Amiri Baraka

Remember the Writer and Poet

Native of Newark, New Jersey, U.S.A.

Passed Away on Thursday, January 9th, 2014

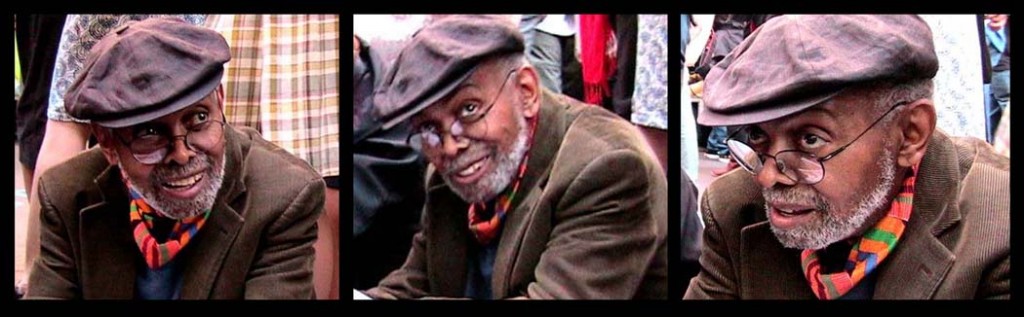

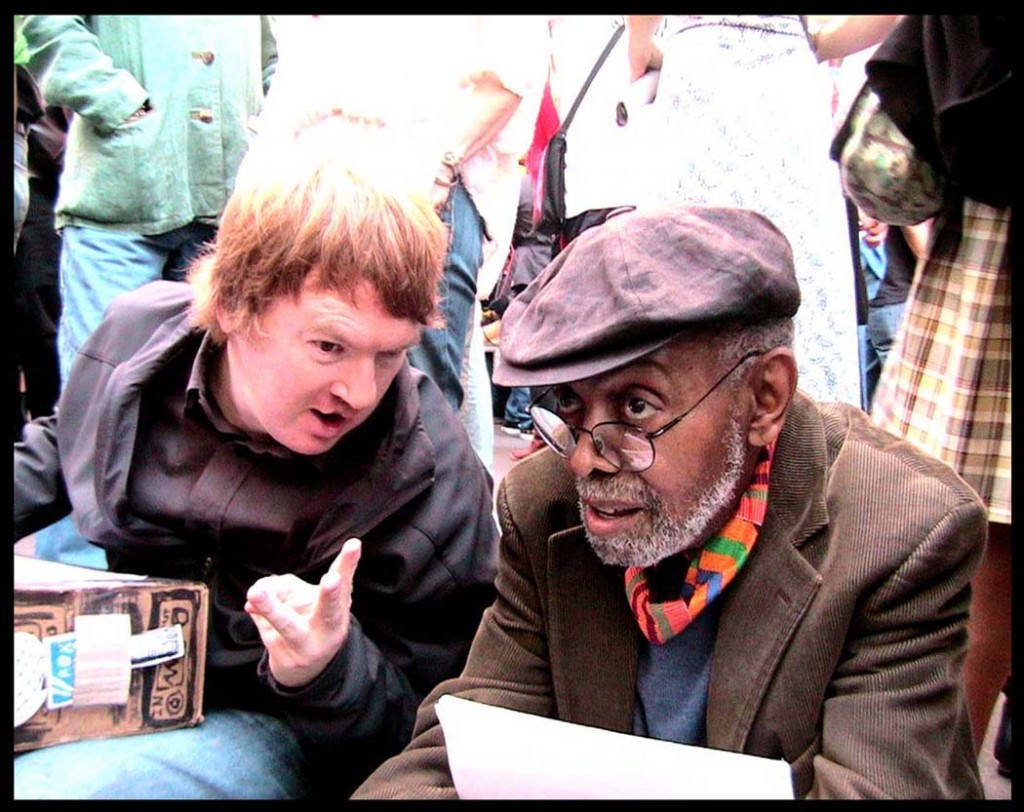

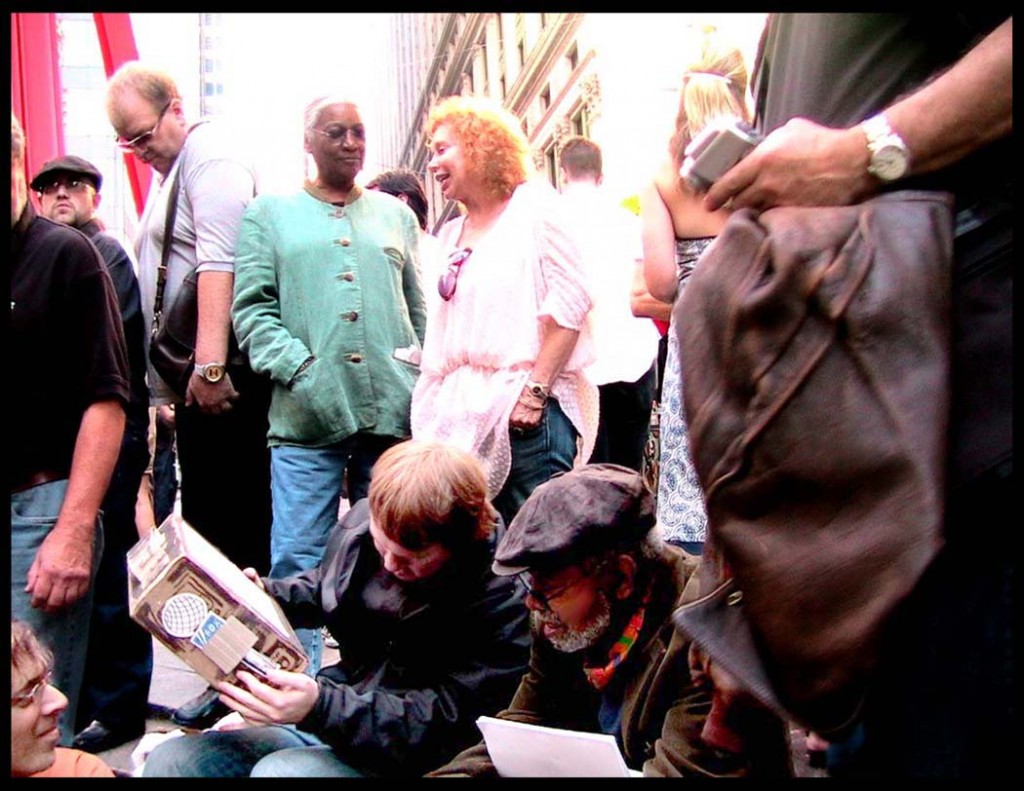

John and I were lucky to see him

And I took pictures of him and his wife

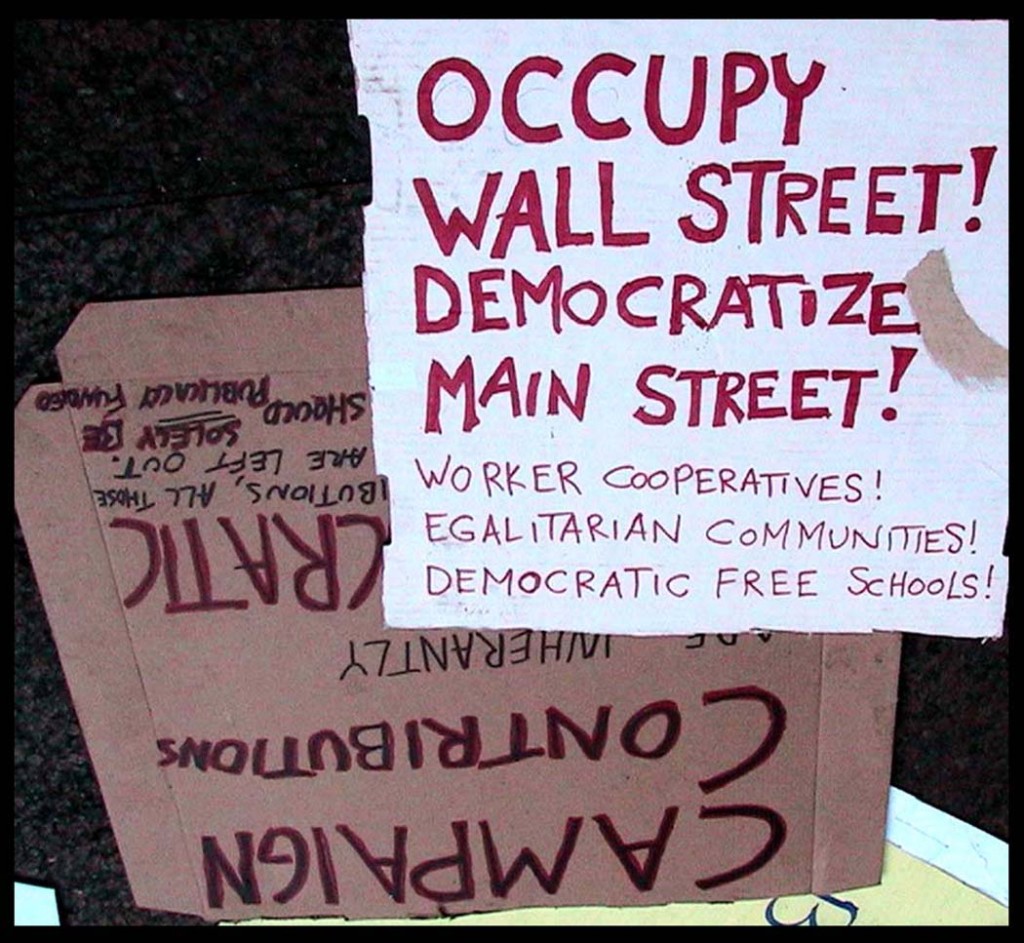

At the demonstration of Occupy Wall Street

Zuccotti Park, New York City

On Sunday, October 9th, 2011

Losing a Friend

My heart sank

When we heard

Amiri Baraka

The poet of Newark

Passed away

My dear friend

We know you more

Than you knew

So glad seeing you

Stepping in our shop

Choosing Silver earrings

For the wife

He said

Late night back from NYC in our car

Oh, that’s Mr. Baraka!

I tell John

Pointing to the sidewalk on Market St.

Where he walks with a young man

We saw him

Here and there

Near and far

Admiring his works

His fighting spirit

Fighter he was

Among the good and the bad

Black and White

Young and old

And for the gangs of Newark kids

Who never knew his words

Writings and talking

That’s what he did best

Left are the words he composed

No one will forget

Amiri Baraka

Everett LeRoi Jones

He made his mark

Now and then

Here and beyond

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Tuesday, January 14, 2014, 2:57 am

On Sunday, October 9, 2011 John and I went to Zuccotti Park, NYC, visiting the Occupy Wall Street protest. We walked about observing and taking as many photographs as we could as a remembrance of the event. We saw Mr. Amiri Baraka sitting on the steps talking with some young people. John greeted him and joined in the conversation. He looked at me with his large big eyes to greet me. I took advantage to take his picture. I spotted his wife, Amina Baraka near by talking to a lady. It was a very nice and exceptional surprise for us to see him at the event. The following are some photographs and information about Mr. Amiri Baraka.

Mrs. Amina Baraka in a green blouse (Amiri Baraka’s wife)

Few years ago, a lady came in our shop, looked around then spotted a bunch of dried small white flowers in John’s large ceramic pot. She picked up a bunch of dried flowers asking me how much they cost. I told her that they are flowers from our backyard garden. I said you can have them for free. She thanked me, took a bunch of dried small white flowers and left.

A few months later Mr. Baraka came in our shop with a lady. He introduced us to his wife. I said, “Did I see you before?” She replied, “Yes, you gave me a bunch of dried flowers.”

The Agitator is Gone

Life long agitator

His time spent

Stirring the water and oil

Asking for smoothness

Equality for all

Hard work

Hard life

Learning

Seeing

Affecting his poor soul

Fighting harder

Stirred by knowledge

Religion changes

Everett LeRoi Jones

Becomes Amiri Baraka

Ideologies

Democracy

Capitalism

Socialism

Communism

Marxism

Stirring in his cranium

Giving out all

Lecturing

Writings

Performing his poems

With all his heart and soul

Still stirring

Harder he tries

Voicing out

All he knows

Exhausted old man

Last breath

Wishing

Equality

And justice for all

Closing his sparkling large eyes

Finding peace at last

Forever sleep

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Tuesday, January 14, 2014, 12:40 am

Everett Leroy Jones was born in Newark on Oct. 7, 1934. His father, Coyette, was a postal supervisor; his mother, the former Anna Russ, was a social worker. Growing up, young Leroy, as he was known, took piano, drum and trumpet lessons — a background that would inform his later work as a jazz writer — and also studied drawing and painting.

He attended Barringer High School. He won a scholarship to Rutgers University in 1951, but a continuing sense of cultural dislocation prompted him to transfer in 1952 to Howard University, which he left without obtaining a degree. During this period, partly in homage to the African-American journalist Roi Ottley (1906-60), he changed the spelling of his name to LeRoi, with the emphasis on the second syllable.

His major fields of study were philosophy and religion. Baraka subsequently studied at Columbia University and the New School for Social Research without obtaining a degree.

Though by all accounts a brilliant student, he came to regard the university’s emphasis on upward mobility for blacks as distastefully assimilationist — “an employment agency” where “they teach you to pretend to be white,” he later called it. Losing interest in his classes, he was expelled before graduating.

In 1954, he joined the US Air Force as a gunner, reaching the rank of sergeant. After an anonymous letter to his commanding officer accusing him of being a communist led to the discovery of Soviet writings, Baraka was put on gardening duty. After three years, dishonorable discharge for violation of his oath of duty. Some of his reading material had made the Air Force suspect that he was a Communist. The irony, he later said, was that he did become a Communist, but not until long afterward.

It was the worst period of my life,” Mr. Baraka told Essence magazine in 1985. “I finally found out what it was like to be disconnected from family and friends. I found out what it was like to be under the direct jurisdiction of people who hated black people. I had never known that directly.”

To stave off loneliness and misery, he read widely and deeply, stocking the library on his base in Puerto Rico with books — philosophy, literary fiction, left-wing history — the likes of which it had almost certainly never seen.

He moved to New York, where he took an editorial job on a music magazine, The Record Changer, and settled in Greenwich Villageamid the heady atmosphere of the Beat poets.

He be friended their dean, Allen Ginsberg, to whom, in the puckish spirit of the times, he had written a letter on toilet paper reading, “Are you for real?” (“I’m for real, but I’m tired of being Allen Ginsberg,” came the reply, on what, its recipient would note with amusement, was “a better piece of toilet paper.”)

In 1967, he adopted the Muslim name Imamu Amear Baraka, which he later changed to Amiri Baraka. He was an American writer of poetry, drama, fiction, essays and music criticism. He was the author of numerous books of poetry and taught at a number of universities, including the State University of New York at Buffalo and the State University of New York at Stony Brook. He received the PEN Open Book Award, formerly known as the Beyond Margins Award, in 2008 for Tales of the Out and the Gone.[2]

Baraka’s poetry and writing has attracted both extreme praise and condemnation. Within the African-American community, some compare him to James Baldwin and call Baraka one of the most respected and most widely published Black writers of his generation.[3] Others have said his work is an expression of violence, misogyny, homophobia and racism.[4] Baraka’s brief tenure as Poet Laureate of New Jersey (2002–03), involved controversy over a public reading of his poem “Somebody Blew Up America?” and accusations of anti-semitism, and some negative attention from critics, and politicians[5][6]

The same year, he moved to Greenwich Village working initially in a warehouse for music records. His interest in jazz began during this period. At the same time he came into contact with avant-garde Beat Generation, Black Mountain poets and New York School

New York School poets. In 1958 he married Hettie Cohen, with whom he had two daughters, Kellie Jones (b. 1959) and Lisa Jones (b.1961). They also jointly founded a quarterly literary magazine Yugen, which ran for eight issues (1958–62).[9] Baraka also worked as editor and critic for the literary and arts journal Kulchur (1960–65). With Diane di Prima he edited the first twenty-five issues (1961–63) of their little magazine The Floating Bear.[10] In the autumn of 1961 he co-founded the New York Poets Theatre with di Prima, choreographers Fred Herko and James Waring, and actor Alan S. Marlowe. He had an extramarital affair with Diane di Prima for several years; their daughter, Dominique di Prima, was born in June 1962.

He and Hettie founded Totem Press, which published such Beat icons as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg.[8] In 1961 issued his first collection of verse, “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note.” In the volume’s title poem, he wrote:

Nobody sings anymore.

And then last night, I tiptoed up

To my daughter’s room and heard her

Talking to someone, and when I opened

The door, there was no one there …

Only she on her knees, peeking into

Her own clasped hands.

Baraka visited Cubain July 1960 with a Fair Play for Cuba Committee delegation and reported his impressions in his essay “Cuba libre”.[11] In 1961 Baraka co-authored a Declaration of Conscience in support of Fidel Castro‘s regime.[12] Baraka also was a member of the Umbra Poets Workshop of emerging Black Nationalist writers (Ishmael Reed, and Lorenzo Thomas among others) on the Lower East Side (1962–65). In 1961 a first book of poems, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note, was published. Baraka’s article “The Myth of a ‘Negro Literature’” (1962) stated that “a Negro literature, to be a legitimate product of the Negro experience in America, must get at that experience in exactly the terms America has proposed for it in its most ruthless identity.” He also states in the same work that as an element of American culture, the Negro was entirely misunderstood by Americans. The reason for this misunderstanding and for the lack of black literature of merit was according to Jones:

“In most cases the Negroes who found themselves in a position to pursue some art, especially the art of literature, have been members of the Negro middle class, a group that has always gone out of its way to cultivate any mediocrity, as long as that mediocrity was guaranteed to prove to America, and recently to the world at large, that they were not really who they were, i.e., Negroes.”

As long as the black writer was obsessed with being an accepted, middle class, Baraka wrote, he would never be able to speak his mind, and that would always lead to failure. Baraka felt that America only made room for only white obfuscators, not black ones.[13]

Baraka’s Blues People: Negro Music in White America (1963) is a volume of jazz criticism, especially relating to the beginning of the free jazz movement. His acclaimed, but controversial play Dutchman premiered in 1964 and received an Obie Award the same year.

After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, Baraka left his wife and their two children and moved to Harlem. Now a “black cultural nationalist,” he broke away from the predominantly white Beats and became very critical of the pacifist and integrationist Civil Rights movement. His revolutionary poetry now became more controversial.[14] A poem such as “Black Art” (1965), according to academic Werner Sollors from Harvard University, expressed his need to commit the violence required to “establish a Black World.”[15] “Black Art” quickly became the major poetic manifesto of the Black Arts Literary Movement and in it, Jones declaimed “we want poems that kill,” which coincided with the rise of armed self-defense and slogans such as “Arm yourself or harm yourself” that promoted confrontation with the white power structure.[3] Rather than use poetry as an escapist mechanism, Baraka saw poetry as a weapon of action.[16] His poetry demanded violence against those he felt were responsible for an unjust society.

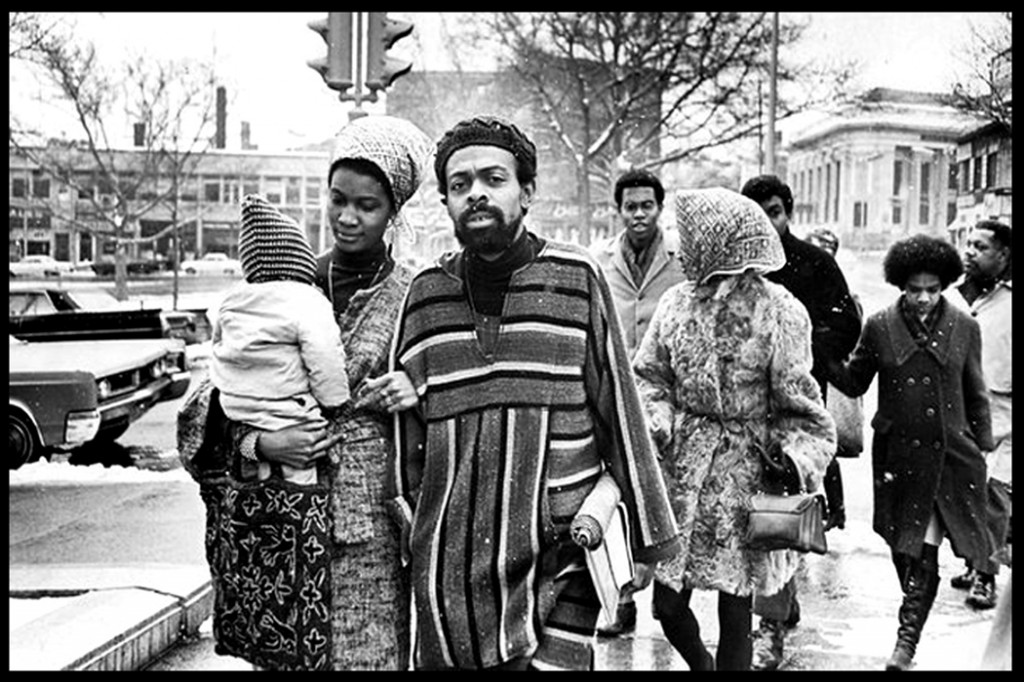

In 1966, Baraka married his second wife, Sylvia Robinson, who later adopted the name Amina Baraka.[17] In 1967, he lectured at San Francisco State University. The year after, he was arrested in Newark for having allegedly carried an illegal weapon and resisting arrest during the 1967 Newark riots, and was subsequently sentenced to three years in prison. Shortly afterward an appeals court reversed the sentence based on his defense by attorney, Raymond A. Brown.[18] Not long after the 1967 riots, Baraka generated controversy when he went on the radio with a Newark police captain and Anthony Imperiale, a Politician and private business owner, and the three of them blamed the riots on “white-led, so-called radical groups” and “Communists and the Trotskyite persons.”[19] That same year his second book of jazz criticism, Black Music, came out, a collection of previously published music journalism, including the seminal Apple Cores columns from Down Beat magazine.

In 1967, Baraka (still Leroi Jones) visited Maulana Karenga in Los Angeles and became an advocate of his philosophy of Kawaida, a multifaceted, categorized activist philosophy that produced the “Nguzo Saba,” Kwanzaa, and an emphasis on African names.[3] It was at this time that he adopted the name Imamu Amear Baraka.[1] Imamu is a Swahili title for “spiritual leader” in which is derived from Arabic word Imam (????). According to Shaw, he dropped the honorific Imamu and eventually changed Amear (which means “Prince”) to Amiri.[1] Baraka means “blessing, in the sense of divine favor.”[1] In 1970 he strongly supported Kenneth A. Gibson‘s candidacy for mayor of Newark; Gibson was elected the city’s first Afro-American Mayor. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Baraka courted controversy by penning some strongly anti-Jewish poems and articles, similar to the stance at that time of the Nation of Islam.[citation needed]

Baraka’s separation from the Black Arts Movement began because he saw certain black writers – capitulationists, as he called them – countering the Black Arts Movement that he created. He believed that the groundbreakers in the Black Arts Movement were doing something that was new, needed, useful, and black, and those who did not want to see a promotion of black expression were “appointed” to the scene to damage the movement.[13] Around 1974, Baraka distanced himself from Black nationalism and became a Marxist and a supporter of third-world liberation movements. In 1979 he became a lecturer in Stony Brook University‘s Africana Studies Department.[citation needed] The same year, after altercations with his wife, he was sentenced to a short period of compulsory community service. Around this time he began writing his autobiography. In 1980 he denounced his former anti-semitic utterances, declaring himself an anti-zionist.[citation needed]

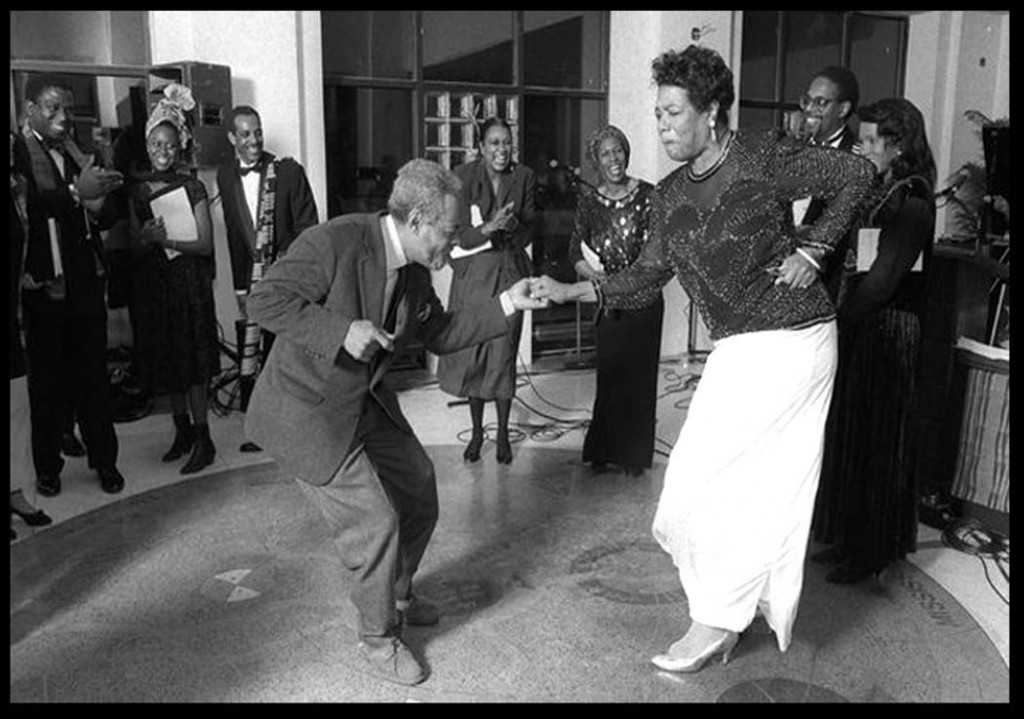

During the 1982–83 academic year, Baraka was a visiting professor at Columbia University, where he taught a course entitled “Black Women and Their Fictions.” In 1984 he became a full professor at Rutgers University, but was subsequently denied tenure.[20] In 1985, Baraka returned to Stony Brook, eventually becoming professor emeritus of African Studies. In 1987, together with Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison, he was a speaker at the commemoration ceremony for James Baldwin. In 1989 Baraka won an American Book Award for his works as well as a Langston Hughes Award. In 1990 he co-authored the autobiography of Quincy Jones, and 1998 was a supporting actor in Warren Beatty‘s film Bulworth. In 1996, Baraka contributed to the AIDS benefit album Offbeat: A Red Hot Soundtrip produced by the Red Hot Organization.

In July 2002, Baraka was named Poet Laureate of New Jersey by Governor Jim McGreevey. Baraka held the post for a year mired in controversy and after substantial political pressure and public outrage demanding his resignation. During the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival in Stanhope, New Jersey, Baraka read his 2001 poem on the September 11th attacks “Somebody Blew Up America?”, which was criticized for anti-Semitism and attacks on public figures. Because there was no mechanism in the law to remove Baraka from the post, the position of state poet laureate was officially abolished by the State Legislature and Governor McGreevey.

Baraka collaborated with hip-hop group The Roots on the song “Something in the Way of Things (In Town)” on their 2002 album Phrenology.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Amiri Baraka on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[21]

In 2003, Baraka’s daughter Shani, aged 31, and her lesbian partner, Rayshon Homes, were murdered in the home of Shani’s sister, Wanda Wilson Pasha, by Pasha’s ex-husband, James Coleman.[22][23] Prosecutors argued that Coleman shot Shani because she had helped her sister separate from her husband.[24] A New Jersey jury found Coleman (also known as Ibn El-Amin Pasha) guilty of murdering Shani Baraka and Rayshon Holmes, and he was sentenced to 168 years in prison for the 2003 shooting.[25]

Amiri Baraka died on January 9, 2014, at Beth Israel Medical Center in Newark, New Jersey, after being hospitalized in the facility’s intensive care unit for one month prior to his death. The cause of death was not reported, but it is mentioned that Baraka had a long struggle with diabetes.[26]

In addition to his wife and his son Ras, survivors include three other sons, Obalaji, Amiri Jr. and Ahi; four daughters, Dominique DiPrima, Lisa Jones Brown, Kellie Jones and Maria Jones; and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Please visit the following link for more information:

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amiri_Baraka

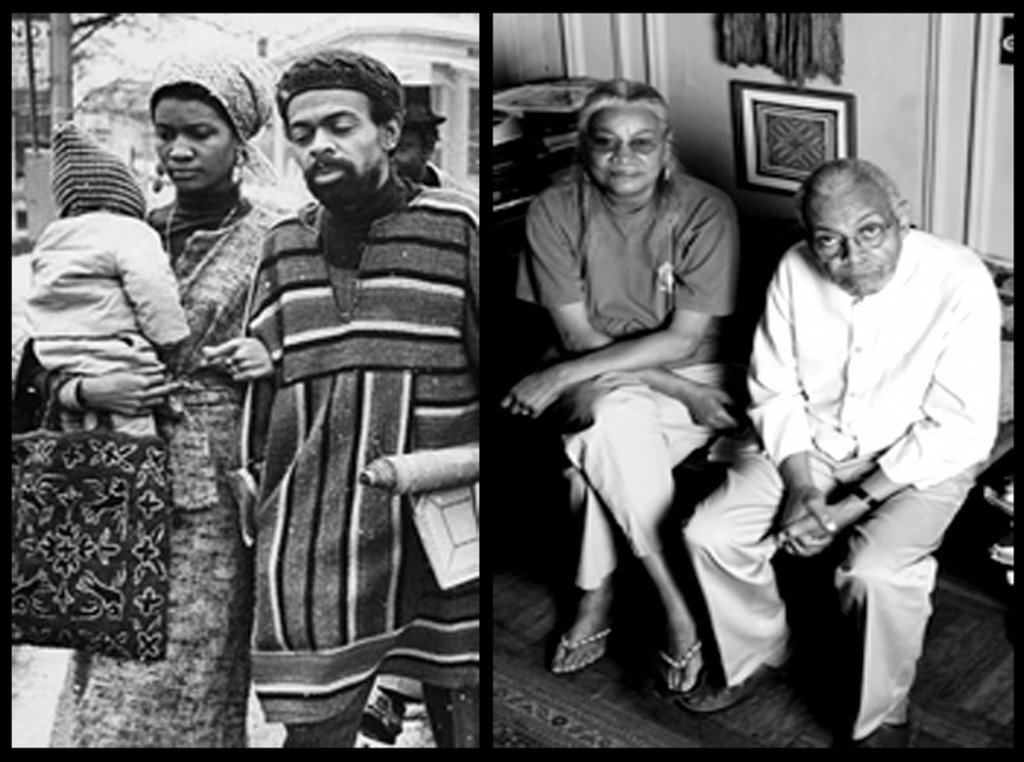

Mr. Baraka on his way to court in Newark with second wife, Sylvia (Amina), left, in 1968. He had periodic brushes with the law throughout his adult life. Neal Boenzi/The New York Times

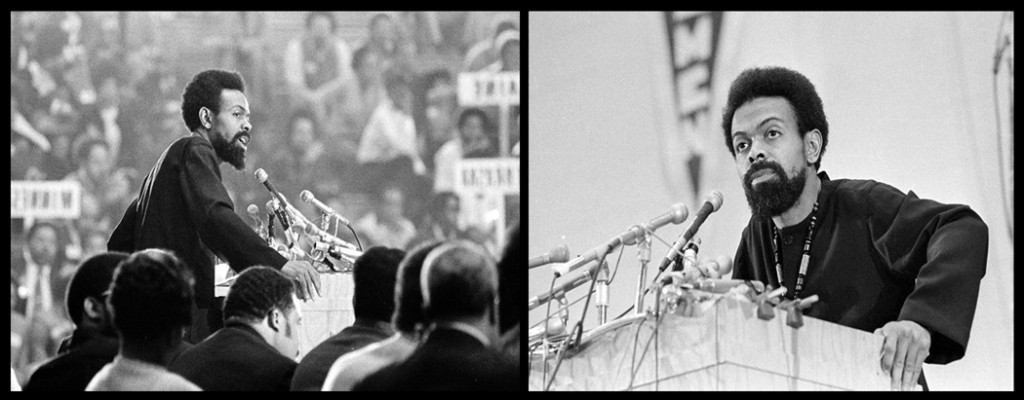

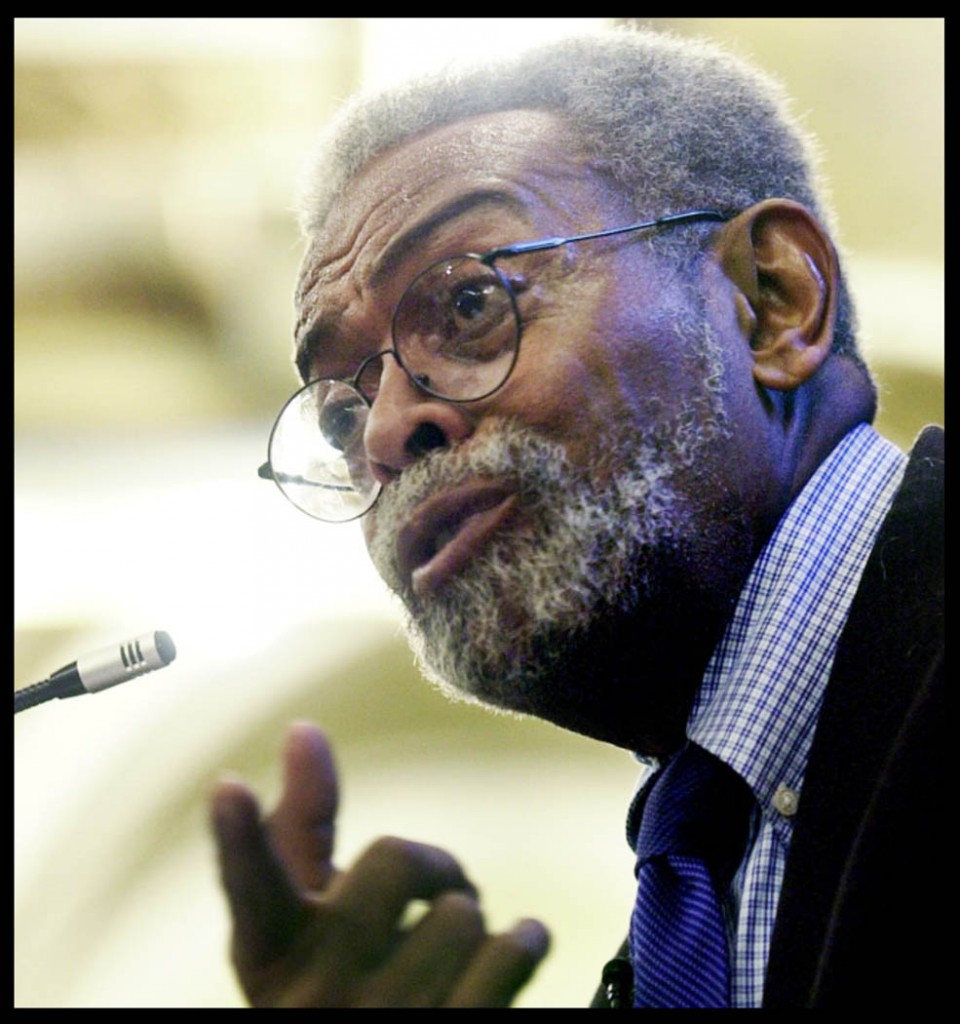

Amiri Baraka, poet and social activist speaking during the Black political Convention in Gary, Indiana on March 12, 1972.

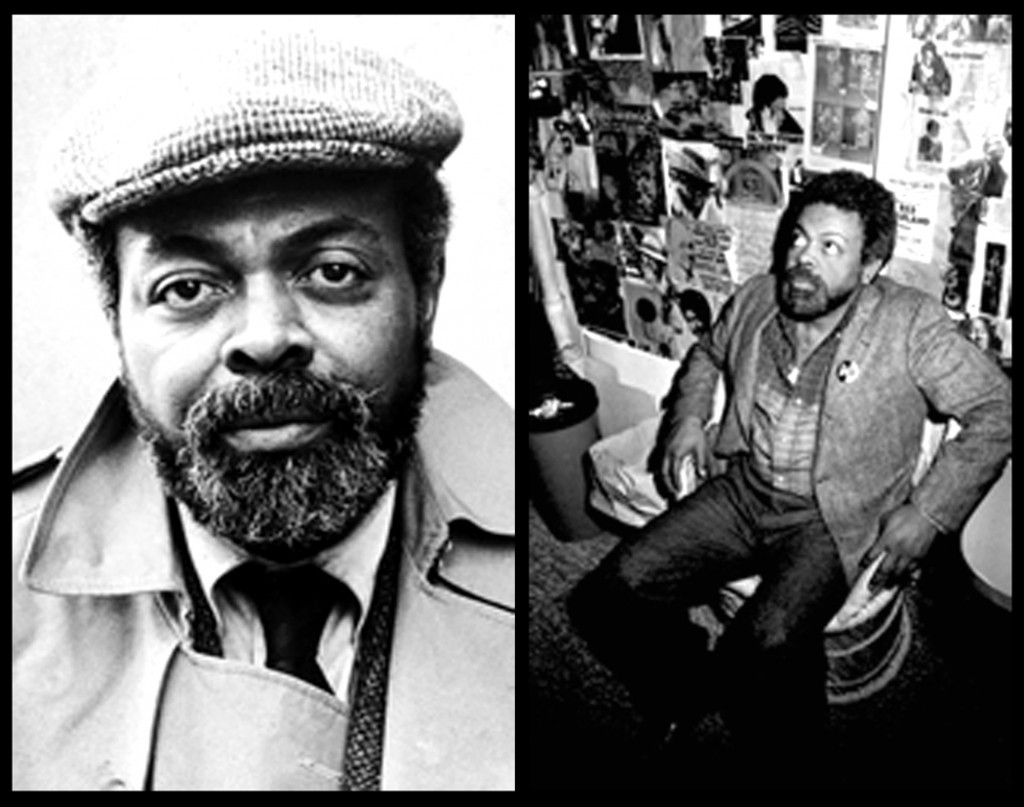

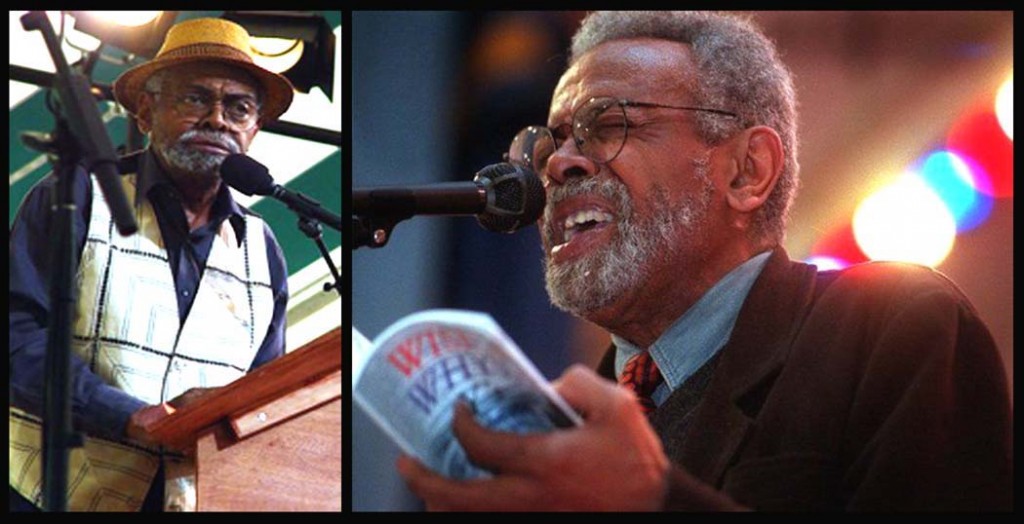

Left-Amiri Baraka (1970) Right- Amiri Baraka (photo: Brian McMilen, 1980)

Mr. Baraka with the poet Maya Angelou in 1991 in Harlem during an event at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.Chester Higgins, Jr./The New York Times

Left-Amiri Baraka reading at the Dodge Poetry Festival (2003)

Right-Amiri Baraka pictured at a Newark school in this 2000 Star-Ledger file photo. (Patti Sapone/The Star-Ledger)

Left-Amiri Baraka at the Miami Book Fair International, 2007

Right- Amiri Baraka addressing the Malcolm X Festival from the Black Dot Stage in San Antonio Park, Oakland, California while performing with Marcel Diallo and his Electric Church Band

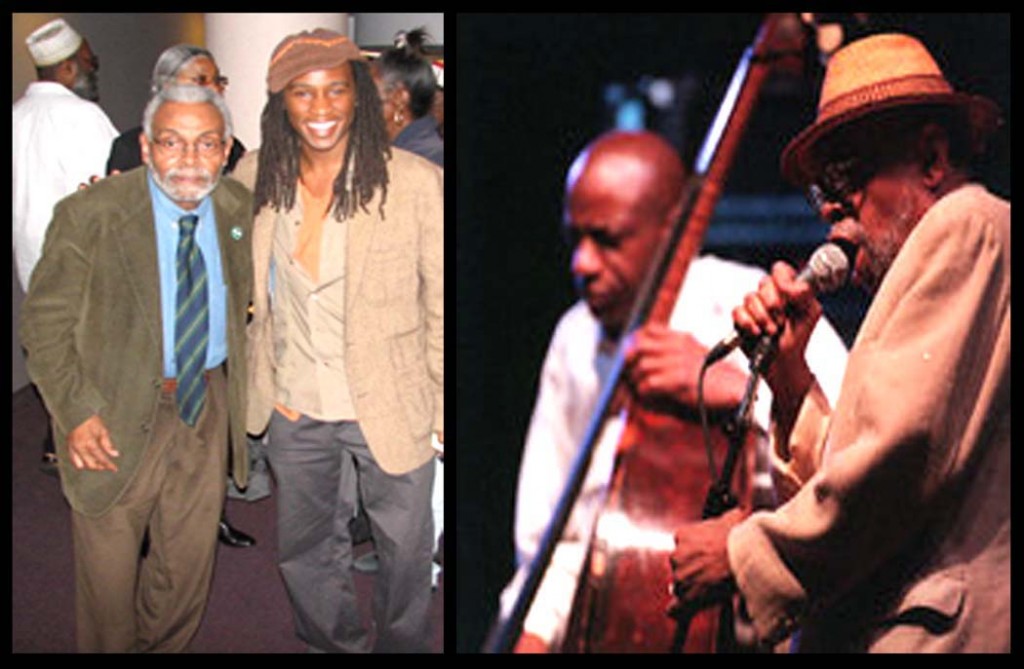

Left-Amiri Baraka and Wilber Morris in Finland(2001)

Left-Amiri Baraka and Wilber Morris in Finland(2001)

Right- Baraka defends “Somebody Blew Up America” (2003)

Left-Baraka and M.K. Asante, Jr. in Newark, NJ (2006)

Right- Mr. Baraka with Reggie Workman on bass during a performance of the New York Art Quartet at the South Street Seaport in 1999. Ozier Muhammad/The New York Times

Left- Mr. Baraka on his way to court in Newark with second wife, Sylvia (Amina), left, in 1968.

Right-Amina and Amiri Baraka at home (photo: Ryan Joseph, 2007)

The following are some of Amiri Baraka Videos on YouTube:

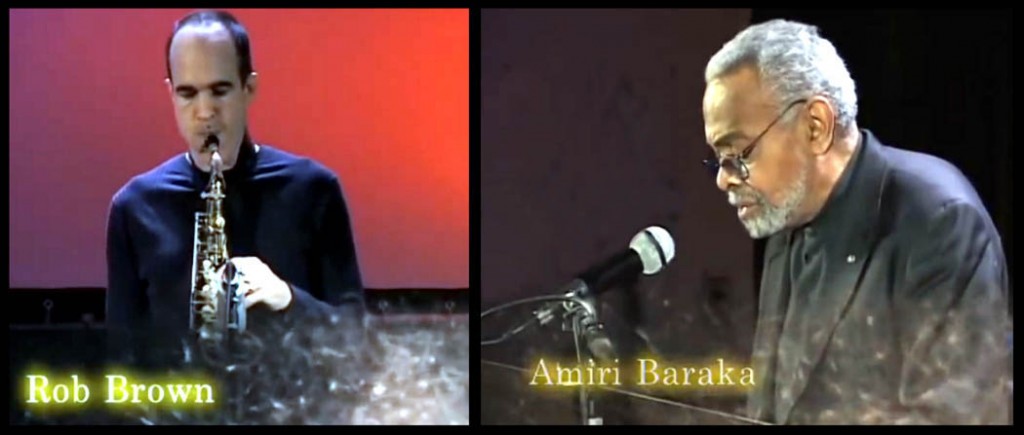

Amiri Baraka “Obama Poem” Uploaded on December 9. 2009 (2:49 minutes)

“Obama Poem” by Amiri Baraka with Rob Brown saxophone, recorded live on February 21, 2009 at The Sanctuary for Independent Media in Troy, New York.

Link to YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QPK9eH4EFTU

Amiri Baraka “Somebody Blew Up America Poem” Uploaded on December 16, 2009

(9:31 minutes)

“Somebody Blew Up America Poem” by Amiri Baraka with Rob Brown saxophone, recorded live on February 21, 2009 at The Sanctuary for Independent Media in Troy,New York.

Link to YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KUEu-pG1HWw

“9/11 CONTROVERSY

In 2002, as poet laureate of New Jersey, Baraka drew accusations of anti-Semitism over his poem “Somebody Blew Up America,” which included material borrowed from conspiracy theories in an account of the September 11, 2001, attacks.

Baraka refused then-New Jersey Governor Jim McGreevey’s request for him to resign and, in response, state lawmakers passed a law to eliminate the position of poet laureate.

“Poetry is underrated,” Baraka told the New York Times in 2012, “so when they got rid of the poet laureate thing, I wrote a letter saying, ‘This is progress. In the old days, they could lock me up. Now they just take away my title.’”

By David Jones

Please Visit the following link for more information:

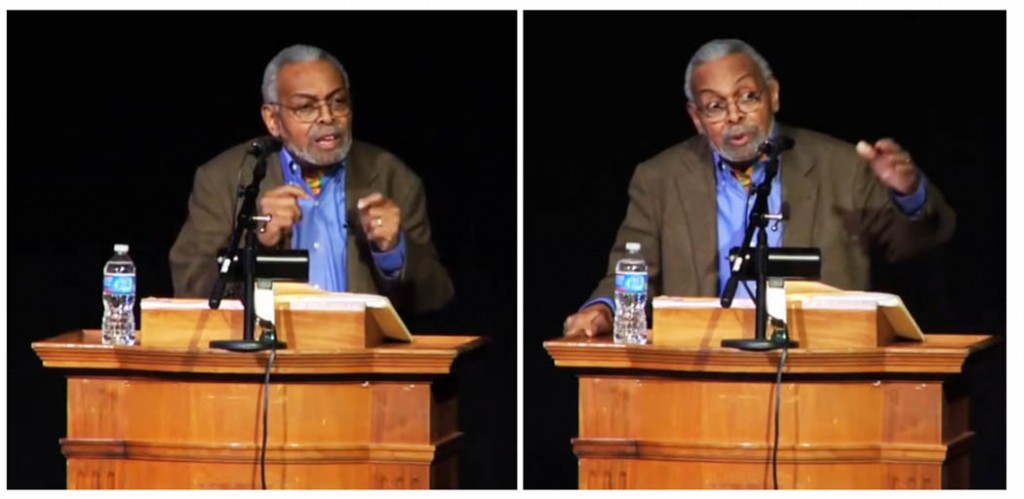

Amiri Baraka speaks to the importance of Afican-American history

University of Virginia

Amiri Baraka speaks to the importance of Afican-American history in this final event of the 2011 Community MLK Celebration. He reads from his works and takes questions from the audience gathered at Culbreth Theatre, University of Virginia

Video on YouTube, upload on February 3, 2011, (1:20.06 hours)

The link to YouTube : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nR5pdz2uGFc

Amiri Baraka — who died at age 79 — wrote prolifically and in many genres. He published plays, poetry, essays, several volumes of musical criticism, short stories and one novel, which was based on Dante’s Divine Comedy. A selection of his works include:

1958: “A Good Girl Is Hard to Find”

Baraka’s first play was performed at the Sterington House, a jazz club in Montclair.

1961: “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note”

His first collection of poems, it was published while Baraka was living in Greenwich Village, a friend of Beats Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac.

1963: “Blues People: Negro Music in White America”

His first volume of music criticism, it looked at the span of black music from the slavery era to the 1960s.

1964: “The Dutchman”

This play — about a rage-filled encounter between a black man and a white woman on a New York City subway — was performed at the Cherry Lane Theater, and won Baraka the Obie Award for best play of the year. (The Obie is the major prize for off-Broadway theatrical productions in New York).

1965: “The System of Dante’s Hell”

Baraka’s first novel, and one of his relatively few prose fiction works, was based on Dante’s Divine Comedy

1966 “Home: Social Essays”

Some early controversies surrounded the essays in this collection, which some accused of sexism and homophobia.

1967: “Black Magic”

This volume of poetry was written after Baraka left Greenwich Village for Harlem, and disassociated from the Beats. In Harlem, he helped found the Black Arts Movement, a parallel to the Black Power movement.

1968 “Home on the Range”

This play was written and performed as a benefit for the Black Panther party

1984: “Daggers and Javelins”

In this book of essays, Baraka moved away from his embrace of Black nationalism and started to embrace more Marxist theories.

1984: “The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka” Looking back over his career in this memoir, Baraka recalled feeling shut out from the world of poetry as a young man.

1995: “Wise Why’s Y’s: The Griot’s Tale” His first work of poetry in a decade, this book was one five-part epic poem about the African American experience.

2003: “Somebody Blew Up America & Other Poems”

The title poem, written in the wake of the 9/11 attacked, included lines that were interpretted as anti-Semitic.

2009: “Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Classical Music”; A collection of essays on jazz greats, it was one of his last publications.

Sources: The Poetry Foundation, The Academy of American Poets/Poets.org,

Please visit the link below for more information:

Mr. Baraka was famous as one of the major forces in the Black Arts movement of the 1960s and ’70s, which sought to duplicate in fiction, poetry, drama and other mediums the aims of the black power movement in the political arena.

Among his best-known works are the poetry collections “The Dead Lecturer” and “Transbluesency: The Selected Poetry of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones, 1961-1995”; the play “Dutchman”; and “Blues People: Negro Music in White America,” a highly regarded historical survey.

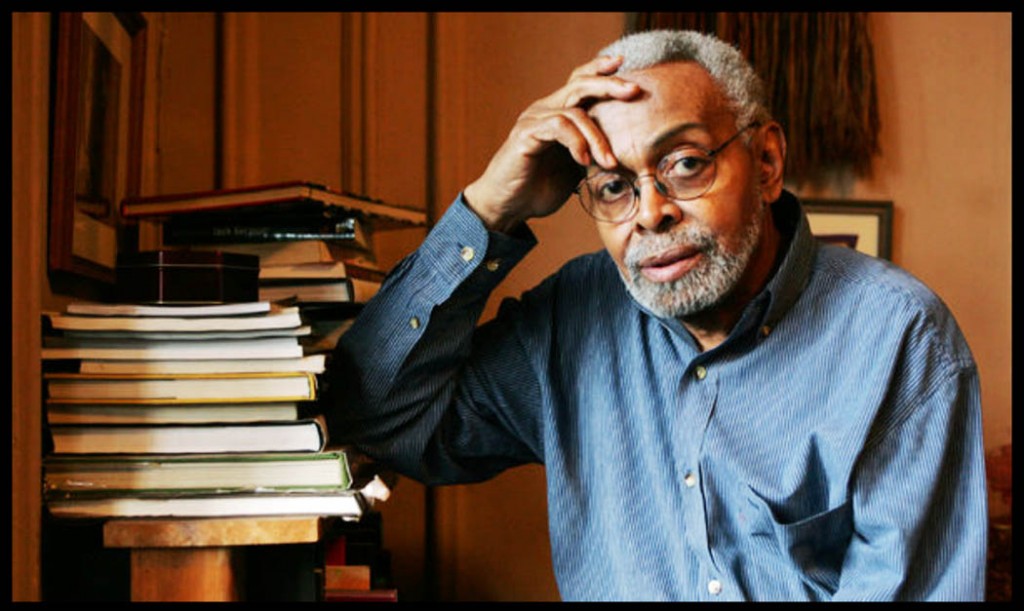

Mr. Baraka at home in Newark in 2007. He was a lecturer and poet whose words were celebrated by some, but considered hateful by others. Ruth Fremson/The New York Times

Over six decades, Mr. Baraka’s writings — his work also included essays and music criticism — were periodically accused of being anti-Semitic, misogynist, homophobic, racist, isolationist and dangerously militant.

But his champions and detractors agreed that at his finest he was a powerful voice on the printed page, a riveting orator in person and an enduring presence on the international literary scene whom — whether one loved or hated him — it was seldom possible to ignore.

“Love is an evil word,” Mr. Baraka, writing as LeRoi Jones, the name by which he was first known professionally, said in an early poem, “In Memory of Radio.” It continues:

Turn it backwards/see, see what I mean?

An evil word. & besides

who understands it?

I certainly wouldn’t like to go out on that kind of limb.

Saturday mornings we listened to Red Lantern & his undersea folk.

At 11, Let’s Pretend/& we did/& I, the poet, still do. Thank God!

Among reviewers, there was no firm consensus on Mr. Baraka’s literary merit, and the mercurial nature of his work seems to guarantee that there can never be.

His early poems were praised for their lyricism and for the immediacy of their language — throughout his career, he said, he wrote as much for the ear as for the eye.

Please visit the link below for more information:

By Carolyn Kellogg

2:41 p.m. CST, January 9, 2014

A playwright, poet, critic and activist, Baraka was one of the most prominent and controversial African American voices in the world of American letters.

At that time he also co-edited a literary newsletter, The Floating Bear, published “Blues People: The Negro Experience in White America and the Music That Developed from It” (1963) and penned the play “Dutchman,” which explosively explored issues of race and gender.

“I can see now that the dramatic form began to interest me because I wanted to go ‘beyond’ poetry. I wanted some kind of action literature,” Baraka wrote in his 1984 autobiography.

Baraka led the Black Arts Movement, an aesthetic sibling to the Black Panthers. Although the movement was fractious and short-lived, it involved significant authors such as Gwendolyn Brooks, Eldridge Cleaver, Gil-Scott Heron, Nikki Giovanni, Ishmael Reed and Quincy Troupe.

“[W]e wrote art that was, number one, identifiably Afro American according to our roots and our history and so forth. Secondly, we made art that was not contained in small venues,” Baraka said in a 2007 interview. “The third thing we wanted was art that would help with the liberation of black people, and we didn’t think just writing a poem was sufficient. That poem had to have some kind of utilitarian use; it should help in liberating us. So that’s what we did. We consciously did that.”

In Harlem, Baraka sent trucks into the community carrying people — including the artist Sun Ra — performing poetry, dance and music.

Baraka’s work during the 1960s included the plays “The Black Mass,” “The Toilet,” and “The Slave”; the poetry collections “Black Art” and “Black Magic”; and the provocative collection “Home: Social Essays.”

Asked by NPR in 2007 how he would define himself, Baraka said, “Well, I guess as a poet and a political activist most consistently. I’ve written in all genres. … But, you know, I guess throughout all of that, the poetry is at the base of it.”

Although he was frequently embroiled in political controversy, Baraka’s artistic achievements did not go unacknowledged. His awards include fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, a PEN/Faulkner Award, a Rockefeller Foundation Award for Drama, and the Langston Hughes Award from City College of New York.

Please visit the link below for more information:

https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/chi-amiri-baraka-dies-20140109,0,7455048.story

Some critics denounced him as buffoonish, homophobic, anti-Semitic and demagogic. For others he was a genius, a prophet, the Malcolm X of literature.

Eldridge Cleaver hailed him as the bard of the “funky facts.” Ishmael Reed credited the Black Arts Movement for encouraging artists of all backgrounds and enabling the rise of multiculturalism. Scholar Arnold Rampersad placed him alongside Frederick Douglass and Richard Wright in the pantheon of black cultural influences.

“From Amiri Baraka, I learned that all art is political,” Pulitzer Prize-winning dramatist August Wilson once said, “although I don’t write political plays.”

Jones left his white wife (Hettie Cohen), cut off his white friends and moved from Greenwich Village to Harlem. He renamed himself Imamu Ameer Baraka, “spiritual leader blessed prince,” and dismissed the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as a “brainwashed Negro.”

He helped organize the 1972 National Black Political Convention and founded the Congress of African People. He also founded community groups in Harlem and Newark, the hometown to which he eventually returned.

The Black Arts Movement was essentially over by the mid-1970s, and Baraka distanced himself from some of his harsher comments – about King, about gays and about whites. He kept making news.

In the early 1990s, as Spike Lee was filming a biography of Malcolm X, Baraka ridiculed the director as “a petit bourgeois Negro” unworthy of his subject.

Read more: https://www.dailystar.com.lb/Culture/Books/2014/Jan-10/243755-activist-poet-playwright-amiri-baraka-dies-at-79.ashx#ixzz2qAzTqVFj

(The Daily Star :: Lebanon News :: https://www.dailystar.com.lb)

By David Jones

NEWARK, New Jersey (Reuters) – Amiri Baraka, a controversial playwright, poet and activist who set a new path for fellow African-American artists by bringing militancy and verve to works about race in America, died on Thursday at age 79 at a hospital in his native New Jersey, a representative said.

Among Baraka’s other well-known works are his nonfiction book “Blues People: Negro Music in White America” and the poems “In Memory of Radio” and “An Agony. As Now.”

Among his accolades were the Rockefeller Foundation Award for Drama and a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Baraka over the decades loomed large as a political figure in his home of Newark, where he returned to live in the 1960s after time spent in New York.

“I always thought Amiri Baraka’s decision to come back to Newark and stay in Newark and engage Newark helped this beleaguered city recover some very important parts of its identity – its self identity – in some periods when the city was spiraling downward,” said Clement Price, a professor of history at Rutgers University.

Newark Mayor Luis Quintana said in a statement that his city mourned the death of Baraka, who he said “used the power of the pen to advance the cause of civil rights.”

“Amiri Baraka’s poetry and prose transcended ethnic and racial barriers, inspiring and energizing audiences of many generations,” Quintana said.

U.S. Senator Cory Booker, a Democrat from New Jersey, said in a statement, “My thoughts and prayers are with his children and the whole Baraka family after their

loss.”

Baraka is survived by his wife, Amina, and several children. His son, Ras Baraka, is on the Municipal Council of Newark and is a candidate to be mayor.

(Additional reporting by Eric Kelsey inLos Angeles, Writing by Alex Dobuzinskis; Editing by Cynthia Johnston, Gunna Dickson, Cynthia Osterman and Lisa Shumaker)

https://www.today.com/books/amiri-baraka-activist-poet-playwright-dies-79-2D11893442

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-25679718

Last of the Beats: Poet-playwright Amiri Baraka dies at 79

This Oct. 2, 2002 file photo shows Amiri Baraka, New Jersey’s poet laureate during a ceremony at the Newark Public Library in Newark, N.J. Baraka, a Beat poet, black nationalist and Marxist revolutionary known for his blues-based, fist-shaking manifestos, died, Thursday, Jan. 9, 2014, at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center in Newark, N.J. at age 79. AP

Read more at: https://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/amiri-baraka-dead-at-79-beat-poet-author-activist/1/335478.html

The New World

The New World

By Amiri Baraka 1934–2014 Amiri Baraka

The sun is folding, cars stall and rise

beyond the window. The workmen leave

the street to the bums and painters’ wives

pushing their babies home. Those who realize

how fitful and indecent consciousness is

stare solemnly out on the emptying street.

The mourners and soft singers. The liars,

and seekers after ridiculous righteousness. All

my doubles, and friends, whose mistakes cannot

be duplicated by machines, and this is all of our

arrogance. Being broke or broken, dribbling

at the eyes. Wasted lyricists, and men

who have seen their dreams come true, only seconds

after they knew those dreams to be horrible conceits

and plastic fantasies of gesture and extension,

shoulders, hair and tongues distributing misinformation

about the nature of understanding. No one is that simple

or priggish, to be alone out of spite and grown strong

in its practice, mystics in two-pants suits. Our style,

and discipline, controlling the method of knowledge.

Beat niks, like Bohemians, go calmly out of style. And boys

are dying in Mexico, who did not get the word.

The lateness of their fabrication: mark their holes

with filthy needles. The lust of the world. This will not

be news. The simple damning lust,

float flat magic in low changing

evenings. Shiver your hands

in dance. Empty all of me for

knowing, and will the danger

of identification,

Let me sit and go blind in my dreaming

and be that dream in purpose and device.

A fantasy of defeat, a strong strong man

older, but no wiser than the defect of love.

Way Out West

Way Out West

By Amiri Baraka 1934–2014 Amiri Baraka

(For Gary Snyder)

As simple an act

as opening the eyes. Merely

coming into things by degrees.

Morning: some tear is broken

on the wooden stairs

of my lady’s eyes. Profusions

of green. The leaves. Their

constant prehensions. Like old

junkies on Sheridan Square, eyes

cold and round. There is a song

Nat Cole sings . . . This city

& the intricate disorder

of the seasons.

Unable to mention

something as abstract as time.

Even so, (bowing low in thick

smoke from cheap incense; all

kinds questions filling the mouth,

till you suffocate & fall dead

to opulent carpet.) Even so,

shadows will creep over your flesh

& hide your disorder, your lies.

There are unattractive wild ferns

outside the window

where the cats hide. They yowl

from there at nights. In heat

& bleeding on my tulips.

Steel bells, like the evil

unwashed Sphinx, towing in the twilight.

Childless old murderers, for centuries

with musty eyes.

I am distressed. Thinking

of the seasons, how they pass,

how I pass, my very youth, the

ripe sweet of my life; drained off . . .

Like giant rhesus monkeys;

picking their skulls,

with ingenious cruelty

sucking out the brains.

No use for beauty

collapsed, with moldy breath

done in. Insidious weight

of cankered dreams. Tiresias’

weathered cock.

Walking into the sea, shells

caught in the hair. Coarse

waves tearing the tongue.

Closing the eyes. As

simple an act. You float

Please visit the link below for more poems from Amiri Baraka:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poem/18191

Leave a Reply