My Last Christmas in Wales

By John Watts ©

John Watts’ Reading at the Players

16 Gramercy Park South, New York City

On Saturday, December 12, 2015

JOHN

Tick tock, tick tock, I cry a tear for all the children born in the age of the electric clock.

EDIE

John, come help me in the kitchen, and put some more coal on the fire.

JOHN

My mother’s words still remind me of what I need to do, whether it’s washing my hands, combing my hair, or putting more coal on the fire.

EDIE

Auntie Annie and Uncle Will are going to be here any minute and I don’t want them saying anything about needing a cardigan to stay warm.

JOHN

We always have relatives over for dinner on Christmas, and Christmas 1953 is a very special occasion. This year it’s Auntie Annie and Uncle Will, who are as Welsh as anyone can possibly be, and my Uncle George, weather worn, old as the hills, and my favorite person in the world.

EDIE

Tom, stop fiddling with that clock.

TOM

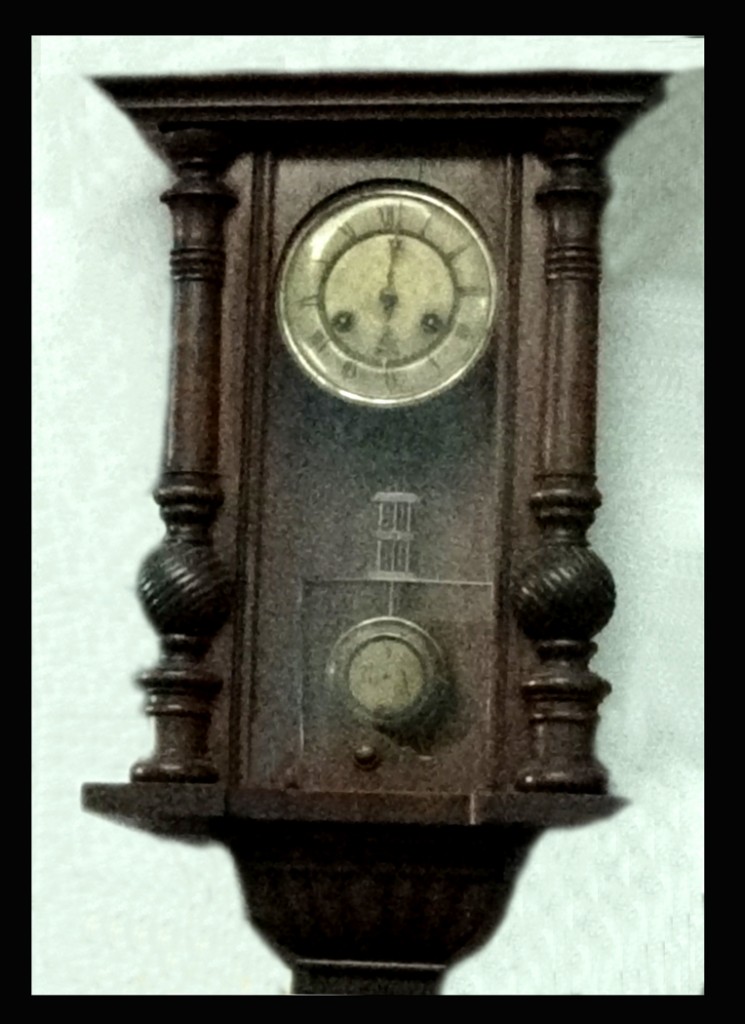

It’s three o’clock Edie, you heard Big Ben on the wireless. I’ve got to adjust the weights or we’ll be behind time for the rest of Christmas Day. There now, it’s done. We won’t lose another minute till Boxing Day.

JOHN

My childhood is filled with the winding of clocks, the chiming of Big Ben on the wireless and the little bens in all the front parlors of my relatives, a Welsh mantra, a mystical chant, the pacing of life at a verifiable rhythm. You can hurry up or slow down but there’s always the beat of the clock bringing you back to center, to home.

TOM

There it was, still on the wall. The front parlor was gone, the whole bloody house was gone, but the clock was still there. Not even the glass was broken.

JOHN

This wall mounted pendulum beauty with Big Ben chimes is not an heirloom handed down from father to son but rather the only surviving life form in a bombed house across the street from the house where I was born.

TOM

Edie, I want that clock on the ship with us. I am serious about this.

EDIE

Well you’d better make sure you do a proper job of packing it.

TOM

Right then, there’s some cardboard in my van at the station. We can start right after Boxing Day. That clock is your responsibility John. It’s not going in the trunks. We’ll build a special box and you will carry it to New York.

JOHN

Helping my father build the cardboard box cradling the precious cargo that I will carry by a roped handle onto the Queen Elizabeth is a test of manhood. Necessary preparation it seems for the journey to place where I will be living with cowboys, gangsters, and Doris Day. I have always been in love with Doris Day.

TOM

She’ll never compare to Ginger Rogers or Jeanette MacDonald.

JOHN

My father’s vision of American beauty is firmly fixed in the nineteen thirties. Everything of value it seems happened before the war. All the little Ben’s in all the houses of my relatives seem to chime the lament, before the war, tick tock, before the war, tick tock. But the war brought the Americans and nothing has ever been the same again.

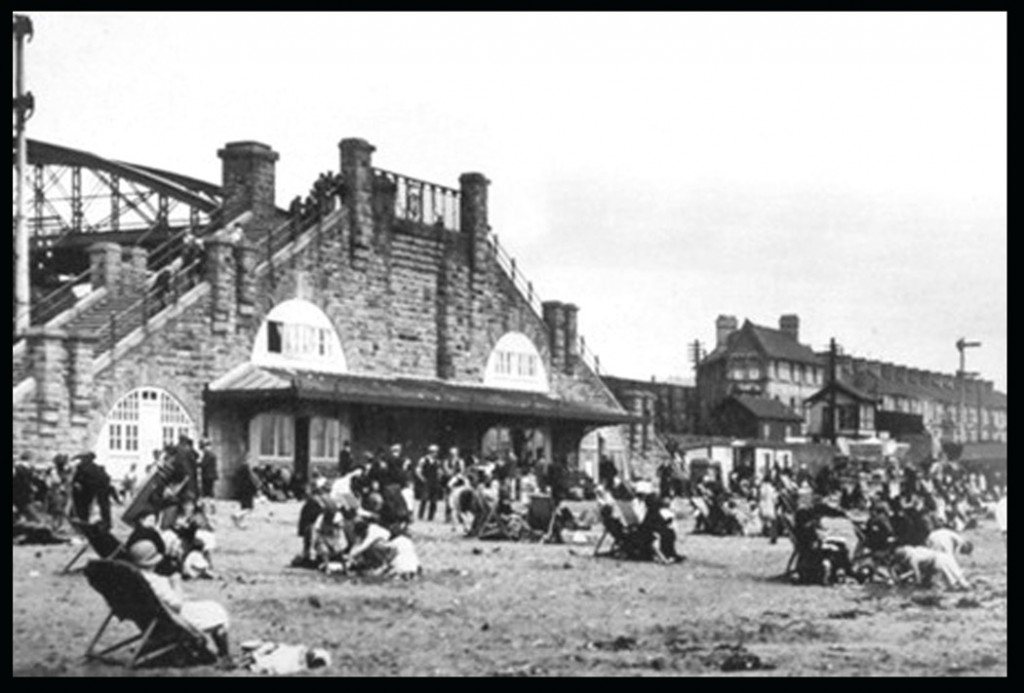

Swansea Bay, Swansea, Wales, UK

TOM

The world is changing boy, but your dreams still belong to you. So have a good look at Swansea while you still can. This will always be your home.

Swansea Bay and Victoria Park

JOHN

Sometimes when I dream, I am still almost twelve years old, an awkward Welsh boy sitting by my parlor window smelling the sea and the Christmas pudding as I listen to American Armed Forces Radio on the short-wave and dream of America. Jack Benny, Father Knows Best, Burns and Alan, for brief moments I am already there as I watch the ships on the River Tawe, some heading in to the north dock of Swansea, while others head out to sea, maybe to New York.

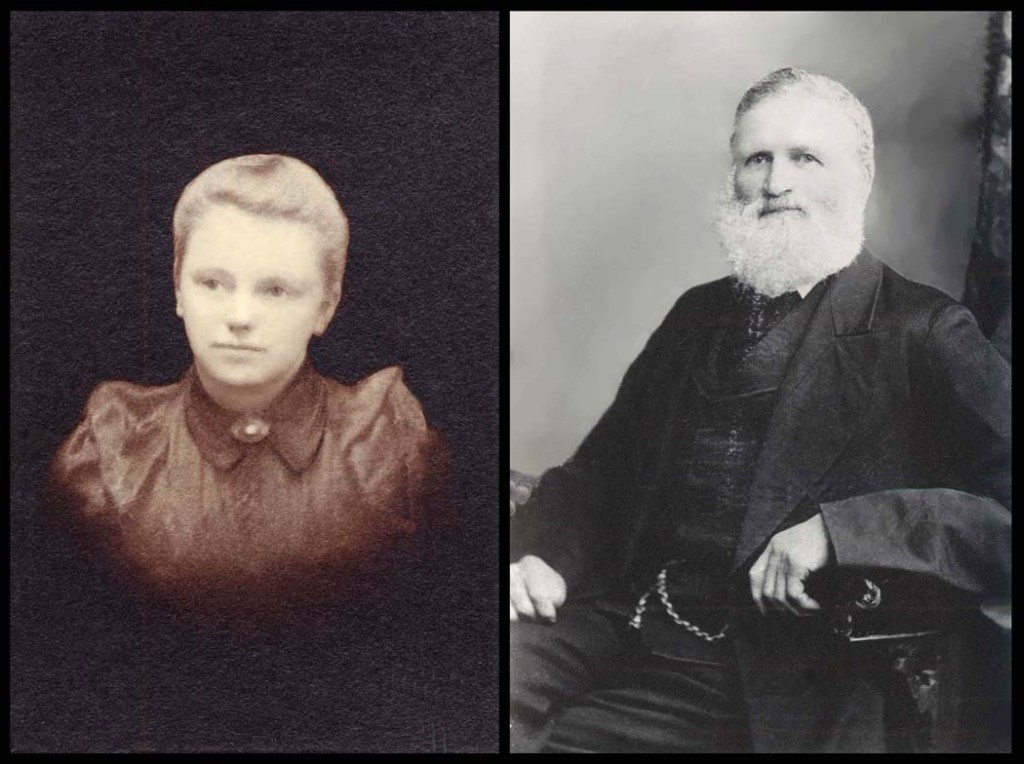

John’s Great, Great Grandma and Great, Great Grandpa, Swansea, Wales, UK

EDIE

Merry Christmas George, early as usual I see.

UNCLE GEORGE

It’s your cooking. I could smell the mince pies from my house. Well John, where are the new annuals? We better have a read before Will gets here or he’ll or he’ll hide them away and give you a copy of New Testament.

EDIE

You just let boy read for himself

UNCLE GEORGE

It’s Christmas Edie, time to have some fun.

EDIE

You are seventy-six, not twelve years old.

UNCLE GEORGE

That depends on who I’m talking too. Could I please have just one of those mince pies before dinner?

EDIE

Only one! And only one story.

UNCLE GEORGE

Well then, I’ll have the mince pie now and save the story for later, after Will finishes pouring fire and brimstone in the boy’s ear.

EDIE

Now don’t start teasing Will when he gets here. And I want you on your best behavior or our guests will think the Welsh are all ignoramuses.

UNCLE GEORGE

I’m not special enough anymore? Don’t tell me you invited an Englishman.

Left: Aunt Liz and Uncle Will

Right: John’s nephew, John DiMicelli, John Watts, middle and his cousin, Doreen Brain

TOM

She invited cousin Freddy and his new wife Francis that he met in the service and that was just the start. Unnatural that’s what it is, a Welshman marrying a German. You’ve gone too far this time Edie, inviting Francis sister and her husband, and their son. Your brother Will was right. Once a German, always a German.

EDIE

You just worry about putting this place in order for the day, Mr. Tidy Tom. Family, food on the table, and coal on the fire, that’s how I want to remember Swansea when I look back from America. I want to make this the best Christmas ever.

TOM

Are you sure you don’t want to invite the Pope?

UNCLE GEORGE

Careful what you say Tom. You’ll be living with Italian Catholics soon enough.

EDIE

Well at least George understands that the world is bigger than Swansea. And thank you George for the contribution from your ration card. You will be pleased to know that through some elaborate negotiation I have managed to acquire two chickens for Christmas dinner.

UNCLE GEORGE

You’ve out done yourself Edie. There’s even real butter, custard slices, mince pies, Welsh cakes, and unless my eyes deceive me Gaymer’s Olde English Cider. I think I died and went to heaven.

EDIE

You just make sure you don’t take more than your share, and that cider is for after dinner.

TOM

Well we can still have our annual Christmas Guinness George, with nutmeg and sugar before the, “Foreigners”, arrive.

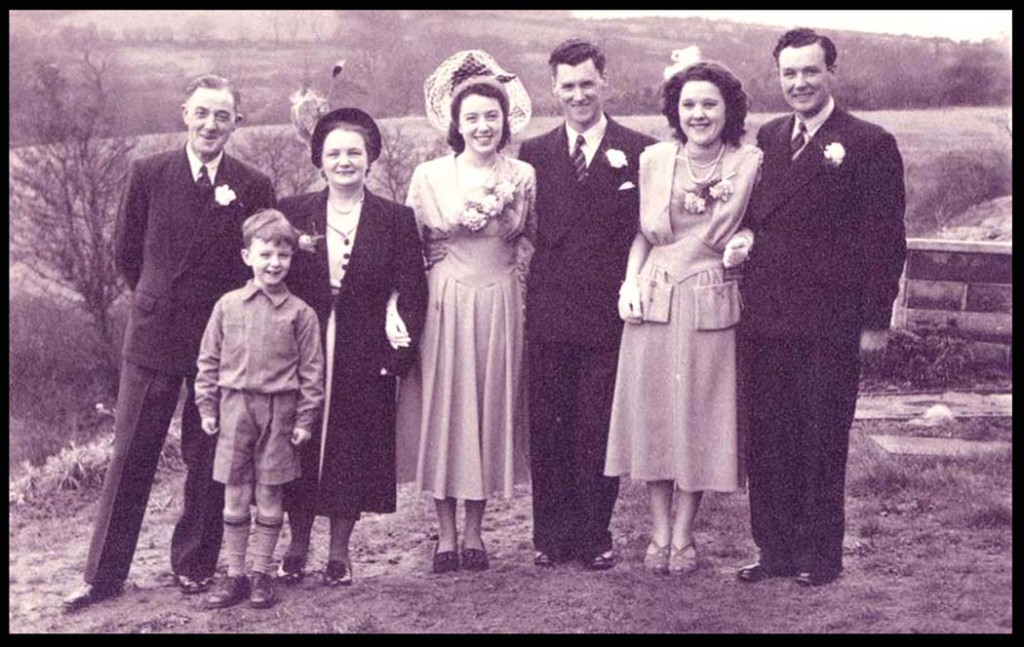

Wedding picture for John’s sister Phyllis and brother-in-law Robbie

John’s Parents, sister Phyllis, brother-in-law Robbie, friends & John in front his parents

JOHN

Nutmeg and sugar are added before their tumblers are ritually stabbed by steaming red-hot pokers from the fire.

GEORGE

That’s the Christmas way to do it Tom.

JOHN

I shudder as the dark richness of liquid foam is pierced by glowing heat, for with one quick jab and my childhood seems to vanish.

UNCLE GEORGE

John you look like you saw old Marley’s ghost. Don’t go worrying boy, this is not Dickens. If someone knocks down your sandcastle you can always build another.

EDIE

Never mind sandcastles George, he’s too much of a dreamer already. And come away from that window John. If you spent more time looking at books instead of ships you would have passed your eleven-plus.

Burrows Chambers, an office building at the Swansea Docks, Wales, UK

Burrows Chambers, an office building at the Swansea Docks, Wales, UK

JOHN

My parents are caretakers for Burrows Chambers, an office building right on the Swansea docks. We live on the top floor above the offices and from five o’clock when the workers leave we clean the rooms and prepare sixteen coal fires for the next morning. My job is to empty the ashtrays and waste paper baskets, while my father offers profound advice.

Swansea Bay and Kilvey Hill, Swansea, Wales

Swansea Bay and Kilvey Hill, Swansea, Wales

TOM

Always do the job right John, but remember to polish the brass doorknobs. Shiny knobs, that’s all they ever notice anyway.

JOHN

What my father does not know is that I have discovered the girly magazines that Mr. Owens keeps under some folders in his bottom desk draw.

TOM

You’re taking a long time in that office John.

JOHN

This discovery has revealed a whole new world inhabited by women the likes of which I have never seen.

TOM

If you’ve just going to sit there behind that desk with your hands in your trouser pockets you might as well go upstairs and finish your homework right now.

JOHN

Visions of familiar feminine faces attached to scantily dressed bodies fill my head as I leave that particular office with the cleanest ashtrays and the shiniest doorknobs in the entire building.

TOM

Although I’m sure that Mr. Owens will appreciate the excellent job you’ve done, you have raised the standard. Every one in the building will expect their office to be just a spick and span as this one. Consistency John, that’s the word to remember and you’ll always survive.

JOHN

I keep that in mind as I find other reasons to linger near that desk draw after my job is finished.

TOM

What’s the matter boy, don’t you want to roller skate tonight?

JOHN

Reluctantly I return to the hallways that belong to me when my work is done for when the offices are closed these drab empty corridors are transformed into the greatest roller skating rink in the entire world.

TOM

Now don’t go skating in the entrance hall. Your mother just finished scrubbing that floor.

JOHN

But there were no such rules on Christmas Day when my new

German cousin joins me in a roller skating chase up and down the echoing halls where marble floors made metal wheels sound like rolling thunder. Finally, Uncle George comes down the stairs and sits at the bottom holding my new Eagle Christmas Annual with stories about space men.

UNCLE GEORGE

All right boys put those skates away. It’s time for Dan Dare.

JOHN

On holidays Uncle George always reads tales of adventure. His lilting old Welsh voice, rising and falling with the victories and defeats of the heroes leaving you still and silent. We sit, roller skates hushed, to hear the latest adventures of Dan Dare, pilot of the future, as he faces the villains of outer space.

UNCLE GEORGE

“Dan aimed his ray gun at the advancing Treens. You’ll never take control of my ship.”

JOHN

The smell of pipe tobacco in my uncle’s coat pocket is comforting; everything about him is comforting. If I still believed in Father Christmas, he probably would look like Uncle George.

UNCLE GEORGE

“Dan’s space ship shot into outer space in hot pursuit of the Treens in their flying saucer”.

Row houses, Swansea, Wales

JOHN

His little row house is very close to Oxford Street School where I have learned the important lessons of life, such as how to pee slightly upward and downwind to win the distance contest in the schoolyard lavatory. Every school day I rush to join him for lunch. The smell of Spam frying with bubble and squeak envelops me as the front door opens.

UNCLE GEORGE

Put out the plates, do the bread and watch Sammy doesn’t drink the milk for the tea.

JOHN

Sammy, his cat, plays as I toast the bread on the fire. Then we eat and talk about his army days in the Bier War, always referring to the wonderful photographs on the mantle piece of soldiers all lined up, stiff as a board facing the camera. Uncle George was an army cook who hated the officers and laughs each time he tells me how he’d spit in the stew pot for the officers before serving.

UNCLE GEORGE

It adds flavor.

JOHN

I listen as if I have never heard him say these words before and every day I laugh.

TOM

John go help your mother set the table.

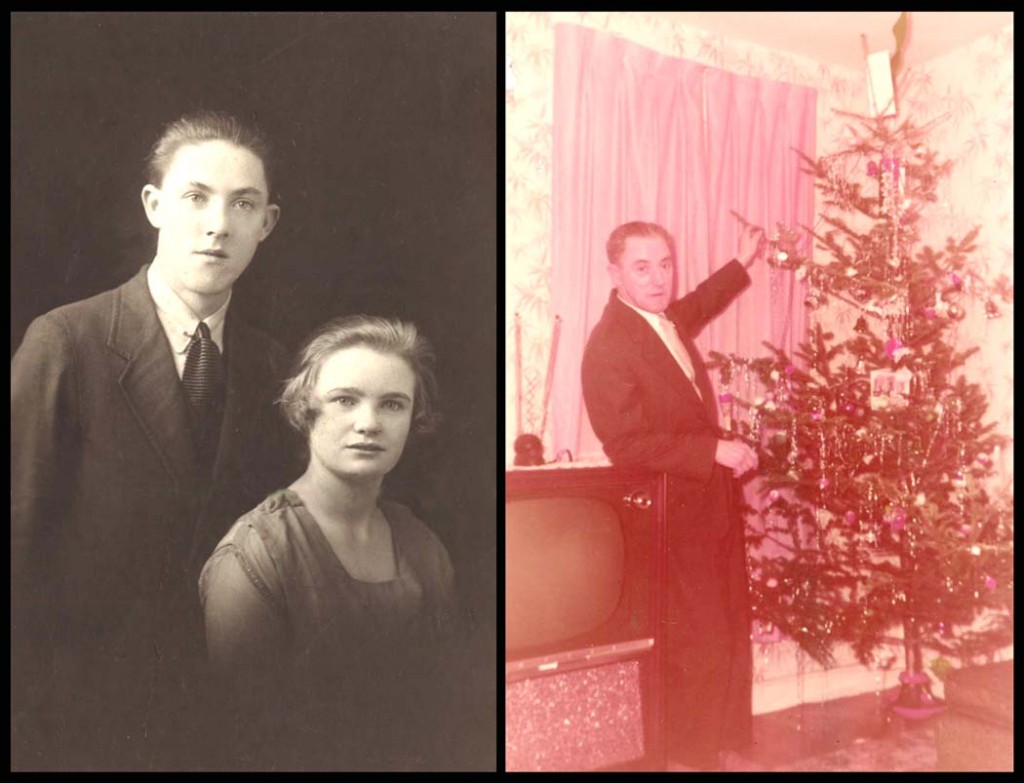

John’s Parents in 1920 and his Dad in 1954

JOHN

For Christmas dinner there is the best lace tablecloth, best dishes and the sideboard festooned with bright streamers and proudly displaying Christmas cake, trifle, mince pies and Welsh cakes.

AUNTIE ANNIE

It looks lovely Edie.

JOHN

Auntie Annie’s voice has the quality of a high pitched Welsh fog horn

AUNTIE ANNIE

You’ve made it look like a one of those color pictures in a magazine.

EDIE

All Tom noticed is that bottle of cider. He’s been eyeing it since this morning. Not a drop I told him, not a drop till after dinner.

AUNTIE ANNIE

Quite right Edie, you know what men are like once the start.

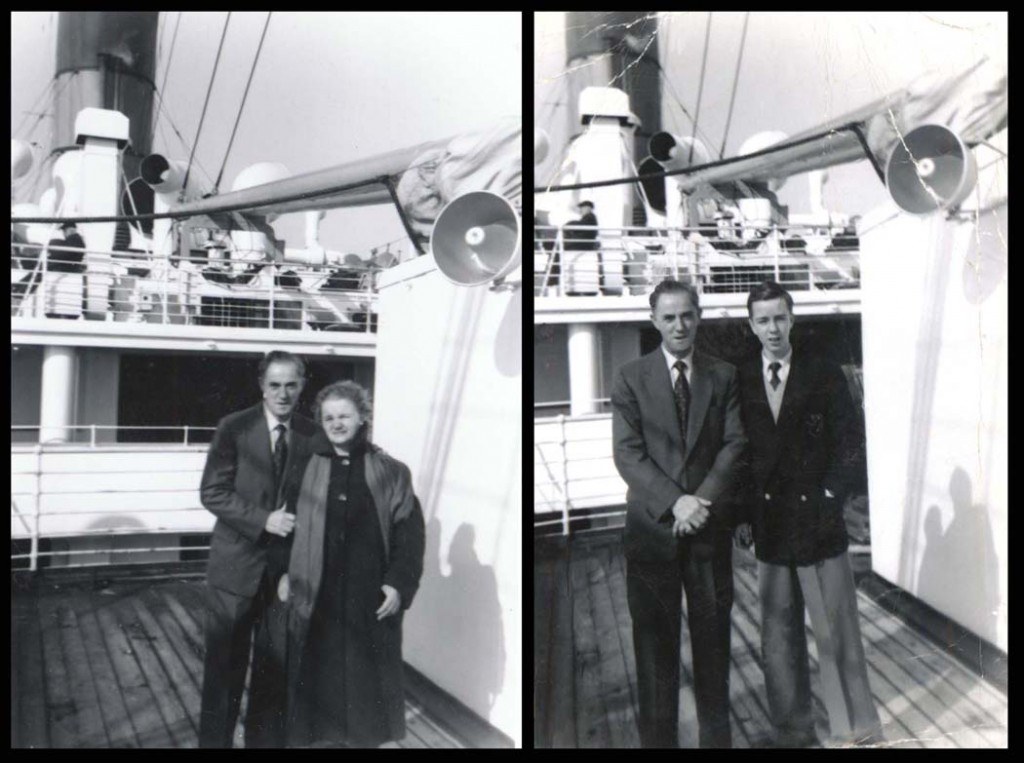

John Watts’ brother-in-law Robbie, his Dad and brother Hector

Front John Watts was 11 years old, John’s sister-in-law Audrey his Mom and sister Phyllis

UNCLE WILL

So, you’re going to be a Yank, are you? You’ll be wearing long trousers and shirts with pictures on them. Careful you don’t forget where you come.

JOHN

Uncle Will, the deacon of his Chapel in Gorsinen, speaks slowly with assure that God is on his side. He is a roly-poly man with bracers, and always a shirt and tie.

UNCLE WILL

A man is undressed without a shirt and tie.

JOHN

I do not like Sundays at Uncle Will’s house. No wireless is allowed, no newspapers, books or music, only the bible.

UNCLE WILL

The Sabbath belongs to Jesus and to Chapel.

JOHN

Chapel or not, he does not seem to mind these distractions when he comes to our house on Sundays or Christmas. Uncle Will sits quietly near the wireless in the front parlor reading the same page from the bible for half an hour while, Educating Archie, is on the BBC, a slight grin curling the edges of his mouth.

AUNTIE ANNIE

Give me the pan dripping Edie, and I’ll make a lovely gravy.

JOHN

Aunty Annie’s voice trails in from the kitchen riding the aromas of roast chicken and Brussels sprouts. You can hear her if you are down the street and all the windows are shut tight. Nothing is more embarrassing than walking along the street with some boys as the piercing trumpet of Aunty Annie’s Welshy voice lassoes you like Hopalong Cassidy chasing down a desperado.

AUNTIE ANNIE

Is that you John? Don’t you look smart in your uniform? Tell your mother I’ll be over after shopping, and not to worry about tea, I’ll be catching the bus to Kingsbridge at four.

JOHN

Even as the other boys laugh, they can all hear a relative of their own from, Merthyr Tydfil, or some other coal-mining town in the Valley.

AUNTIE ANNIE

Now Edie make sure you don’t put that bread pudding in front of Will after dinner. Just give him one helping, that’s all he needs or I’ll be widening his trousers tomorrow.

JOHN

Her voice and the aroma of roast chicken, makes my father look up from his newspaper, rolling his eyes as he glances toward the kitchen with expressions that tell far more than words.

TOM

John put one of those Paul Robeson records on the victrolla, and make it loud enough so we don’t hear Annie.

JOHN

The moment that scratchy seventy-eight bellows forth Paul Robeson’s voice, my father declares—

TOM

There’s a singer for you.

JOHN

His collection of seventy eights, mostly American, is an escape from reality we both share. Paul Robeson is his favorite and for duets nothing compares to Nelson Eddie and Janet MacDonald.

TOM

Voices of the gods!

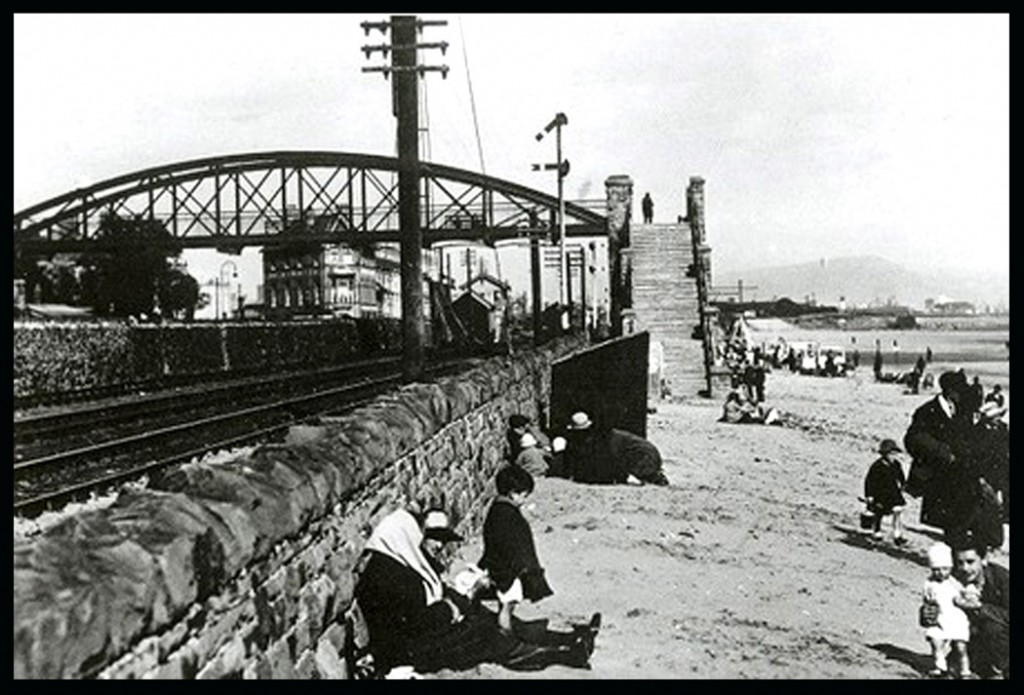

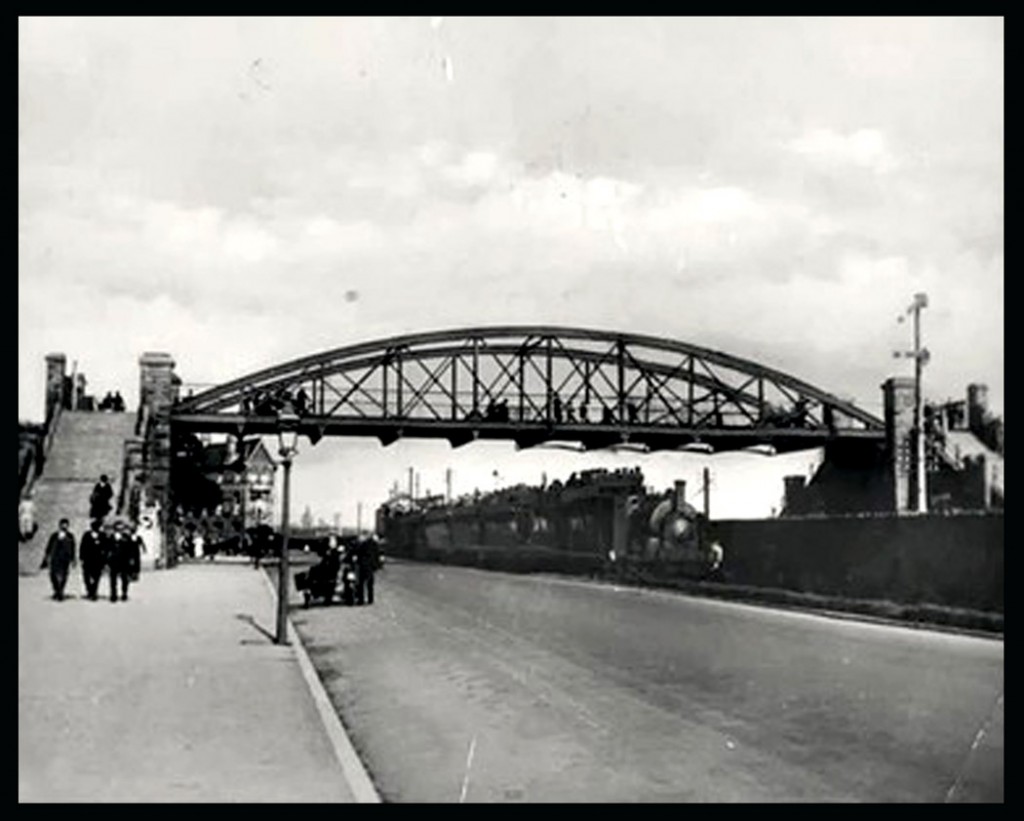

Constitution Hill, Swansea, Wales, UK

JOHN

The other thing we share is the LMS Railway Lorry, which he drives for a living. After school I rush to the Railway Station and await his arrival with parcels for the train. I help him unload, fill the van with new ones, and then off we go.

Constitution Hill, Swansea, Wales, UK

TOM

Mind those parcels and careful you don’t fall out the back.

Swansea Bay, Swansea, Wales

JOHN

Sitting in the rear of the lorry, I have a grand view of the busy streets, the row houses, the factories and always the sea. The sea makes Swansea a place of magic for it is always there, green or gray and as flat as my mother’s pancakes, while the town rises, falls, and rises again, it’s arms reaching out, cupping as much of the sea as it can into a large basin.

TOM

Hold tight John. We’re going up Constitution Hill.

JOHN

The bumpy cobblestone drive up the steepest road in Swansea lets me see the world entering through those open arms bringing dreams of America, Africa and the Royal Navy. Already a sea scout, I see myself standing on the deck of a destroyer heading out into the Bristol Channel and the Atlantic beyond.

TOM

Never forget where you come from John.

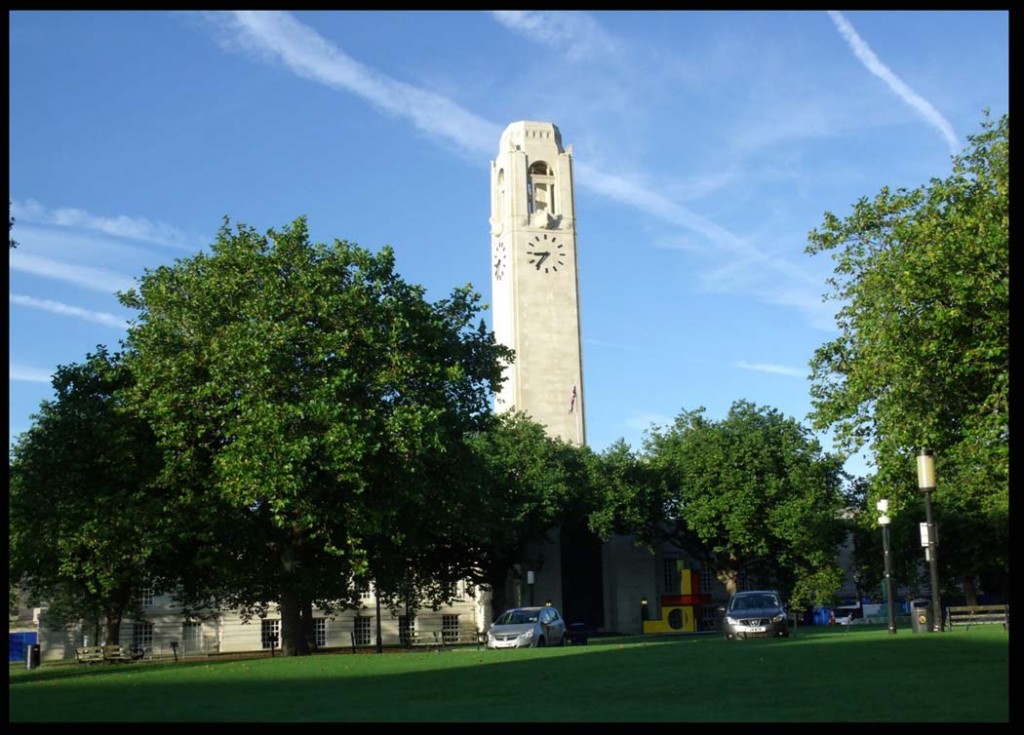

The clock tower of the Civic Center, Swansea, Wales

JOHN

A knot ties my stomach ever tighter as I glance downward at the docks, the bay, the lighthouse, and the clock tower of the Civic Center. Soon my town will disappear, replaced by cowboys and gangsters.

The Civic Center, Swansea, Wales

The clock tower of the Civic Center, Swansea, Wales

TOM

Won’t be long now boy, and we’ll be on one of those ships.

JOHN

I think of Doris Day and all the Hollywood musicals watched from the front row of the Rialto Theatre where mesmerized schoolboys sit, necks bent back as though looking at the sky while chorus lines of long legged girls dance across the screen and we all dream of America.

Swansea Bay, Slip Bridge

Swansea Bay and Victoria Park, Swansea, Wales

EDIE

We’re ready. There’s plenty of room now that we brought the tables up from the offices. We’ll put them back when we finish and no one will know the difference.

Uncle Will, Aunt Liz, Mom and Uncle Tom

UNCLE WILL

Borrowing furniture without permission is a very dangerous thing Edie. Once you start—

EDIE

I made bread pudding with big sultanas especially for you Will.

UNCLE WILL

Yes—well then—thank you for the lovely meal Edie.

JOHN

Bing Crosby is singing White Christmas on the Victrola for the hundredth time as we sit at the table to hear Uncle George propose a toast.

UNCLE GEORGE

Here’s to the American adventure yet to come.

AUNTIE ANNIE

There’s no shame in changing your mind Edie.

UNCLE WILL

Let them be Annie. It’s their decision, even if they haven’t thought through the consequences.

TOM

They’ll be meeting us at the dock with four cars. That’s enough room to put all the trunks. One of those American cars is as big as my lorry.

UNCLE WILL

There’ll be Italian Catholics driving every one of those cars.

JOHN

Uncle George quickly puts Uncle Will in his place.

UNCLE GEORGE

The Romans were in Wales before the English. You’re ancestors were probably from Sicily.

JOHN

A whisper drifts voiceless, weaving through the plates and glasses, rising up, exploding in silence, falling gently, repeating rhythmically like my father’s clock. We’ll miss you, we’ll miss you. Tick, tock, tick tock, conversation continues while out my window the early darkness of Christmas dissolves the river and lights float in an effortless parade to and from the north dock.

EDIE

Annie can help me wash the dishes while you take those tables and chairs back downstairs Tom. And George you leave some of those mince pies for other people.

JOHN

It seems like Sunday evening but there are no hand rolled left over Woodbines tonight only the best Players cigarettes.

UNCLE GEORGE

Those players make a lovely smoke Tom. A shame you don’t smoke Will. You don’t know what you’re missing.

JOHN

On Sunday nights my father ritually hands me the Cadbury’s biscuit tin in which he saves the precious remains of his Woodbines smoked down so far they turn his fingertips yellow.

TOM

Now careful with that razor blade John, cut the burned tips away but don’t waste any. I want every bit of that tobacco. There’s enough there for twenty fags.

JOHN

The remains of tobacco from old butts are made into new cigarettes in his little rolling machine, but not tonight. Tonight everything is different. No one talks about the war, no one mentions rationing, politics or the Queen. We are going to America and that is what matters.

UNCLE WILL

You’ll be home in a year. Its dog eat dog, no place for a Welshman.

UNCLE GEORGE

Jealous, that’s what you are. If they’ve got the nerve to go, then I wish them all the best. If I was younger I’d be on the boat with them. That’s where the future is.

EDIE

Who wants tea?

JOHN

Everyone responds to my mother’s call as arguments rise and fall in traditional Welsh fashion over a hot cup, that second piece of Christmas cake, and whatever can be managed within the limits of slowly tightening buttons.

UNCLE GEORGE

That was the best bread pudding I can remember.

UNCLE WILL

It’s the sultanas George, that’s what makes the difference.

JOHN

We each find our way through the night with great anticipation of what is to come. My mother’s solution, as usual, is to be as busy as she can possibly be.

EDIE

At least the offices are closed tomorrow for Boxing Day.

JOHN

My father avoids company, reads the paper and smokes.

TOM

I’m not getting up till after twelve.

JOHN

And I have my lovely window where drawn curtains keep out the night. But I am enveloped by darkness with my back to the curtain and my nose to the glass as I dream of cowboys, gangsters, and Doris Day.

UNCLE GEORGE

Take it all in boy. Remember the river; remember the lights on Kilvay Hill. Swansea will always be with you.

Kilvey Hill and Swansea City, Wales

JOHN

Uncle George, arisen from his dreams, joins me in mine. Together we stare into the darkness, his thoughts in the past, mine in the future, meeting at the center as the pendulum swings. Tick tock, tick tock, Christmas in Swansea is saying goodbye.

(Pause)

These words sustain me through my Christmas night of dreams. Then with the early light of Boxing Day, while my parents slumber, I rise to greet the silence of the sleeping Swansea streets. Quietly I pass the fishermen in their small trawlers docked near the mouth of the River Tawe.

Swansea Bay, Rainbow over Kilvey Hil, Swansea, Wales

Swansea Bay, and the Clock Tower, Swansea, Wales

FISHERMAN

Watch your feet on those nets boy or you’ll end up in the river with the fish.

JOHN

The bombed out pier ahead of me, juts out into the Bristol Channel as I climb the sand dunes to my right.

FISHERMAN

And don’t go playing around on those dunes. There could still be some live German mines from the war over there.

Mumble’s Head, Swansea, Wales

Mumble, Swansea, Wales

JOHN

Breathless I greet the bay stretching before me from the river Tawe to the lighthouse at Mumbles head. Here in the stillness of ebb tide, white foam rushes to a fleeting union with the sands of Swansea bay and life beyond childhood becomes more than a day dream for soon we will cross the ocean to America.

TOM

Maybe fifty-three is too old to start again Edie.

EDIE

We’ve been over this again and again. There’s no use worrying about it now.

TOM

It’s still safer to stay with what you already know.

JOHN

My sister Betty married a GI and left for Newark, New Jersey, when the war ended in forty-five and soon we will be there too.

John’s Dad, sister Phyllis, Mom, Aunt Liz, sister Betty and her husband Johny, Nutley, NJ, USA

John’s parents and their grand children Denise and John DiMicelli, Betty and Johny’s children

EDIE

Make your choices John, there’s only so much we can take with us.

JOHN

I decide what to shed and what to keep in our allotted space in the cargo hold of The Queen Elizabeth. I choose my Rupert Annuals, my Eagle annuals with Dan Dare, and of course my beloved Sea Scout uniform.

EDIE

We can use your scout uniform to wrap breakable things.

JOHN

My books become dividers between delicate white china cups and saucers wrapped carefully in socks, underwear, and my uniform.

EDIE

I want every one of those cups intact when we unpack. Do you hear me Tom?

TOM

Yes Edie.

EDIE

And every one of those plates and saucers too.

TOM

Yes Edie.

EDIE

Every one of those cups, do you hear me?

JOHN

Obediently my father complies, fully understanding the importance of symbols, for he has his treasured pendulum clock. The box for the journey sits beneath its ticking presence till the day of our departure when with great ritual he lowers the clock and our history into its cradle.

TOM

There now, it’s over and done. Your grand dad always said if you can’t find a proper place for something then there’s no need to keep it.

EDIE

Well Mr. Tidy Tom, there is nothing in these trunks that is not needed. We are moving to Newark, New Jersey where one’s needs go beyond the requirements of living in a place like Llandiello.

TOM

There’s nothing wrong with Llandiello. It’s the friendliest town in Wales. All my family are from Llandiello.

JOHN

A man of simple needs, my father is a slim, slightly balding member of the Welsh drinking class, a brotherhood of the pint, allowing him to find clarity.

TOM

A fag and a pint, that’s all I need.

EDIE

Well you certainly make sure you have enough money for both, even on five pounds a week.

JOHN

Cigarettes beer are the life blood of these grimy men of smokestacks and coal. And stubborn women are the backbone that kept them standing through the onslaught of gray poverty between the wars. Then came the fire bomb blitz of the second great war, which brought forth another of my father’s famous sayings.

TOM

If there is a god, he bloody well forgot about Swansea.

JOHN

But in their beloved ramshackle sea town, with a limited supply of beer and cigarettes, the brotherhood prevailed, still finding joy in the little moments. I was one of those moments, born in the rear bedroom of a bomb-cracked house, the middle draw of a chest of draws my cradle. My mother was thirty-eight at my birth, and my father was forty-two, that was old in those days. I’d heard the stories over and over in all the front parlors of my relatives while teacups clicked and clocks ticked.

EDIE

Newark, New Jersey, on the map it looks like it’s almost in New York City.

TOM

Well it’s not Hollywood.

EDIE

In New Jersey people work for a living, just like in Swansea, only they make a lot more money.

TOM

I bloody well hope so or we’re in a lot of trouble.

EDIE

We can’t be worse off than we are here. And besides, John will have a better chance at life in the States.

TOM

He loves the sea scouts. If we stayed here he could go in the Royal Navy or the Merchant Marine like his brother.

EDIE

I want more in life for him than being a sailor. He is not going in the navy if I have anything to say about it. Is that plain enough Tom?

TOM

Yes Edie.

JOHN

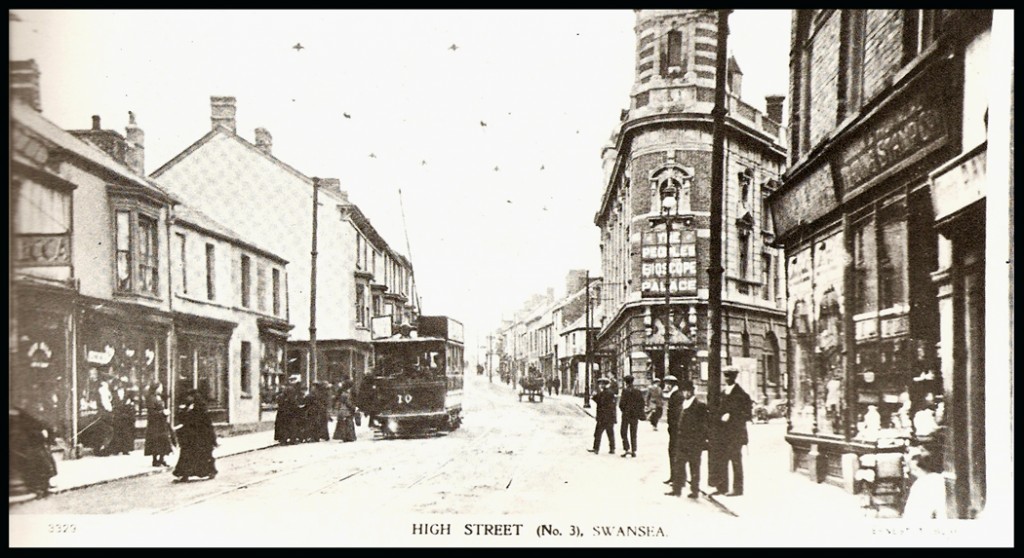

After months of preparation, we are ready. The High Street Train Station is a parade of more relatives than passengers. Uncles, Aunts and cousins, kissing and crying, break into song as the conductor calls out.

CONDUCTOR

All aboard.

JOHN

The entire station, it seems, is singing along as the train pulls away.

We’ll keep a welcome in the hillsides,

We’ll keep a welcome in the vales,

This land you knew will still be singing

When you come home again to Wales

Suddenly it becomes real. I watch the gritty factories, the smokestacks, the heaps of coal slag, and the hills covered with small row houses, slip passed the train window, slowly dissolving into the green of pastoral Wales.

All aboard.

Kilvey Hill and Swansea City, Wales

Kilvey Hill and Swansea City, Wales

Kilvey Hill and Swansea City, Wales

Kilvey Hill and Swansea City, Wales

Kilvey Hill and Swansea City, Wales

Kilvey Hill and Swansea City, Wales

TOM

Sit down Edie, you’re making me nervous.

EDIE

Annie packed some lovely corned beef sandwiches for us so we don’t have to buy food till we get to Southampton.

TOM

You can still see the countryside sitting down, that’s why they put train seats next to the window.

EDIE

And George gave John an old photo of him in his army uniform—and I think I’m going to cry again.

TOM

You haven’t stopped since we got on the train.

JOHN

A quiet chill shrouds the cabin and faces stiffen as we cross into England with all thoughts centered on the waiting ship.

TOM

We’re in a foreign country now Edie.

JOHN

Swansea’s North Dock had been my playground, but I was not prepared for the world’s greatest ocean liner, a towering city of painted white steel above a black hull, floating on the tranquil waters of Southampton dock.

TOM

You’re going to see the life in a different way from now on boy.

JOHN

His meaning is unclear as we step from the gangway to the deck. But I feel certain that it has something to do with unexpected urges below my waistline as I glance longingly at the young female passengers that seem to be everywhere I turn my head.

John’s parents in1956 John and his Dad in1956

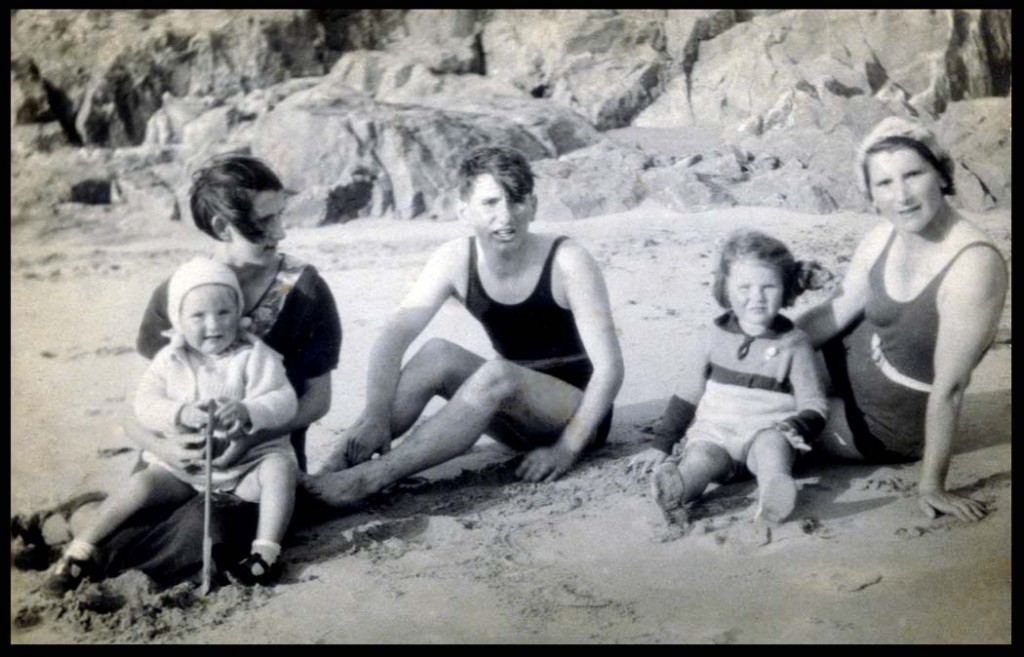

John’s cousin sits on her mother ‘s lap, Swansea, Wales

Wind Street, Swansea, Wales

Swansea Town, Swansea,Wales

Swansea Marina, Swansea, Wales

Swansea Marina, Swansea, Wales

Swansea Marina and the Bridge over River Tawe, Swansea, Wales

Sand Dunes, Swansea Bay, Swansea, Wales

JOHN

Swansea’s North Dock had been my playground, but I was not prepared for the world’s greatest ocean liner, a towering city of painted white steel above a black hull, floating on the tranquil waters of Southampton dock.

TOM

You’re going to see the life in a different way from now on boy.

JOHN

His meaning is unclear as we step from the gangway to the deck. But I feel certain that it has something to do with unexpected urges below my waistline as I glance longingly at the young female passengers that seem to be everywhere I turn my head.

TOM

Never mind the view. Just keep a firm grip on that clock.

JOHN

I try my best to focus on the roped handle of the precious cargo as we are herded through a gleaming white steel doorway into a floating city that will become our home for the next five days.

TOM

It’s like being in a London hotel.

EDIE

You’ve never been in a London hotel.

TOM

Well if I had been it would look like this. I’ll bet the cabins are just as fancy.

JOHN

In amazement, we enter the crowded wood paneled lift where my gaze quickly shifts between the breast line of young female travelers and the smooth round brass control knobs that have been well polished.

TOM

Lovely finish on those knobs John.

JOHN

We are quickly transported to the subterranean third class cabins on D deck, which is as deep into the bowels of the ship as humans could possibly be and still survive the pressure.

TOM

I think I left my stomach up on deck.

JOHN

As we descend, images from the Saturday afternoon movie serial at the Castle Theatre fill my head. The Phantom Empire, awaits us deep within the center of the earth where Gene Autry does battle to save the planet from the lost tribe of Mu, while still finding time to sing a few cowboy songs. “I’m back in the saddle again”

LIFT OPERATOR

This is D Deck ladies and gentlemen, cabins one through twenty to the left, twenty one through forty to the right.

EDIE

Is this your fancy London hotel?

TOM

Now Edie I—

EDIE

Just put the suitcases in the cabin before we go up on deck.

JOHN

Quietly I lay my head on the cabin bed plugging my nosebleed from the air pressure with soft white tissue, as I stare in wonder at the clean roll of lavatory paper in my hand. We are on our way to America where never again will I use the torn pages of The South Wales Evening Post to wipe my bum.

TOM

No time to day dream now boy, we’re leaving the dock.

JOHN

Tugs pull us away from the harbor as all the passengers come on deck and with unexpected speed our former lives fade into the wake of foaming green sea.

EDIE

Well it’s gone Tom. Fifty years of life gone.

TOM

Yes Edie.

JOHN

We retire to the lounge for morning tea, a chocolate biscuit and reflection as I think of my father’s words.

TOM

You’re going to see life in a different way from now on boy.

JOHN

This was as close to a coming of manhood conversation as we ever had until his lesson that very same day in how to sharpen a dull double-edged razor blade.

TOM

You rotate the blade with a little water against the inside of a drinking glass.

JOHN

The re-sharpened blade easily removes my three newly arrived facial hairs with a bar of soap, a shaving brush and my father’s old fashioned Gillette razor.

TOM

And don’t forget the, Imperial Leather. The sting lets you know you’ve done the job right.

JOHN

I liberally splash on my father’s after shave before we leave our subterranean den for the dinning hall where our first meal on board awaits us.

EDIE

Now this will be more like that London hotel your father remembers so well, so be on your best behavior and don’t reach for anything. The waiters will bring the food to you.

JOHN

My mother was right. Waiters in fancy dress float about our elegant table with careful humility, offering items I have never seen, as though we are royalty.

TOM

No ration cards on this ship Edie. We can eat till the cows come home.

EDIE

You just remember your manners Tom Watts. This is not one of your Wind Street pubs.

JOHN

There’s discomfort for me as I watch the waiters for I know we belong on the other side of the divide, serving rather than being served.

FRENCH GIRL

Bonjour.

JOHN

This magical word removes all my discomfort as an actual French girl with breasts, who smells like heaven, sits across the dining table facing me and speaks.

FRENCH GIRL

Bonjour.

EDIE

Start with the fork on the outside first John and then move in toward the plates. John? Are you listening to me? Never mind that girl, and put that napkin on your lap, not in your shirt. And close your mouth.

JOHN

Having worked in the houses of those with money and manners, my mother knows where to begin, and seems to enjoy being on the receiving end of all the fuss. The waiters understand and go out of their way to treat us with extra loving care.

EDIE

The waiter said we’re going to have that Italian spaghetti tomorrow night, with French bread and real butter.

JOHN

My eyes close to a vision of the French girl sucking a single strand of pasta through pursed lipstick red lips.

EDIE

Eat with your eyes open and your mouth closed. I don’t want these Europeans thinking the Welsh have no manners.

JOHN

The French girl is just one of the many dignified Europeans on board. You can tell who they are by the way they walk with proud vertical heads perched on stiff spines.

TOM

They’re stiffer than the bloody English.

JOHN

Everything about the Americans however, is slightly curved from head to toe.

TOM

There’s a swagger. It’s like they own the whole bloody world. They all think they’re John Wayne.

JOHN

This image of a cowboy who speaks with a slow drawl is an irresistible vision of American manhood. Whenever I see the French again girl I swagger passed wanting to say something in cowboy like, “Howdy Mam”. But these well-practiced words become only muttered whispers through clenched teeth, as she smiles and continues walking. Proud Europeans and swaggering Americans however, never diminish my father’s commitment to home, especially when they refer to him as, English.

TOM

English, you hear that?

JOHN

Back in the safety of our cabin my father riles against the insult.

TOM

If I called that Frogy, a bloody German, he would flatten me with one punch.

JOHN

Then he touches the cradle of his precious clock.

TOM

This is all we have left of home John, and now it’s your job to carry it safe and sound off this ship.

JOHN

For the next five days I return to the cabin several times a day, to be certain it is still there. Then I explore every corner of the lower decks where on the second day at sea a steward shows me how to walk like a sailor to counter the role of the ship.

EDIE

I’m going to be sea sick again Tom. It’s worse than the boat to Ilfracome.

TOM

Well they say the third day at sea is the worst so you’ve only got one more seasick day to get through.

EDIE

You have a wonderful way with words.

TOM

Just count down the days Edie.

EDIE

Why don’t you go up on deck and watch the ocean. Maybe you’ll see a Whale or something.

TOM

It’s not good to look at the sea when there are big swells like this. You keep seeing the horizon going up, and down, and up again.

EDIE

I’ll show you some up and down if you don’t leave this cabin right now.

JOHN

The dreaded third day arrives but the sea is calm, the sun is shining, and my mother is happy. Everyone keeps their dinner in their stomachs as I watch the French girl raise fork to mouth, and swallow gracefully, keeping her perfectly formed lips completely closed.

EDIE

This is what an ocean voyage should be, new people to talk to, lovely food, even a piano player in the lounge, and the stars at night look so clear you can touch them.

TOM

They look better than this in Llandeilo.

EDIE

Well then, why don’t you swim back to Llandeilo?

JOHN

Our last day at sea is just as calm as I watch the French girl play table tennis on deck in white shorts and a perfectly fitted, white sweater. Finally I tear myself away from this vision of heaven, to check once more on the precious cargo. But lust wins over logic as I glance back watching her reach for the little white ball rolling to starboard. Quickly I retrieve the tiny ball and hand it to her as she smiles and our eyes meet.

FRENCH GIRL

Merci Beaucoup.

JOHN

A strange sensation convinces me that the clock is safe and so I remain on deck till fog rolls in blocking my romantic fantasy, and keeping us from our destination for one more night.

BLACK MAN

This is an exciting evening young man.

JOHN

Lonely Irish songs from the foggy deck envelope me as I turn to face the voice.

BLACK MAN

Is your family emigrating?

JOHN

In the dim light I see a tall man in a suit with skin as black as coal, and so begins my first conversation with someone of another race. My father comes from the lounge to join us and after a long conversation the man returns to his cabin.

TOM

That is a gentleman. He reminds me of Paul Robeson. But mind you don’t talk to those tinkers.

JOHN

This disparity makes the black man and the Irish singers more intriguing as we return to the lounge joining the other third class passengers dressed in their Sunday best.

TOM

Bloody fog, might as well be in Swansea.

EDIE

That’s all right Tom, we’ll land on your birthday.

TOM

I put on a suit and tie, and for what?

EDIE

The fourth of May nineteen fifty-four will be a very special occasion. Now drink your Guinness and let’s enjoy our last night on board.

TOM

Edie, we’ve made a hell of a mistake.

EDIE

Well it’s too late to turn back now. I hope they don’t have to wait for us all night on the docks.

TOM

Those American cars are big enough to sleep in. They’ll be fine as long as none of those gangsters are around.

EDIE

Don’t be daft Tom. It’s not the films.

TOM

Well then, maybe they’ll drive home to Newark, and be back in the morning.

JOHN

Drive home my father says. Americans don’t travel by bus they drive home and this they do in shiny cars with chrome bumpers and radios. Visions of a pink Cadillac convertible corrupt my innocence as I dream of sitting in the back seat with the movie star of my dreams. But I am conflicted. My heart wants Doris, while my lower parts yearn for Marilyn.

EDIE

The boy’s day dreaming again Tom, you’ve probably got him worrying about those gangsters.

TOM

With that smile on his face, its girls he’s thinking about.

JOHN

Three times in a row I had watched, Diamonds Are A Girls Best Friend, at the free movie theatre on board. Marilyn’s bare shoulders, the pink satin dress, and that voice, that sultry voice, were seared in my brain forever. So, lost at sea, at the age of eleven and three quarters, there on my subterranean bunk bed till morning comes, I blissfully commune with Marilyn.

TOM

Wake up boy. We’re at the docks.

JOHN

I am down from the bunk and into my clothes.

TOM

Brush your hair before you go on deck.

JOHN

I climb the stairs till I’m above the water line where a small round window in the men’s lavatory frames my Hollywood dreams of America. James Cagney gangsters and their Marilyn Monroe girlfriends in tight sweaters with pointy breasts tease my imagination, confirming my father’s own words.

TOM

Your dreams belong to you boy.

JOHN

So in the early morning sunlight I observe the erect, glistening Technicolor affirmation of my pubescent journey to manhood. The Chrysler Building is my first view of New York City through a round window, as I face the urinal, head turned skyward, peeing with a smile. The future is in my hands as I cross the barrier between innocence and self-awareness discovering a new body and new culture all at once as I arrive on deck.

EDIE

Can you see them on the dock Tom?

TOM

Spivs and Yanks with flashy shirts, that’s all I see down there, and nobody has on a proper suit and tie.

EDIE

Never mind that, you just worry about what Tom Watts looks like.

JOHN

As passengers gather at the railing with tears and smiles I glide through smells from dry land, heat from the sun, and hurried voices all fighting for recognition.

EDIE

Never mind those bags John, and pull your socks up. And Tom, straighten your tie and do up your coat buttons.

TOM

Not till we leave the ship. It’s too bloody hot.

EDIE

Well at least try to look pleasant, they can see us from the dock.

PORTER

Watch your step on the gangway kid.

JOHN

The porter’s words, the ship’s horn, and the laughter, all blend into a single New York greeting.

TOM

Keep your head up boy. They’re all watching us.

JOHN

I stand at the gangway with wobbly legs and shoulders back preparing for the final descent, my left hand firmly grasping the roped handle of the time machine.

FRENCH GIRL

Au Revoir, Johnny.

JOHN

Her soft voice fades down the gangway as the French girl passes me with never a look back, her body swaying gently. She knows my name. She called me “Johnny”. I stand frozen as my father leans forward, his hand on my shoulder.

TOM

Time to leave childhood behind.

JOHN

We are dressed in our Sunday best, my mother in her brand new frock and my father in his double-breasted suit and wearing his new trilby, the rim tilted slightly like Humphrey Bogart. I lead the way as we step onto the wharf, my solemn duty accomplished. The time machine and my new found manhood have been safely brought to ground on American soil. But the sand waves of memory still stride the tenuous margin between here and there. Swansea Bay is where I will always exist, shifting with the tide, a migrant facing the certainty of an uncomfortable truth. We are all between worlds.

End of Play

If you would like to view John’s reading please visit his video on YouTube. The link is:

If you would like to view John’s reading please visit his video on YouTube. The link is:

My Last Christmas in Wales

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BaV2z32PGbg

Published on Dec 14, 2015

This was presented at the Christmas Party at, The Players, at Gramercy Park on December 12th, 2015. It is an autobiographical monologue with multiple voices recreating the experiences of an eleven-year-old boy from Christmas Day in Wales 1953, through his voyage crossing the Atlantic on board the Queen Elizabeth in 1954.

Leave a Reply