Artwork by Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts

Artwork by Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts

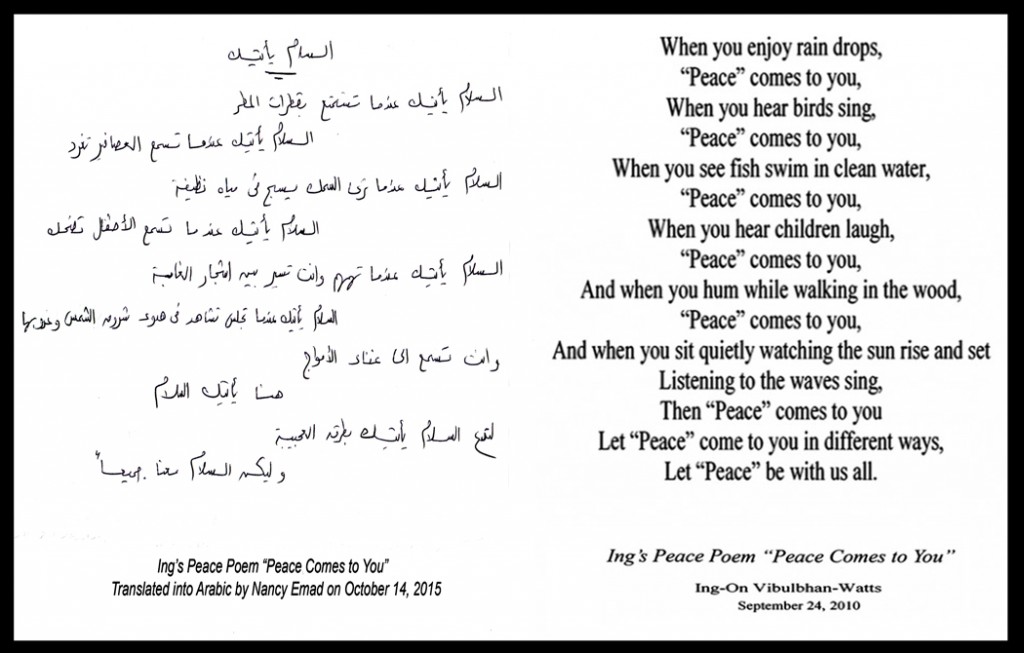

Ing’s Peace Poem Translated into Arabic

And Egyptian Art History Part 4

Ing’s Peace Poem “Peace Comes to You”

Translated into Arabic by Nancy Emad on October 14, 2015

Artwork by Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts

Artwork by Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts

Art, Architecture, and the City in the Reign of Amenhotep IV / Akhenaten (ca. 1353–1336 B.C.)

The seventeen-year reign of the pharaoh Amenhotep IV / Akhenaten is remarkable as revealing ideas, architecture, and art that stand out as different against Egypt’s long tradition.

As a beehive of building and production, the city provides many insights into ancient industry and technology, from construction, to manufacture of glass and faience, to statuary and textile production, to bread making.

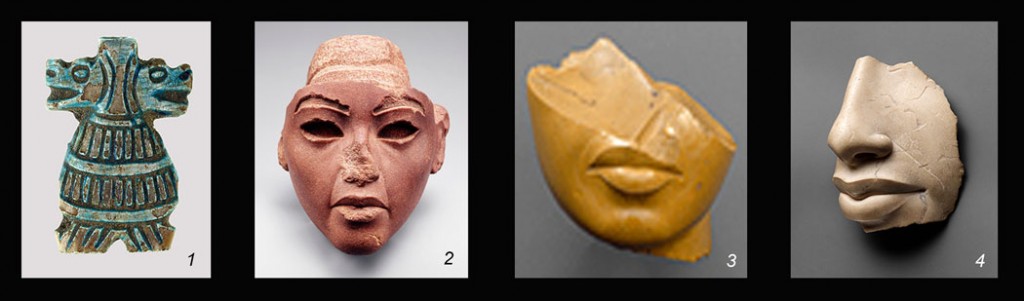

1. Taweret amulet with double head, New Kingdom, late Dynasty 18–Dynasty 19, ca. 1390–1213 b.c., Egyptian; from Egypt, Blue faience

1. Taweret amulet with double head, New Kingdom, late Dynasty 18–Dynasty 19, ca. 1390–1213 b.c., Egyptian; from Egypt, Blue faience

2. Head of Queen Tiye, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, ca. 1388–1340 b.c., Egyptian, Red quartzite

3. Fragment of the face of a queen, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egypt, Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten); inc. el-Hagg Qandil, Yellow jasper

4. Nose and lips of Akhenaten, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from el-Amarna (Akhetaten), inc. el-Hagg Qandil, Great Aten Temple, pit outside southern wall, Petrie/Carter 1891–92, Indurated limestone

5. Fragmentary statuette of a vizier, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Egypt, Indurated limestone

5. Fragmentary statuette of a vizier, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Egypt, Indurated limestone

6. Head from a statuette, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten), inc. el-Hagg Qandil, House no. 68 (T36.68), EES 1930–31, Limestone, paint

7. Statue of two men and a boy that served as a domestic icon, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from southern Upper Egypt, Gebelein (Nag el-Gharira; Krokodilopolis), Limestone, paint

8. Torso of Akhenaten, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten), inc. el-Hagg Qandil, Great Aten Temple, pit outside southern wall, Petrie/Carter 1891–92

Indurated limestone

9. Goblet inscribed with the names of King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Egypt, Travertine (Egyptian alabaster)

9. Goblet inscribed with the names of King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Egypt, Travertine (Egyptian alabaster)

10. Blue-painted storage jar, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Egypt, Pottery

11. Finger ring of King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten), inc. el-Hagg Qandil, Town, Petrie 1891–92, Gold

12. Talatat with Offerings in the Temple, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten), inc. el-Hagg Qandil, Great Aten Temple, pit outside southern wall, Petrie/Carter 1891–92

12. Talatat with Offerings in the Temple, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten), inc. el-Hagg Qandil, Great Aten Temple, pit outside southern wall, Petrie/Carter 1891–92

Limestone, paint

13. Tile with persea fruit and leaves, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten), inc. el-Hagg Qandil, Royal Palace of Akhenaten, Petrie 1891–92, Polychrome faience

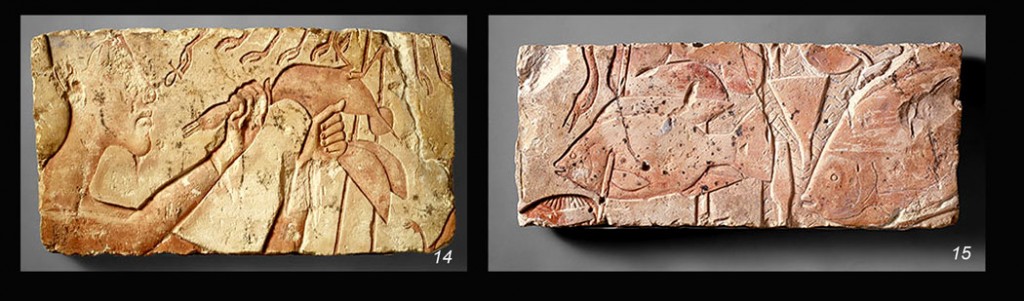

14. Akhenaten Sacrificing a Duck, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 B.C., Egyptian, Limestone

14. Akhenaten Sacrificing a Duck, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 B.C., Egyptian, Limestone

15. Scene of Fishing and Fowling, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, probably el-Amarna, possibly Hermopolis, Limestone, paint

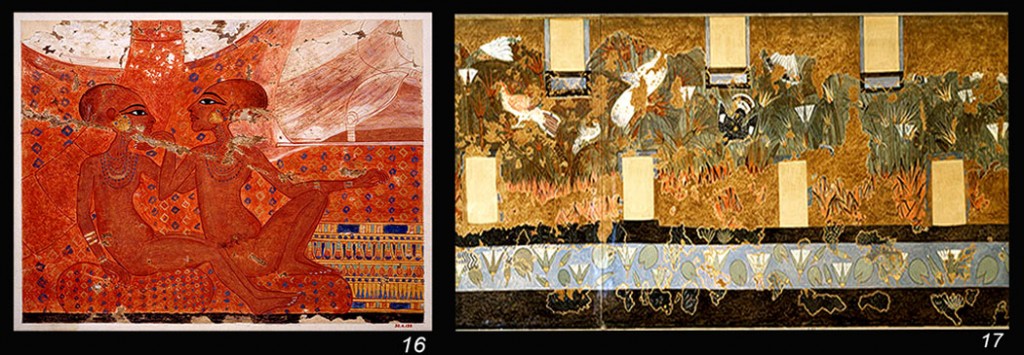

16. Two Princesses, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten), inc. el-Hagg Qandil, King’s House Color facsimile by Nina deGaris Davies (1881–1965), Tempera on paper

16. Two Princesses, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten), inc. el-Hagg Qandil, King’s House Color facsimile by Nina deGaris Davies (1881–1965), Tempera on paper

17. “Green Room” in the North Palace at Amarna, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c., Egyptian; original from Amarna, North Palace, Color facsimile by Norman (1865–1941) or Nina de Garis Davies (1881–1965), Tempera on paper

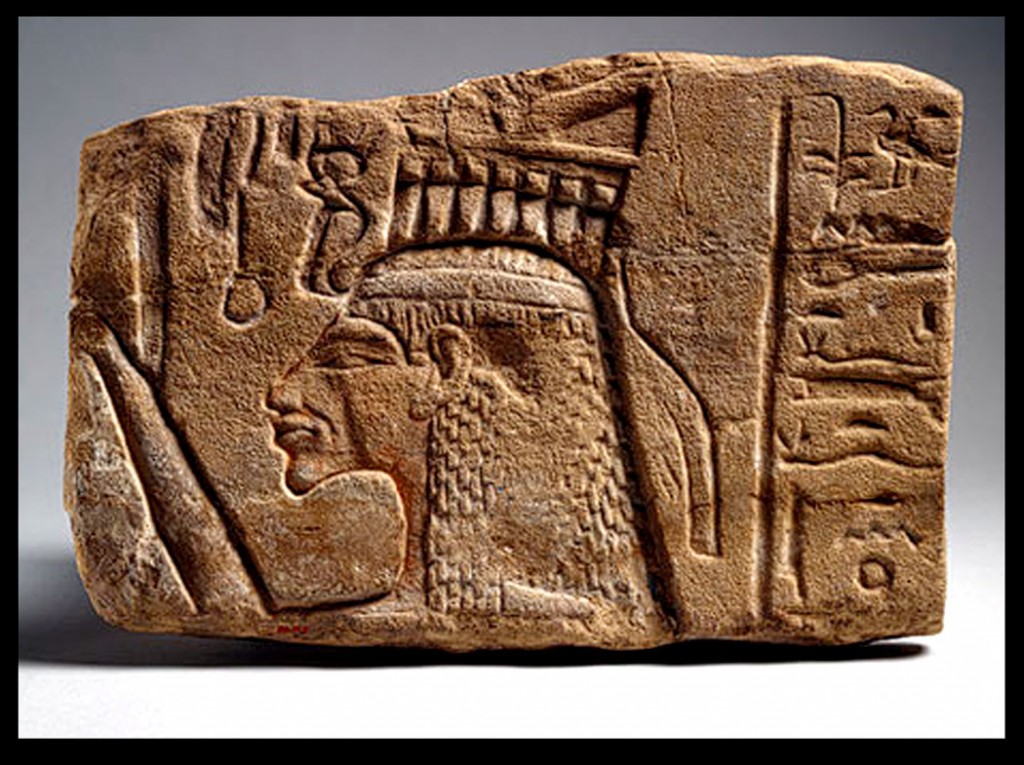

Relief of Queen Nefertiti, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1352–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Upper Egypt, Thebes, probably Karnak, Sandstone H. 8 11/16 in. (22 cm), W. 12 5/8 in. (32 cm), Rogers Fund, 1961 (61.117)

Relief of Queen Nefertiti, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1352–1336 b.c., Egyptian; from Upper Egypt, Thebes, probably Karnak, Sandstone H. 8 11/16 in. (22 cm), W. 12 5/8 in. (32 cm), Rogers Fund, 1961 (61.117)

Nefertiti, whose name means “the Beautiful One Is Here,” was principal queen of Akhenaten. Like her mother-in-law Queen Tiye, Nefertiti was a powerful figure in the court. She is frequently shown participating in religious rituals on an equal footing with her husband, and she already played an unprecedented role in the decoration of the Aten structures that Amenhotep IV built at Karnak, from which this block almost certainly came, before his move to Tell el-Amarna.

This relief block shows the queen wearing an elaborate wig surmounted by what was originally a towering crown of uraei, sun disk, two cow horns, and two feathers. Her arm is raised in offering to the Aten. The queen’s image is rendered in an exaggerated style seen in some earlier Amarna art, with a drooping chin, thin slanted eyes, and a sharply angled nose and brow, similar to that seen in depictions of her husband (see 66.99.40).

In fact, as one specialist in Amarna art has recently pointed out, the traces of the Aten rays around the queen’s face and arms indicate the disk was almost directly overhead. The queen must have stood alone, without her husband, beneath the rays. She would have been followed by a small figure of her eldest daughter, labeled in the column of hieroglyphs behind her head. The unusual arrangement is known from the pylons of the early Temple of the Benben at Karnak, and from some enigmatic structures known as the Pillars of Nefertiti. The relief may well have originated in one of these structures.

Jewelry elements for a broad collar, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c.

Jewelry elements for a broad collar, New Kingdom, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, ca. 1353–1336 b.c.

Egyptian; from Middle Egypt, el-Amarna (Akhetaten), EES 1928–29 (neg. 121b), 1930–31

Faience, H. 5 1/8 in. (13 cm), W. 16 15/16 in. (43 cm)

Gift of Mrs. John Hubbard and Egypt Exploration Society, 1931 (31.114.2a) These faience necklace elements were excavated at Amarna. The beads include palm fronds (green), lotus petals (white), dates (green, blue, and red), bunches of grapes (dark blue), cornflowers (green, blue, and white), persea fruit (yellow), and dom-palm fruit (red). The individual beads were made in molds and small ring beads were attached later to allow stringing. These elements were intended for a collar necklace, so rings were attached at top and bottom so that the beads could interlock two strings. The triangular necklace terminal in the shape of a lotus blossom was pierced with holes for the necklace threads before it was fired. These jewelry elements come from houses in the North Suburb of Amarna where there were sites with a high density of faience molds and pendants, suggesting production took place in those areas.

Shortly after coming to the throne, the new pharaoh Amenhotep IV, a son of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye, established worship of the light that is in the orb of the sun (the Aten) as the primary religion, and the many-armed disk became the omnipresent icon representing the god. The new religion, with its emphasis on the light of the sun and on what can be seen, went together with new emphases on time, movement, and atmosphere in the arts. Exceptional as the new outlook seems, it certainly had roots in the increasing prominence of the solar principle, or Re, in the earlier eighteenth dynasty, and in the emphasis on the all-pervasive quality of the god Amun-Re, developments reaching a new height in the reign of Amenhotep III (ca. 1390–1353 B.C.). Likewise, artistic changes were afoot before the reign of Amenhotep IV / Akhenaten. For example, Theban tombs of Dynasty 18 had begun to redefine artistic norms, exploring the possibilities of line and color for suggesting movement and atmospherics or employing more natural views of parts of the body.

While the art and texts of what is commonly called the Amarna Period after the site of the new city for the Aten are striking, and their naturalistic imagery easy to appreciate, it is more difficult to bring the figure of Amenhotep IV / Akhenaten himself or the lived experiences of Atenism into focus. The courtiers who helped the king monumentalize his vision refer to a kind of teaching that the king provided, to them at a minimum, and the art and particular hymns or prayers convey a striking appreciation of the physical world.

Beautifully you appear from the horizon of heaven, O living Aten who initiates life—

For you are risen from the eastern horizon and have filled every land with your beauty;

For you are fair, great, dazzling and high over every land,

And your rays enclose the lands to the limit of all you have made;

For you are Re, having reached their limit and subdued them for your beloved son;

For although you are far away, your rays are upon the earth and you are perceived.

When your movements vanish and you set in the western horizon,

The land is in darkness, in the manner of death.

(People), they lie in bedchambers, heads covered up, and one eye does not see its fellow.

All their property is robbed, although it is under their heads, and they do not realize it.

Every lion is out of its den, all creeping things bite.

Darkness gathers, the land is silent.

The one who made them is set in his horizon.

(But) the land grows bright when you are risen from the horizon,

Shining in the orb in the daytime, you push back the darkness and give forth your rays.

The Two Lands are in a festival of light—

Awake and standing on legs, for you have lifted them up:

Their limbs are cleansed and wearing clothes,

Their arms are in adoration at your appearing.

The whole land, they do their work:

All flocks are content with their pasturage,

Trees and grasses flourish,

Birds are flown from their nests, their wings adoring your Ka;

All small cattle prance upon their legs.

All that fly up and alight, they live when you rise for them.

Ships go downstream, and upstream as well, every road being open at your appearance.

Fish upon the river leap up in front of you, and your rays are within the Great Green (sea).

(excerpted from the Great Hymn to the Aten in the Tomb of Aya, as translated in William J. Murnane, Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt, edited by Edmund S. Meltzer [Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995])

At the same time, Atenism gave the king himself a divine-like role as sole representative and interpreter of the Aten—as stated elsewhere in the above hymn, “there is no one who knows you except your son”—so that any access to and understanding of the god was mediated through the figure of the king and his family. Although there is no reason to think the king’s self-promotion was only politically motivated, the differentiation of king and gods was altered.

The Last Years

Possibly even Akhenaten’s last years and certainly the period after his death give evidence of a troubled succession. Nefertiti, Meritaten, the mysterious pharaoh Smenkhkare, and the female pharaoh Ankhetkhepherure—for whom the chief candidates in discussions so far have been Nefertiti and Meritaten, the eldest daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti—and ultimately Tutankhaten all have roles. Energetic scholarly discussion of the events of this period and the identity, parentage, personal history, and burial place of many members of the Amarna royal family is ongoing. It is clear that already during the succession period, there was some rapprochement with Amun’s adherents at Thebes. With the reign of Tutankhaten / Tutankhamun, the royal court left Akhetaten and returned to Memphis; traditional relations with Thebes were resumed and Amun’s priority fully acknowledged. With Haremhab, Akhenaten’s constructions at Thebes were dismantled, and dismantling began at Amarna. Apparently in the reign of Ramses II, the formal buildings of Akhetaten were completely destroyed, and many of their blocks reused as matrix stone in his constructions at Hermopolis and elsewhere. The site had presumably been abandoned.

Citation: Hill, Marsha. “Art, Architecture, and the City in the Reign of Amenhotep IV / Akhenaten (ca. 1353–1336 B.C.)”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/amar/hd_amar.htm (November 2014)

| Marsha Hill Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

| For more information please view the following links: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/amar/hd_amar.htm |

An Artisan’s Tomb in New Kingdom Egypt

Almost thirty-three centuries ago, a young man named Khonsu became a “servant in the Place of Truth”—a designation that identified members of the crew of artisans who carved and decorated the royal tombs of the New Kingdom. These artisans included quarrymen, scribes (23.3.4), draftsmen (14.108), sculptors, painters, and carpenters. The entire crew, which usually numbered no more than sixty, lived with their families in a walled community known to its residents simply as the Village, a ruin now known as Deir el-Medina. Situated in a small desert valley on the west bank of the Nile, at the edge of the Theban cliffs, the Village was within easy reach of the two principal royal cemeteries: the Great Place, now called the Valley of the Kings; and the Place of Beauty, or the Valley of the Queens.

The same talents that created a spectacular sepulchre for the ruling king were also put to use in the more modest burial places of the workers themselves.

Khonsu was the fourth son in a large family, and like most members of the royal work crew, he and at least one of his brothers had followed in the footsteps of their father, Sennedjem (86.1.10), who was also a servant in the Place of Truth. Sennedjem was an active member of the crew in the time of Menmaatre Seti, the son of a former general named Ramesses who had ascended the throne of Egypt and founded a new dynasty.

Sennedjem and his sons were fortunate to live during a period of great prosperity for the Village. At the height of Sennedjem’s career, in the first sixteen years of the new dynasty, two royal tombs were required. The amount of time it took the crew to complete a royal tomb depended on the length of a king’s reign, and work was sometimes cut short by the pharaoh’s death. Because of the length of time required for mummification, the team would have up to three months to finish its work, and then the process would begin all over again for the new pharaoh.

The same talents that created a spectacular sepulchre for the ruling king were also put to use in the more modest burial places of the workers themselves. Located in a terraced cemetery on the hillside adjacent to the Village, their funerary monuments included small, vaulted, above-ground offering chapels that were topped by miniature, steep-sided pyramids. In or near the chapels, shafts cut deep into the bedrock led to groupings of corridors and vaulted rooms that were often used by many generations of the same family. One of the finest of these tombs belonged to Sennedjem and his descendants. Built at the southern end of the cemetery, the family crypt was just a stone’s throw away from its owner’s house. The upper level of the complex had offering chapels for both Sennedjem and Khonsu, and the decorated burial chamber contained the mummies of Sennedjem and his wife, Iineferti; Khonsu and his wife, Tameket; Khonsu’s younger brother Ramesses; and four other named members of the family, as well as eleven unidentified mummies.

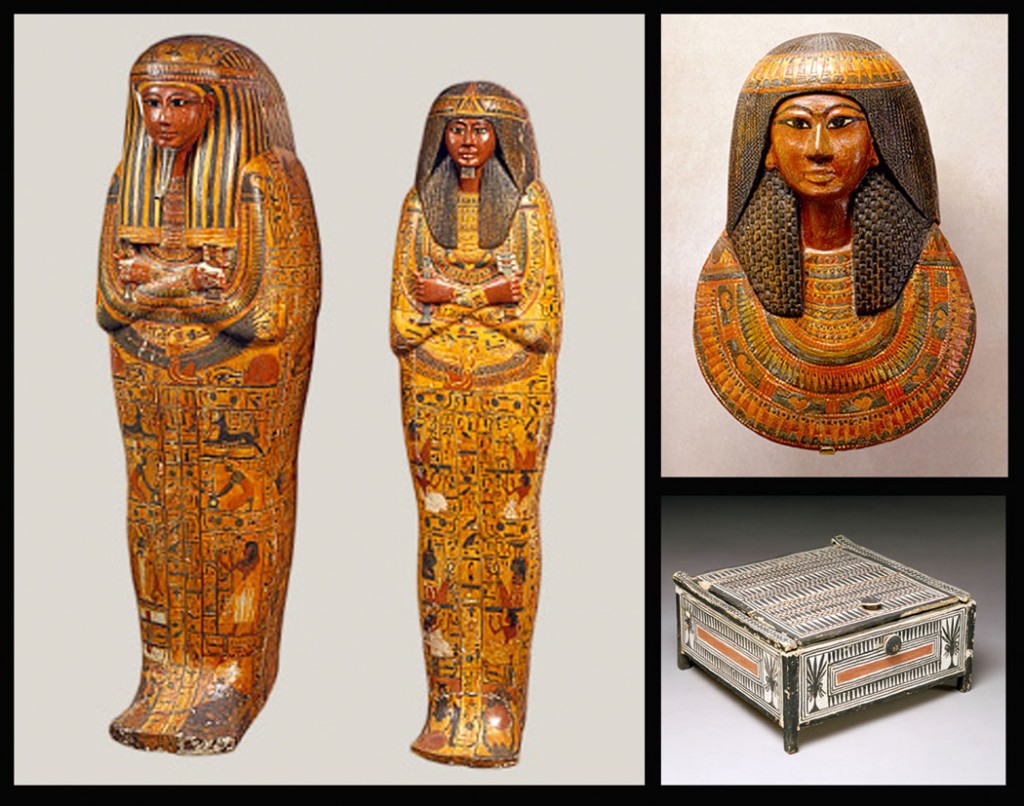

In preparation for his journey to the afterworld, Khonsu commissioned a pair of nesting anthropoid coffins (86.1.1,.2) made of wood. The lid of each depicts Khonsu in the form of a mummy, with arms crossed over his chest and hands clutching the tyet amulet and djed pillar, the same magical symbols that were used some 200 years earlier on Hatnofer’s chair (36.3.152) to ensure the owner’s well-being. The coffins are covered with magical texts and vignettes featuring deities as well as Khonsu and Tameket. A mask of painted wood (86.1.4) and cartonnage completed the ensemble. Khonsu had also obtained a painted canopic box to hold his internal organs and several shawabtis (86.1.14,.18,.21; 67.80; 86.1.128), little figurines that were intended to substitute for the deceased owner if he were called upon to perform any kind of manual labor in the next life (30.4.2).

When he finally began his own journey to the afterworld, Khonsu was about sixty-five years of age and had seen two generations of his descendants enter the work crew. He was placed in the family tomb along with his parents, and the funeral rites were probably performed by his sons Nakhemmut and Nakhtmin, who spoke the words of the offering texts and repeated the names of those who had passed on to the next world, thus giving them renewed life. After being used by many generations of Khonsu’s descendants, the family crypt was sealed at last and remained undisturbed until February 1, 1886, when it was uncovered by agents of the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

| Catharine H. Roehrig Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Citation: Roehrig, Catharine H. “An Artisan’s Tomb in New Kingdom Egypt”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/srvt/hd_srvt.htm (October 2004)

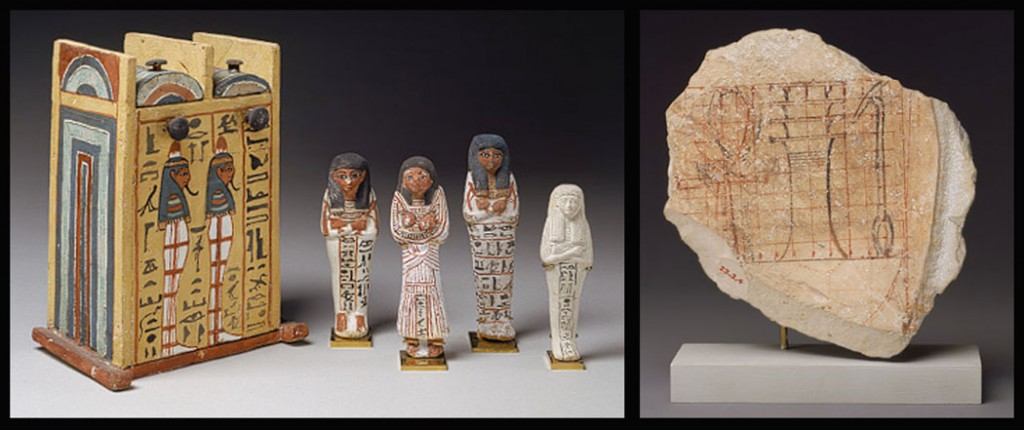

Left: Shawabti box and shawabtis, New Kingdom, reign of Ramesses II, ca. 1279–1213 b.c., Egyptian; From the tomb of Sennedjem, Deir el–Medina, western Thebes. Painted wood; limestone and ink; H. of box 11 1/4 in. (28.5 cm), The wooden shawabti box is inscribed for Paremhab, a servant in the Place of Truth who was a son or grandson of Sennedjem and Iineferti. The shawabti figures, from left to right, are inscribed for Iineferti and her eldest son, Khabekhnet; for Khonsu; for Khabekhnet alone; and for a woman named Mesu. Although Khabekhnet had a separate tomb complex near that of Sennedjem, he is depicted with his siblings in the decoration of Sennedjem’s burial chamber, and objects inscribed with his name were buried in the family tomb.

Left: Shawabti box and shawabtis, New Kingdom, reign of Ramesses II, ca. 1279–1213 b.c., Egyptian; From the tomb of Sennedjem, Deir el–Medina, western Thebes. Painted wood; limestone and ink; H. of box 11 1/4 in. (28.5 cm), The wooden shawabti box is inscribed for Paremhab, a servant in the Place of Truth who was a son or grandson of Sennedjem and Iineferti. The shawabti figures, from left to right, are inscribed for Iineferti and her eldest son, Khabekhnet; for Khonsu; for Khabekhnet alone; and for a woman named Mesu. Although Khabekhnet had a separate tomb complex near that of Sennedjem, he is depicted with his siblings in the decoration of Sennedjem’s burial chamber, and objects inscribed with his name were buried in the family tomb.

Right: Artists gridded sketch, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Hatshepsut, ca. 1479–1458 b.c.,

Egyptian; From western Thebes, Limestone and ink; W. 5 1/2 in. (14 cm). This small sketch depicts a frequently occurring group of hieroglyphs meaning “life, prosperity, and dominion.” The grid lines allowed the artist to draw the hieroglyphs at whatever scale was needed.

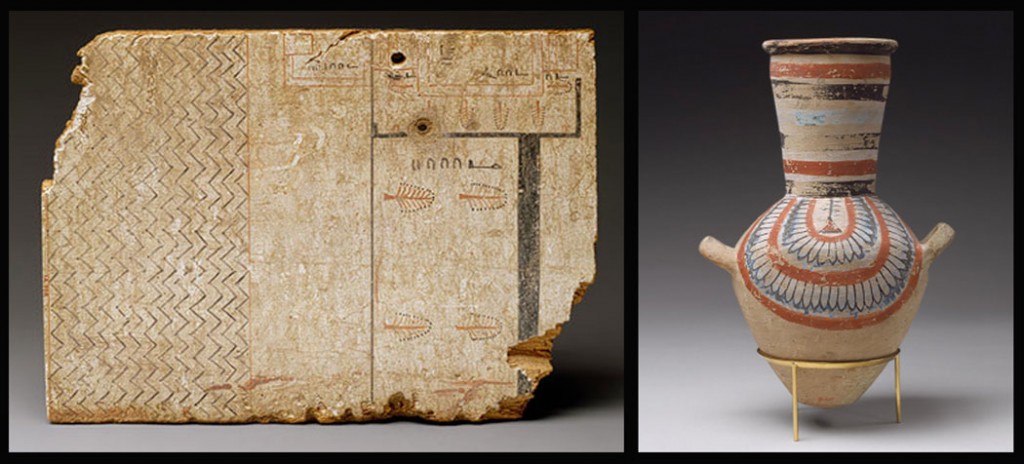

Left: Writing board with an architectural drawing, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, ca. 1550–1295 b.c.,

Left: Writing board with an architectural drawing, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, ca. 1550–1295 b.c.,

Egyptian; From western Thebes, Plastered and painted wood; W. 13 7/8 in. (35.2 cm)

Right: Jar from the tomb of Sennedjem, New Kingdom, reign of Ramesses II, ca. 1279–1213 b.c.,

Egyptian; From the tomb of Sennedjem, Deir el–Medina, western Thebes, Painted red pottery; H. 12 in. (30.5 cm)

Left: Khonsu’s anthropoid coffins, New Kingdom, reign of Ramesses II, ca. 1279–1213 b.c.,

Left: Khonsu’s anthropoid coffins, New Kingdom, reign of Ramesses II, ca. 1279–1213 b.c.,

Egyptian; From the tomb of Sennedjem, Deir el–Medina, western Thebes, Gessoed and painted wood; H. of taller coffin 78 3/4 in. (200 cm)

Right top: Khonsu’s funerary mask, New Kingdom, reign of Ramesses II, ca. 1279–1213 b.c.

Egyptian; From the tomb of Sennedjem, Deir el–Medina, western Thebes,

Painted wood and cartonnage; H. 18 7/8 in. (48 cm)

Right bottom: Box from the tomb of Sennedjem, New Kingdom, reign of Ramesses II, ca. 1279–1213 b.c., Egyptian; From the tomb of Sennedjem, Deir el–Medina, western Thebes,

Gessoed and painted wood; H. 6 1/4 in. (16 cm)

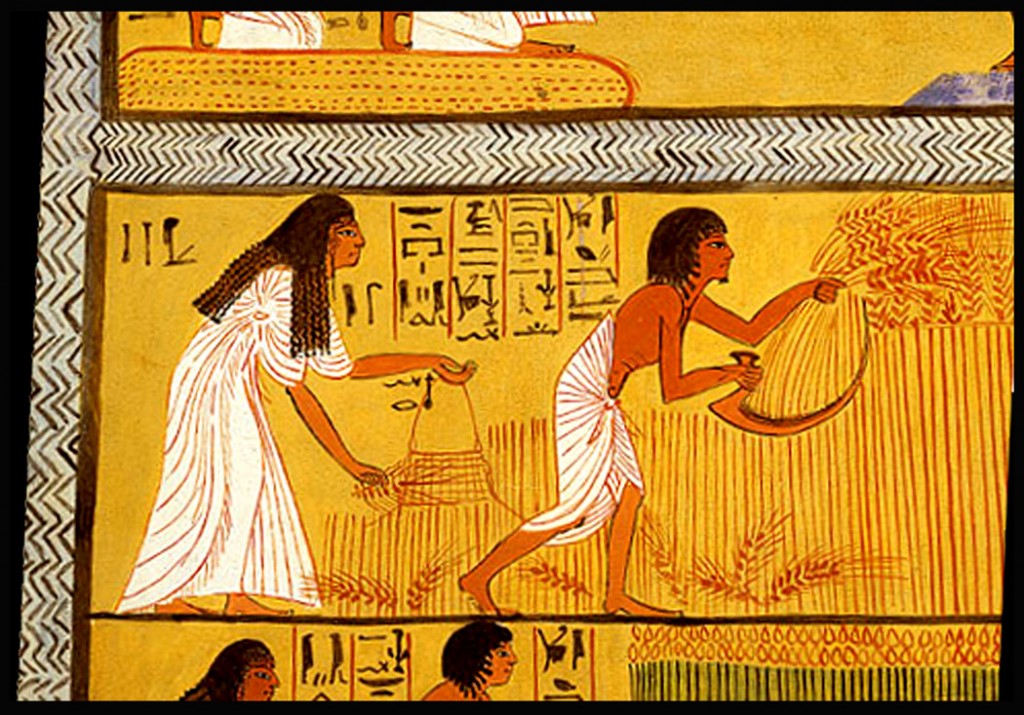

Facsimile of a scene depicting the afterlife (Tomb of Sennedjem) (detail), ca. 1922,

Facsimile of a scene depicting the afterlife (Tomb of Sennedjem) (detail), ca. 1922,

Charles K. Wilkinson (American, born Britain, 1897–1986),

Tempera on paper; H. 54 in. (137.2 cm), The east wall of Sennedjem’s vaulted crypt is decorated with a vignette that illustrates spell number 110 in the Book of the Dead. Here, in a photograph taken at the site, Sennedjem and Iineferti are shown harvesting grain, sowing seeds, and pulling flax in the abundant fields of the next world.

For more information please view the following links: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/srvt/hd_srvt.htm

Egypt in the Late Period (ca. 712–332 B.C.)

1. Kushite Pharaoh, Late Period, Dynasty 25, ca. 713–664 b.c., Egyptian,

Bronze with gilding; H. 3 in. (7.5 cm)

2. Statuette of a Kushite Priest, Adapted for a King, late Dynasty 25, ca. 700–664 b.c., Egyptian, Leaded bronze, precious metal leaf ,8 1/4 in. (21 cm)

3. enat of Taharqo, Late Period, Dynasty 25, reign of Taharqo, ca. 690–664 b.c., Egyptian,

Faience; H. 3 3/4 in. (9.5 cm), Bequest of W. Gedney Beatty, 1941 (41.160.104)

4. Statuette of a Woman, Late Period, Dynasty 26, reign of Necho II, ca. 610–595 b.c.,

Egyptian, Silver; H. 9 1/2 in. (24 cm)

5. Ritual figure, 4th century b.c.–early Ptolemaic Period (380–246 b.c.), Egyptian,

Wood, formerly clad in lead sheet; H. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm), W. 5 5/8 in. (14.3 cm)

6. Cat, Ptolemaic Period, ca. 400–30 b.c., Egyptian, Bronze; H. 11 in. (27.9 cm)

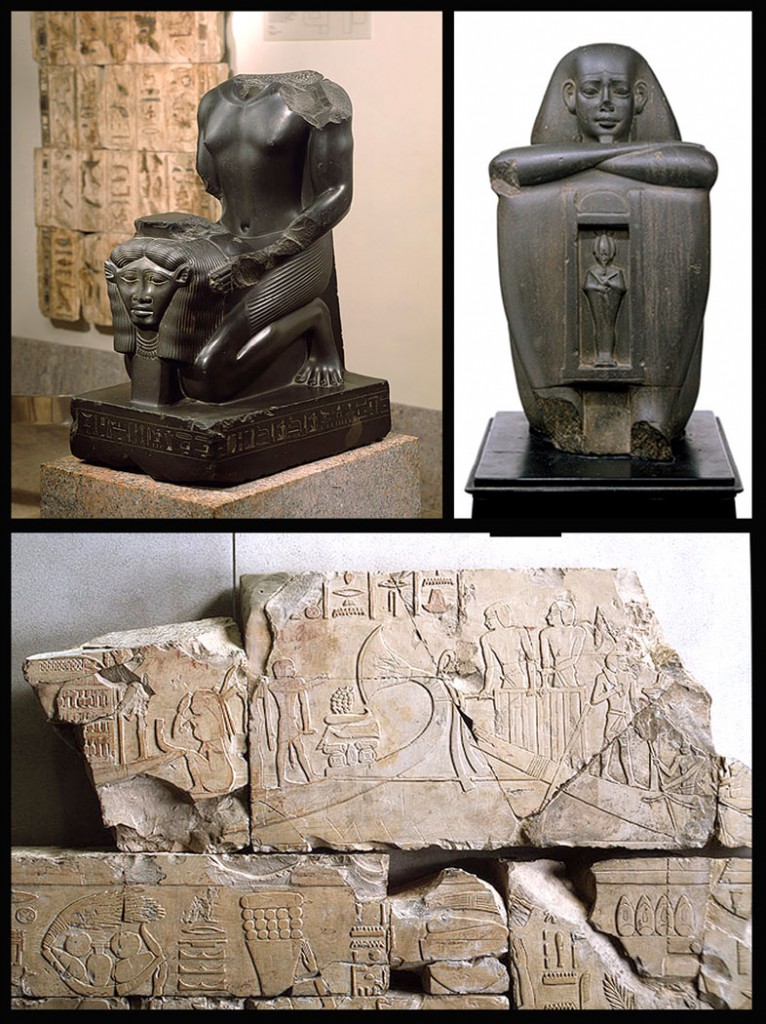

Top left: Kneeling statue of Amenemope–em–hat, Late Period, Dynasty 26, reign of Psamtik I, ca. 664–610 b.c., Egyptian; Apparently from Memphis, Ptah temple, Graywacke; H. including base 25 1/4 in. (64 cm)

Top left: Kneeling statue of Amenemope–em–hat, Late Period, Dynasty 26, reign of Psamtik I, ca. 664–610 b.c., Egyptian; Apparently from Memphis, Ptah temple, Graywacke; H. including base 25 1/4 in. (64 cm)

Top right: Block statue of a governor, Late Period, Dynasty 26 (ca. 664–525 b.c.), Egyptian,

Graywacke; 14 in. (30.5 cm)

Bottom: Reliefs from the Tomb of Nes–peka–shuty, Late Period, early Dynasty 26, late reign of Psamtik I, ca. 656–610 b.c., Egyptian; Deir el–Bahri, western Thebes, Limestone; 13 3/4 x 22 1/2 in. (35 x 57 cm)

1. Ram’s–head amulet, Late Period, Dynasty 25, ca. 712–657 b.c.,

1. Ram’s–head amulet, Late Period, Dynasty 25, ca. 712–657 b.c.,

Egyptian/Nubian, Gold; 1 5/8 x 1 3/8 in. (4.2 x 3.6 cm)

2. Cosmetic container in the form of a Bes image holding the cap of a kohl tube, Late Period, Dynasty 27, ca. 525–404 b.c., Egyptian, Faience; H. 3 5/8 in. (9.2 cm), W. 1 3/4 in. (4.4 cm)

3. Inlays and shrine elements, Dynasty 30–Ptolemaic Period, ca. 380–30 b.c., Egyptian,

Glass; H. (each drum) 1 5/8 in. (4.1 cm)

4. Bark Sphinx (Sib), Dynasty 26, ca. 664–525 b.c., Egyptian, Leaded bronze, 8 1/2 in. x 6 1/4 in. (21.5 cm x 16 cm)

5. Head of a Priest, 4th century b.c., Egyptian,

Basalt; H. 8 3/8 in. (21.2 cm), W. 5 3/4 in. (14.5 cm)

1. Head of the pharaoh Apries, Late Period, Dynasty 26, reign of Apries, ca. 589–570 b.c., Egyptian,

1. Head of the pharaoh Apries, Late Period, Dynasty 26, reign of Apries, ca. 589–570 b.c., Egyptian,

Diorite; H. 11 15/16 in. (30.3 cm)

2. Statuette of the goddess Taweret, Ptolemaic Period, ca. 332–30 b.c., Egyptian,

Glassy faience; H. 4 1/4 in. (10.8 cm)

3. Statuette of the god Anubis as embalmer, Ptolemaic Period, ca. 332–30 b.c., Egyptian,

Wood with gesso and paint; H. 16 1/2 in. (42 cm)

4. Statuette of Isis and Horus, Ptolemaic Period, ca. 304–30 b.c., Egyptian,

Egyptian faience; H. 6 3/4 in. (17 cm)

5. Statue of the falcon god Horus with Nectanebo II, Late Period, Dynasty 30, reign of Nectanebo II, ca. 360–343 b.c., Egyptian, Basalt; H. 28 1/4 in. (72 cm)

6. Torso of a striding statue of a general, 4th century b.c., Egyptian, Schist; H. 27 1/4 in. (69.2 cm)

7. Head attributed to Arsinoe II, Ptolemaic Period, reign of Arsinoe II, ca. 278–270 b.c.,

Egyptian; From Abu Roash, Indurated limestone; H. 4 5/8 in. (11.8 cm)

8. Head of an Antelope, Late Period, Dynasty 27, ca. 525–404 b.c., Egyptian,

Greywacke, agate, Egyptian alabaster; H. 3 1/2 in. (9 cm)

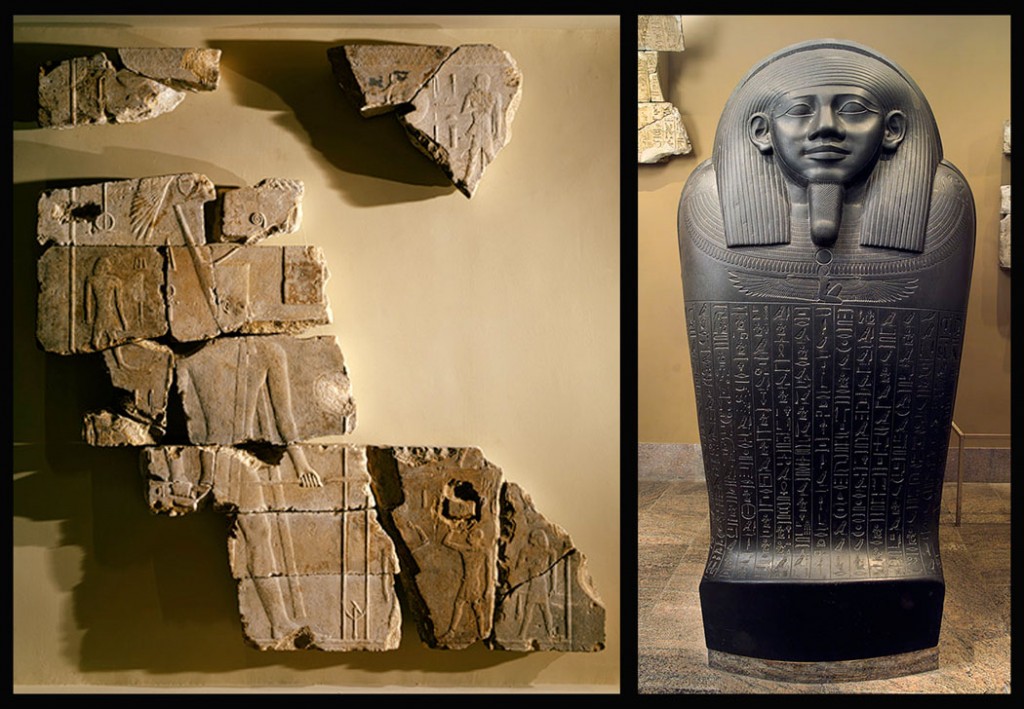

Left: Relief of Apries, Late Period, Dynasty 26, reign of Apries, ca. 589–570 b.c., Egyptian, Limestone

Left: Relief of Apries, Late Period, Dynasty 26, reign of Apries, ca. 589–570 b.c., Egyptian, Limestone

Right: Sarcophagus of Horkhebit, Late Period, Dynasty 26, ca. 590 b.c., Egyptian; From Saqqara,

Basalt; L. 8 ft. 4 in. (2.55 m), W. 4 ft. (1.21 m)

Kushite Period, or Dynasty 25 (ca. 712–664 B.C.)

From ca. 728 to 656 B.C., the Nubian kings of Dynasty 25 dominated Egypt. Like the Libyans before them, they governed as Egyptian pharaohs. Their control was strongest in the south. In the north, Tefnakht’s successor, Bakenrenef, ruled for four years (ca. 717–713 B.C.) at Sais until Piankhy’s successor, Shabaqo (ca. 712–698 B.C.), overthrew him and established Nubian control over the entire country. The accession of Shabaqo can be considered the end of the Third Intermediate Period and the beginning of the Late Period in Egypt.

During the Late Period, the reemergence of a centralized royal tradition that interacted with the relatively decentralized network inherited from the Third Intermediate Period created a rich artistic atmosphere.

Nubian rule, which viewed itself as restoring the true traditions of Egypt, benefited Egypt economically and was accompanied by a revival in temple building and the arts that continued throughout the Late Period. At the same time, however, the country faced a growing threat from the Assyrian empire to its east. After forty years of relative security, Nubian control—and Egypt’s peace—were broken by an Assyrian invasion in ca. 671 B.C. The current pharaoh, Taharqo (ca. 690–664 B.C.), retreated south and the Assyrians established a number of local vassals to rule in their stead in the Delta. One of them, Necho I of Sais (ca. 672–664 B.C.), is recognized as the founder of the separate Dynasty 26. For the next eight years, Egypt was the battleground between Nubia and Assyria. A brutal Assyrian invasion in 663 B.C. finally ended Nubian control of the country. The last pharaoh of Dynasty 25, Tanutamani (664–653 B.C.), retreated to Napata. There, in relative isolation, he and his descendants continued to rule Nubia, eventually becoming the Meroitic civilization, which flourished in Nubia until the fourth century A.D.

Saite Period, or Dynasty 26 (664–525 B.C.)

When the Assyrians withdrew after their final invasion, Egypt was left in the hands of the Saite kings, though it was actually only in 656 B.C. that the Saite king Psamtik I was able to reassert control over the southern area of the country dominated by Thebes. For the next 130 years, Egypt was able to enjoy the benefits of rule by a single strong, native family, Dynasty 26. Elevated to power by the invading Assyrians, Dynasty 26 faced a world in which Egypt was no longer concerned with its role in international power politics but with its sheer survival as a nation. The Egyptians, however, still chose to think of their land as self-contained and free from external influence, unchanged from the days of the pyramid builders 2,000 years earlier. In deference to this ideal, the Saite pharaohs deliberately adopted much from the culture of earlier periods, particularly the Old Kingdom, as the model for their own. Later generations would remember this dynasty as the last truly Egyptian period and would, in turn, recapitulate Saite forms.

Under Saite rule, Egypt grew from a vassal of Assyria to an independent ally. There were even echoes of the bygone might of Egypt’s New Kingdom in Saite military campaigns into Asia Minor (after the collapse of the Assyrian empire in 612 B.C.) and Nubia. In pursuit of these goals, however, the Saite pharaohs had to rely on foreign mercenaries—Carian (from southwestern Asia Minor, modern Turkey), Phoenician, and Greek—as well as Egyptian soldiers. These different ethnic groups lived in their own quarters of the capital city, Memphis. The Greeks were also allowed to establish a trading settlement at Naukratis in the western Delta. This served as a conduit for cultural influences traveling from Egypt to Greece.

After the fall of Assyria in 612 B.C., the major foreign threat to Egypt came from the Babylonians. Although Babylonia had invaded Egypt in 568 B.C. during a brief civil war, both countries formed a mutual alliance in 547 B.C. against the rising threat of a third power, the Persian empire—but to no avail. The Persians conquered Babylonia in 539 B.C. and Egypt in 525 B.C., bringing an end to the Saite dynasty and native control of Egypt.

Persian Period, or Dynasty 27 (525–404 B.C.)

Egypt’s new Persian overlords adopted the traditional title of pharaoh, but unlike the Libyans and Nubians, they ruled as foreigners rather than Egyptians. For the first time in its 2,500-year history as a nation, Egypt was no longer independent. Though recognized as an Egyptian dynasty, Dynasty 27, the Persians ruled through a resident governor, called a satrap, helped by local native chiefs. Persian domination actually benefited Egypt under Darius I (521–486 B.C.), who built temples and public works, reformed the legal system, and strengthened the economy. The military defeat of Persia by the Greeks at Marathon in 490 B.C., however, inspired resistance in Egypt; and for nearly a century thereafter, Persian control was challenged by a series of local Egyptian kings, primarily in the Delta.

Dynasties 28–30 (404–343 B.C.)

In 404 B.C., a coalition of these rulers succeeded in overthrowing their Persian masters. From 404 to 399 B.C., Egypt seems to have been ruled by Amyrtaios II of Sais, who is traditionally recognized as the only pharaoh of Dynasty 28. Control then passed for twenty years (399–380 B.C.) to Dynasty 29, in the eastern Delta city of Mendes, and finally to Dynasty 30, in the mid-Delta city of Sebennytos.

The first king of Dynasty 30, Nectanebo I (380–362 B.C.), managed to repel a Persian attack shortly after he ascended the throne. The remaining years of his reign were fairly peaceful and were marked by an ambitious program of temple construction, which was continued on an even grander scale by Nectanebo II (360–343 B.C.). The latter king managed to hold off another Persian attack in 351 B.C., but in 343 B.C. a third attack succeeded, and Egypt fell once again to the Persians, who were defeated in turn by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. These final invasions were the death blow to Egyptian control of their own country. Nectanebo’s dynasty is recognized as the last in ancient Egyptian history, and Nectanebo II became the last Egyptian to rule in Egypt for the next 2,500 years.

Art and Culture

During the Late Period, the reemergence of a centralized royal tradition that interacted with the relatively decentralized network inherited from the Third Intermediate Period created a rich artistic atmosphere.

Particularly among royal artworks, it is possible to speak of marked affinities for models from certain anterior periods: Kushite kings admired Old Kingdom models, Saite kings those of the Old and New Kingdoms, and later kings of Dynasty 30 looked back beyond the Persian interlud to the kings of late Dynasty 26. Viewed from the perspective of metal statuary produced in temples or of nonroyal artworks, however, stylistic patterns suggest a complex interplay of influences less hierarchically determined by the temporal power of the king than in previous periods, with the result that the choices of patrons and artists are more recognizable.

A taste for realistic modeling of features of nonroyal persons emerges, while attention to the naturalistic modeling of flesh and bone in human and animal sculpture reaches new heights.

While precious metal and bronze statuary and equipment had long associations with temple cult and ritual, by the first millennium B.C. changes in beliefs and practices had come about. A broad range of individuals made temple offerings, including relatively valuable bronze statuettes and equipment. While the king made offerings in his role as mediator between the gods and mankind, for private donors the goal was attainment of eternal life, for which the personal favor of or physical proximity to a deity was now believed to be as or even more efficacious than tombs and mortuary cult provisions. Osiris and the flourishing cults of animal avatars of certain gods were particular beneficiaries of these new offering practices.

| Following the period of Persian rule, the kings of Dynasties 28 through 30 brought a new focus to their role as maintainers of a long tradition. Prodigious temple building and major production of statuary enacted an impressive reformulation and promulgation of the concept of divine kingship and formalized many other aspects of Egypt’s ancient artistic and religious traditions in the face of threatening outside powers. |

Marsha Hill

Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of ArtJames Allen

Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

For more information please view the following links: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/lapd/hd_lapd.htm

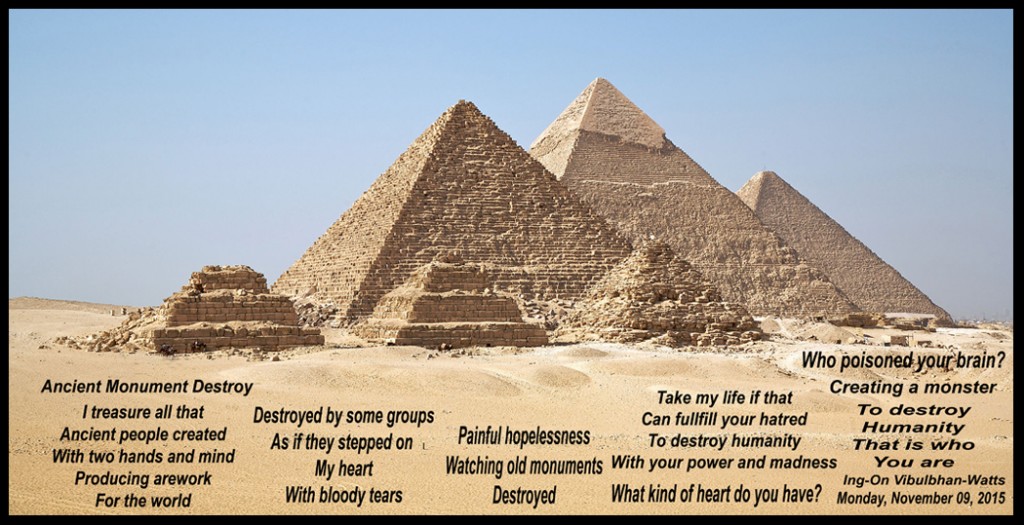

All Gizah Pyramids and Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts’ Poem “Ancient Monument Destroy”

All Gizah Pyramids and Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts’ Poem “Ancient Monument Destroy”

Leave a Reply