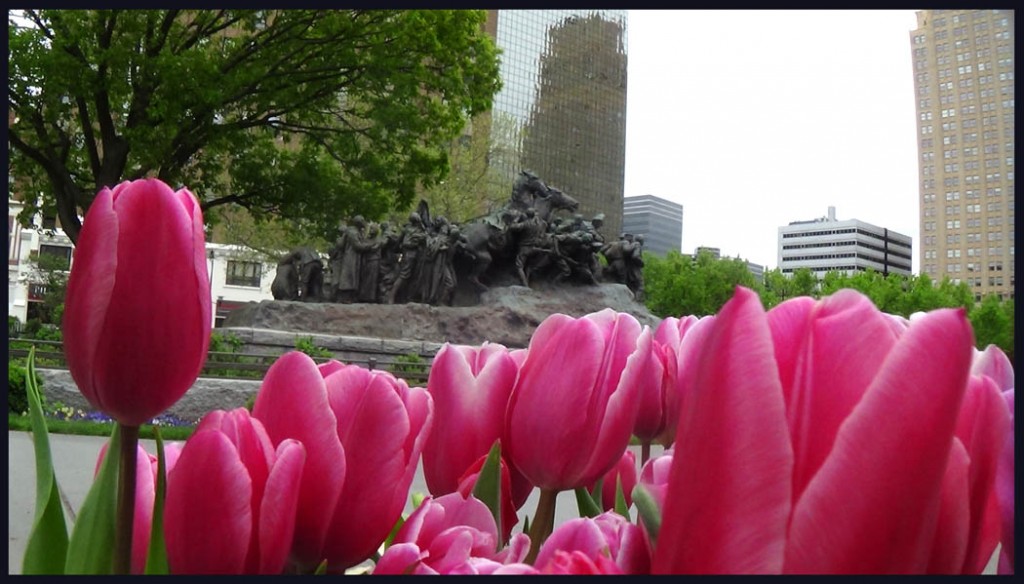

Wars Of America Sculpture at Military Park

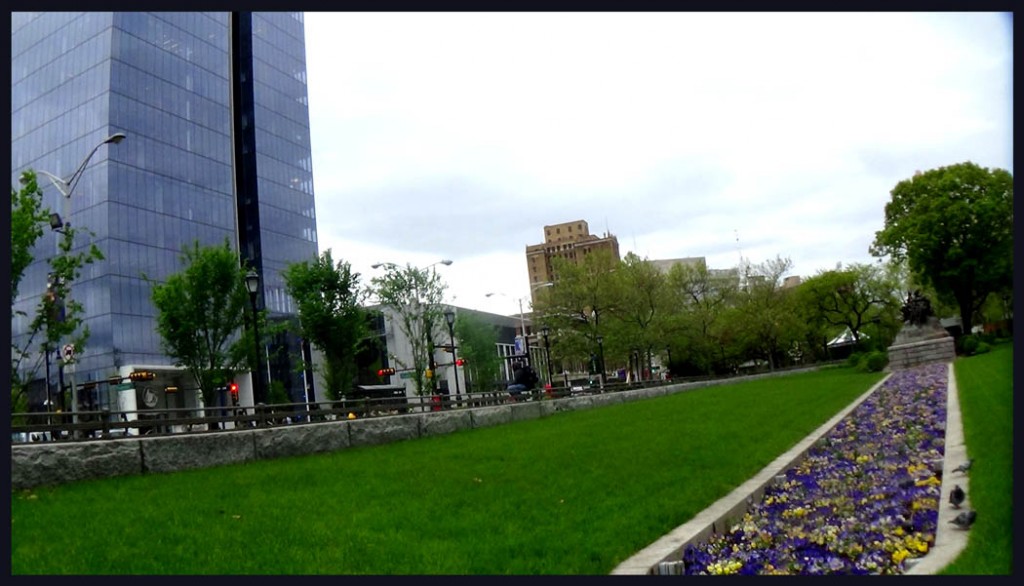

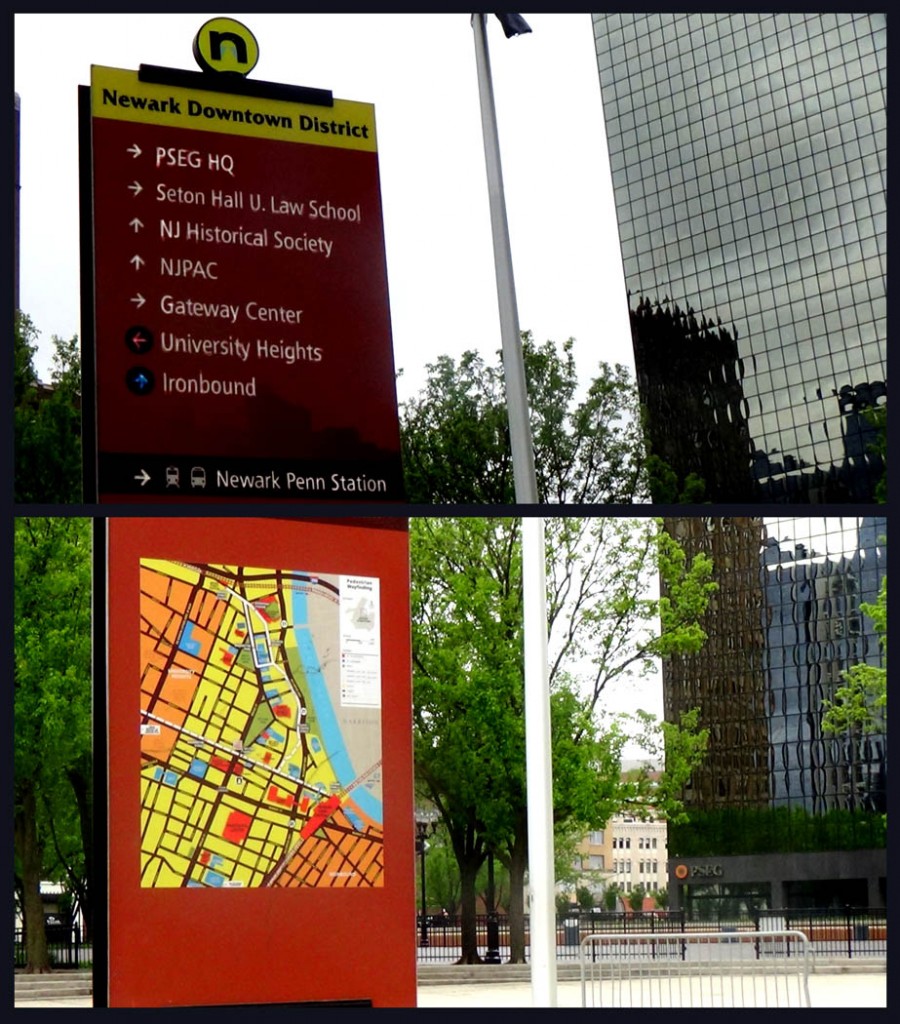

Downtown Newark, New Jersey

On Thursday, May 5, 2016

Photographs by Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts

Military Park (Newark) – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Military Park (Newark) – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_Park_(Newark)

Military Park is a 6-acre (24,000 m2) city park in Downtown Newark, Essex County, New Jersey … Military Park Commons Historic District … A statue of Monsignor George Hobart Doane, for whom the park is named, was unveiled in 1908.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wars_of_America

Wars of America

U.S. National Register of Historic Places

New Jersey Register of Historic Places

Wars of America located on Military Park,

614-706 Broad Street, Newark, New Jersey

Area less than one acre, Built 1926

Architect Borglum,Gutzon

MPS Public Sculpture in Newark MPS

NRHP Reference # 94001257[1] , Added to NRHP October 28, 1994

NJRHP # 1338[2], Designated NJRHP September 13, 1994

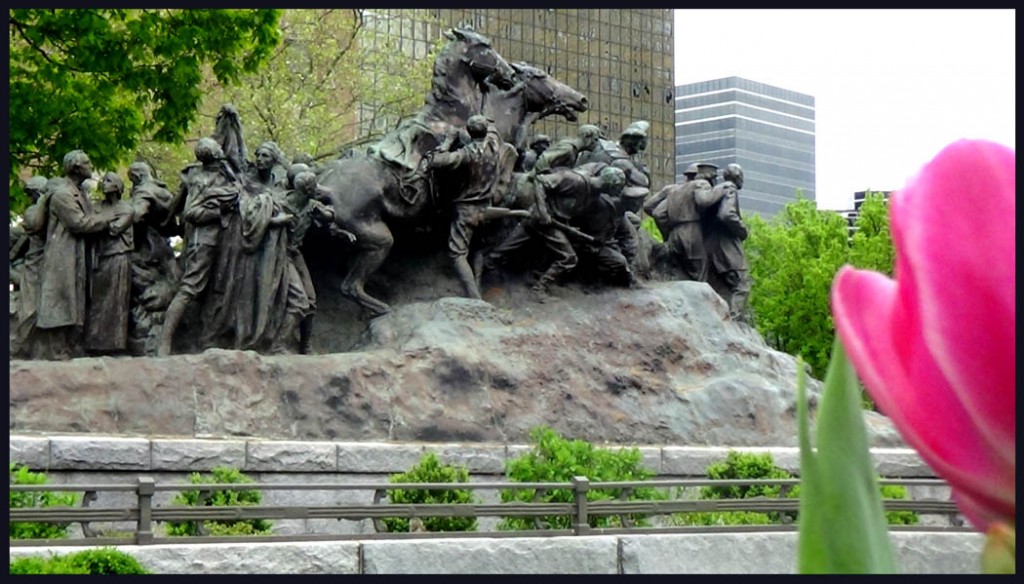

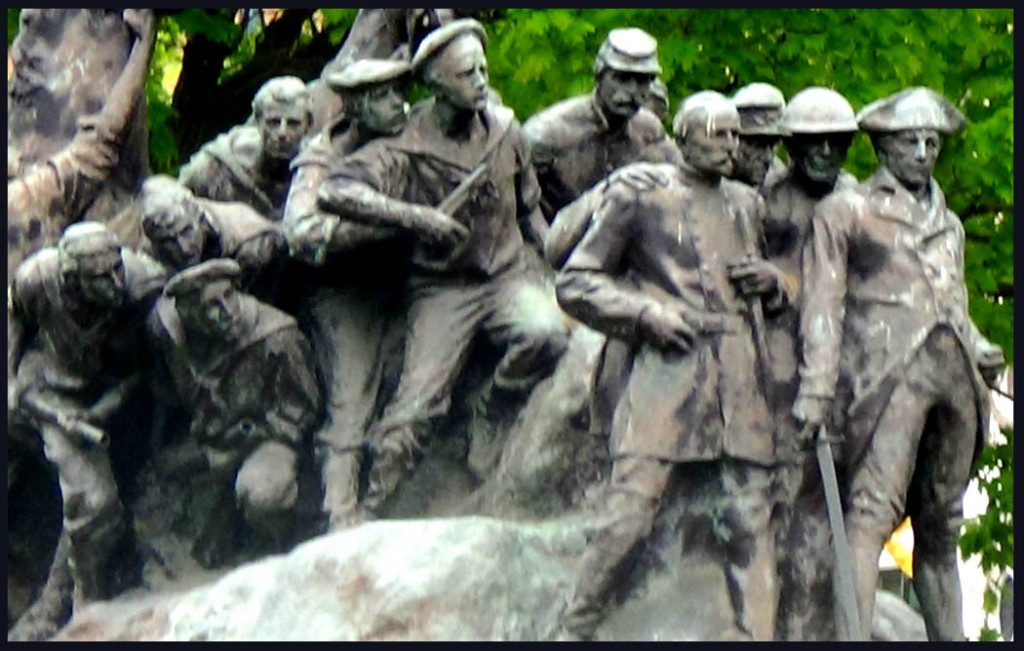

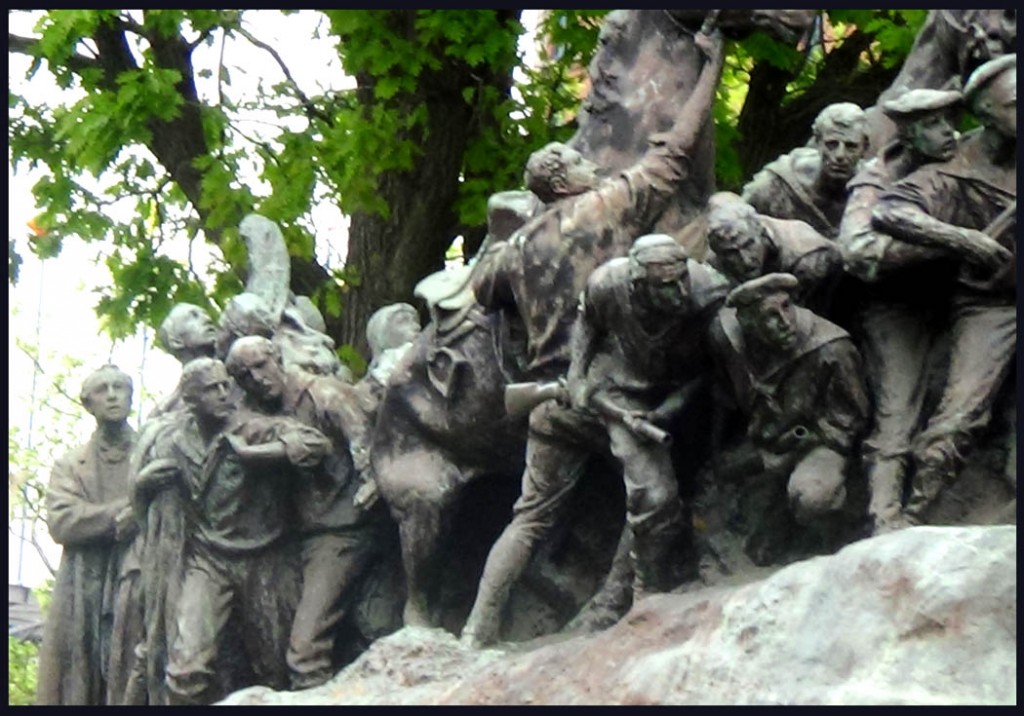

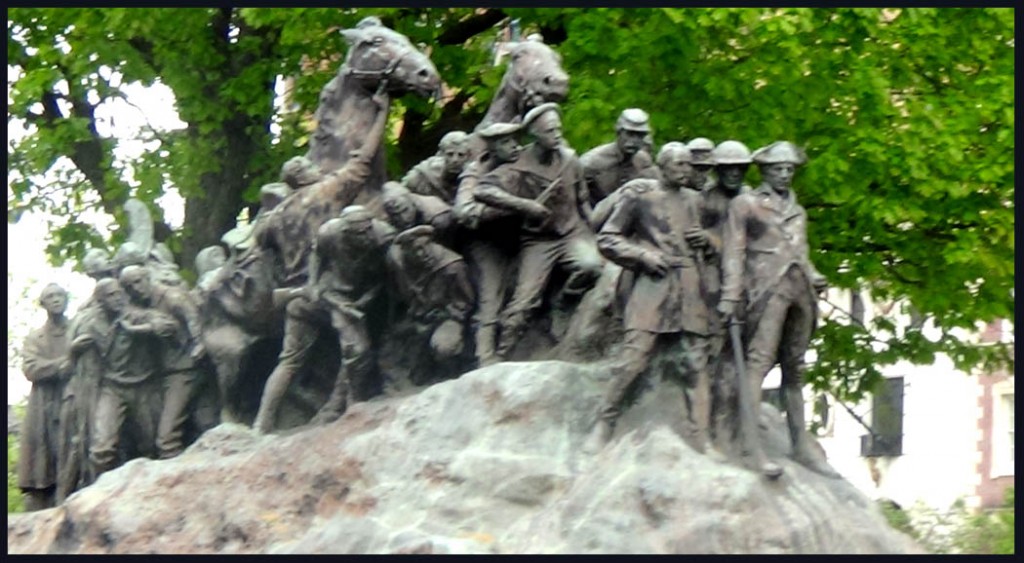

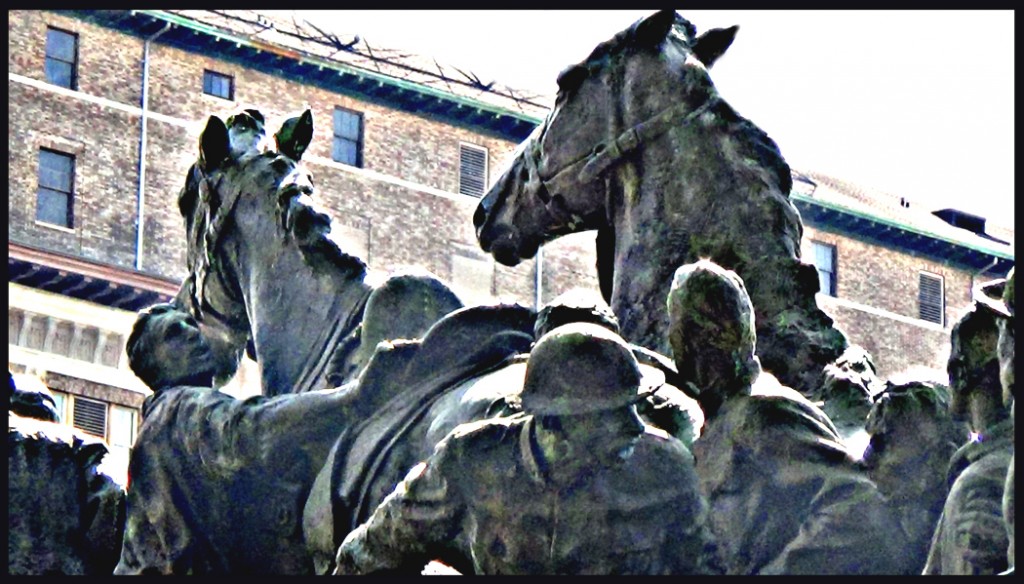

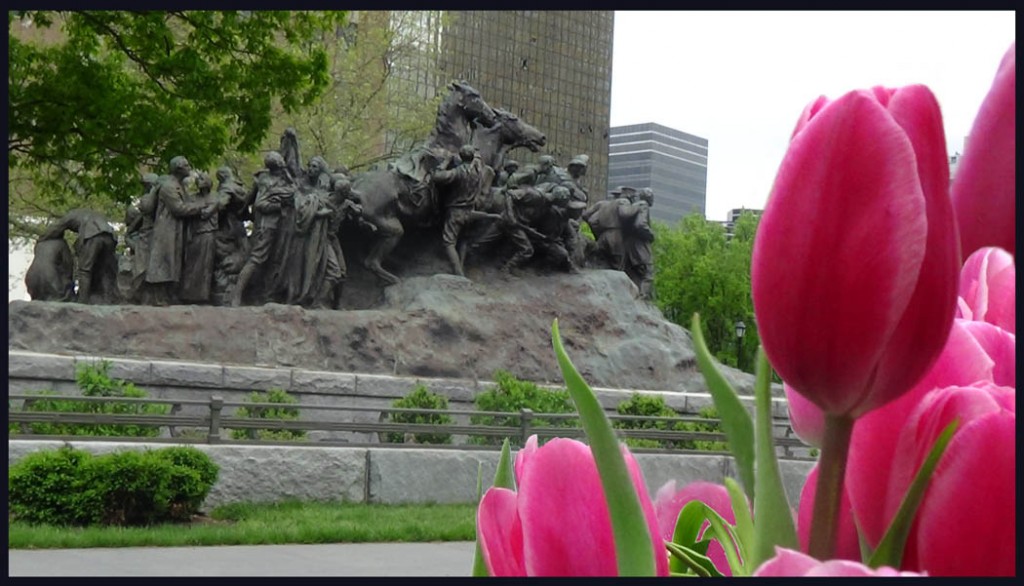

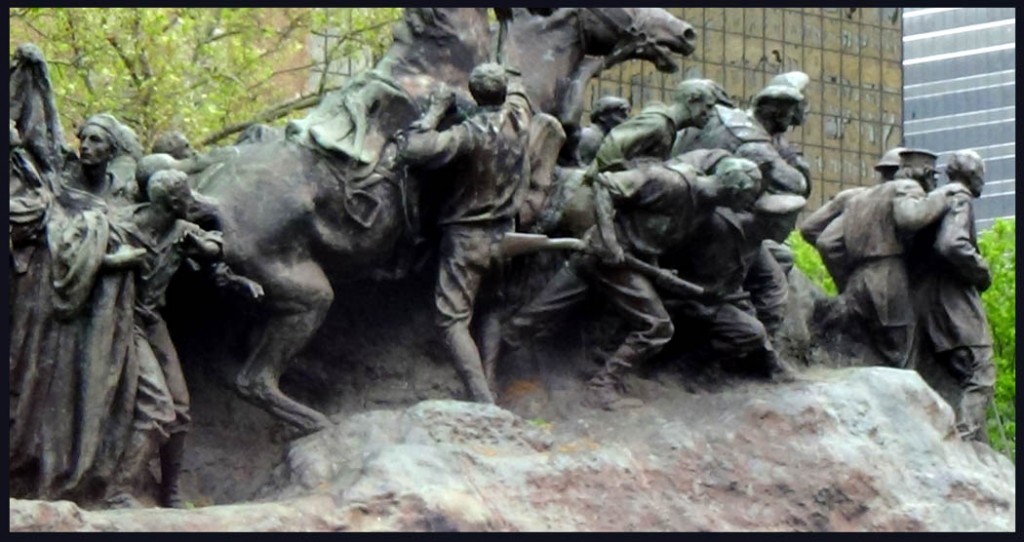

Wars of America is a “colossal” bronze sculpture by Gutzon Borglum containing “forty-two humans and two horses”,[3]located in Military Park, Newark, Essex County, New Jersey, United States. The sculpture sets on a base of granite fromStone Mountain.

Wars of America is a “colossal” bronze sculpture by Gutzon Borglum containing “forty-two humans and two horses”,[3]located in Military Park, Newark, Essex County, New Jersey, United States. The sculpture sets on a base of granite fromStone Mountain.

The sculpture was erected in 1926, eight years after World War I ended, but its intent was broadened to honor all of America’s war dead. In describing it, Borglum said “The design represents a great spearhead. Upon the green field of this spearhead we have placed a Tudor sword, the hilt of which represents the American nation at a crisis, answering the call to arms.”[4]

The sculpture was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 28, 1994.

|

For more information please visit the following link:

The following article is written by Linda Stamato | Star-Ledger Guest Columnist:

https://blog.nj.com/njv_linda_stamato/2015/05/wars_of_america_newarks_triump.html

Wars of America: Newark’s triumphant memorial sculpture

By Linda Stamato | Star-Ledger Guest Columnist

on May 25, 2015 at 11:17 AM, updated May 26, 2015 at 7:07 AM

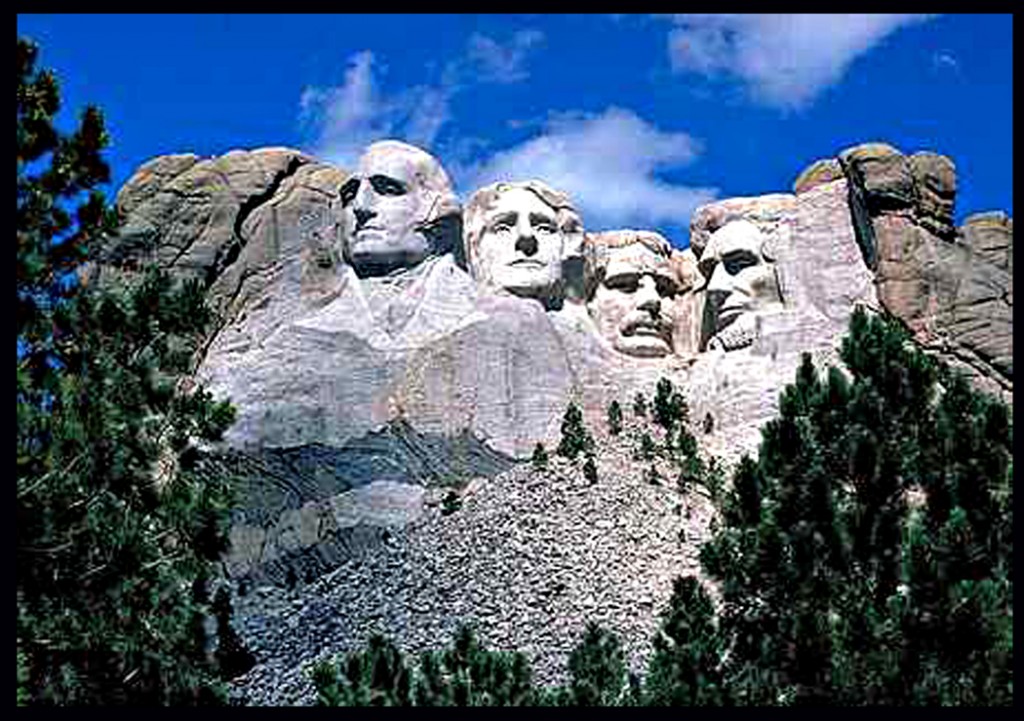

Among Newark’s gems, are the public works of Gutzon Borglum, the extraordinary sculptor whose most famous work, of course, is Mount Rushmore. In Newark, far from South Dakota, and situated downtown, just across from the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, sits one of the most compelling of Borglum’s works: Wars of America. He created this magnificent sculpture over the course of six years, completing it in 1926. It memorializes all the major conflicts in which Americans participated up to and including the First World War.

On Memorial Day it seems more than fitting to reflect on why we build memorials and what this one, in particular, signifies. It was commissioned several years after the end of the World War, but its intent was not solely to honor the courageous men who fought in that war but to honor all of America’s war dead.

The bronze masterpiece consists of forty-two human beings and two horses and commemorates America’s participation in the Revolution, War of 1812; Indian Wars; Mexican War, the Civil War, Spanish American War and World War I.

The bronze masterpiece consists of forty-two human beings and two horses and commemorates America’s participation in the Revolution, War of 1812; Indian Wars; Mexican War, the Civil War, Spanish American War and World War I.

It is in Military Park, which dates back to 1667–when the park was a training ground for soldiers and, later, a drill field for the Colonial and Continental armies–where the colossal Wars of America statue stands in striking relief. It is the centerpiece of the park.

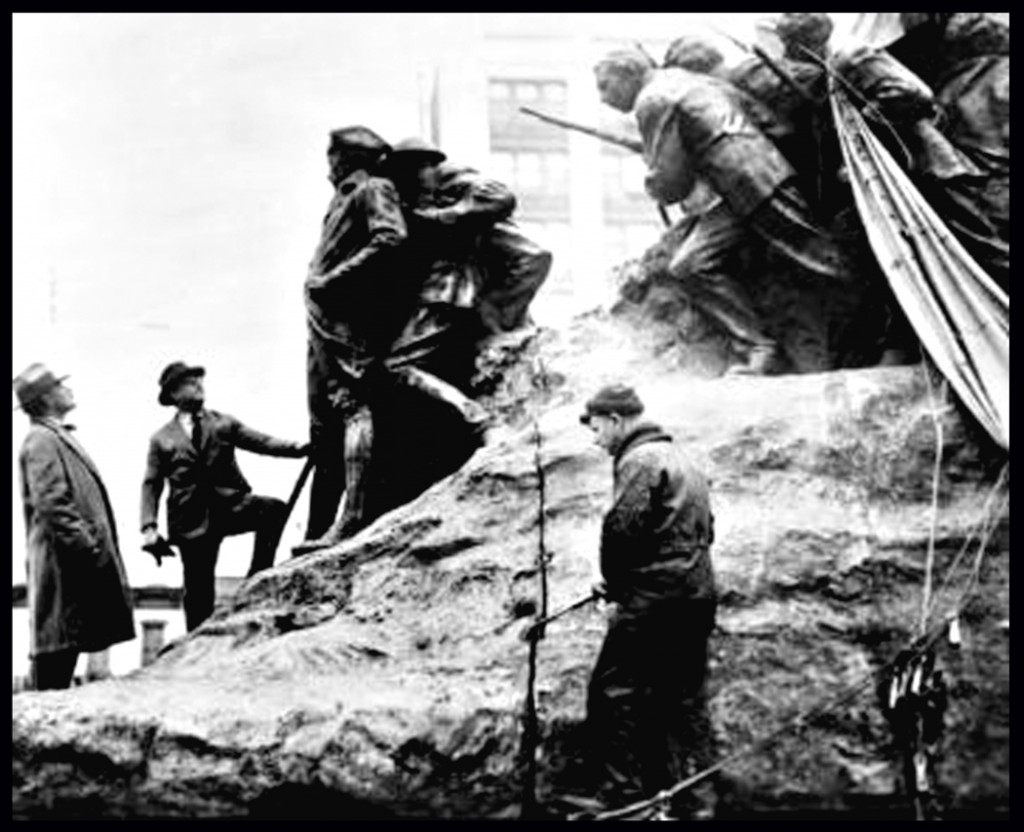

Gutzon Borglum inspecting his sculpture: 1926 Amazon.com

Gutzon Borglum inspecting his sculpture: 1926 Amazon.com

In describing it, Borglum said: “The design represents a great spearhead. Upon the green field of this spearhead we have placed a Tudor sword, the hilt of which represents the American nation at a crisis, answering the call to arms.” (The New York Times; November 7, 1926.)

From John Taliaferro’s “Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to Create Mount Rushmore”:

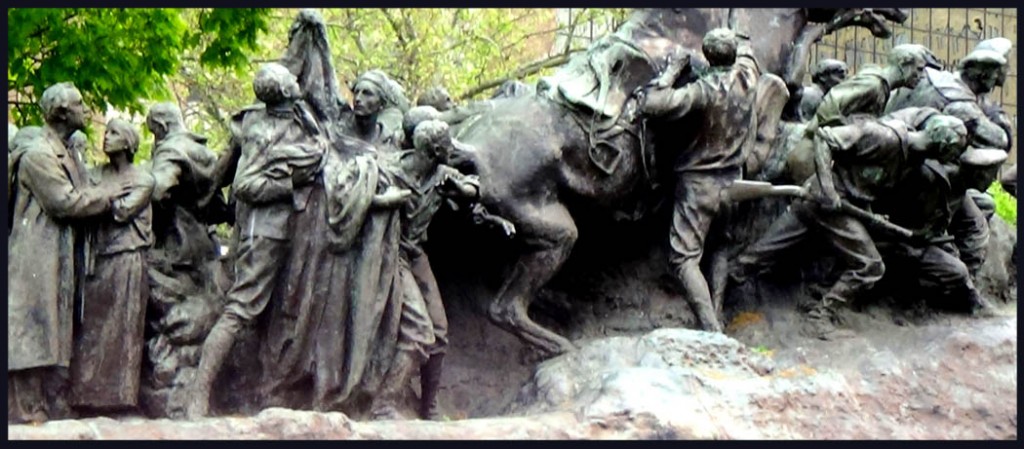

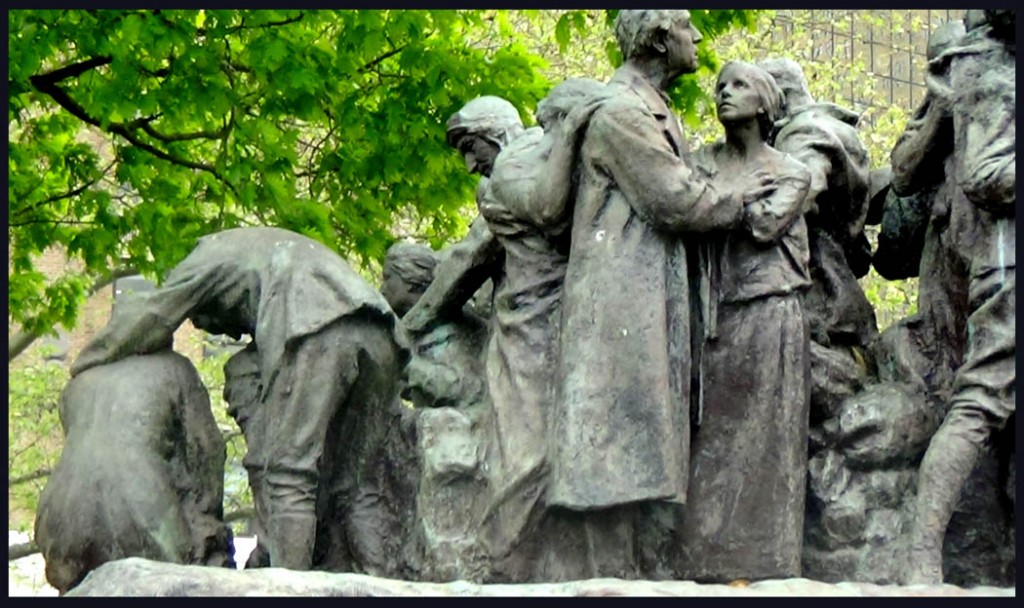

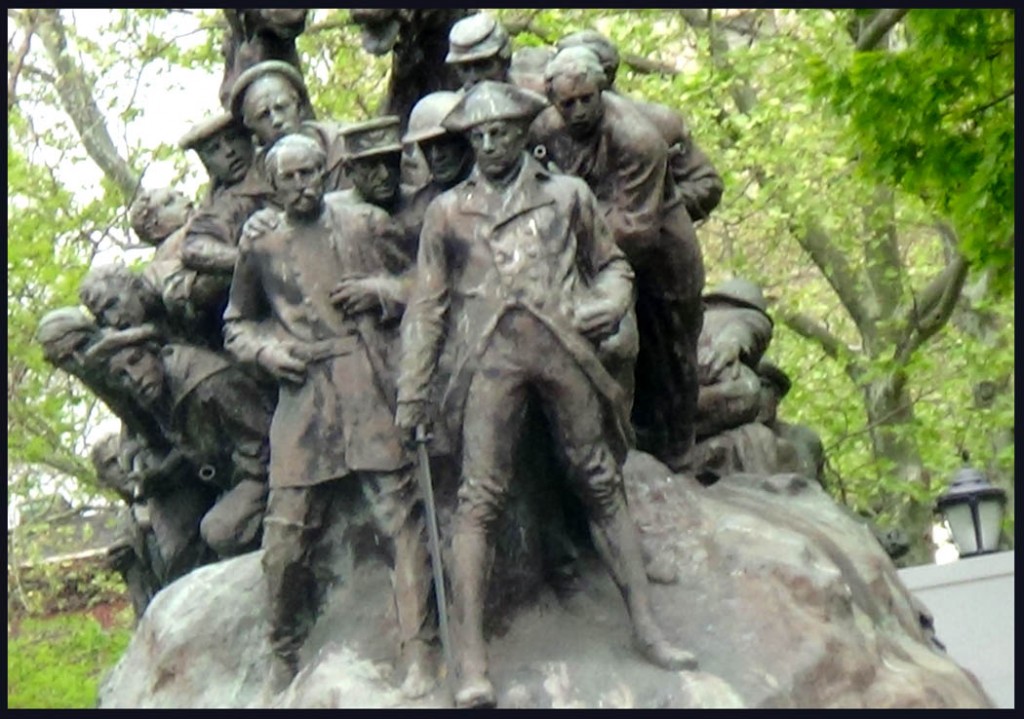

“The statue is fronted by four nameless officers, one dressed in the uniform of the Revolution, one from the union army, one from World War I, and a fourth figure representing the navy. Behind them come thirty-eight more full-size figures, plus two very restive horses. Only a half dozen of the men carry weapons and the Revolutionary officer carries a sword, yet the composition still manages to evoke, in Borglum’s words, ‘an entire nation mobilizing under great pressure of war.’ The group is leaning forward en masse, a concerted thrust of citizen soldiers. Borglum wanted to express the “indignation, fear….physical distress, and pathos “ of war. He achieves all of these and more.”

“Wars” is a brilliant sculpture, that, to Taliaferro, complements all Borglum’s talent and experience. Many of the warriors were actually Borglum’s friends and acquaintances. Easiest to spot are the sculptor himself and his son, Lincoln, depicted halfway down the left flank of the sculpture as the anxious father sends his young son off to battle. His wife, Mary, also appears.

The sculpture represents a“sincere nationalism, with great faith in the United States,” according to Rosa Portell, the curator of theStamford Museum & Nature Center in Connecticut:

The sculpture represents a“sincere nationalism, with great faith in the United States,” according to Rosa Portell, the curator of theStamford Museum & Nature Center in Connecticut:

“Borglum was living in the era of American manifest destiny, when the United States was becoming a world power, and he felt awe for the men who created, preserved and expanded the country.”

The sculpture was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 28, 1994.

Newark has a collection of treasures waiting to be discovered over and over again. Prior to “Wars”, for example, Borglum created three other bronze sculptures that grace the city’s streets and parks: The magnificentSeated Lincoln (in 1911); theIndian and Puritan (in 1916), and a bas-relief, First Landing Party of the Founders of Newark (in 1916.)

It is in art that we capture best, I think, the spirit and courage of the brave people who fought, and those who supported them. War memorials provide symbolic, social and historical experiences that are so compelling that they can impose meaning and order beyond the temporal and chaotic experiences of life. (Ben Barber: Place, Symbol and Utilitarian Functions in War Memorials :1949)

On Memorial Day, especially, Wars of America is a sculpture to visit, to gaze upon and reflect, to give thanks for those who fought and died for the nation. But, it is also just the place to be as we hope the day comes when there is less need for more memorials.

Wars of America: A tribute to those who fought and died for the nation Pam Hasegawa

This is the end of Linda Stamato’s article. Thanks for her article; her conclusion is exactly the way I wish the world to be — “We hope the day comes when there is less need for more memorials”.

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Sunday, May 22, 2016

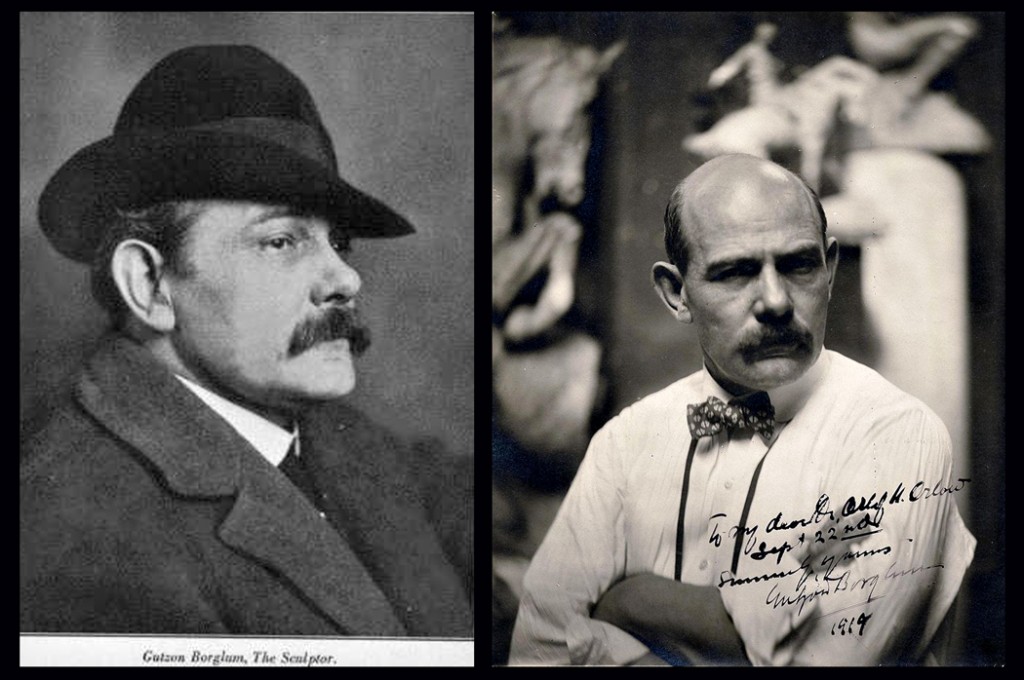

Gutzon Borglum

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gutzon_Borglum

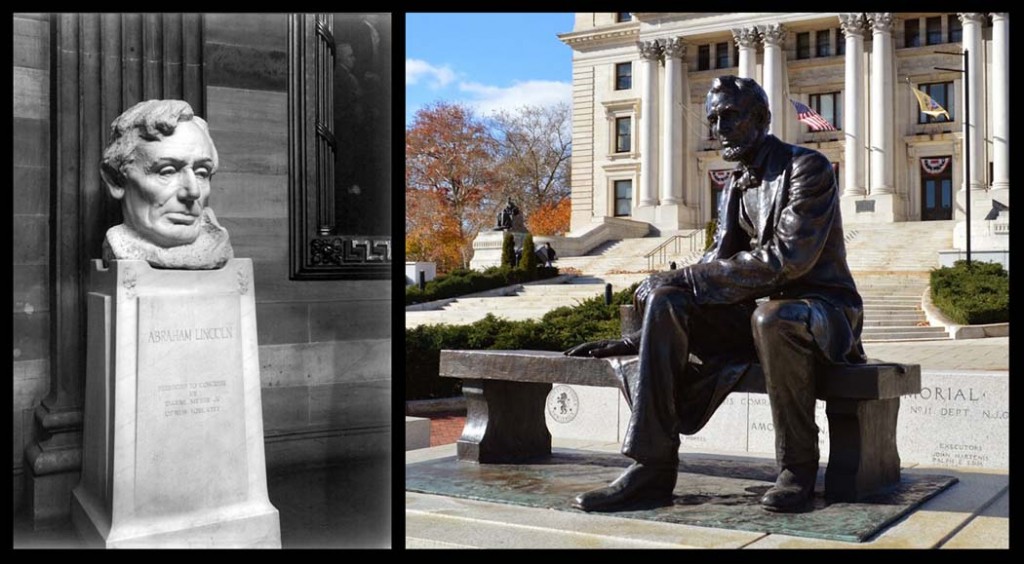

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (March 25, 1867 – March 6, 1941) was an American artist and sculptor. He is most associated with his creation of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial at Mount Rushmore, South Dakota. He was associated with other public works of art, including a bust of Abraham Lincoln exhibited in the White House by Theodore Roosevelt and now held in the United States Capitol Crypt in Washington, D.C..

The son of Danish-American immigrants, Gutzon Borglum was born in 1867 in St. Charles in what was then Idaho Territory. Borglum was a child of Mormon polygamy. His father, Jens Møller Haugaard Børglum (1839-1909), had two wives when he lived in Idaho: Gutzon’s mother, Christina Mikkelsen Borglum (1847-1871) and Gutzon’s mother’s sister, who was Jens’s first wife.[1] Jens Borglum decided to leave Mormonism and moved to Omaha, Nebraska where polygamy was both illegal and taboo; he left Gutzon’s mother and took his first wife with him.[2] Jens Borglum worked mainly as a woodcarver before leaving Idaho to attend the Saint Louis Homeopathic Medical College [3] in Saint Louis, Missouri. Upon his graduation from the Missouri Medical College in 1874, Dr. Borglum moved the family to Fremont, Nebraska, where he established a medical practice. Gutzon Borglum remained in Fremont until 1882, when his father enrolled him in St. Mary’s College, Kansas.[4]

The son of Danish-American immigrants, Gutzon Borglum was born in 1867 in St. Charles in what was then Idaho Territory. Borglum was a child of Mormon polygamy. His father, Jens Møller Haugaard Børglum (1839-1909), had two wives when he lived in Idaho: Gutzon’s mother, Christina Mikkelsen Borglum (1847-1871) and Gutzon’s mother’s sister, who was Jens’s first wife.[1] Jens Borglum decided to leave Mormonism and moved to Omaha, Nebraska where polygamy was both illegal and taboo; he left Gutzon’s mother and took his first wife with him.[2] Jens Borglum worked mainly as a woodcarver before leaving Idaho to attend the Saint Louis Homeopathic Medical College [3] in Saint Louis, Missouri. Upon his graduation from the Missouri Medical College in 1874, Dr. Borglum moved the family to Fremont, Nebraska, where he established a medical practice. Gutzon Borglum remained in Fremont until 1882, when his father enrolled him in St. Mary’s College, Kansas.[4]

After a brief stint at Saint Mary’s College, Gutzon Borglum relocated to Omaha, Nebraska, where he apprenticed in a machine shop and graduated from Creighton Preparatory School. He was trained in Paris at the Académie Julian, where he came to know Auguste Rodin and was influenced by Rodin’s impressionistic light-catching surfaces. Back in the U.S. in New York City he sculpted saints and apostles for the new Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in 1901; in 1906 he had a group sculpture accepted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art[5]— the first sculpture by a living American the museum had ever purchased—and made his presence further felt with some portraits. He also won the Logan Medal of the Arts. His reputation soon surpassed that of his younger brother, Solon Borglum, already an established sculptor.

After a brief stint at Saint Mary’s College, Gutzon Borglum relocated to Omaha, Nebraska, where he apprenticed in a machine shop and graduated from Creighton Preparatory School. He was trained in Paris at the Académie Julian, where he came to know Auguste Rodin and was influenced by Rodin’s impressionistic light-catching surfaces. Back in the U.S. in New York City he sculpted saints and apostles for the new Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in 1901; in 1906 he had a group sculpture accepted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art[5]— the first sculpture by a living American the museum had ever purchased—and made his presence further felt with some portraits. He also won the Logan Medal of the Arts. His reputation soon surpassed that of his younger brother, Solon Borglum, already an established sculptor.

In 1925, the sculptor moved to Texas to work on the monument to trail drivers commissioned by the Trail Drivers Association. He completed the model in 1925, but due to lack of funds it was not cast until 1940, and then was only a fourth its originally planned size. It stands in front of the Texas Pioneer and Trail Drivers Memorial Hall next to the Witte Museum in San Antonio. Borglum lived at the historic Menger Hotel, which in the 1920s was the residence of a number of artists. He subsequently planned the redevelopment of the Corpus Christi waterfront; the plan failed,[why?] although a model for a statue of Christ intended for it was later modified by his son and erected on a mountaintop in South Dakota. While living and working in Texas, Borglum took an interest in local beautification. He promoted change and modernity, although he was berated by academicians.[6]

In 1925, the sculptor moved to Texas to work on the monument to trail drivers commissioned by the Trail Drivers Association. He completed the model in 1925, but due to lack of funds it was not cast until 1940, and then was only a fourth its originally planned size. It stands in front of the Texas Pioneer and Trail Drivers Memorial Hall next to the Witte Museum in San Antonio. Borglum lived at the historic Menger Hotel, which in the 1920s was the residence of a number of artists. He subsequently planned the redevelopment of the Corpus Christi waterfront; the plan failed,[why?] although a model for a statue of Christ intended for it was later modified by his son and erected on a mountaintop in South Dakota. While living and working in Texas, Borglum took an interest in local beautification. He promoted change and modernity, although he was berated by academicians.[6]

A fascination with gigantic scale and themes of heroic nationalism suited his extroverted personality. His head of Abraham Lincoln, carved from a six-ton block of marble, was exhibited in Theodore Roosevelt‘s White House and can be found in the United States Capitol Crypt in Washington, D.C. A “patriot,” believing that the “monuments we have built are not our own,” he looked to create art that was “American, drawn from American sources, memorializing American achievement,” according to a 1908 interview article. Borglum was highly suited to the competitive environment surrounding the contracts for public buildings and monuments, and his public sculpture is sited all around the United States.

A fascination with gigantic scale and themes of heroic nationalism suited his extroverted personality. His head of Abraham Lincoln, carved from a six-ton block of marble, was exhibited in Theodore Roosevelt‘s White House and can be found in the United States Capitol Crypt in Washington, D.C. A “patriot,” believing that the “monuments we have built are not our own,” he looked to create art that was “American, drawn from American sources, memorializing American achievement,” according to a 1908 interview article. Borglum was highly suited to the competitive environment surrounding the contracts for public buildings and monuments, and his public sculpture is sited all around the United States.

In 1908, Borglum won a competition for a statue of the Civil War General Philip Sheridan to be placed in Sheridan Circle in Washington. D.C. A second version of General Philip Sheridan was erected in Chicago, Illinois, in 1923. Winning this competition was a personal triumph for him because he won out over sculptor J.Q.A.Ward, a much older and more established artist and one whom Borglum had clashed with earlier in regard to the National Sculpture Society. At the unveiling of the Sheridan statue, one observer, President Theodore Roosevelt (whom Borglum was later to include in the Mount Rushmore portrait group), declared that it was “first rate;” a critic wrote that “as a sculptor Gutzon Borglum was no longer a rumor, he was a fact.” (Smith:see References)

In 1908, Borglum won a competition for a statue of the Civil War General Philip Sheridan to be placed in Sheridan Circle in Washington. D.C. A second version of General Philip Sheridan was erected in Chicago, Illinois, in 1923. Winning this competition was a personal triumph for him because he won out over sculptor J.Q.A.Ward, a much older and more established artist and one whom Borglum had clashed with earlier in regard to the National Sculpture Society. At the unveiling of the Sheridan statue, one observer, President Theodore Roosevelt (whom Borglum was later to include in the Mount Rushmore portrait group), declared that it was “first rate;” a critic wrote that “as a sculptor Gutzon Borglum was no longer a rumor, he was a fact.” (Smith:see References)

Borglum was active in the committee that organized the New York Armory Show of 1913, the birthplace of modernism in American art. By the time the show was ready to open, however, Borglum had resigned from the committee, feeling that the emphasis on avant-garde works had co-opted the original premise of the show and made traditional artists like himself look provincial. He lived in Stamford, Connecticut for 10 years.

Borglum was active in the committee that organized the New York Armory Show of 1913, the birthplace of modernism in American art. By the time the show was ready to open, however, Borglum had resigned from the committee, feeling that the emphasis on avant-garde works had co-opted the original premise of the show and made traditional artists like himself look provincial. He lived in Stamford, Connecticut for 10 years.

Borglum was an active member of the Ancient Free and Accepted Masons (the Freemasons), raised in Howard Lodge #35, New York City, on June 10, 1904, and serving as its Worshipful Master 1910-11. In 1915, he was appointed Grand Representative of the Grand Lodge of Denmark near the Grand Lodge of New York. He received his Scottish Rite Degrees in the New York City Consistory on October 25, 1907.[7]

Borglum was an active member of the Ancient Free and Accepted Masons (the Freemasons), raised in Howard Lodge #35, New York City, on June 10, 1904, and serving as its Worshipful Master 1910-11. In 1915, he was appointed Grand Representative of the Grand Lodge of Denmark near the Grand Lodge of New York. He received his Scottish Rite Degrees in the New York City Consistory on October 25, 1907.[7]

Borglum was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.[8] He was one of the six knights who sat on the Imperial Koncilium in 1923, which transferred leadership of the Ku Klux Klan from Imperial Wizard Colonel Simmons to Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans.[9] In 1925, having only completed the head of Robert E. Lee, Borglum was dismissed from the Stone Mountain project, with some holding that it came about due to infighting within the KKK, with Borglum involved in the strife.[10] Later, he stated, “I am not a member of the Kloncilium, nor a knight of the KKK’”, but Howard and Audrey Shaff add that, “that was for public consumption.”[11] The museum at Mount Rushmore displays a letter to Borglum from D. C. Stephenson, the infamous Klan Grand Dragon who was later convicted of the rape and murder of Madge Oberholtzer. The 8×10 foot portrait contains the inscription, “To my good friend Gutzon Borglum, with the greatest respect”. Correspondence from Borglum to Stephenson during the 1920s detailed a deep racist conviction in Nordic moral superiority, and urges strict immigration policies.[12]

Borglum was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.[8] He was one of the six knights who sat on the Imperial Koncilium in 1923, which transferred leadership of the Ku Klux Klan from Imperial Wizard Colonel Simmons to Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans.[9] In 1925, having only completed the head of Robert E. Lee, Borglum was dismissed from the Stone Mountain project, with some holding that it came about due to infighting within the KKK, with Borglum involved in the strife.[10] Later, he stated, “I am not a member of the Kloncilium, nor a knight of the KKK’”, but Howard and Audrey Shaff add that, “that was for public consumption.”[11] The museum at Mount Rushmore displays a letter to Borglum from D. C. Stephenson, the infamous Klan Grand Dragon who was later convicted of the rape and murder of Madge Oberholtzer. The 8×10 foot portrait contains the inscription, “To my good friend Gutzon Borglum, with the greatest respect”. Correspondence from Borglum to Stephenson during the 1920s detailed a deep racist conviction in Nordic moral superiority, and urges strict immigration policies.[12]

Borglum died in 1941 and is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale in California in the Memorial Court of Honor. His second wife, Mary Montgomery Williams Borglum, 1874–1955 (they were married May 20, 1909), is interred alongside him. In addition to his son, Lincoln, he had a daughter, Mary Ellis (Mel) Borglum Vhay (1916–2002).

Borglum was initially involved in the carving of Stone Mountain in Georgia. Borglum’s nativist stances made him seem an ideologically sympathetic choice to carve a memorial to heroes of the Confederacy, planned for Stone Mountain, Georgia. In 1915, he was approached by the United Daughters of the Confederacy with a project for sculpting a 20-foot (6 m) high bust of General Robert E. Lee on the mountain’s 800-foot (240 m) rockface. Borglum accepted, but told the committee, “Ladies, a twenty foot head of Lee on that mountainside would look like a postage stamp on a barn door.’”[13]

Borglum’s ideas eventually evolved into a high-relief frieze of Lee, Jefferson Davis, and ‘Stonewall’ Jackson riding around the mountain, followed by a legion of artillery troops. Borglum agreed to include a Ku Klux Klan altar in his plans for the memorial to acknowledge a request of Helen Plane in 1915, who wrote to him: “I feel it is due to the KKK that saved us from Negro domination and carpetbag rule, that it be immortalized on Stone Mountain”.[10]

After a delay caused by World War I, Borglum and the newly chartered Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association set to work on this unexampled monument, the size of which had never been attempted before. Many difficulties slowed progress, some because of the sheer scale involved. After finishing the detailed model of the carving, Borglum was unable to trace the figures onto the massive area on which he was working, until he developed a gigantic magic lantern to project the image onto the side of the mountain.

Carving officially began on June 23, 1923, with Borglum making the first cut. At Stone Mountain he developed sympathetic connections with the reorganized Ku Klux Klan, who were major financial backers for the monument. Lee’s head was unveiled on Lee’s birthday January 19, 1924, to a large crowd, but soon thereafter Borglum was increasingly at odds with the officials of the organization. His domineering, perfectionist, authoritarian manner brought tensions to such a point that in March 1925 Borglum smashed his clay and plaster models. He left Georgia permanently, his tenure with the organization over. None of his work remains, as it was all cleared from the mountain’s face for the work of Borglum’s replacement Henry Augustus Lukeman. In in his abortive attempt, Borglum had developed necessary techniques for sculpting on a gigantic scale that made Mount Rushmore possible.[14]

His Mount Rushmore project, 1927–1941, was the brainchild of South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson. His first attempt with the face of Thomas Jefferson was blown up after two years. Dynamite was also used to remove large areas of rock from under Washington’s brow. The initial pair of presidents, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson was soon joined by Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt.

Ivan Houser , father of John Sherrill Houser, was assistant sculptor to Gutzon Borglum in the early years of carving; he began working with Borglum shortly after the inception of the monument and was with Borglum for a total of seven years. When Houser left Gutzon to devote his talents to his own work, Gutzon’s son, Lincoln, took over as Assistant-Sculptor to his father.

Borglum alternated exhausting on-site supervising with world tours, raising money, polishing his personal legend, sculpting a Thomas Paine memorial for Paris and a Woodrow Wilson one for Pozna?, Poland (1931).[15] In his absence, work at Mount Rushmore was overseen by his son, Lincoln Borglum. During the Rushmore project, father and son were residents of Beeville, Texas. When he died in Chicago, following complications after surgery, his son finished another season at Rushmore, but left the monument largely in the state of completion it had reached under his father’s direction.

In 1908, Borglum completed the statue of Comstock Lode silver baron John William Mackay (1831–1902). The statue is located at the University of Nevada, Reno.

In 1909, the sculpture Rabboni was created as a grave site for the Ffoulke Family in Washington, D.C. at Rock Creek Cemetery. [16]

In 1912, the Nathaniel Wheeler Memorial Fountain was dedicated in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

In 1912, the Nathaniel Wheeler Memorial Fountain was dedicated in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

In 1918, he was one of the drafters of the Czechoslovak declaration of independence.[17]

One of Borglum’s more unusual pieces is the Aviator completed in 1919 as a memorial for James R. McConnell, who was killed in World War I while flying for the Lafayette Escadrille. It is located on the grounds of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia.[18]

Four public works by Borglum are in Newark, NJ: Seated Lincoln (1911), Indian and Puritan (1916), Wars of America (1926), and a bas-relief, First Landing Party of the Founders of Newark (1916).[19]

Four public works by Borglum are in Newark, NJ: Seated Lincoln (1911), Indian and Puritan (1916), Wars of America (1926), and a bas-relief, First Landing Party of the Founders of Newark (1916).[19]

Borglum sculpted the memorial Start Westward of the United States, which is located in Marietta, Ohio (1938).

Borglum sculpted the memorial Start Westward of the United States, which is located in Marietta, Ohio (1938).

He built the statue of Daniel Butterfield at Sakura Park in Manhattan (1918).[20]

He created a memorial to Sacco and Vanzetti (1928), a plaster cast of which is now in the Boston Public Library.[21]

Another Borglum design is the North Carolina Monument on Seminary Ridge at the Gettysburg Battlefield in south-central Pennsylvania. The cast bronze sculpture depicts a wounded Confederate officer encouraging his men to push forward during Pickett’s Charge. Borglum had also made arrangements for an airplane to fly over the monument during the dedication ceremony on July 3, 1929. During the sculpture’s unveiling, the plane scattered roses across the field as a salute to those North Carolinians who had fought and died at Gettysburg.

Popular culture[edit]

Popular culture[edit]

- Canadian artist Christian Cardell Corbet was the first Canadian to sculpt a posthumous medallion of Borglum. It currently resides at the Gutzon Borglum Museum in South Dakota.

- Historian Simon Schama, in his Landscape and Memory, discusses Borglum’s life and work.[22]

- Borglum is a prominent character in the 2010 novel, Black Hills, by Dan Simmons.

- The October 19, 2011 episode of Brad Meltzer’s Decoded examines a conspiracy theory that Mount Rushmore was actually a white supremacy monument built for Borglum’s KKK contacts.

Publications[edit]

- Borglum, Gutzon (June 1914). “Art That Is Real And American: Why We Should Create Our Own Art out Of Our Own National History Instead Of Imitating The Work That Properly Expressed The Triumphs Of Greece And Rome”. The World’s Work: A History of Our Time XLIV (2): 200–215. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

The following article is from PBS, American Experience: Biography Rushmore-Borglum

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/rushmore-borglum/

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum liked to tinker with his own legend, subtracting a few years from his age, changing the story of his parentage. The best archival research has revealed that he was born in 1867 to one of the wives of a Danish Mormon bigamist. When his father decided to conform to societal norms that were pressing westward with the pioneers, he abandoned Gutzon’s mother, and remained married to his first wife, her sister.

In 1884, when Gutzon was 16, the family moved to Los Angeles. His father, unhappy in California, soon returned to Nebraska, but Gutzon stayed behind. He studied art and met Elizabeth Jaynes Putnam, a painter and divorcee 18 years his senior. Lisa Putnam became a teacher and mentor to Gutzon, helping manage his career and advising his education. They were married in 1889. While in California, Gutzon painted a portrait of General John C. Fremont and learned the value of having a wealthy and socially connected patron. Although the general died a few years after sitting for his painting, his widow provided Borglum with contacts to men such as Leland Stanford and Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1884, when Gutzon was 16, the family moved to Los Angeles. His father, unhappy in California, soon returned to Nebraska, but Gutzon stayed behind. He studied art and met Elizabeth Jaynes Putnam, a painter and divorcee 18 years his senior. Lisa Putnam became a teacher and mentor to Gutzon, helping manage his career and advising his education. They were married in 1889. While in California, Gutzon painted a portrait of General John C. Fremont and learned the value of having a wealthy and socially connected patron. Although the general died a few years after sitting for his painting, his widow provided Borglum with contacts to men such as Leland Stanford and Theodore Roosevelt.

The Borglums traveled to Paris to work and study, and there Gutzon met sculptor Auguste Rodin. As much as he admired Rodin, more than one historian has suggested that the reason Gutzon gave up painting was to compete with his brother Solon, who had been making his name as a sculptor. Gutzon’s talent was immediately apparent and he found a few commissions (certainly the fact that Solon had already associated the name Borglum with fine sculpture didn’t hurt). At the same time, Gutzon’s marriage was falling apart. He left Paris alone in 1901 and aboard ship met Mary Montgomery, an American who had just completed her doctorate at the University of Berlin. He and Mary wed as soon as Lisa granted him a divorce. They bought a house and farm in Connecticut and named it “Borgland.”

Borglum’s major work back in America included a bust of Abraham Lincoln, which he was able to exhibit in Theodore Roosevelt’s White House. The Lincoln portrait and other much admired works gave Borglum a national reputation, and he was invited by Helen Plane of the United Daughters of the Confederacy to some of the techniques that would later be used on Rushmore.

While at Stone Mountain, Borglum became associated with the newly reborn Ku Klux Klan. Whether this accorded with a racist world view, or if it was simply one way to bond with some of his patrons on the Stone Mountain project, is unclear. Frankly, Borglum had little time for anyone, white or black, who was not a Congressman or millionaire, or happened to be in his way. There is no indication, for example, that he treated his long-suffering black chauffeur Charlie Johnson any differently than any white employee — he owed him back pay just like everyone else. Stone Mountain was not finished by Borglum, but it inspired his next job: Mount Rushmore.

When South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson read about Stone Mountain, he invited Borglum out to the Black Hills of South Dakota to create a monument there. Borglum, perhaps realizing that Stone Mountain had only regional support, immediately suggested a national subject for Rushmore: Presidents George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. Theodore Roosevelt and Thomas Jefferson were added to the program soon afterward. Borglum had met and campaigned for Roosevelt, and by invoking that president’s acquisition of the Panama Canal and Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase, the Rushmore monument became a story of the expansion of the United States, the embodiment of Manifest Destiny.

Work on the mountain was not constantly supervised by Borglum. When he was at Rushmore, Borglum would be climbing all over the mountain and all over the hills, to determine the best angle for each feature, and advising the carvers on how to create the nuanced details that might not even be visible from below. But after creating the models, siting the sculpture, and developing methods for transferring the image to the mountain and carving the rock, there were long periods during which Borglum’s presence was not required. He would often leave his assistants, including his son Lincoln, to supervise the work and then travel. He would go to Washington, D.C. to lobby for more money, and he also traveled around the world, finding and completing other commissions, sculpting a Thomas Paine for Paris and a Woodrow Wilson (for Poland, and meeting politicians and celebrities such as Helen Keller. (Helping her feel pieces by his old friend Rodin, he recalled her comment: “Meeting you is like a visit from the gods.” He sometimes felt the same way about himself, writing in his journal: “I must see, think, feel and draw in Thor’s dimension.”) When he returned to the Dakotas, a rock might have been roughly blasted into an egg shape and he would be back to looking over every detail.

Borglum’s stubborn insistence on having things done his way led to numerous confrontations with John Boland, who chaired the executive committee of the Mount Rushmore Commission. His temper and perfectionism caused him to fire his best workmen (who then had to be hired back by Borglum’s son Lincoln). Borglum’s ambition and hubris motivated him to recreate a landscape in his image (a tableau of prominent white men) rather than for the Native Americans who held the Black Hills sacred. Borglum was stubborn, insistent, temperamental, perfectionist, high-reaching, and proud — but these were also the characteristics that were required to carve a mountain. Big, brash, almost larger than life, only a man like Gutzon Borglum could have conceived of and created the monument on Mount Rushmore.

On March 6, 1941, Borglum died, following complications after surgery. His son finished another season

at Rushmore, but left the monument largely in the state of completion it had reached under his father’s

direction.

“Beauty is like a soul that hovers over the surface of form. Its presence is unmistakable in Art or in Life. The measure of its revelation depends on the measure of our own soul- consciousness, the boundaries of our own spirit.” — Gutzon Borglum

Before he created Mount Rushmore, Gutzon Borglum already had a productive and successful career as an artist.

The Stamford Museum and Nature Center organized a 1999 exhibition titled “Out of Rushmore’s Shadow: The Artistic Development of Gutzon Borglum (1867-1941).” Selections from that exhibit illustrate some of the influences Borglum incorporated into his work. Frequently, Borglum favored muscular, dynamic poses for his subjects, and he also liked to make art on a large scale.

The following article is written by Mark Di Ionno | The Star-Ledger The Star-Ledger

on February 16, 2009 at 8:34 PM, updated September 01, 2009 at 2:52 PM

https://blog.nj.com/njv_mark_diionno/2009/02/four_score_and_18_years_ago_sc.html

Four score and 18 years ago, sculptor left his mark on Newark

In this, the season of presidents, the story of Mount Rushmore is often retold. It took 14 years and 400 men to carve in stone the vision of sculptor Gutzon Borglum. A sheer mountain face of South Dakota’s granite Black Hills was shaped into a 60-foot-high monument to four great American presidents.

Borglum, born in Idaho two years after Abraham Lincoln’s death, had believed in creating art “drawn from American sources, memorializing American achievement,” he said in 1908.

Borglum’s public works reflected his sense of a big, expansive America. They were grand in scale, not absorbed by either the cityscapes of the Northeast or the mountains of the West.

Two works of such magnitude are here in Newark: “Seated Lincoln” in front of the Essex County Historic Courthouse, and “Wars of America,” the centerpiece of Military Park.

There are also two smaller Borglums in the city. A stone sculpture, known as “Puritan and Indian,” is on the north end of Washington Park, and a marble relief carving of the founding of Newark is on Saybrook Place.

Long before Mount Rushmore, Borglum exercised his artist’s vision of “American achievement” here.

“He had a sincere nationalism, with great faith in the United States,” said Rosa Portell, the curator of the Stamford Museum & Nature Center in Connecticut. Borglum had his studio in Stamford, and the museum has a large Borglum collection.

“He was living in the era of American manifest destiny, when the United States was becoming a world power, and he felt awe for the men who created, preserved and expanded the country.”

In this season of presidents, the 200th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln is being celebrated. Perhaps no other artist is as closely associated with Lincoln’s image as Borglum.

“He was dedicated and devoted to Lincoln,” Portell said. “He named his son Lincoln. He studied every available image of Lincoln, and had his own death mask made.”

His “Colossal Lincoln” was commissioned by Teddy Roosevelt and now sits in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

“The images of Lincoln that impressed him the most were of the anguish on his face when he was getting the daily casualty reports from the battlefields,” Portell said. “He would go the White House gardens to hear these reports, and they impacted him deeply. The Newark statue, I believe, reflects that anguish.”

“Seated Lincoln” was commissioned 100 years ago by a group of Newark citizens for the century anniversary of Lincoln’s birth. (A wealthy Newark resident, Civil War veteran Amos Hoaglund Van Horn, contributed $250,000 for both Lincoln and the “Wars of America.”)

President Theodore Roosevelt came to dedicate “Seated Lincoln” on Memorial Day 1911, as thousands jammed the streets around the new courthouse.

Newark in the Gilded Age was a place of such wealth and prestige, it attracted the day’s greatest names in American public art and architecture.

Cass Gilbert, most famous for New York’s Woolworth Building, designed the Essex courthouse.

Stanford White, builder of the Washington Square Arch, the second Madison Square Garden and the New York Herald Building, did the High Street mansion of brewer Christian Feigenspan.

Landscape architect John Charles Olmsted, the son of Frederick Law Olmsted, laid out Branch Brook and Weequahic parks.

“Newark was the kind of city where wealth accumulated, but instead of buying art for their own salons, the wealthy sponsored public art,” Portell said. “That is a spirit the community should always treasure.”

Borglum’s granddaughter, Robin Borglum Carter, who lives in Corpus Christi, Texas, remembers coming to Newark “many, many years ago” to see the sculptures. She has photos of them in her book, “Gutzon Borglum: His Life and Works.”

Love Birds

“Seated Lincoln,” she said, is one of his best works. Maybe the best. And agrees with Portell that both “Seated Lincoln” and “Wars of America” are among the very best of Borglum’s inventory. Portells put them in the top five, and Carter says, “Absolutely.”

But “Wars of America” has a sentimental value to Carter, too.

In the faces of the soldiers and their families, Gutzon Borglum put himself, his wife, Mary, and son, Lincoln.

“I see my father (Lincoln), my grandfather and grandmother,” she said. “I think that’s why I’m so fond of it.”

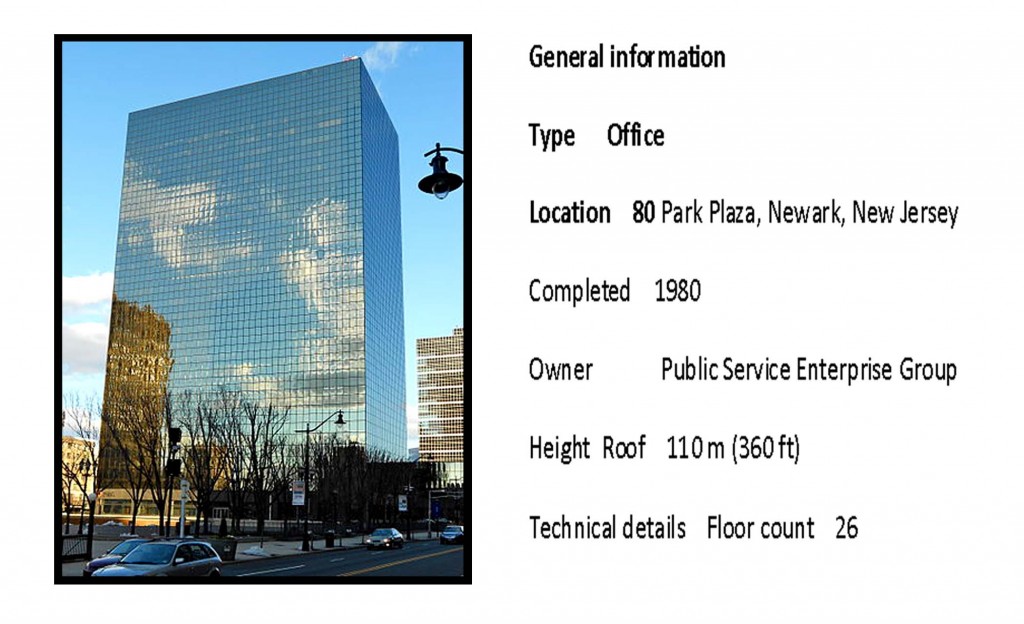

Public Service Electric and Gas Company’s Head Quarter (PSE&G HQ)

All these glass buildings are great. They act like canvases with artwork. The artwork is changing every minute with time and climate, painting the image of the reality of sky and surrounding area at the vicinity of specific buildings.

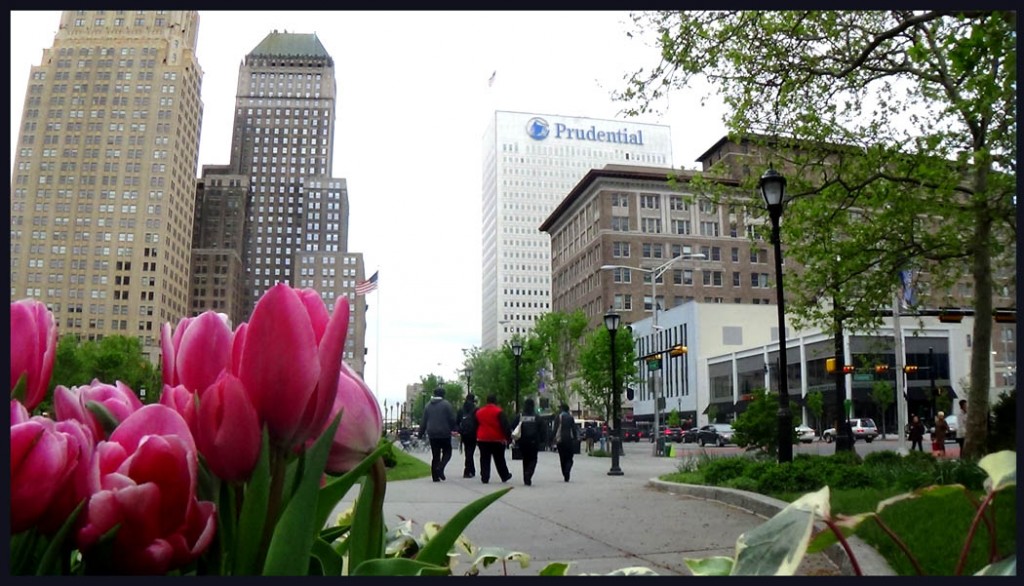

Prudential Tower, Newark, New Jersey

I wonder why?????

These corporations such as PSE&G and Prudential are so prosperous. They are able to build huge fancy buildings. They get richer and bigger and bigger every year. But the majority of customers who pay for gas and electric or insurance are saving every penny to pay for these bills. There are so many homeless in every city and town. These corporations are so smart to make good profit from millions of customers. These millions of customers have to check their bills for the increasing rates every year.

I think these corporations should give their customers some reduction instead of increasing rates. They can build houses for the homeless or give out food to needy people. Fairness is the name of the game. If more and more people cannot pay for gas and electric or insurance bills these companies are going to lose their customers anyhow. Corporations should run their business to serve people rather than greedily taking all that they can.

Balance and fairness helps society go on smoothly so that peace and harmony can be with everyone.

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Sunday, May 22, 2016, 3:35 A.M.

Students having pizza after school in the park

Students having pizza after school in the park

Gutzon Borglum, The Sculptor (March 25, 1867 – March 6, 1941)

Below are some of Gutzon Borglum’s sculptures

1 Memorial to Charles Brantley Aycock, Noth Carolina State Capitol (1941)

2 Thomas Paine, Montsouris, Paris (1936)

3 Memorial to Henry Lawson Wyatt, North Carolina State Capitol (1912)

4 Rabboni, Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D. C. (1909)

5 Statue of John Peter Altgeld, Lincoln Park, Chicago (1915)

6 Statue of John William Mackay, Mackay School of Earth Sciences and Engineering (1908)

7 General Philip Sheridan, sculpted by Borglum in 1908, in Washington, D.C.

8 Stone Mountain located near Atlanta, Georgia

9 Monument depicting North Carolinian soldiers at the Battle of Gettysburg

Mount Rushmore located in the Black Hills of South Dakota

Mount Rushmore located in the Black Hills of South Dakota

Left: Bust of Abraham Lincoln, Crypt of the U.S. Capitol (1908)

Left: Bust of Abraham Lincoln, Crypt of the U.S. Capitol (1908)

Right: Seated Lincoln is a memorial sculpture by Gutzon Borglum located next to the Essex County Courthouse in Newark, Essex County, New Jersey, United States. The bronze sculpture of Abraham Lincoln seated at one end of a bench was dedicated by President Theodore Roosevelt on Memorial Day 1911.[3]

Gutzon Borglum with his Colossal Lincoln, The Borglum Archives

“Among the heroes being celebrated in public monuments, few were as prevalent as Abraham Lincoln. His popularity was particularly strong around 1909, the centenary of his birth. Artists vied with each other trying to prove that their version of Lincoln was the best. In 1907 Borglum had made a colossal head of Lincoln which, at Teddy Roosevelt’s urging, was shown at the White House and eventually donated to the United States Capitol Building by Eugene Meyer. Much admired by Lincoln’s son, Robert, this sculpture helped cement Borglum’s reputation as a monumental sculptor.”

| Public Service Enterprise Group Inc.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_Service_Enterprise_Group

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

|

| Public | |

| NYSE: PEG S&P 500 Component Dow Jones Utility Average component |

|

|

Industry |

Utilities |

|

Founded |

1903 |

|

Headquarters |

Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

|

Key people |

Ralph Izzo (Pres., CEO) Caroline Dorsa (EVP, CFO) |

|

Revenue |

|

|

Number of employees |

10,352 (2009)[2] |

| PSE&G, PSEG Power, PSEG Energy Holdings |

|

|

Website |

www.pseg.com |

Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG), founded as the Public Service Corporation of New Jersey and later renamed Public Service Electric and Gas Company (PSE&G), is a publicly traded diversified energy company headquartered in Newark, New Jersey. The company’s largest subsidiary retains the old PSE&G name. New Jersey’s oldest and largest investor owned utility, Public Service Electric and Gas Company is a regulated gas and electric utility company serving the state of New Jersey.[3]

The Public Service Corporation was formed in 1903 by amalgamating more than 400 gas, electric and transportation companies in New Jersey. It was renamed Public Service Electric and Gas Company in 1948. The transportation operations of PSE&G were purchased by New Jersey Transit in 1980, leaving PSE&G exclusively in the utility business. In 1985, Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG) formed as a holding company, and in 1989 established Enterprise Diversified Holdings Inc. (now PSEG Energy Holdings), to begin consolidation of its unregulated businesses. In 2000, PSE&G split its unregulated national power generation assets to form PSEG Power, while PSE&G continued operating in New Jersey as a regulated gas and electric delivery company.[4]

In June 2005, the acquisition of PSEG by Exelon, a Chicago and Philadelphia based utility conglomerate, was approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission; however, the deal was never consummated and eventually dissolved after it became clear that it would not win state regulatory approval from the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities.[5]

In 2009, PSEG began installing solar panels on 200,000 utility poles in its service area in a project costing $773 million, the largest such project in the world.[6][7] The Solar 4 All project increased the capacity for renewable energy in New Jersey and was completed in 2013.[8] In addition, PSEG is building four solar farms in Edison, Hamilton, Linden, and Trenton.[9]

Public Service Enterprise Group consists of four companies:

- Public Service Electric and Gas (PSE&G)

- PSEG Long Island, LLC

- PSEG Power

- PSEG Fossil

- PSEG Nuclear

- PSEG Energy Resources and Trade

- PSEG Energy Holdings

- PSEG Global

- PSEG Solar Source, LLC

- PSEG Resources

- PSEG Services Corporation[13]

Kearny plant

PSE&G serves the population in an area consisting of a 2,600-square-mile (6,700 km2) diagonal corridor across the state from Bergen to Gloucester Counties.[14][15] PSE&G is the largest provider of gas and electric service, servicing 1.8 million gas customers and 2.2 million electric customers in more than 300 urban, suburban and rural communities, including New Jersey’s six largest cities.

PSEG Nuclear operates three nuclear reactors at two facilities in Lower Alloways Creek Township. PSEG owns one reactor at Hope Creek Nuclear Generating Station and operates two reactors at Salem Nuclear Power Plant where PSEG Nuclear holds a 57 percent stake (in partnership with Exelon Corporation). Exelon also operates two reactors at Peach Bottom Nuclear Generating Station in a 50/50 joint venture with PSEG.[16]

PSEG Long Island provides electricity to 1.1 million customers in Nassau and Suffolk counties, and the Rockaway Peninsula of Queens, part of New York City.[17] This system operates under an agreement with the Long Island Power Authority, the state agency that owns the system, that went into effect January 1, 2014.[18] PSEG was selected to essentially privatize LIPA, taking over near complete control of the system including its brand name, whereas before this agreement only a number of functions were performed by the private sector and the system was operated under the LIPA name.

System information

PSEG’s transmission line voltages are 500,000 volts, 345,000 volts, 230,000 volts and 138,000 volts with interconnections to utilities in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New York. The company’s subtransmission voltages are 69,000 volts and 26,000 volts. PSEG’s distribution voltages are 13,000 volts and 4,160 volts.

Environmental record

In 2001, PSEG received The Walter B. Jones Memorial and NOAA Excellence Awards in Coastal and Ocean Resource Management[19] in the category of Excellence in Business Leadership for its Estuary Enhancement Program.[20]

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have identified PSEG as the 48th-largest corporate producer of air pollution in the United States, with roughly five million pounds of toxic chemicals released annually into the air.[21] Major pollutants indicated by the study include manganese, chromium and nickel salts; sulfuric and hydrochloric acid.[22]

For more information please visit the following link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_Service_Enterprise_Group

Leave a Reply