Trip To Swansea In My Husband’s Motherland , Wales –Part 9

John Watts’ Artwork and Welsh history

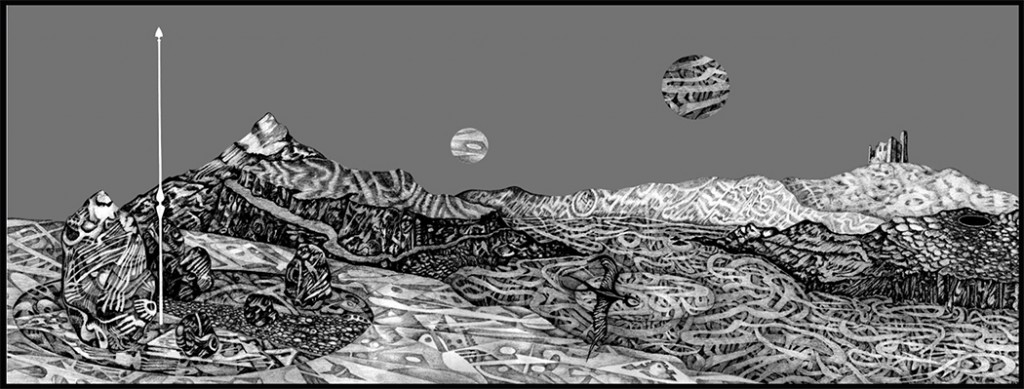

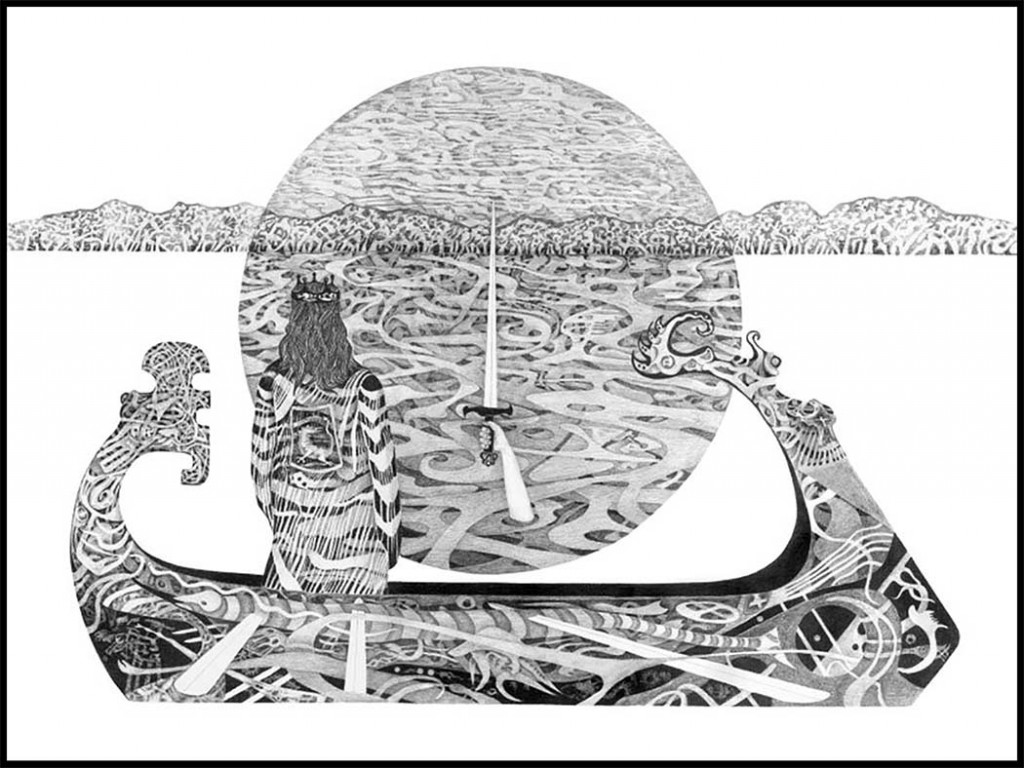

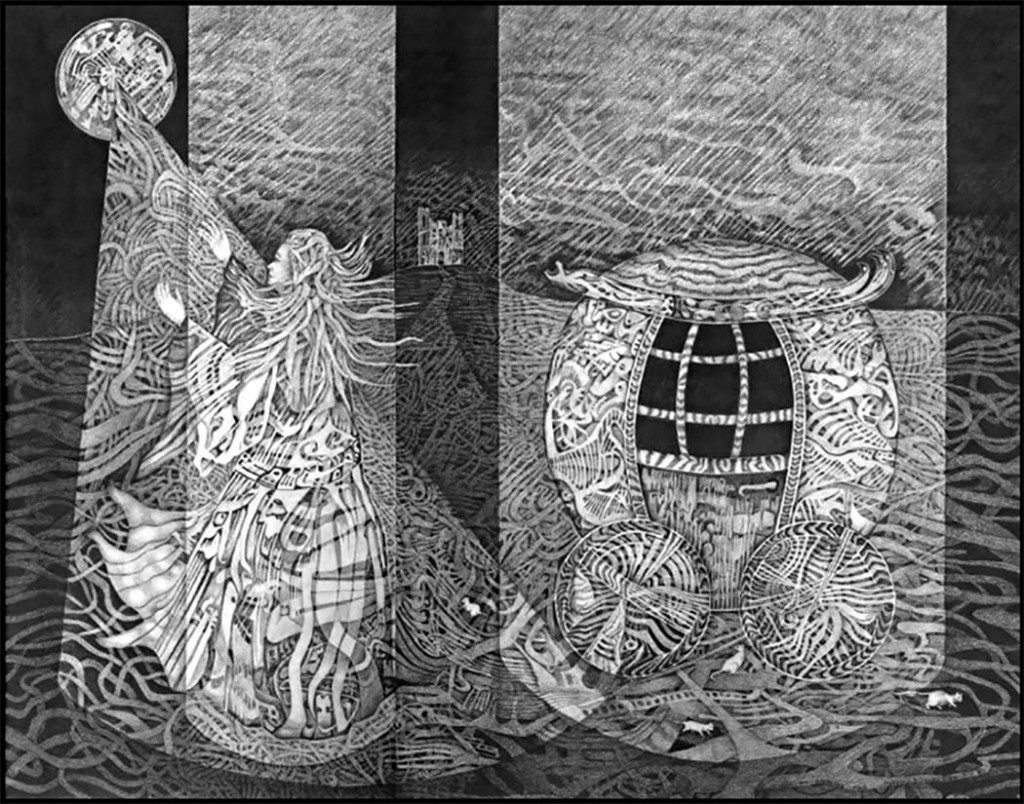

Swansea Landscape: Artwork by John Watts, Welsh Artist

Swansea Landscape: Artwork by John Watts, Welsh Artist

Oystermouth Castle (Welsh: Castell Ystum Llwynarth) is a Norman stone castle in Wales, overlooking Swansea Bay on the east side of the Gower Peninsula near the village of the Mumbles.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oystermouth_Castle

Oystermouth castle, with its village and lighthouse, 1839

Newman and Co. (London, England), engraver. – This image is available from the National Library of Wales You can view this image in its original context on the NLW Catalogue

Abstract: A view of the ruins of Oystermouth castle with ships in the bay below and a lighthouse in the background.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oystermouth_Castle

Oystermouth Castle, showing the gatehouse and the chapel window

Oystermouth Castle, showing the gatehouse and the chapel window

The first castle was founded by William de Londres of Ogmore Castle soon after 1106 following the capture of Gower by the Normans. In 1116 the Welsh of Deheubarth retook the Gower Peninsula and forced William to flee his castle which was put to the torch. The castle was rebuilt soon afterwards, but was probably destroyed again in 1137 when Gower was once more retaken by the princes of Deheubarth. The Londres or London family finally died out in 1215 when Gower was again taken by the Welsh under the leadership of Llywelyn the Great. In 1220 the Welsh were expelled from the peninsula and the government of Henry III of England returned the barony of Gower to John de Braose who rebuilt both Swansea Castle and Oystermouth. For more information please visit the following link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oystermouth_Castle

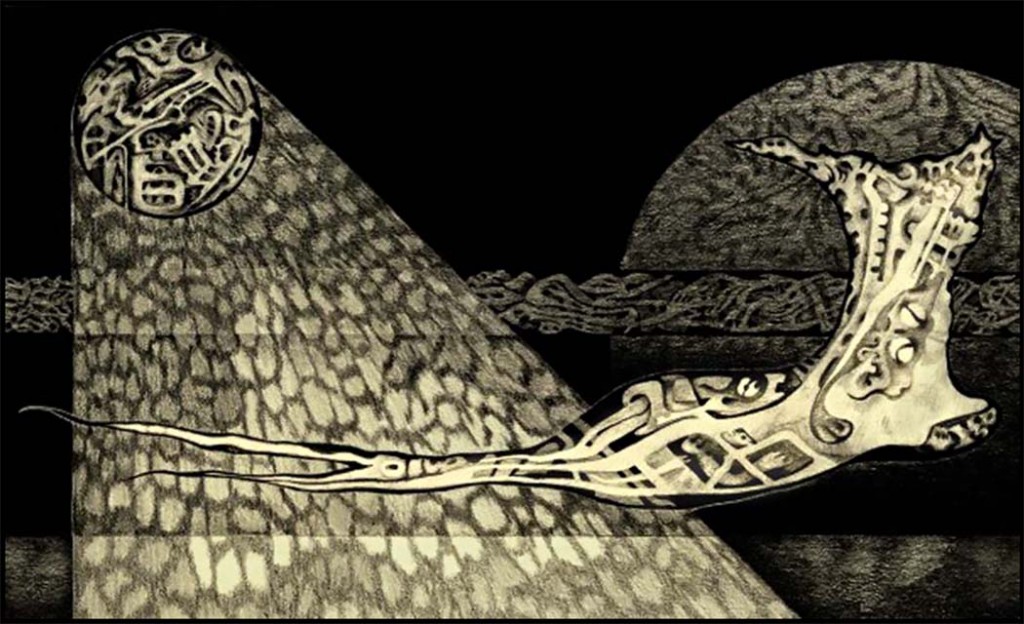

Cross and Creature 2: Artwork by John Watts

Cross and Creature 2: Artwork by John Watts

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic languages.

Celtic art is a difficult term to define, covering a huge expanse of time, geography and cultures. A case has been made for artistic continuity in Europe from the Bronze Age, and indeed the preceding Neolithic age; however archaeologists generally use “Celtic” to refer to the culture of the European Iron Age from around 1000 BC onwards, until the conquest by the Roman Empire of most of the territory concerned, and art historians typically begin to talk about “Celtic art” only from the La Tène period (broadly 5th to 1st centuries BC) onwards.[1] Early Celtic art is another term used for this period, stretching in Britain to about 150 AD.[2] The Early Medieval art of Britain and Ireland, which produced the Book of Kells and other masterpieces, and is what “Celtic art” evokes for much of the general public in the English-speaking world, is called Insular art in art history. This is the best-known part, but not the whole of, the Celtic art of the Early Middle Ages, which also includes the Pictish art of Scotland.[3]

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celtic_art

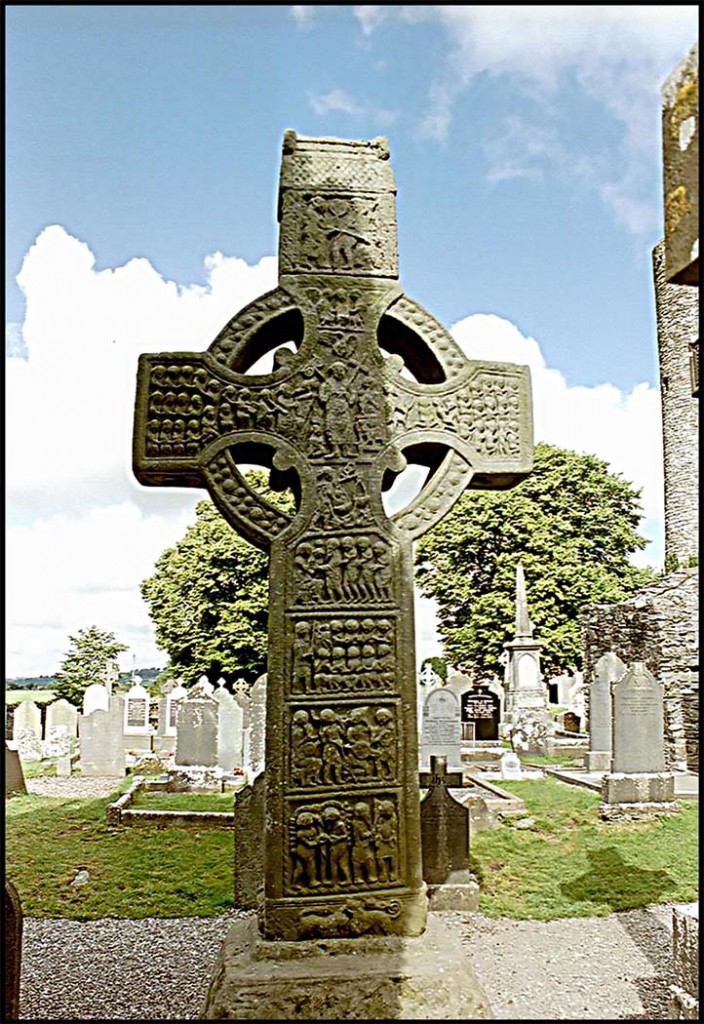

Muiredach’s High Cross, Ireland, early 10th century

High cross. A tall stone standing cross, usually of Celtic cross form. Decoration is abstract often with figures in carved relief, especially crucifixions, but in some cases complex multi-scene schemes. Most common in Ireland, but also in Great Britain and near continental mission centres.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celtic_art

The Ancient Art of the Celtic People

From The Daily Beast, written by William O’Connor

“Boston Celtics, Celtic pride, Celtic crosses, Celtic tattoos. St. Patrick’s Day is far from the only time we remind ourselves that being Irish has something to do with the Celts. Today, the word Celtic conjures up the aforementioned items and perhaps some vague notions of Druids and art featuring complicated, interwoven lines. In reality, the Celtic history is far older, richer, and more significant than most realize. A new book from Phaidon, Celtic Art, by Venceslas Kruta, takes a deep dive into the impressive artistic history of a people who, as the books notes, in Greek and Roman times “were the largest known family of European peoples outside the Mediterranean.” At its peak, the people who spoke Celtic languages and practiced Celtic culture stretched from the Atlantic to Asia Minor. While that is impressive, what is more impressive is the artwork left behind—the impossibly detailed jewelry, weaponry, and decorative items that show an extraordinary mastery of craft.

To the left is the famous illuminated “Chi-Rho” page of the Book of Kells from about 700–900. While Celtic religion forbade the writing down of pretty much anything, Christianity’s spread ensured that traditional Celtic imagery survived in stunning manuscripts.

Richly illuminated manuscript on parchment, dimensions: 33 x 25 cm, Dublin, Trinity College Library.”

For more information please visit the following link:

https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-ancient-art-of-the-celtic-people-photos?ref=scroll

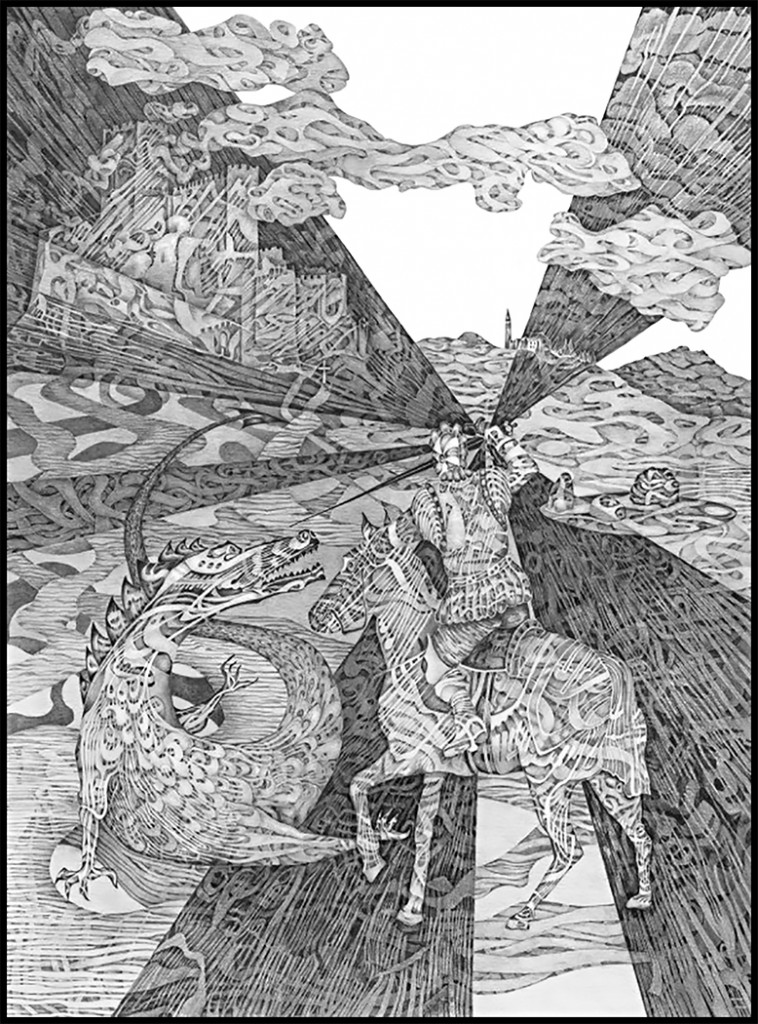

Birth of Dragon: Artwork by John Watts

The Welsh Dragon (Welsh: Y Ddraig Goch, meaning the red dragon, pronounced [? ?ðrai? ??o??]) appears on the national flag of Wales. The oldest recorded use of the dragon to symbolise Wales is in the Historia Brittonum, written around AD 829, but it is popularly supposed to have been the battle standard of King Arthur and other ancient Celtic leaders. Its association with these leaders along with other evidence from archaeology, literature, and documentary history led many to suppose that it evolved from an earlier Romano-British national symbol.[1] During the reigns of the Tudor monarchs, the red dragon was used as a supporter in the English Crown’s coat of arms (one of two supporters, along with the traditional English lion).[2] The red dragon is often seen as symbolising all things Welsh, and is used by many public and private institutions. These include the Welsh Government, Visit Wales, the dragon’s tongue is in use with the Welsh Language Society and numerous local authorities including Blaenau Gwent, Cardiff, Carmarthenshire, Rhondda Cynon Taf, Swansea, and sports bodies, including the Sport Wales National Centre, the Football Association of Wales, Wrexham A.F.C., Newport Gwent Dragons, and London Welsh RFC.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_Dragon

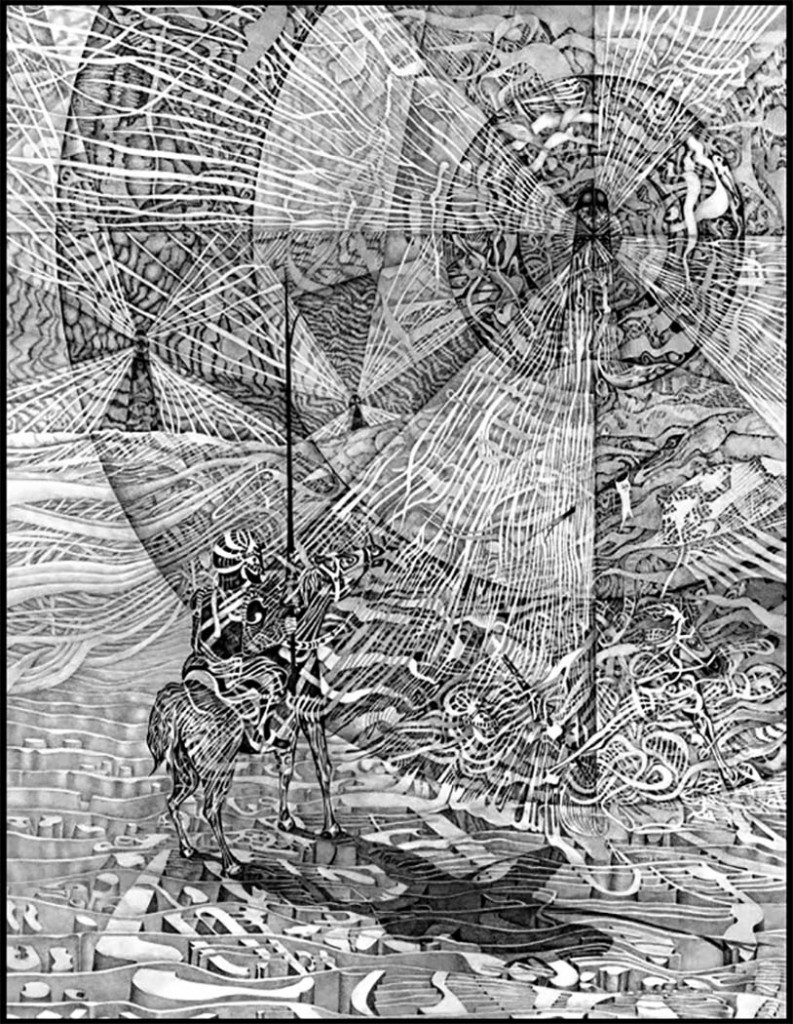

King Arthur: Artwork by John Watts

The Arthurian Legend

Geoffrey of Monmouth is known as the Father of the Arthurian Legend for developing the character of King Arthur, adding mythical elements to his story, and introducing many of the central characters and motifs which would later be expanded upon by other writers.

The phrase Arthurian Legend encompasses a number of different versions of the tale but, in the present day, mainly refers to the English work of Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte D’Arthur (Death of Arthur) published by William Caxton in 1485 CE. The legend developed from History of The Kings of Britain, passing over to France, to Germany, to Spain and Portugal, and back to England with numerous additions and versions proliferating, until Malory compiled, edited, revised, and rewrote a prose version in 1469 CE while he was in prison

For more information please visit the following link:

https://www.ancient.eu/King_Arthur/

Ing & John’s Art Exhibition, June 2013 at 194 Market Street, Second floor, Newark, New Jersey

For more information please visit the following link:

https://ingpeaceproject.com/ing-johns-art-exhibition-6-2013/

King Arthur & the Lady of the Lake

The basic story goes that, once upon a time, there was a wizard named Merlin who arranged for a mighty king named Uther Pendragon to sleep with a queen named Igrayne who was another king’s wife. Merlin’s stipulation was that, when the child of their union was born, it would be given to him. All of this happens as it should, the child is named Arthur, and he is given to another lord, Sir Hector, to raise with his own son Kay. Many years later, when Arthur is grown, he accompanies Kay and Hector to a tournament in which Kay is to compete, finds that he forgot Kay’s sword at home, and so takes one he finds in the forest stuck in a stone. This is the Sword in the Stone which can only be drawn from the rock by the true king of Britain.

Merlin returns at this point to explain the situation to Arthur, who had no idea he was adopted, and helps him fight the other lords who contest his claim to the throne. Although the Sword in the Stone is frequently associated with the famous weapon Excalibur, they are two different swords. The sword Arthur draws from the stone is broken in a fight with Sir Pellinore and Merlin brings Arthur to a mystical body of water where the Lady of the Lake gives him Excalibur.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://www.ancient.eu/King_Arthur/

Knights of the Round Table

In the enchanted lands of the Arthurian realm aNything can happen, at any time, but goodness will always triumph over evil & darkness can never put out the light.

Excalibur is more than just a sword; it is a symbol of Arthur’s greatness. In some versions of the legend Arthur gives the sword to Sir Gawain but, in most, it is exclusively Arthur’s. This is in keeping with many ancient tales and legends in which a great hero has some kind of magical weapon. Once Arthur has forced the other lords to recognize his legitimacy, he marries the beautiful queen Guinevere and sets up his court at Camelot.

He invites the greatest knights of the realm to come and dine in his banquet hall but, when they do, they begin fighting over who will get the best seat. Arthur severely punishes the knight who began the trouble and, to avert any repeat in the future, accepts a round table from his father-in-law. From this time on, he explains, everyone sitting at the table will be equal, including himself, and everyone’s opinions will be weighed seriously no matter their social standing. Further, anyone requiring assistance will be welcomed in the hall to request it and every wrong shall be righted by Arthur and his knights.

The motif of the Round Table, along with the magical weapon, sets Arthur above the kings who have preceded him who believed that their position of power dictated what was right or wrong; Arthur believes that everyone’s opinion is valid and that might should be used to support right, not define it. Arthur again sends out invitations to noble knights to join him but this time his messengers are to go even farther, beyond the boundaries of Britain.

Knights of the Round Table

Among the knights who answer his call is Lancelot of the Lake, a French knight who is unrivaled in combat. He and Arthur become friends at the same time that he falls in love with Guinevere and she with him. While this affair is going on behind the scenes, the Knights of the Round Table are engaging in all kinds of fantastic adventures. If there is no apparent adventure, Arthur will go off and find one. In the famous story of Gawain and the Green Knight, a challenger comes to court to start the adventure. In the story of Jaufre (also known as Girflet) he arrives at the court to be knighted and then proceeds on his own adventures before returning and involving the others.

The greatest adventure the knights undertake is the quest for the Holy Grail. The grail is originally a platter in the French version of the legend or cauldron in the Welsh. It is transformed, however, into the cup of Christ used at the Last Supper by the time Malory revises the story and this is how it is generally understood. The grail quest can only be completed by a knight pure of heart and this is finally accomplished by Galahad, son of Lancelot.

Arthur remains a good & noble king until the affair of his queen & best friend is revealed by his son Mordred.

Throughout all these adventures there are a number of times Guinevere is kidnapped by some menacing lord and has to be rescued or other ladies are in distress and also need the assistance of a noble knight. There are dragons, giants, invisible spirits, sacred wells, unending waters to cross, inanimate objects which move and speak, courageous heroes, scheming villains, women who are beautiful and noble and others whose beauty conceals their devious nature. Encountering all of these, Arthur remains a good and noble king until the affair of his queen and best friend is revealed by Arthur’s illegitimate son Mordred who then challenges Arthur’s right to rule.

In the final battle between Mordred and Arthur, Mordred is killed and Arthur mortally wounded. Guinevere retires to a convent and Lancelot to a hermitage. All of the other great knights of the court are killed. Sir Bedevere helps Arthur from the field and returns Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake. Once the sword has been returned, Arthur dies and is carried away on a ship to the isle of Avalon.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://www.ancient.eu/King_Arthur/

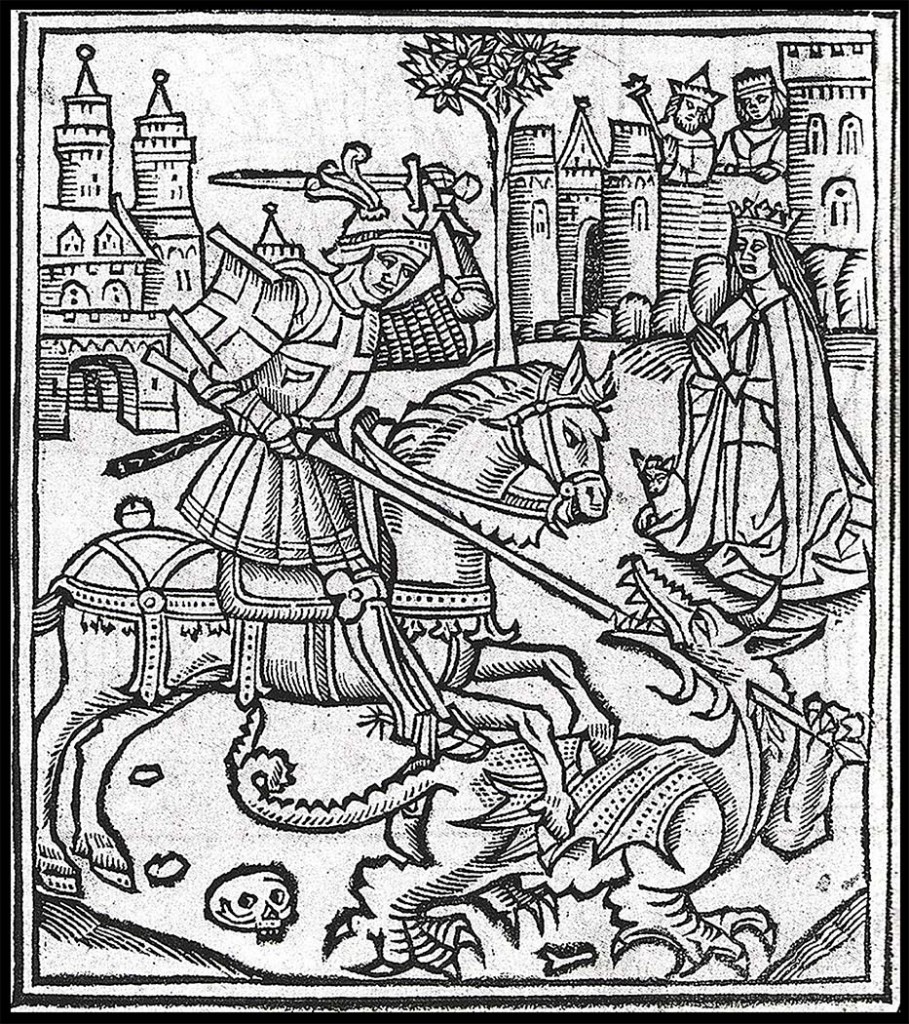

St. George & Dragon: Artwork by John Watts, Welsh Artist

John Watts, my husband said that “I support the dragon”

Ing & John’s Art Exhibition, June 2013 at 194 Market Street, Second floor, Newark, New Jersey

For more information please visit the following link:

https://ingpeaceproject.com/ing-johns-art-exhibition-6-2013/

Woodcut frontispiece of Alexander Barclay, Lyfe of Seynt George (Westminster, 1515).

Alexander Barclay (1476-1552) – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:St_GeorgeEnglish.JPG

Life of Saint George, Woodcut of St George Slaying the Dragon, 1515, by Alexander Barclay (1476-1552)

The Saint George and the Dragon legend describes the saint taming and slaying a dragon that demanded human sacrifices; the saint thereby rescues the princess chosen as the next offering.

Only a kernel of the legend occurs in the ancient hagiography of Saint George dating to the 7th century or earlier. Here, a monarch referred to as “dragon of the abyss” persecutes the saint. The dragon-slaying may have been transferred from the legend attached to St. Theodore.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_George_and_the_Dragon

Miniature from a Passio Sancti Georgii manuscript (Verona, second half of 13th century)

Saint George and the Dragon in medieval miniature.

The motif of Saint George as a knight on horseback slaying the dragon first appears in western art in the second half of the 13th century. The tradition of the saint’s arms being shown as the red-on-white St. George’s Cross develops in the 14th century.

The Saint George and the Dragon legend describes the saint taming and slaying a dragon that demanded human sacrifices; the saint thereby rescues the princess chosen as the next offering.

Only a kernel of the legend occurs in the ancient hagiography of Saint George dating to the 7th century or earlier. Here, a monarch referred to as “dragon of the abyss” persecutes the saint. The dragon-slaying may have been transferred from the legend attached to St. Theodore.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_George_and_the_Dragon

Vortigern and Ambros watch the fight between the red and white dragons: an illustration from a 15th-century manuscript of Geoffrey of Monmouth‘s

Welsh Dragon: Mabinogion

In the Mabinogion story Lludd and Llefelys, the red dragon fights with an invading White Dragon. His pained shrieks cause women to miscarry, animals to perish and plants to become barren. Lludd, king of Britain, goes to his wise brother Llefelys in France. Llefelys tells him to dig a pit in the centre of Britain, fill it with mead, and cover it with cloth. Lludd does this, and the dragons drink the mead and fall asleep. Lludd imprisons them, still wrapped in their cloth, in Dinas Emrys in Snowdonia (Welsh: Eryri).

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_Dragon

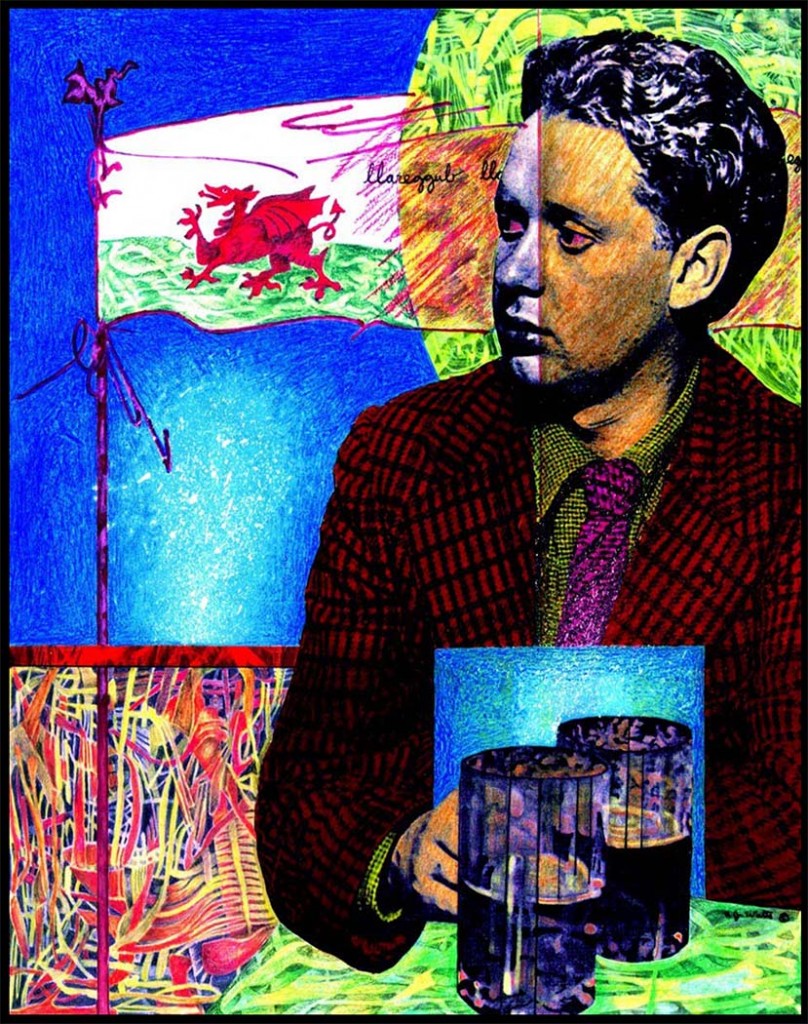

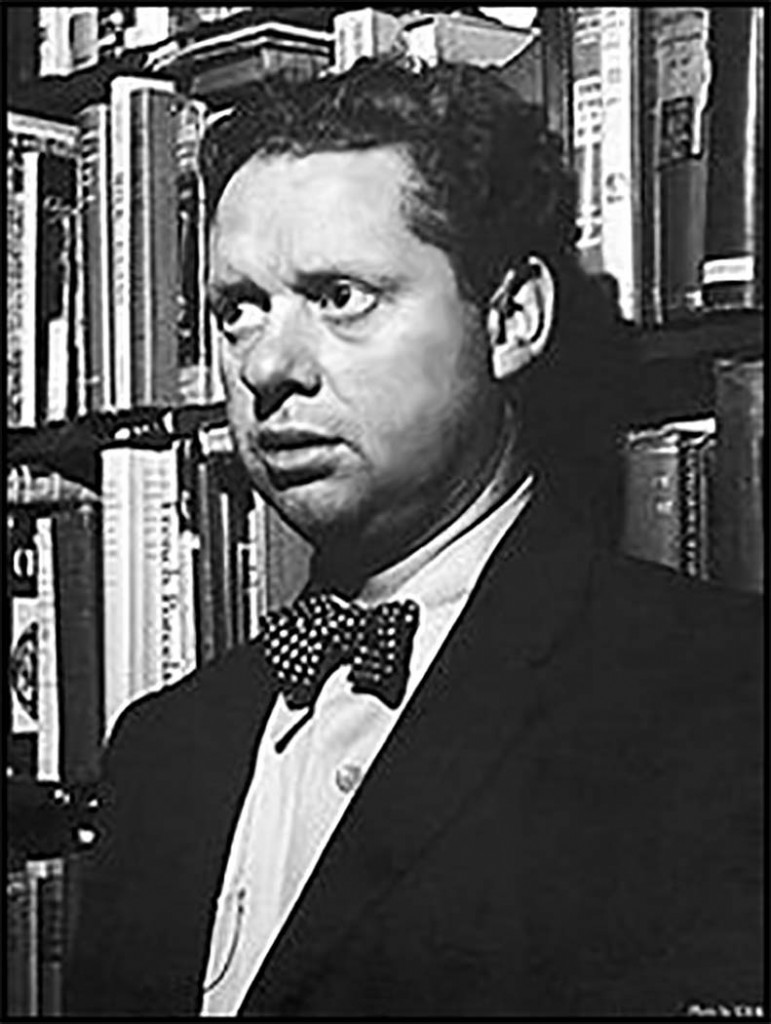

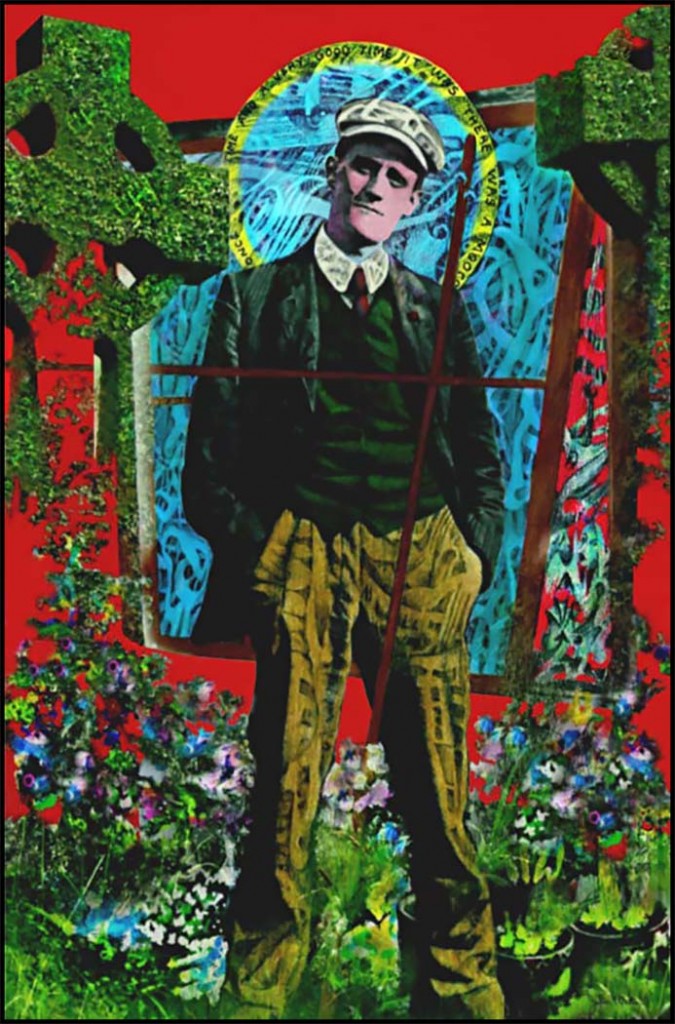

Dylan Thomas: Artwork by John Watts, Welsh Artist

Poem by Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night

Dylan Thomas, 1914 – 1953

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/do-not-go-gentle-good-night

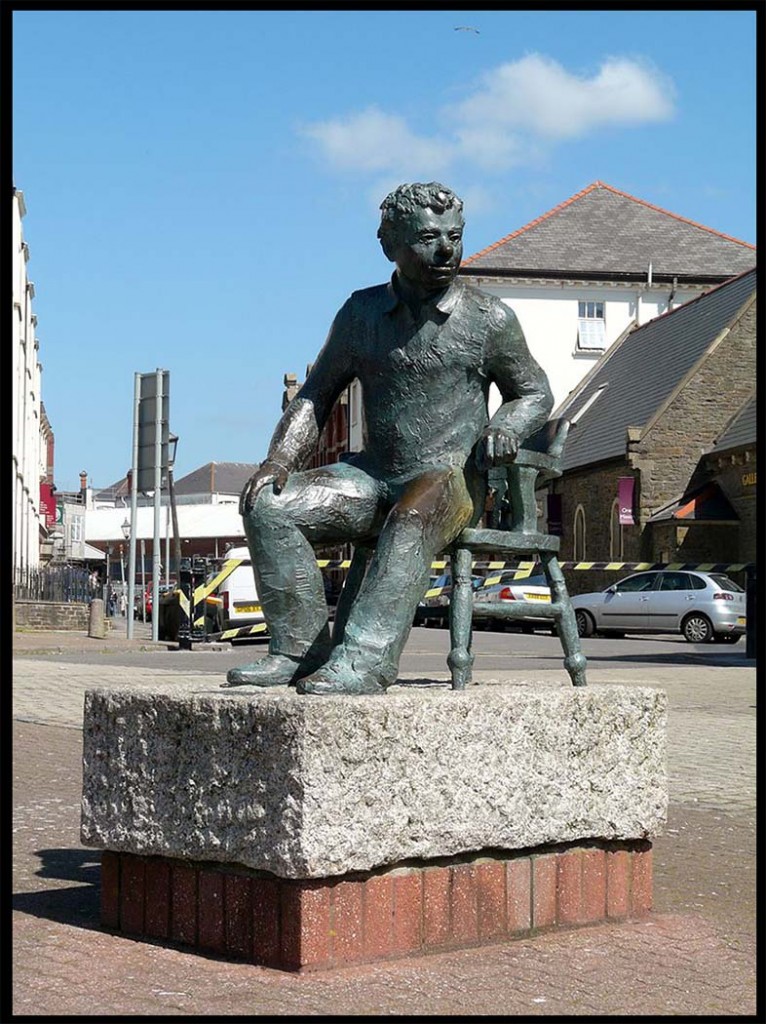

Memorial:Statue of Thomas in Swansea, Wales, UK

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems “Do not go gentle into that good night” and “And death shall have no dominion“; the ‘play for voices’ Under Milk Wood; and stories and radio broadcasts such as A Child’s Christmas in Wales and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog. He became widely popular in his lifetime and remained so after his premature death at the age of 39 in New York City. By then he had acquired a reputation, which he had encouraged, as a “roistering, drunken and doomed poet”.[3]

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dylan_Thomas

Thomas was born in Swansea, Wales, in 1914. An undistinguished pupil, he left school at 16 and became a journalist for a short time. Many of his works appeared in print while he was still a teenager; however, it was the publication in 1934 of “Light breaks where no sun shines” that caught the attention of the literary world. While living in London, Thomas met Caitlin Macnamara, whom he married in 1937. Their relationship was defined by alcoholism and was mutually destructive.[3] In the early part of their marriage, Thomas and his family lived hand-to-mouth; they settled in the Welsh fishing village of Laugharne.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dylan_Thomas

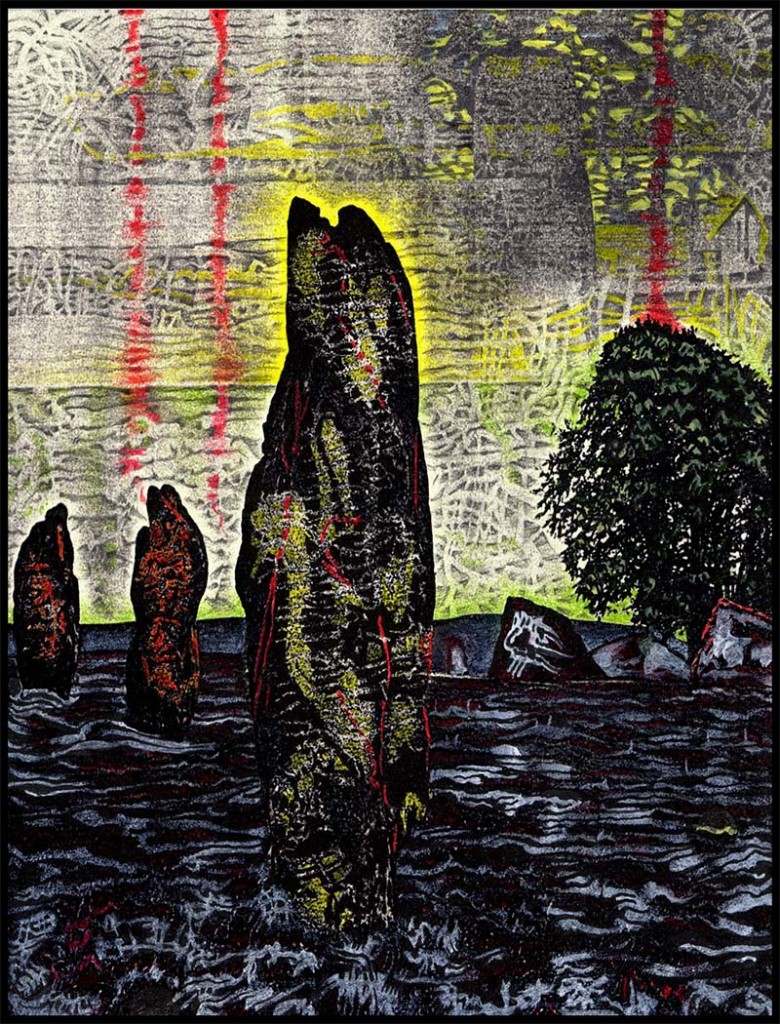

Stone Clouds: Artwork by John Watts

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument in Wiltshire, England, 2 miles (3 km) west of Amesbury. It consists of a ring of standing stones, with each standing stone around 13 feet (4.0 m) high, 7 feet (2.1 m) wide and weighing around 25 tons. The stones are set within earthworks in the middle of the most dense complex of Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments in England, including several hundred burial mounds.[1]

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonehenge

Stonehenge in 2007

Stonehenge: garethwiscombe – https://www.flickr.com/photos/garethwiscombe/1071477228/in/photostream/

CC BY 2.0, File:Stonehenge2007 07 30.jpg, Created: 30 July 2007

Archaeologists believe it was constructed from 3000 BC to 2000 BC. The surrounding circular earth bank and ditch, which constitute the earliest phase of the monument, have been dated to about 3100 BC. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the first bluestones were raised between 2400 and 2200 BC,[2] although they may have been at the site as early as 3000 BC.[3][4][5]

One of the most famous landmarks in the UK, Stonehenge is regarded as a British cultural icon.[6] It has been a legally protected Scheduled Ancient Monument since 1882 when legislation to protect historic monuments was first successfully introduced in Britain. The site and its surroundings were added to UNESCO‘s list of World Heritage Sites in 1986. Stonehenge is owned by the Crown and managed by English Heritage; the surrounding land is owned by the National Trust.[7][8]

Stonehenge could have been a burial ground from its earliest beginnings.[9] Deposits containing human bone date from as early as 3000 BC, when the ditch and bank were first dug, and continued for at least another five hundred years.[10]

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonehenge

The Sun rising over Stonehenge on the morning of the Summer Solstice (21st June 2005).

The Sun rising over Stonehenge on the morning of the Summer Solstice (21st June 2005).

Photograph by Andrew Dunn, 21 June 2005.

A crowd of between 14,000 and 19,000 people watched the sunrise from the ground, along with three paramotor pilots who watched the events from the air.

This photograph was taken a couple of minutes after sunrise, and a little to the right of the solar alignment line. A more perfectly aligned photograph taken immediately after sunrise can be seen at Image:Summer Solstice 2005 Sunrise over Stonehenge 01.jpg.

Description of the solar alignment

If you look at an aerial view, north is approximately along the path to the right. On the morning of the solstice, the sun rises from behind the Heel Stone in the bottom right hand corner, and can be observed on an alignment running from the Heel stone, passing between the two Slaughter Stones (only one remains fallen on the outer bank), through the outer Sarsen ring, across the centre of the henge, then between the tallest trilith at the back of the Sarsen horseshoe. If you continue the line onward to the bank and ditch top left, that’s the point from which this photo is taken.

Tallest stone

Today the tallest trilith at the back of the Sarsen horseshoe is largely collapsed. Only one of its three stones remains standing, which is the tallest stone just left of the sun in this photograph.

The lintel stones on the triliths and the outer Sarsen circle are held in place with mortise and tenon joints. I believe the triangular spike on top of the tallest stone, is the tenon exposed after its neighbouring stones had fallen.

Photograph Andrew Dunn, 21 June 2005.

Website: htt://www.andrewdunphoto.com/

For more information please visit the following link:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Summer_Solstice_Sunrise_over_Stonehenge_2005.jpg

Stones 2: Artwork by John Watts, Welsh Artist

“Heel Stone”, “Friar’s Heel”, or “Sun-Stone”

The Heel Stone lies north east of the sarsen circle, beside the end portion of Stonehenge Avenue.[41] It is a rough stone, 16 feet (4.9 m) above ground, leaning inwards towards the stone circle.[41] It has been known by many names in the past, including “Friar’s Heel” and “Sun-stone”.[42][43] At summer solstice an observer standing within the stone circle, looking north-east through the entrance, would see the Sun rise in the approximate direction of the heel stone, and the sun has often been photographed over it.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonehenge

“Heel Stone”, “Friar’s Heel”, or “Sun-Stone”

A folk tale relates the origin of the Friar’s Heel reference.[44][45]

The Devil bought the stones from a woman in Ireland, wrapped them up, and brought them to Salisbury plain. One of the stones fell into the Avon, the rest were carried to the plain. The Devil then cried out, “No-one will ever find out how these stones came here!” A friar replied, “That’s what you think!”, whereupon the Devil threw one of the stones at him and struck him on the heel. The stone stuck in the ground and is still there.[46] Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable attributes this tale to Geoffrey of Monmouth, but though book eight of Geoffrey’s Historia Regum Britanniae does describe how Stonehenge was built, the two stories are entirely different.

The name is not unique; there was a monolith with the same name recorded in the nineteenth century by antiquarian Charles Warne at Long Bredy in Dorset.[47]

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonehenge

Dancing inside the stones, 1984 Stonehenge Free Festival

Dancing inside the stones, 1984 Stonehenge Free Festival

Salix alba at en.wikipedia Photo of the en:Stonehenge Free Festival in 1984

CC BY-SA 3.0, File:Stonehenge84.jpg, Created: 31 December 1983

The earlier rituals were augmented by the Stonehenge Free Festival, loosely organised by the Politantric Circle, held between 1972 and 1984, during which time the number of midsummer visitors had risen to around 30,000.[67] However, in 1985 the site was closed to festivalgoers by English Heritage and the National Trust. A consequence of the end of the festival in 1985 was the violent confrontation between the police and New Age travellers that became known as the Battle of the Beanfield when police blockaded a convoy of travellers to prevent them from approaching Stonehenge. Beginning in 1985, the year of the Battle of the Beanfield, no access was allowed into the stones at Stonehenge for any religious reason. This ‘exclusion zone’ policy continued for almost fifteen years and until just before the arrival of the twenty-first century, visitors were not allowed to go into the stones at times of religious significance: the two Solstices (Winter and Summer) and two Equinoxes (Vernal and Autumnal).[68]

However, now due to the Roundtable process and the ‘Court of Human Rights’ rulings gained by picketing by campaigners such as Brian “Viziondanz” Felstein and King Arthur Pendragon, some access had been gained four times a year. The ‘Court of Human Rights’ rulings recognises that members of any genuine religion have a right to worship in their own church, and Stonehenge is a place of worship to Neo-Druids, Pagans and other ‘Earth based’ or ‘old’ religions. The Roundtable meetings include members of the Wiltshire Police force, National Trust, English Heritage, Pagans, Druids, Spiritualists and others.

At the Summer Solstice 2003, which fell over a weekend, over 30,000 people attended a gathering at and in the stones. The 2004 gathering was smaller (around 21,000 people).

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonehenge

Stones twice: Artwork by John Watts, Welsh Artist

On 18 December 2011, geologists from University of Leicester and the National Museum of Wales announced the discovery of the exact source of some of the rhyolite fragments found in the Stonehenge debitage. These fragments do not seem to match any of the standing stones or bluestone stumps. The researchers have identified the source as a 70-metre (230 ft) long rock outcrop called Craig Rhos-y-Felin (51°59?30.07?N 4°44?40.85?W), near Pont Saeson in north Pembrokeshire, located 220 kilometres (140 mi) from Stonehenge.[85][86]

On 10 September 2014 the University of Birmingham announced findings including evidence of adjacent stone and wooden structures and burial mounds, overlooked previously, that may date as far back as 4000 BC.[17] An area extending to 12 square kilometres (1,200 ha) was studied to a depth of three metres with ground-penetrating radar equipment. As many as seventeen new monuments, revealed nearby, may be Late Neolithic monuments that resemble Stonehenge. The interpretation suggests a complex of numerous related monuments. Also included in the discovery is that the cursus track is terminated by two five-meter wide extremely deep pits,[87] whose purpose is still a mystery.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonehenge

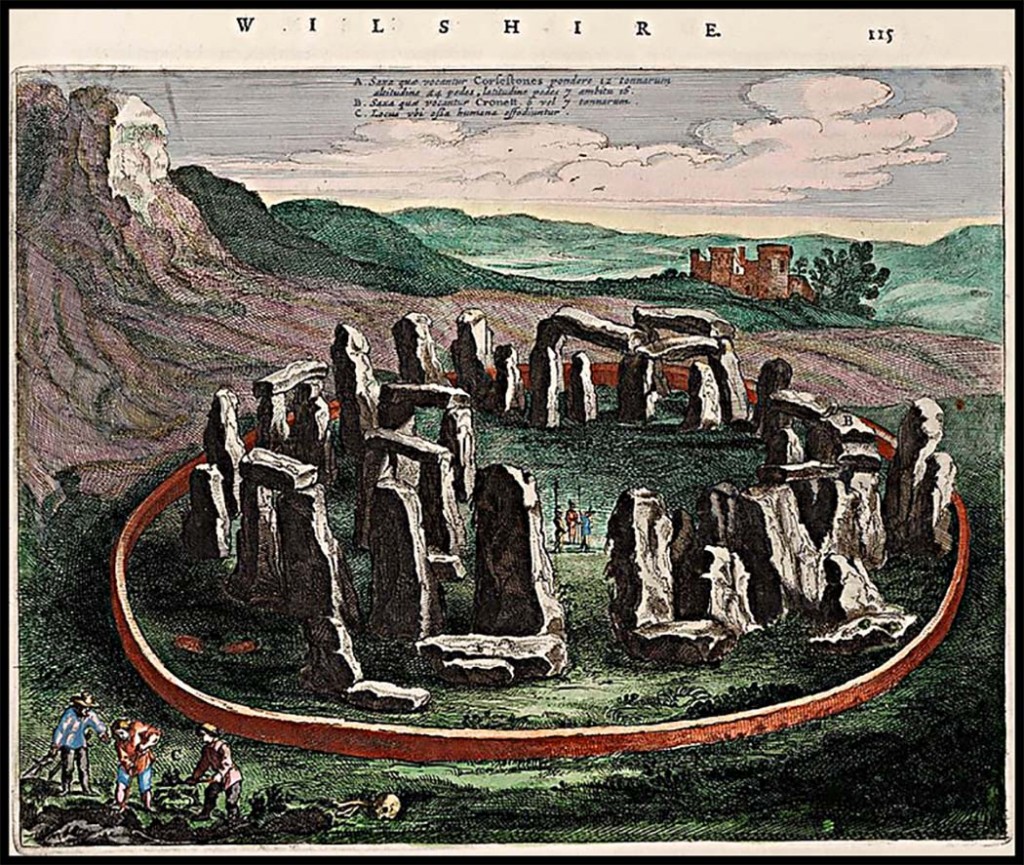

Seventeenth century depiction of Stonehenge from the Atlas van Loon

Seventeenth century depiction of Stonehenge from the Atlas van Loon

1600–1900

Throughout recorded history, Stonehenge and its surrounding monuments have attracted attention from antiquarians and archaeologists. John Aubrey was one of the first to examine the site with a scientific eye in 1666, and recorded in his plan of the monument the pits that now bear his name. William Stukeley continued Aubrey’s work in the early eighteenth century, but took an interest in the surrounding monuments as well, identifying (somewhat incorrectly) the Cursus and the Avenue. He also began the excavation of many of the barrows in the area, and it was his interpretation of the landscape that associated it with the Druids.[69] Stukeley was so fascinated with Druids that he originally named Disc Barrows as Druids’ Barrows. The most accurate early plan of Stonehenge was that made by Bath architect John Wood in 1740.[70] His original annotated survey has recently been computer redrawn and published.[71][page?needed] Importantly Wood’s plan was made before the collapse of the southwest trilithon, which fell in 1797 and was restored in 1958.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonehenge

An early photograph of Stonehenge taken July 1877

William Cunnington was the next to tackle the area in the early nineteenth century. He excavated some 24 barrows before digging in and around the stones and discovered charred wood, animal bones, pottery and urns. He also identified the hole in which the Slaughter Stone once stood. Richard Colt Hoare supported Cunnington’s work and excavated some 379 barrows on Salisbury Plain including on some 200 in the area around the Stones, some excavated in conjunction with William Coxe. To alert future diggers to their work they were careful to leave initialled metal tokens in each barrow they opened. Cunnington’s finds are displayed at the Wiltshire Museum. In 1877 Charles Darwin dabbled in archaeology at the stones, experimenting with the rate at which remains sink into the earth for his book The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stonehenge

The following are more of John Watts’artworks:

Prey small: Artwork by John Watts

Prey small: Artwork by John Watts

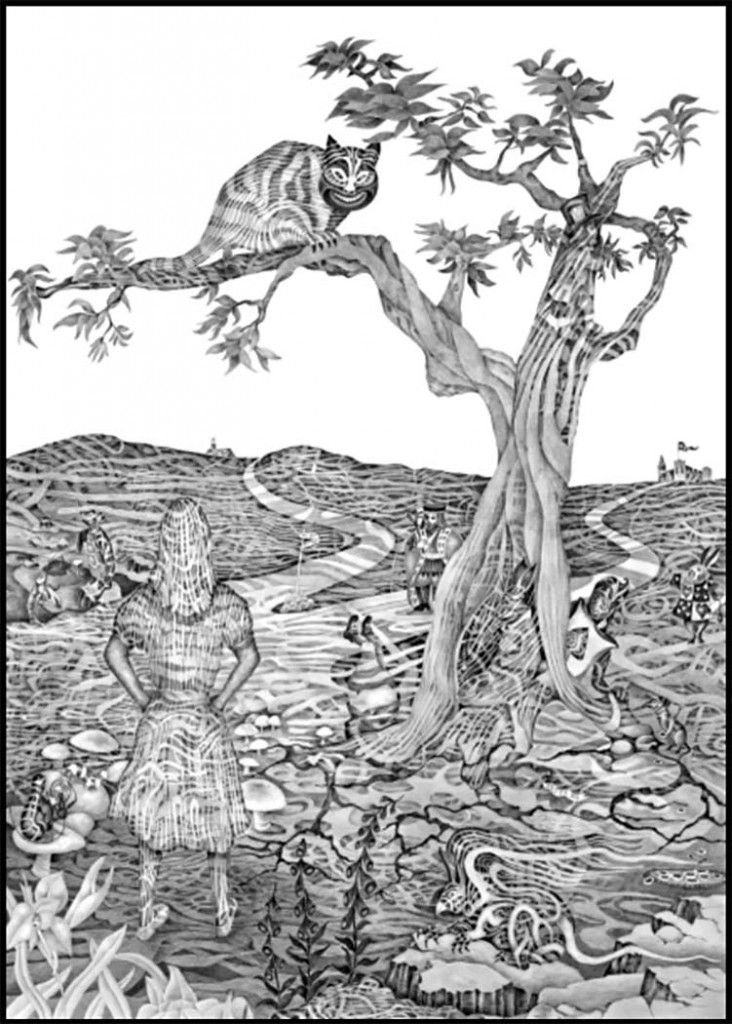

Alice Final: Artwork by John Watts

Alice Final: Artwork by John Watts

Ameba: Artwork by John Watts

Cinderella: Artwork by John Watts

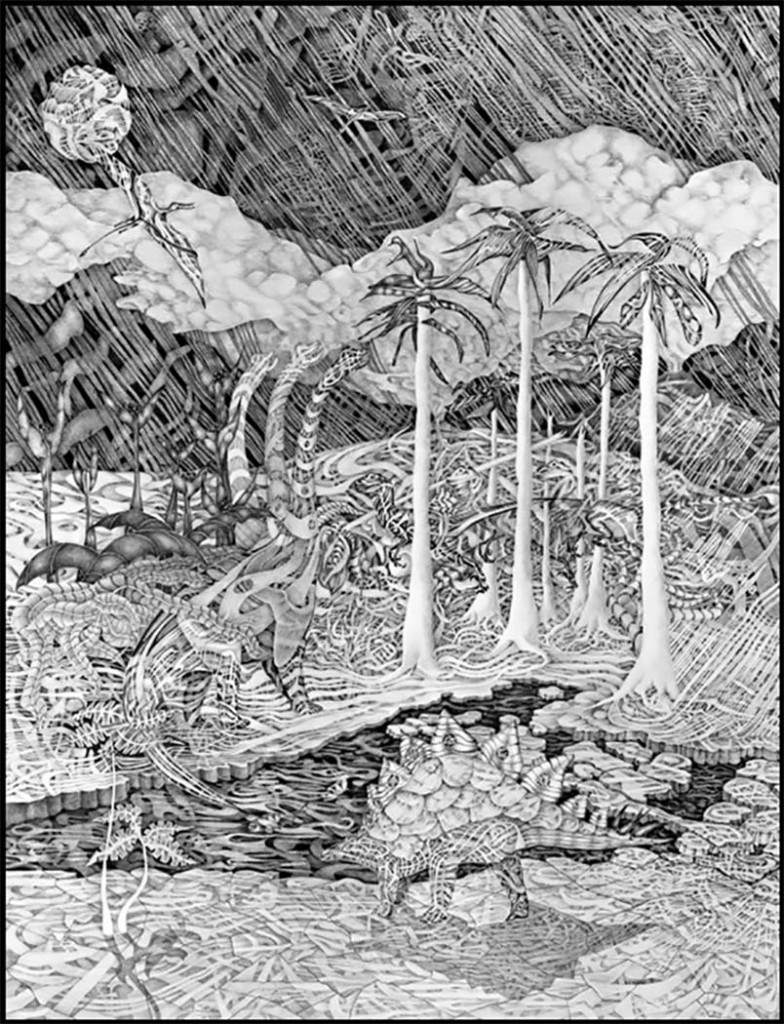

Dino Landscape: Artwork by John Watts

Don Q: Artwork by John Watts

Portrait of Joyce: Artwork by John Watts

Leave a Reply