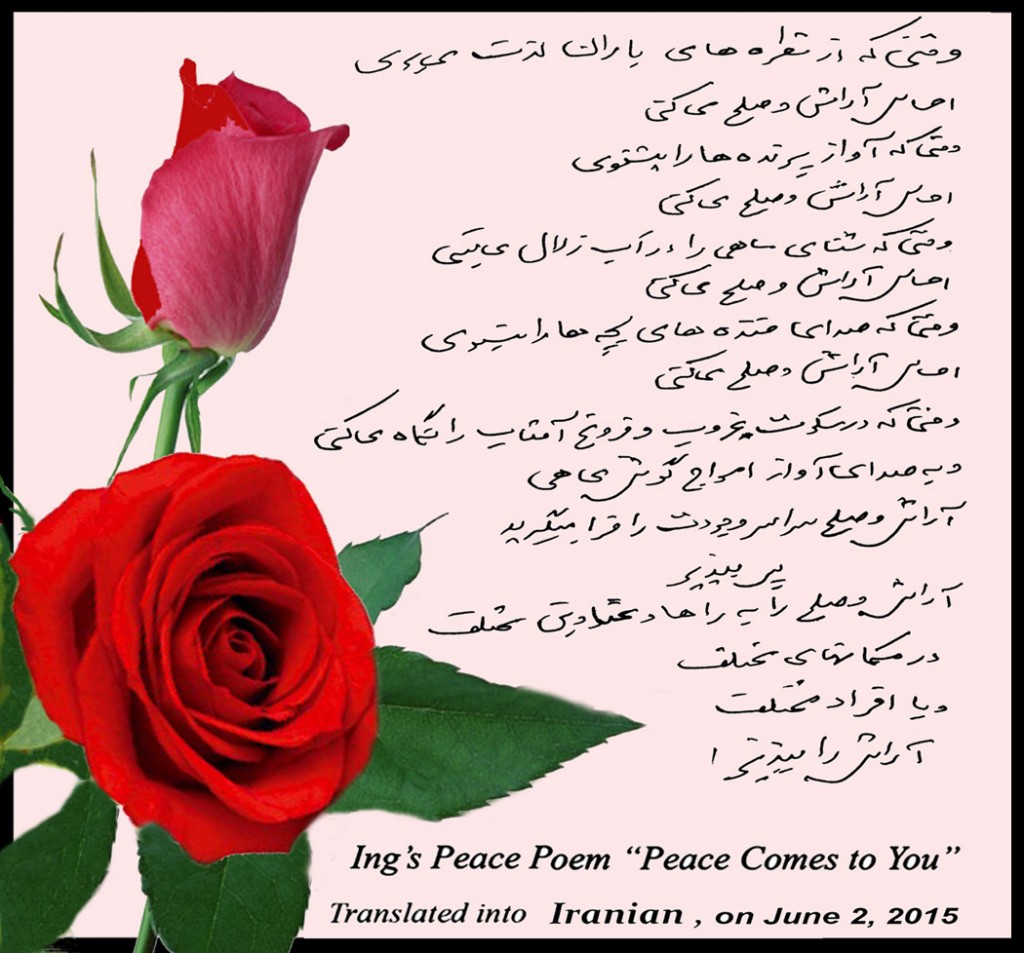

Ing’s Peace Poem “Peace Come to You”

Translated into Iranian on June 2nd, 2015

Last month an Iranian person was kind enough to translate my, Peace Come to You, poem into the Iranian language. It is a good occasion to celebrate the “Iran nuclear talk’s agreement”, for me to post the Iranian translation on my blog page. I love all kinds of artwork. I was glad that I had the opportunity to view the Iranian art that I posted on this project.

Red Rose (Rosa) is the National Flower of Iran, and Tulip also serves as the flower emblem for Iran.

Iranian Artwork

Culture: Culture of Iran and Persian mythology

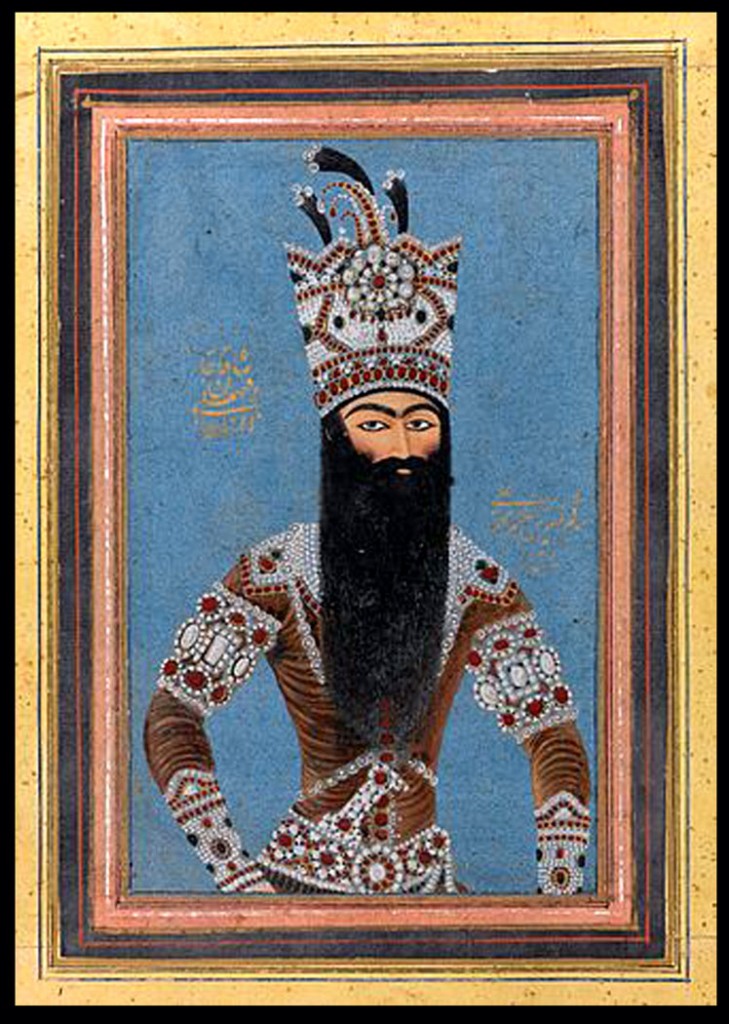

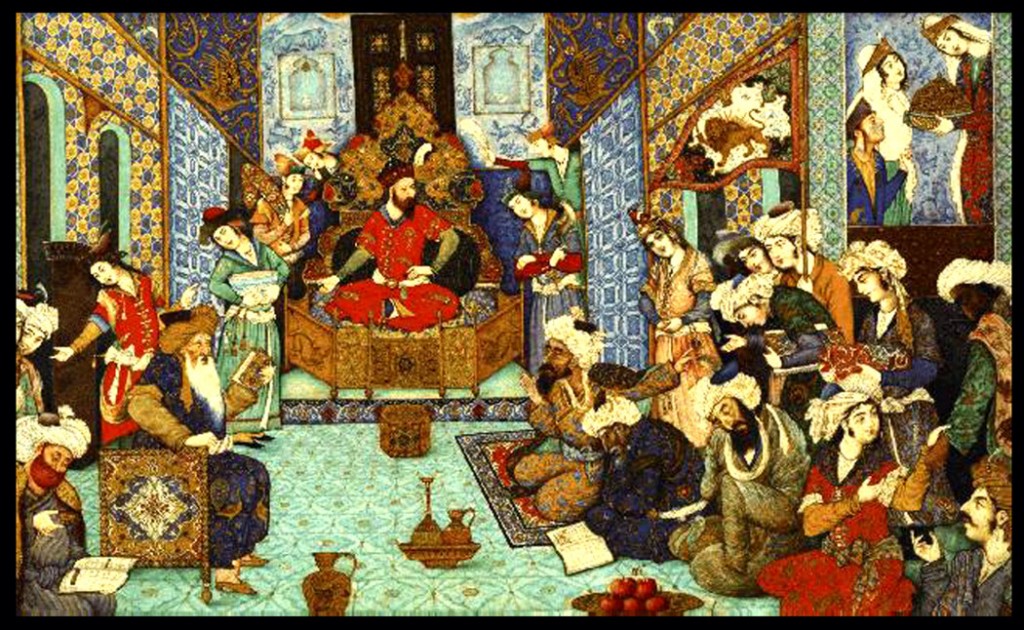

Safavid painting kept at the Shah Abbas Caravanserai in Isfahan

Safavid painting kept at the Shah Abbas Caravanserai in Isfahan

As the first sentence of Richard Nelson Frye‘s Greater Iran reads, “Iran’s prize possession has been its culture.”[283]

Persian culture has long been a predominant culture of the region, with Persian considered the language of intellectuals during much of the 2nd millennium, and the language of religion and the populace before that.[citation needed]

The Sassanid era was an important and influential historical period in Iran as Iranian culture influenced China, India and Roman civilization considerably,[284] and so influenced as far as Western Europe and Africa.[285]

This influence played a prominent role in the formation of both Asiatic and European medieval art.[286] This influence carried forward to the Islamic world. Much of what later became known as Islamic learning, such as philology, literature, jurisprudence, philosophy, medicine, architecture and the sciences were based on some of the practises taken from the Sassanid Persians.[287][288][289]

Art:Iranian art and Persian carpet

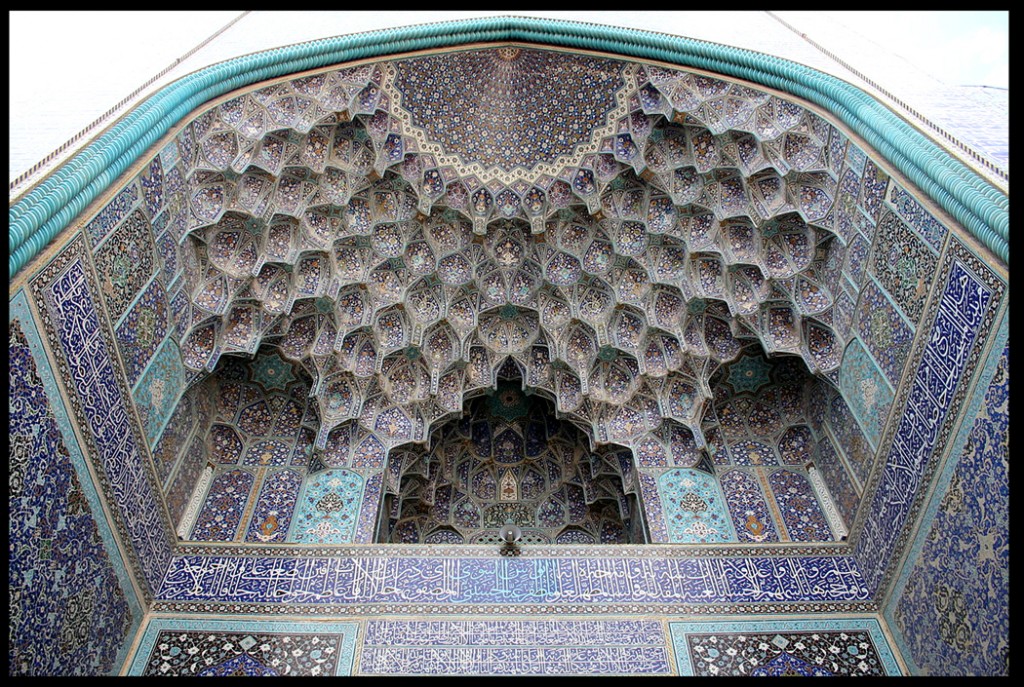

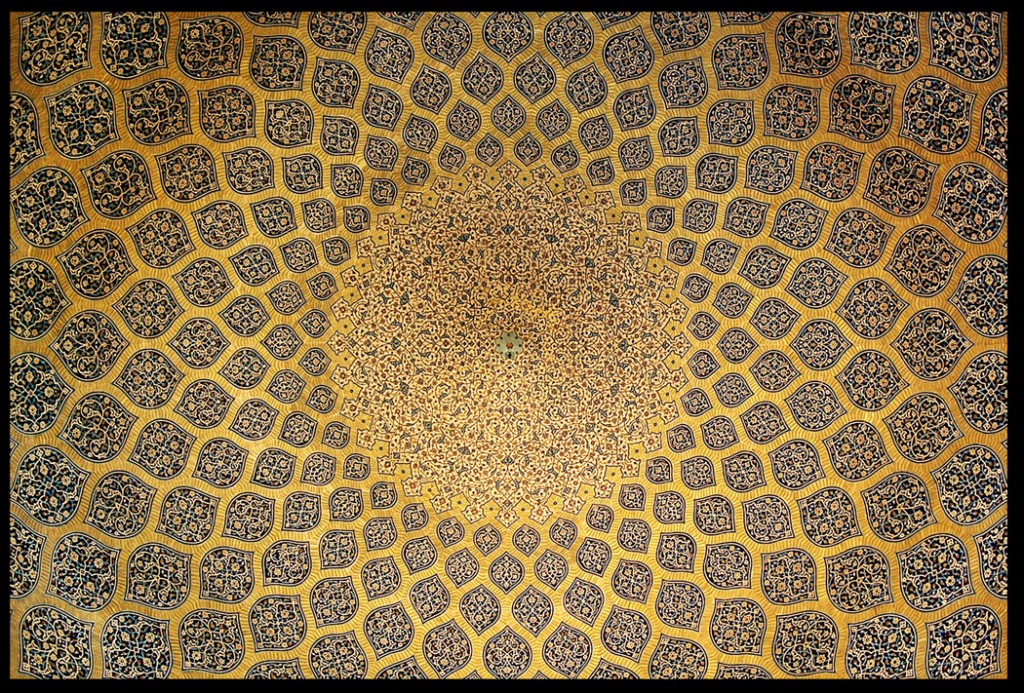

Ceiling of the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque in Isfahan

Iranian art has one of the richest art heritages in world history and encompasses many disciplines including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and stonemasonry. There is also a very vibrant Iranian modern and contemporary art scene. The modern art movement in Iran had its genesis in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The 1949 opening of the Apadana gallery in Tehran by Mahmoud Javadipour and other colleagues, and the emergence of artists like Marcos Grigorian in the 1950s, signaled a commitment to the creation of a form of modern art grounded in Iran.[290]

Carpet–weaving is undoubtedly one of the most distinguished manifestations of Persian culture and art, and dates back to ancient Persia and the Bronze Age. Iran is the world’s largest producer and exporter of handmade carpets, producing three quarters of the world’s total output and having a share of 30% of world’s export markets.[291][292]

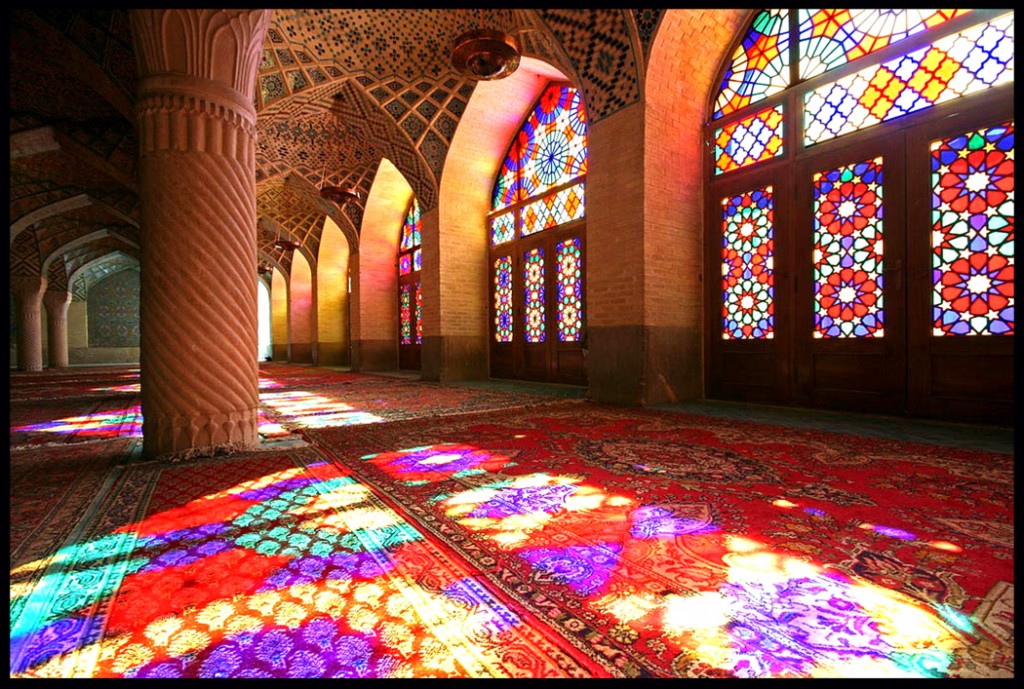

Architecture: Iranian architecture and Persian gardens

According to Persian historian and archaeologist Arthur Pope, the supreme Iranian art, in the proper meaning of the word, has always been its architecture. The supremacy of architecture applies to both pre-and post-Islamic periods.[293] The history of architecture of Iran goes back to the seventh millennium BC.

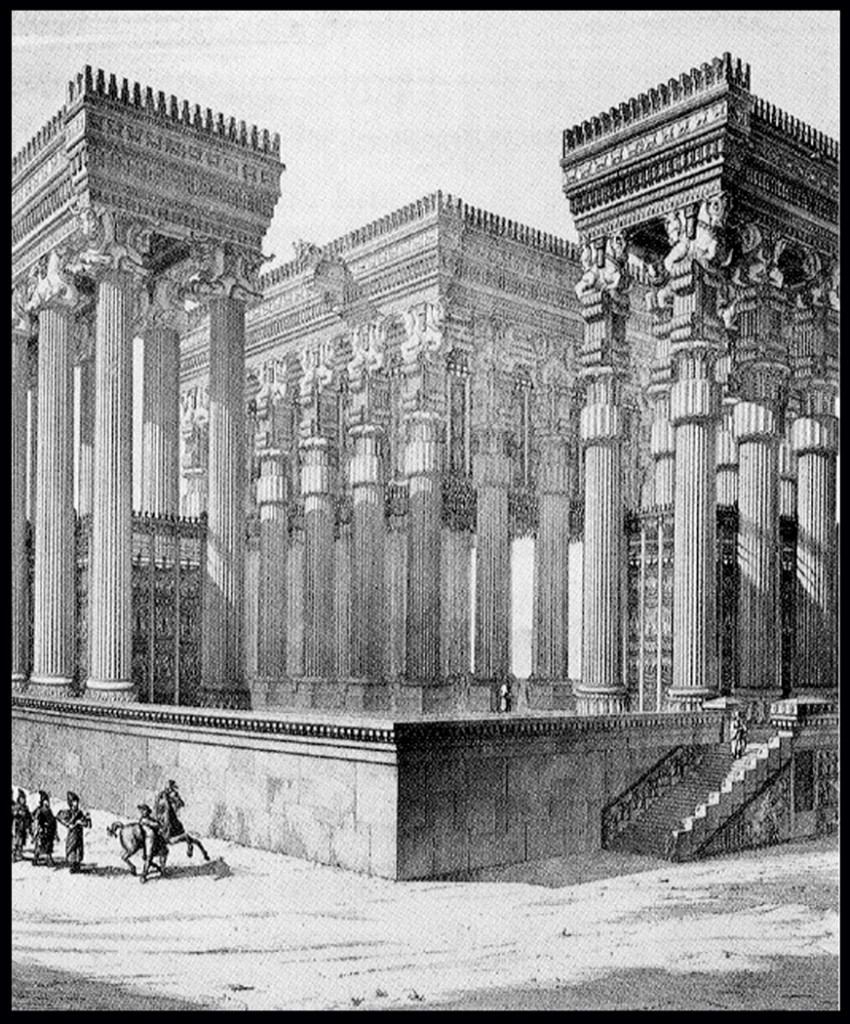

Iranian architecture generally displays great variety, both structural and aesthetic, developing gradually and coherently out of earlier traditions and experience. Without sudden innovations, and despite the repeated trauma of invasions and cultural shocks, it has achieved “an individuality distinct from that of other Muslim countries”.[294] Its paramount virtues are several: “a marked feeling for form and scale; structural inventiveness, especially in vault and dome construction; a genius for decoration with a freedom and success not rivaled in any other architecture”.[295]

Persians were among the first to use mathematics, geometry, and astronomy in architecture and also have extraordinary skills in making massive domes which can be seen frequently in the structure of bazaars and mosques. This greatly inspired the architecture of Iran’s neighbors as well. The main building types of classical Iranian architecture are the mosque and the palace. Besides being home to a large number of art houses and galleries, Iran also holds one of the largest and most valuable jewel collections in the world. Iran ranks seventh among countries in the world with the most archeological architectural ruins and attractions from antiquity as recognized by UNESCO.[296] Fifteen of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites are creations of Iranian architecture.

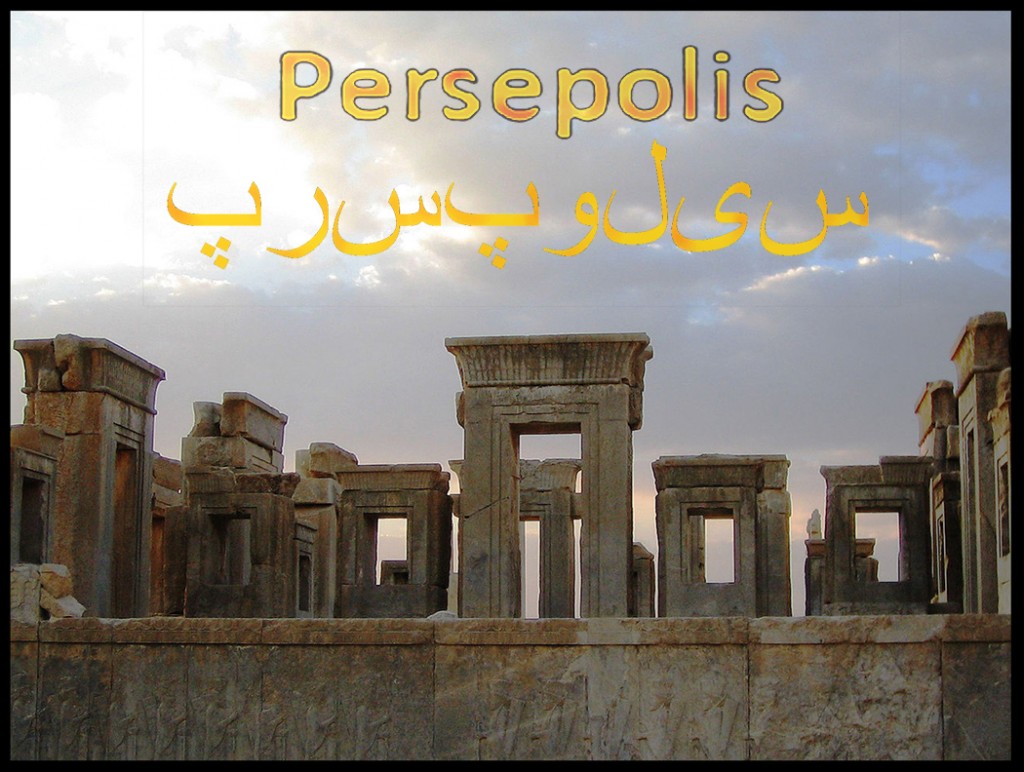

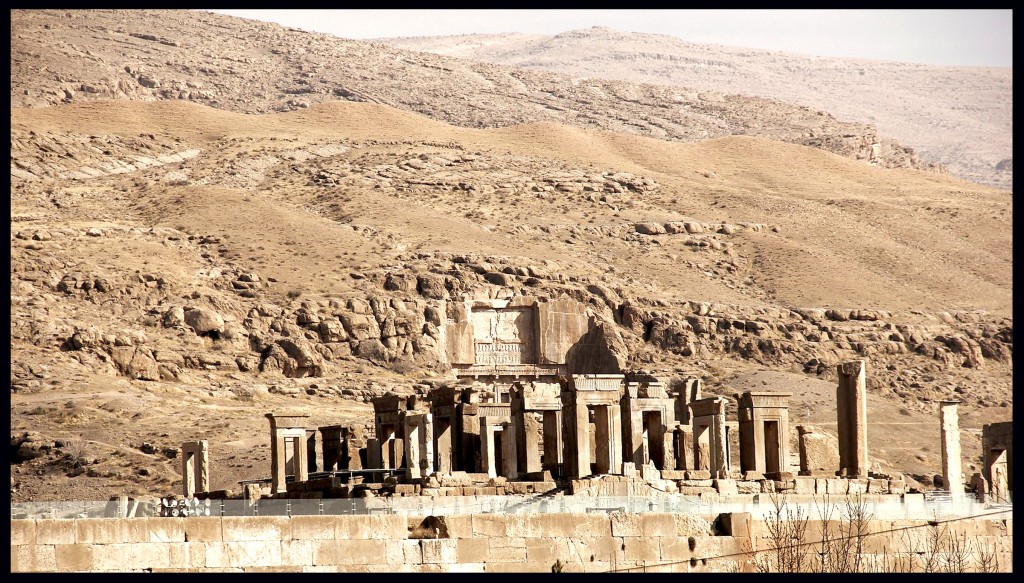

The ruins of Persepolis

The ruins of Persepolis

Shapour Xawst Castle in Khorram Abad City

Shapour Xawst Castle in Khorram Abad City

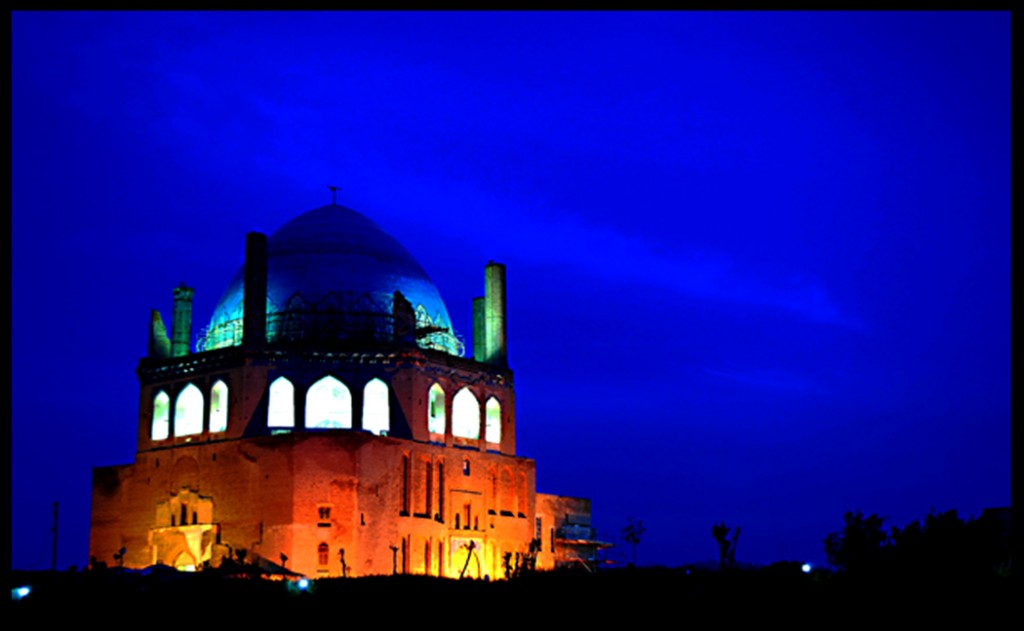

The Dome of Soltaniyeh

The Dome of Soltaniyeh

Ahmad Shah Qajar‘s Pavilion in Niavaran Palace Complex

Ahmad Shah Qajar‘s Pavilion in Niavaran Palace Complex

Entrance gate to the Shah Mosque in Isfahan

Entrance gate to the Shah Mosque in Isfahan

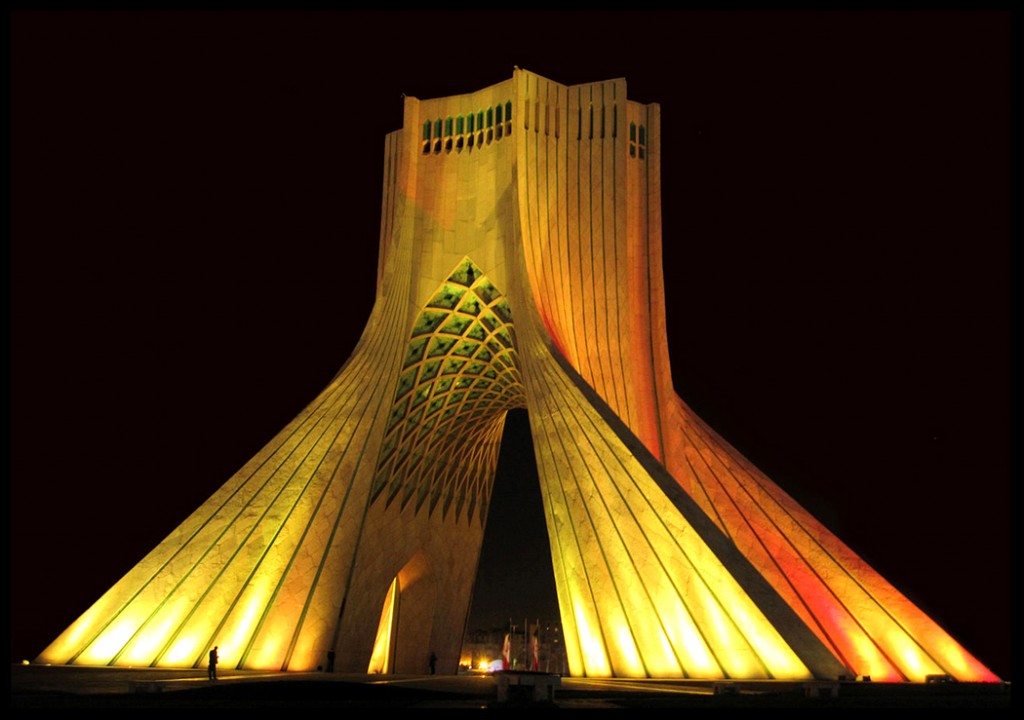

The Azadi Tower in Tehran

The Azadi Tower in Tehran

Literature: Persian literature

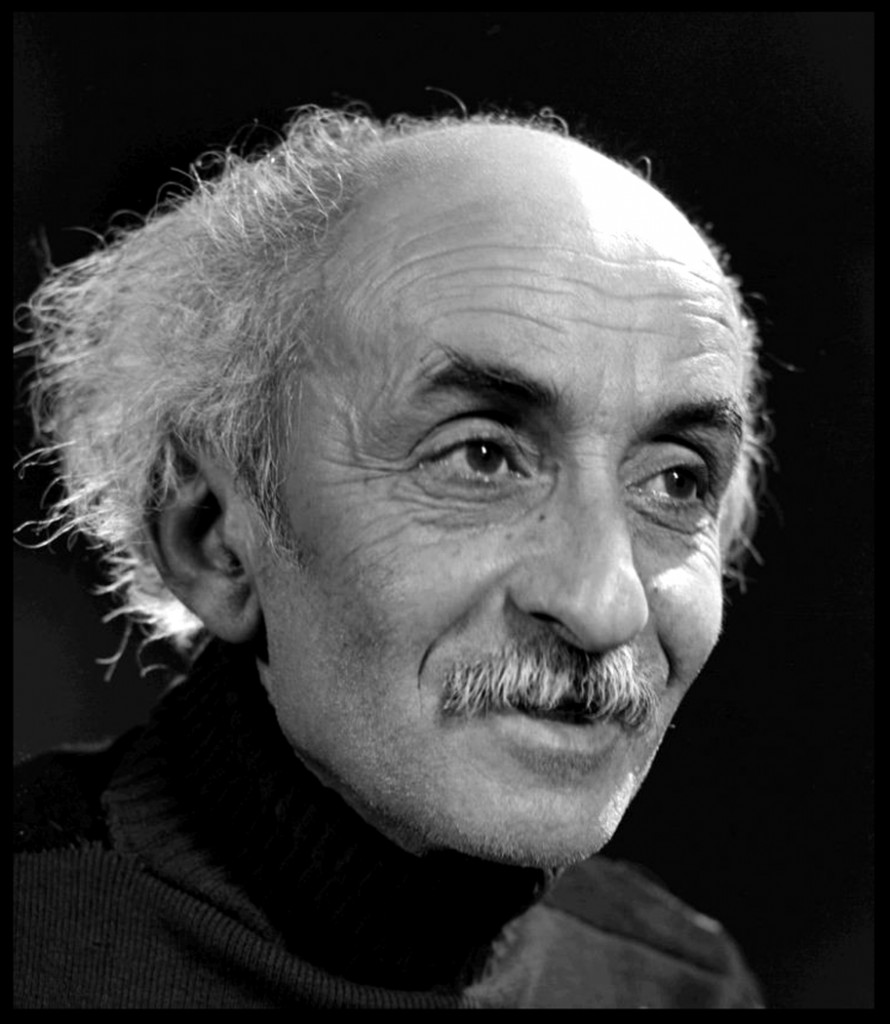

Nima Yooshij, father of modern Persian poetry

Nima Yooshij, father of modern Persian poetry

Persian literature is one of the world’s oldest literatures. It dates back to the poetry of Avesta, about 1000 years BC. These poems which were a part of the oral traditions of ancient Iran, were orally transferred, and later created parts of the Avesta’s book during the Sassanid era. Its sources have been within historical Persia where the Persian language has historically been the national language.

Persian literature inspired Goethe, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and many others, and it has been often dubbed as a most worthy language to serve as a conduit for poetry. Dialects of Persian are sporadically spoken throughout the region from China to Syria to Russia, though mainly in the Iranian Plateau.[297][298]

Poetry is used in many Persian classical works, whether from literature, science, or metaphysics. Persian literature has been considered by such thinkers as Goethe as one of the four main bodies of world literature.[299]

The Persian language has produced a number of famous poets; however, only a few poets as Rumi and Omar Khayyám have surfaced among western popular readership, even though the likes of Hafez, Saadi, Nizami,[300] Attar, Sanai, Nasir Khusraw and Jami are considered by many Iranians to be just as influential.[citation needed]

Philosophy: Iranian philosophy

The Fravarti symbol in Persepolis

The Fravarti symbol in Persepolis

Iranian philosophy can be traced back as far as to Old Iranian philosophical traditions and thoughts which originated in ancient Indo-Iranian roots and were considerably influenced by Zarathustra‘s teachings. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, the chronology of the subject and science of philosophy starts with the Indo-Iranians, dating this event to 1500 BC. The Oxford dictionary also states, “Zarathushtra’s philosophy entered to influence Western tradition through Judaism, and therefore on Middle Platonism.”

Throughout Iranian history and due to remarkable political and social changes such as the Arab and Mongol invasions of Persia, a wide spectrum of schools of thoughts showed a variety of views on philosophical questions extending from Old Iranian and mainly Zoroastrianism-related traditions, to schools appearing in the late pre-Islamic era such as Manicheism and Mazdakism as well as various post-Islamic schools.

Iranian philosophy after the Muslim conquest of Persia, is characterized by different interactions with the Old Iranian philosophy, the Greek philosophy and with the development of Islamic philosophy. The Illumination School and the Transcendent Philosophy are regarded as two of the main philosophical traditions of that era in Persia.

Mythology: Iranian mythology and Iranian folklore

Persian mythology are traditional tales and stories of ancient origin, all involving extraordinary or supernatural beings. Drawn from the legendary past of Iran, they reflect the attitudes of the society to which they first belonged – attitudes towards the confrontation of good and evil, the actions of the gods, yazats (lesser gods), and the exploits of heroes and fabulous creatures.

Myths play a crucial part in Iranian culture and understanding of them is increased when they are considered within the context of Iranian history.[citation needed] For this purpose we must ignore modern political boundaries and look at historical developments in the Greater Iran, a vast area covering the Caucasus, and Central Asia, beyond the frontiers of present-day Iran. The geography of this region, with its high mountain ranges, plays a significant role in many of the mythological stories. The 2nd millennium BC is usually regarded as the age of migration because of the emergence in western Iran of a new form of Iranian pottery, similar to earlier wares of north-eastern Iran, suggesting the arrival of the Ancient Iranian peoples. This pottery, light grey to black in colour, appeared around 1400 BC. It is called Early Grey Ware or Iron I, the latter name indicating the beginning of the Iron Age in this area.[301]

The central collection of Persian mythology is the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, written over a thousand years ago. Ferdowsi’s work draws heavily, with attribution, on the stories and characters of Mazdaism and Zoroastrianism, not only from the Avesta, but from later texts such as the Bundahishn and the Denkard as well as many others.

Theater

Main articles: Persian theater and Persian dance

Theater background in Persia goes back to antiquity (641–1000 BC).

The first initiation of theater and phenomena of acting in people of the land could be traced in the ceremonial theaters which were performed to glorify the heroes and humiliate the enemies, like Soug e Sivash or Mogh Koshi (Megakhouni), and also dances and theater narrations, and the musical history of mythological and love stories reported by Herodotos and Xenophon.

There were many dramatic performance arts popular before the advent of cinema in Persia. A few examples include Kheyme Shab Bazi (Puppetry), Saye Bazi (Shadow play), Rouhozi (Comical acts) and Tazieh (Martyr plays).

Rostam o Sohrab is an example of the opera performances in the modern day Iran.

Music: Music of Iran

Taq e Bostan carving, from 6th century Sassanian Iran.

Iranian music, as evidenced by the archeological records of Elam in southwestern Iran, dates back thousands of years. In ancient Iran musicians held socially respectable positions. The Elamites and the Achaemenids certainly made use of musicians.

The history of the musical performance in Sassanid Iran is, however, better documented than earlier periods. This is specially more evident in the context of Zoroastrian ritual.[302] By the time of Xusro Parviz the Sassanid royal court was the host of prominent musicians such as Ramtin, Bamshad, Nakisa, Azad, Sarkash, and Barbad.

Like most of the world’s cultures, the music of Persia has depended on oral transmission and learning.[303]

Persian symphonic music has a long history. In fact Opera originated from Persia, much before its emergence in Europe. Iranians traditionally performed Tazieh, which in many respects resembles the European Opera.[304] Iran’s main orchestra include National Orchestra, Tehran Symphony Orchestra, and Nations Orchestra.

Today the musical culture of Persia, while distinct, is closely related to other musical systems of the West and Central Asia. It has also affinities to the music cultures of the Indian subcontinent, to a certain degree even to those of Africa, and in the period after 1850 particularly, to that of Europe. Its history can be traced to some extent through these relationships.[citation needed]

Some Iranian traditional music instruments include the Saz, Iranian Tar, Azerbaijani Tar, Dotar, Setar, Kamanche, Harp, Barbat, Santur, Tanbur, Qanun, Dap, Tompak (Goblet drum), and Ney.

Cinema and animation: Cinema of Iran and History of Iranian animation

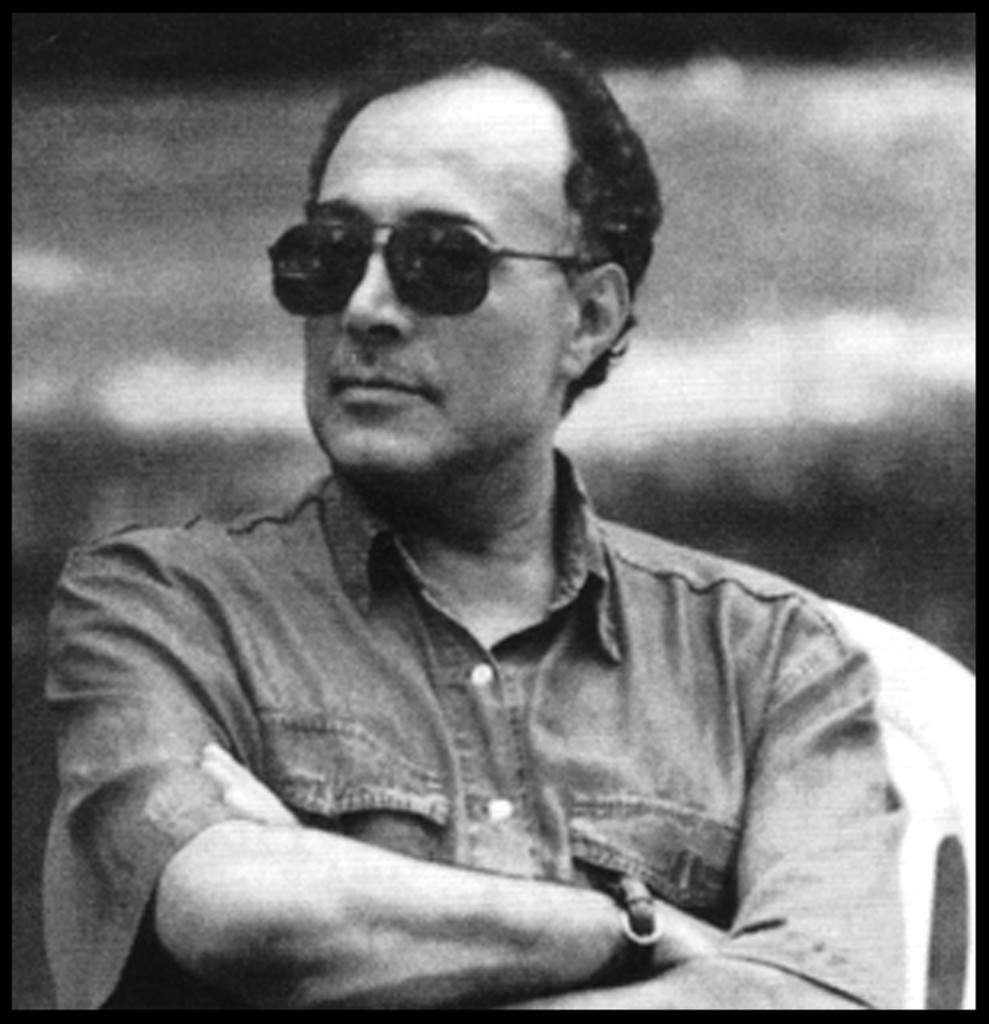

Abbas Kiarostami, a well-known Iranian director, at the Venice Film Festival

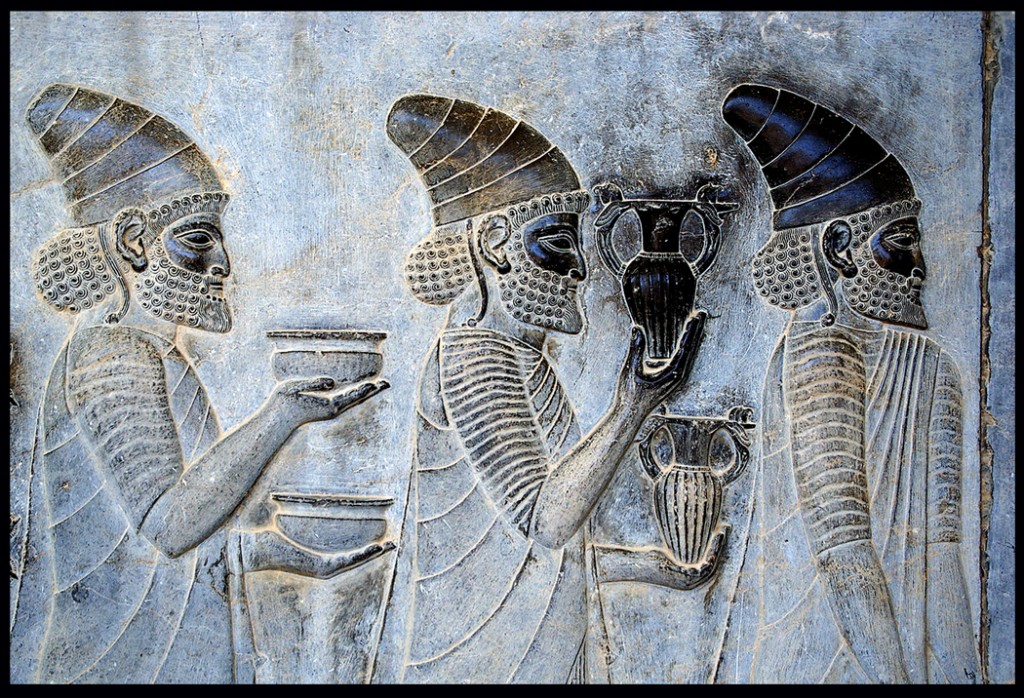

The earliest examples of visual representations in Iranian history may be traced back to the bas-reliefs in Persepolis (c. 500 BC). Persepolis was the ritual center of the ancient kingdom of Achaemenids and the figures at Persepolis remain bound by the rules of grammar and syntax of visual language.[305] During the Sasanian reign, Iranian visual arts reached a pinnacle. A bas-relief from this period in Taq e Bostan depicts a complex hunting scene. Similar works from the period have been found to articulate movements and actions in a highly sophisticated manner. It is even possible to see a progenitor of the cinema close-up in one of these works of art, which shows a wounded wild pig escaping from the hunting ground.[306]

In the early 20th century, five-year-old industry of cinema came to Iran. The first Iranian filmmaker was Mirza Ebrahim Khan (Akkas Bashi), the official photographer of Mozaffar al Din Shah of Qajar. He obtained a camera and filmed the Shah’s visit to Europe, upon the Shah’s orders.

In 1904, Mirza Ebrahim Khan (Sahhaf Bashi) opened the first movie theater in Tehran.[307] After him, several others like Russi Khan, Ardeshir Khan, and Ali Vakili tried to establish new movie theaters in Tehran. Until the early 1930s, there were little more than 15 theatres in Tehran and 11 in other provinces.[306]

The first silent Iranian film was made by Professor Ovanes Ohanian in 1930, and the first sounded one, Lor Girl, was made by Abd ol Hossein Sepanta in 1932.

The 1960s was a significant decade for Iranian cinema, with 25 commercial films produced annually on average throughout the early 60s, increasing to 65 by the end of the decade. The majority of production focused on melodrama and thrillers. With the screening of the films Kaiser and The Cow, directed by Masoud Kimiai and Dariush Mehrjui respectively in 1969, alternative films established their status in the film industry. Attempts to organize a film festival that had begun in 1954 within the framework of the Golrizan Festival, bore fruits in the form of the Sepas Festival in 1969. The endeavors also resulted in the formation of the Tehran World Festival in 1973.

After the Revolution of 1979, as the new government imposed new laws and standards, a new age in Iranian cinema emerged, starting with Viva… by Khosrow Sinai and followed by many other Iranian directors who emerged in the last few decades, such as Abbas Kiarostami and Jafar Panahi. Kiarostami, who some critics regard as one of the few great directors in the history of Iranian cinema,[308] planted Iran firmly on the map of world cinema when he won the Palme d’Or for Taste of Cherry in 1997. The continuous presence of Iranian films in prestigious international festivals, such as the Cannes Film Festival, the Venice Film Festival, and the Berlin Film Festival, attracted world attention to Iranian masterpieces.[309] In 2006, six Iranian films, of six different styles, represented Iranian cinema at the Berlin Film Festival. Critics considered this a remarkable event in the history of Iranian cinema.[310][311]

Asghar Farhadi, a well-known Iranian director, has received a Golden Globe Award and an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and was named as one of the 100 Most Influential People in the world by Time Magazine in 2012.

Other well-known Iranian directors include Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Majid Majidi, Bahram Beyzai, Bahman Ghobadi, Rakhshan Bani-E’temad, Amir Naderi, Ali Hatami and Reza Mirkarimi.

Marjane Satrapi, Shohreh Aghdashloo, Nazanin Boniadi, Shirin Neshat, Amir Mokri, Bahar Soomekh, Amir Talai, Nasim Pedrad, Daryush Shokof, and Rosie Malek-Yonan are among cinema people in the Iranian diaspora.

Reproduction of world’s oldest example of animation which belongs to late half of 3rd millennium BC, found in Burnt City, Iran.

Reproduction of world’s oldest example of animation which belongs to late half of 3rd millennium BC, found in Burnt City, Iran.

The oldest records of animation in Iran date back to the late half of 3rd millennium BC. An earthen goblet discovered at the site of the 5,200-year-old Burnt City in southeastern Iran, depicts what could possibly be the world’s oldest example of animation. The artifact bears five sequential images depicting a Persian Desert Ibex jumping up to eat the leaves of a tree.[312][313]

The art of animation, as practiced in modern day Iran, started in the 1950s. After four decades of animation production in Iran and three-decade experience of Kanoon Institute, Tehran International Animation Festival (TIAF) was established in February 1999. Every two years, participants from more than 70 countries attend this event which holds the biggest national animation market in Tehran.[314][315]

Cuisine: Iranian cuisine

Kuku Sabzi with herbs, topped with barberries and walnuts

Kuku Sabzi with herbs, topped with barberries and walnuts

The cuisine of Iran is diverse, with each province featuring dishes, culinary traditions and styles unique to their region. The main Persian cuisines feature combinations of rice with meat, chicken or fish and some onion, vegetables, nuts, and herbs. Herbs are frequently used along with fruits such as plums, pomegranates, quince, prunes, apricots, and raisins.

Iranians usually eat plain yogurt with lunch and dinner; it is a staple of the diet in Iran. To achieve a balanced taste, characteristic flavourings such as saffron, dried limes, cinnamon, and parsley are mixed delicately and used in some special dishes. Onions and garlic are normally used in the preparation of the accompanying course, but are also served separately during meals, either in raw or pickled form. Iranian cuisine has greatly inspired its neighbors.Iran is also famous for its caviar.[329]

For more information please visit Wikipedia. The link is: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran

For more information on “Iran nuclear talks: ‘Historic’ agreement struck” please visit BBC News. The link is:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-33518524

Royal Palace Of Achaemenid Empire Shah’s

Location: Fars Province, Iran[1]

Builder: Darius I and Xerxes I and Artaxerxes I

Material: Stone and Wood

Founded: 6th century BCE

Periods: Achaemenid Empire

Cultures: Persian

Events: Nowrooz, Celebrated from very beginning of construction (in addition to Tireg?n and Mehregan)

Management: Iranian Government

Public access: Open

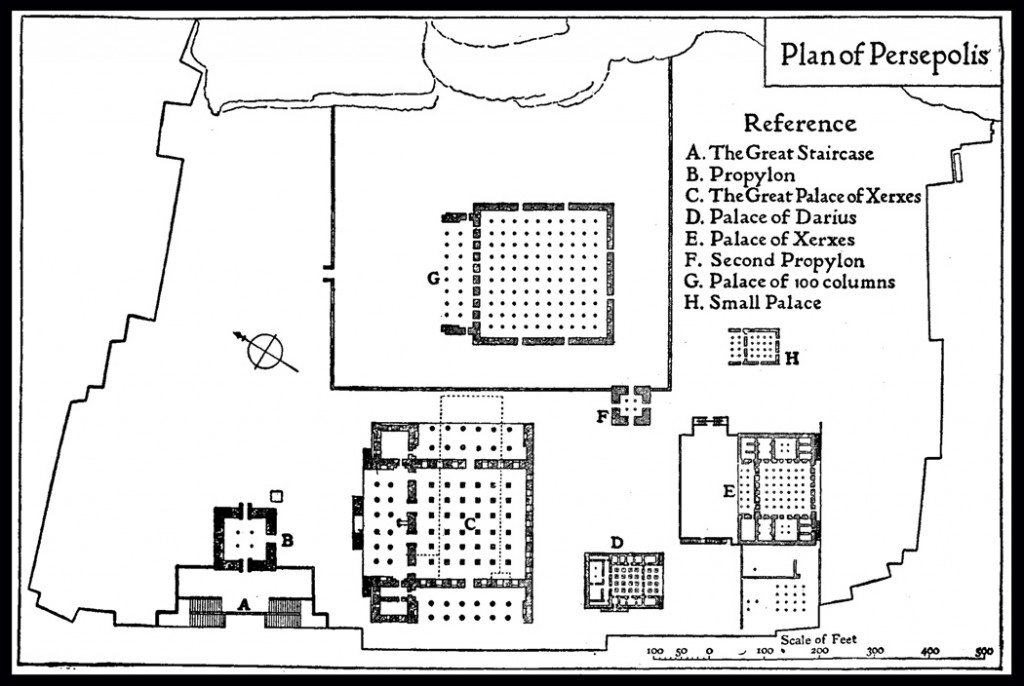

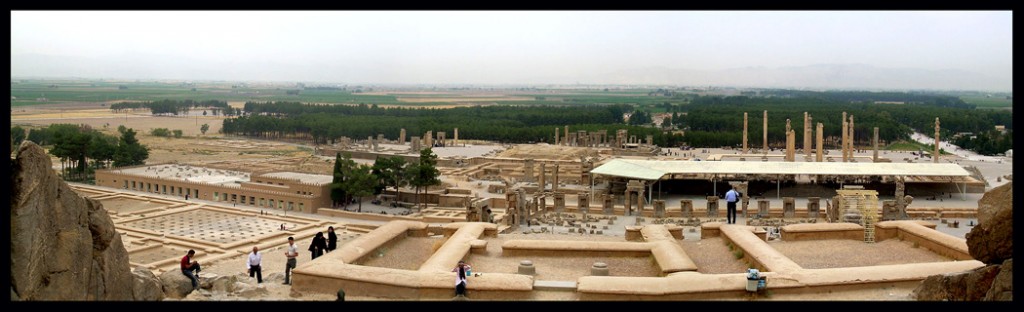

Persepolis (Old Persian: P?r?a,[2] New Persian: ??? ????? Takht-e Jamshid or ????? P?rseh), literally meaning “city of Persians”,[3] was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (ca. 550–330 BCE). Persepolis is situated 70 km northeast of city of Shiraz in Fars Province in Iran. The earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BCE. It exemplifies the Achaemenid style of architecture. UNESCO declared the ruins of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.[4]

Archaeological research

Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, a variety of amateur digging occurred at the site, in some cases on a large scale.[7] The first scientific excavations at Persepolis were carried out by Ernst Herzfeld and Erich Schmidt representing the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. They conducted excavations for eight seasons beginning in 1930 and included other nearby sites.[8][9][10][11][12]

Herzfeld believed the reasons behind the construction of Persepolis were the need for a majestic atmosphere, a symbol for their empire, and to celebrate special events, especially the “Nowruz“.[3] For historical reasons, Persepolis was built where the Achaemenid Dynasty was founded, although it was not the center of the empire at that time.

Persepolitan architecture is noted for its use of wooden columns. Architects resorted to stone only when the largest cedars of Lebanon or teak trees of India did not fulfill the required sizes. Column bases and capitals were made of stone, even on wooden shafts, but the existence of wooden capitals is probable.

The buildings at Persepolis include three general groupings: military quarters, the treasury, and the reception halls and occasional houses for the King. Noted structures include the Great Stairway, the Gate of Nations (Xerxes the Great), the Apadana Palace of Darius, the Hall of a Hundred Columns, the Tripylon Hall and Tachara Palace of Darius, the Hadish Palace of Xerxes, the palace of Artaxerxes III, the Imperial Treasury, the Royal Stables, and the Chariot House.[13]

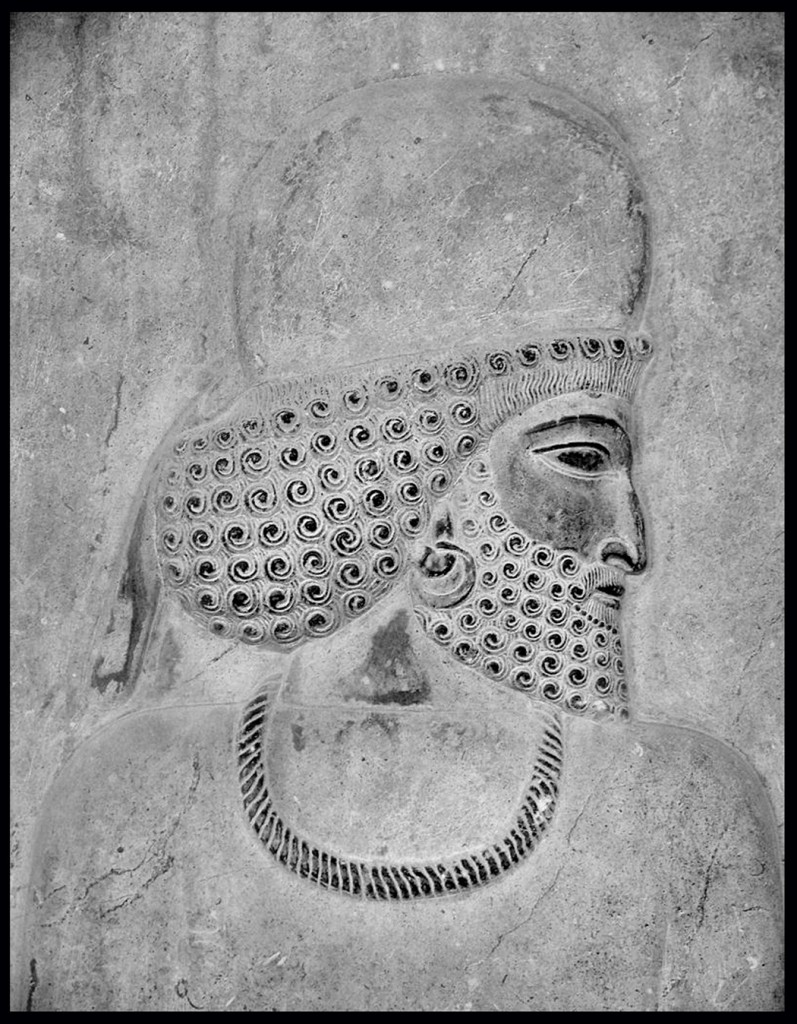

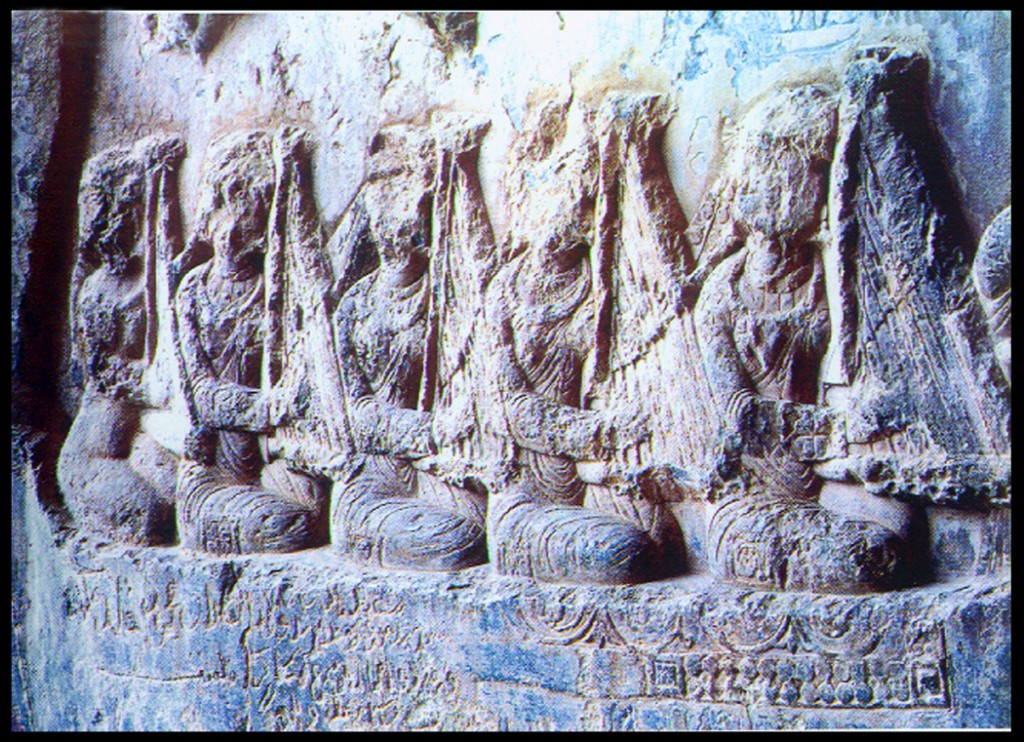

Frieze statues depicting Persian and Median nobleman in friendly conversation.

Frieze statues depicting Persian and Median nobleman in friendly conversation.

Aeria architectural plan of Persepolis

Aeria architectural plan of Persepolis

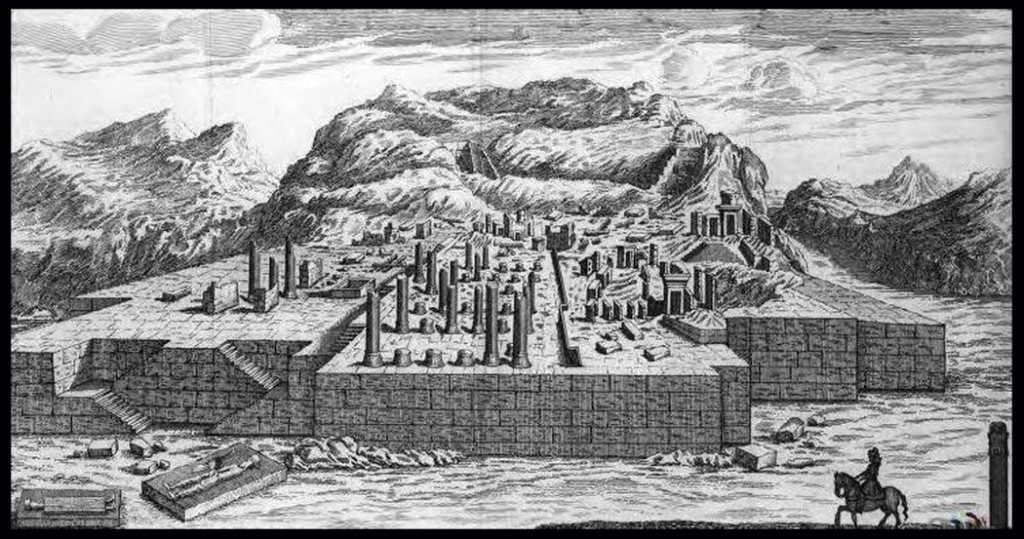

Drawing of Persepolis in 1713 by Gérard Jean-Baptiste

Drawing of Persepolis in 1713 by Gérard Jean-Baptiste

Geographic location

Persepolis is near the small river Pulvar, which flows into the river Kur (derived from Persian word Cyrus / Kuroush). The site includes a 125,000 square metre terrace, partly artificially constructed and partly cut out of a mountain, with its east side leaning on Kuh-e Rahmet (“the Mountain of Mercy”). The other three sides are formed by retaining walls, which vary in height with the slope of the ground. From 5 to 13 metres on the west side a double stair. From there it gently slopes to the top. To create the level terrace, depressions were filled with soil and heavy rocks, which were joined together with metal clips.

19th century reconstruction by Flandin & Pascal Coste

19th century reconstruction by Flandin & Pascal Coste

Sunset in Perspolis.

Sunset in Perspolis.

Ruins

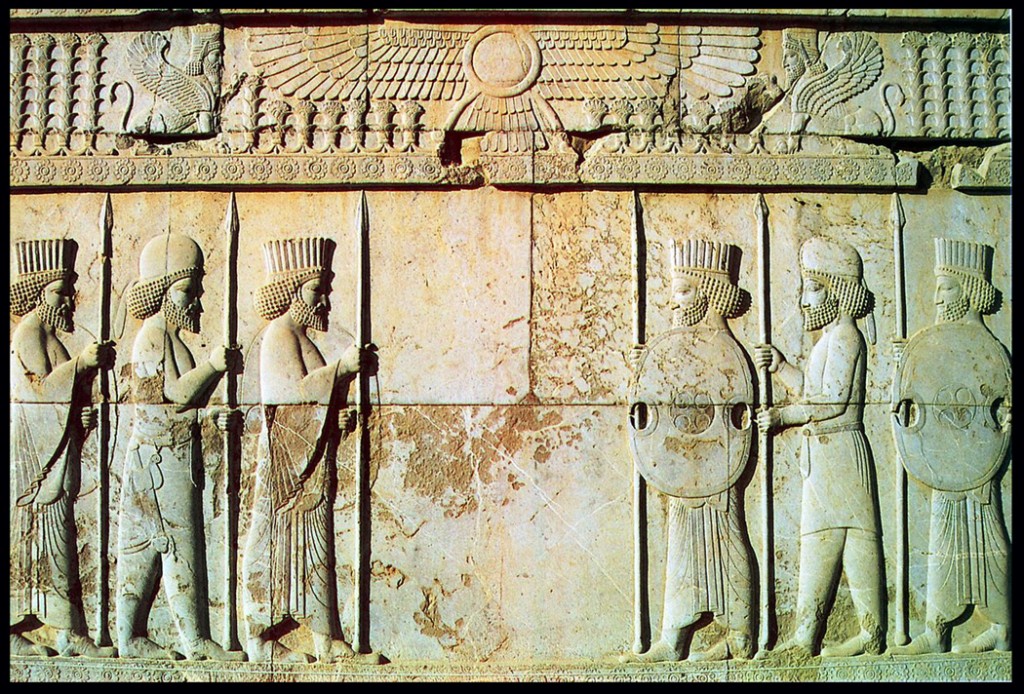

The Apadana Palace, northern stairway, showing a Persian followed by a Mede soldier in traditional costume

The Apadana Palace, northern stairway, showing a Persian followed by a Mede soldier in traditional costume

Behind Takht-e Jamshid are three sepulchres hewn out of the rock in the hillside. The façades, one of which is incomplete, are richly decorated with reliefs. About 13 km NNE, on the opposite side of the Pulwar, rises a perpendicular wall of rock, in which four similar tombs are cut at a considerable height from the bottom of the valley. The modern Persians call this place ??? ???? Naqsh-e Rostam, from the Sassanid reliefs beneath the opening, which they take to be a representation of the mythical hero Rostam. It may be inferred from the sculptures that the occupants of these seven tombs were kings. An inscription on one of the tombs declares it to be that of Darius Hystaspis, concerning whom Ctesias relates that his grave was in the face of a rock, and could only be reached by the use of ropes. Ctesias mentions further, with regard to a number of Persian kings, either that their remains were brought “to the Persians,” or that they died there.

Bas-relief in Persepolis—a symbol in Zoroastrian for Nowruz— eternally fighting bull (personifying the moon), and a lion (personifying the Sun) representing the Spring.

Bas-relief in Persepolis—a symbol in Zoroastrian for Nowruz— eternally fighting bull (personifying the moon), and a lion (personifying the Sun) representing the Spring.

Two Persian Soldiers in Persepolis

Two Persian Soldiers in Persepolis

Detail of a relief of the eastern stairs of the Apadana

Detail of a relief of the eastern stairs of the Apadana

Gate of All Nations: Gate of All Nations

gate of nations

The Gate of all Nations, referring to subjects of the empire, consisted of a grand hall that was a square of approximately 25 metres (82 ft) in length, with four columns and its entrance on the Western Wall. There were two more doors, one to the south which opened to the Apadana yard and the other opened onto a long road to the east. Pivoting devices found on the inner corners of all the doors indicate that they were two-leafed doors, probably made of wood and covered with sheets of ornate metal.

A pair of Lamassus, bulls with the heads of bearded men, stand by the western threshold. Another pair, with wings and a Persian head (Gopät-Shäh), stands by the eastern entrance, to reflect the Empire’s power.

Xerxes’s name was written in three languages and carved on the entrances, informing everyone that he ordered it to be built.

Median man in Persepolis relief

Median man in Persepolis relief

Tachara palace

Tachara palace

Apadana Hall, Persian and Median soldiers

Apadana Hall, Persian and Median soldiers

Part of the Hall of a Hundred Columns with the Tomb of King Artaxerxes III in the background

Tombs of Kings: Tomb of Cyrus

Lapis lazuli and paste plaque from Persepolis (National Museum of Iran)

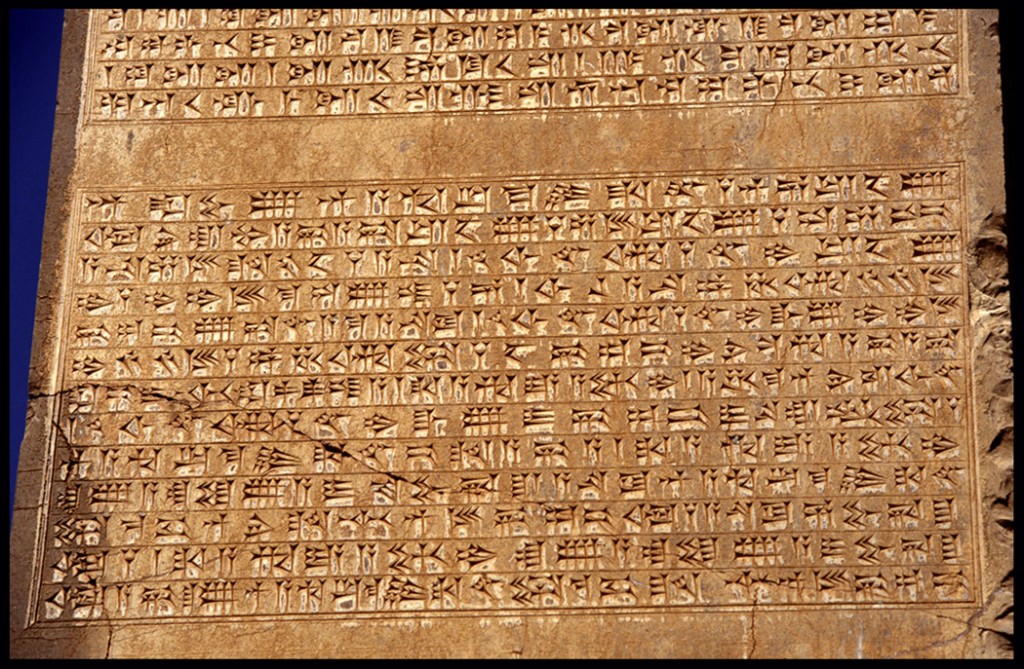

Ancient texts

Babylonian version of the Achaemenid royal inscriptions known as XPc (Xerxes Persepolis c) from the portico of the “Palace of Darius” at Persepolis.

Babylonian version of the Achaemenid royal inscriptions known as XPc (Xerxes Persepolis c) from the portico of the “Palace of Darius” at Persepolis.

Destruction

After invading Persia, Alexander the Great sent the main force of his army to Persepolis in the year 330 BC by the Royal Road. Alexander stormed the Persian Gates (in the modern Zagros Mountains), then quickly captured Persepolis before its treasury could be looted. After several months Alexander allowed his troops to loot Persepolis.

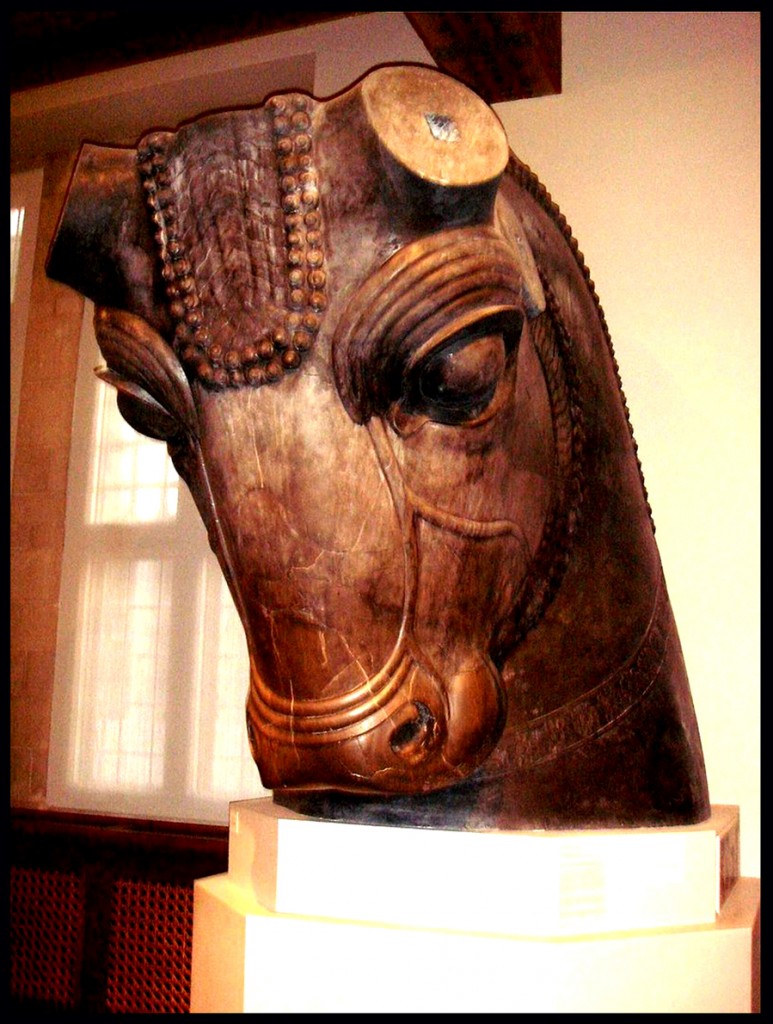

Head of Bull now at Oriental Institute, Chicago

Head of Bull now at Oriental Institute, Chicago

A Persepolis frieze depicting the Persian Immortals

A Persepolis frieze depicting the Persian Immortals

Achaemenid griffin at Persepolis.

Achaemenid griffin at Persepolis.

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire

In 316 BC Persepolis was still the capital of Persia as a province of the great Macedonian Empire (see Diod. xix, 21 seq., 46 ; probably after Hieronymus of Cardia, who was living about 316). The city must have gradually declined in the course of time – the lower city at the foot of imperial city might have survived for a longer time;[19] but the ruins of the Achaemenidae remained as a witness to its ancient glory. It is probable that the principal town of the country, or at least of the district, was always in this neighborhood.

About 200 BC the city Istakhr (properly Estakhr), five kilometers north of Persepolis, was the seat of the local governors. From there the foundations of the second great Persian Empire were laid, and there Istakhr acquired special importance as the center of priestly wisdom and orthodoxy. The Sassanian kings have covered the face of the rocks in this neighborhood, and in part even the Achaemenian ruins, with their sculptures and inscriptions. They must themselves have been built largely there, although never on the same scale of magnificence as their ancient predecessors. The Romans knew as little about Istakhr as the Greeks had known about Persepolis—and this despite the fact that for four hundred years the Sassanians maintained relations, friendly or hostile, with the empire.

At the time of the Arabian conquest, Istakhr offered a desperate resistance. The city was still a place of considerable importance in the first century of Islam, although its greatness was speedily eclipsed by the new metropolis Shiraz. In the 10th century, Istakhr dwindled to insignificance, as may be seen from the descriptions of Istakhri, a native (c. 950), and of Mukaddasi (c. 985). During the following centuries, Istakhr gradually declined, until, as a city, it ceased to exist.

In 1618, García de Silva Figueroa, King Philip III of Spain‘s ambassador to the court of Shah Abbas, the Safavid Monarch, was the first Western traveler to correctly identify the ruins of Takht-e Jamshid as the location of Persepolis.[20]

Pietro della Valle vistied Persepolis in 1621 and noticed that of the original columns only 25 of the 72 original columns were standing either due to vandalism or natural processes.[21]

The Dutch traveler Cornelis de Bruijn visited Persepolis in 1704. He was the first westerner who made drawings of Persepolis.[22]

The fruitful region was covered with villages till the frightful devastation in the 18th century; and even now it is, comparatively speaking, well cultivated. The “castle of Istakhr” played a conspicuous part several times during the Muslim period as a strong fortress. It was the middlemost and the highest of the three steep crags which rise from the valley of the Kur, at some distance to the west or northwest of Nakshi Rustam.

French voyagers Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste are among the first to provide not only a literary review of the structure of Persepolis but also to create some of the best and earliest visual depictions of its structure. In their publications in Paris in 1881 and 1882, titled “Voyages en Perse de MM. Eugene Flanin peintre et Pascal Coste architect” the authors provide some 350 ground breaking illustrations of Persepolis.[7] French influence and interest in Persia’s archeological findings would not end until time of Reza Shah where such distinguished figures as Andrea Goddard helped create Iran’s first heritage museum.

Graffiti from foreign visitors.

Graffiti from foreign visitors.

Modern events

In 1971, Persepolis was the main staging ground for the 2,500 year celebration of Iran’s monarchy. It included delegations from foreign nations in an attempt to advance Persian culture.

Sivand Dam Controversy

Construction of the Sivand Dam, named for the nearby town of Sivand, began September 19, 2006. Despite 10 years of planning, Iran’s own Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization was not aware of the broad areas of flooding during much of this time[citation needed] and there is growing concern about the effects the dam will have on Persepolis’s surrounding areas.

Many archaeologists[who?] and Iranians worry that the dam’s placement between the ruins of Pasargadae and Persepolis will flood both these UNESCO World Heritage sites. Engineers involved with the construction refute this claim, stating its impossible because both sites sit well above the planned waterline. Of the two sites, Pasargadae is considered the more threatened.

Archaeologists are also concerned that an increase in humidity caused by the lake will speed Pasargadae’s gradual destruction, however, experts from the Ministry of Energy believe this would be negated by controlling the water level of the dam reservoir.

Museums (outside of Iran) that display material from Persepolis

The British Museum has an outstanding collection. The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England has a number of bas reliefs from Persepolis.[23] The Persepolis bull at the Oriental Institute, Chicago is one of the university’s most prized treasures, but it is only one of several objects from Persepolis on display at the University of Chicago. The Metropolitan Museum houses objects from Persepolis,[24] as does the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.[25] In France, the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Lyon[26] and the musée du Louvre in Paris hold objects from Persepolis too.

Panoramic view

Humans walk in the long steps of history leaving remnants of each step of life and each generation. The vestiges that journey pass on what has happened in the past for the next generation to learn. To destroy these remnants, these ancient monuments, is to destroy oneself. We learn from the past for better or worse. These testaments to antiquity belong to every one of us to learn, respect and preserve for younger generations to be able walk firmly, more educated, becoming better human beings, surviving together with a more civilized and peaceful society for all.

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Wednesday, July 15, 2015

More of Iranian Art

Painting and miniature

Mihr ‘Ali (Iranian, active ca. 1800-1830). Portrait of Fath Ali Shah Qajar, 1815. Brooklyn Museum

Mullahs in the royal presence. The painting style is markedly Qajari. Persian painting

Mullahs in the royal presence. The painting style is markedly Qajari. Persian painting

Pottery and ceramics

Pottery Vessel, Fourth Millennium BC. The Sialk collection of Tehran‘s National Museum of Iran.

Pottery Vessel, Fourth Millennium BC. The Sialk collection of Tehran‘s National Museum of Iran.

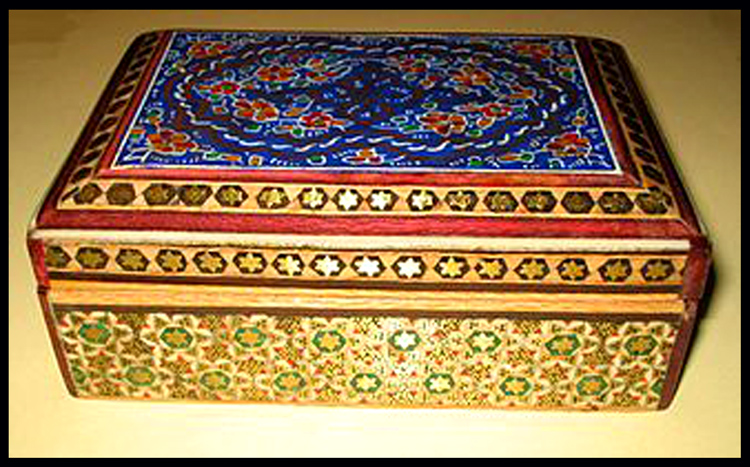

Khatam-kari

Box painted and decorated with Khatam kari marquetry, a typical kind of work in wood from Iran.

The Qajarid reliefs of Tangeh Savashi were made by order of Fath Ali Shah

Mihr ‘Ali (Iranian, active ca. 1800-1830). Portrait of Fath ‘Ali Shah Qajar, 1815. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 3 1/2 x 5 in. (8.9 x 12.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Laura L. Barnes, David Ellis, Mr. and Mrs. Alfred H. Otto, Mabel Reiner, and anonymous gifts, by exchange, 2005.56

Mihr ‘Ali (Iranian, active ca. 1800-1830). Portrait of Fath ‘Ali Shah Qajar, 1815. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 3 1/2 x 5 in. (8.9 x 12.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Laura L. Barnes, David Ellis, Mr. and Mrs. Alfred H. Otto, Mabel Reiner, and anonymous gifts, by exchange, 2005.56

Persian Silk Brocade. Persian Textile (The Golden Yarns of Zari – Brocade). Silk Brocade with Golden Thread (Golabetoon) Sialkgraph – Own work

Iranian Traditional and Ancient Art (Mahrooq Holy Shrine in Neyshabour…)

For more information please visit Wikipedia. The links are:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persepolis

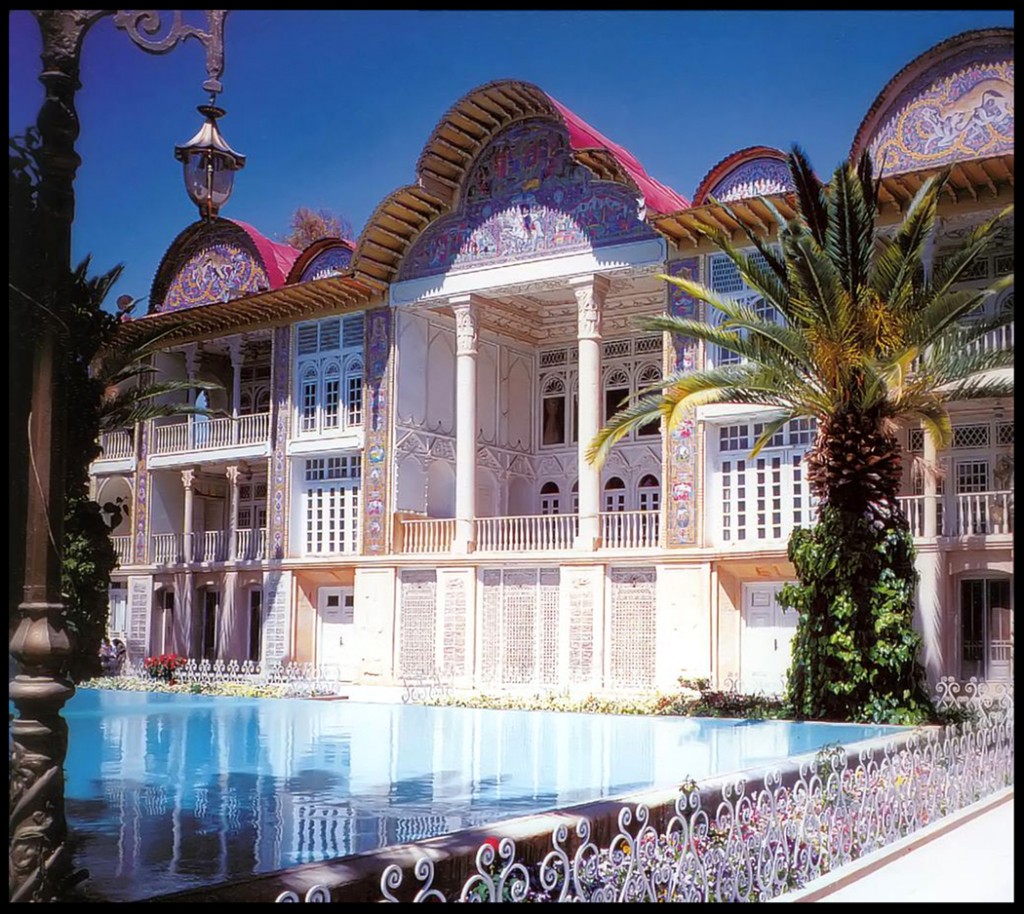

Eram Garden

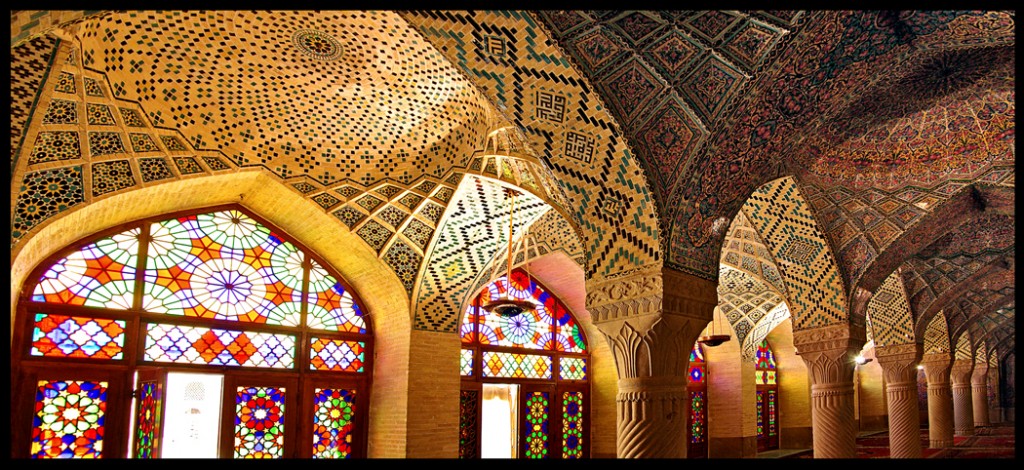

Eram Garden Nasir ol Molk Mosque

Nasir ol Molk Mosque Ferdows Garden

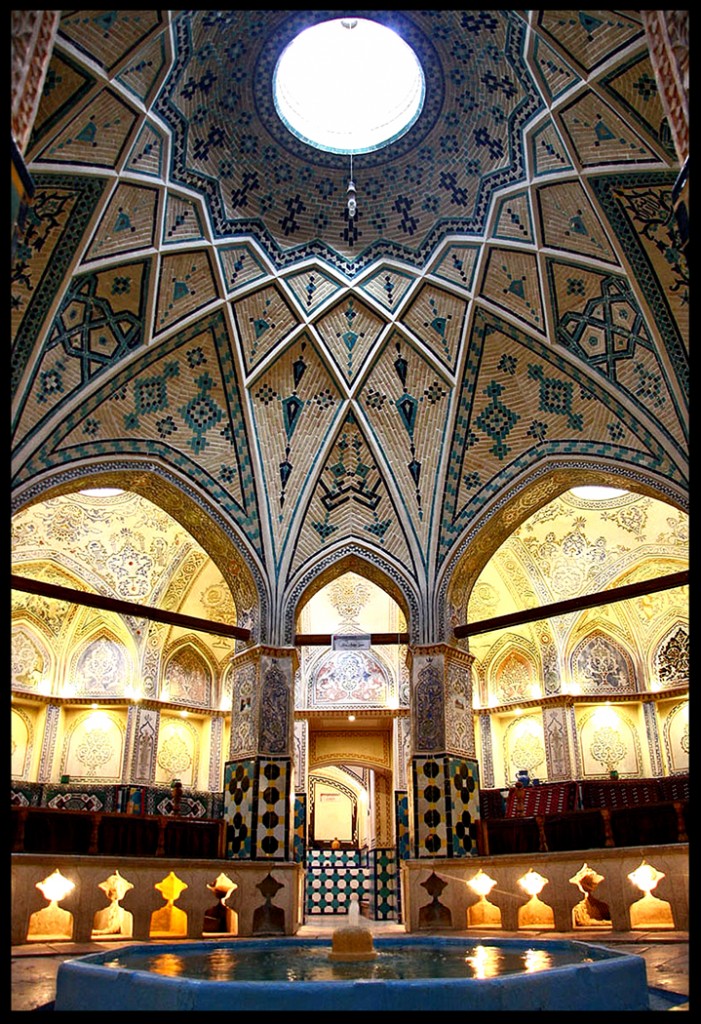

Ferdows Garden Qasemi Bathhouse

Qasemi Bathhouse

Rustam Inscription

Rustam Inscription

Shedu

Shedu

Gate of All Nations

Gate of All Nations

Leave a Reply