Philip Reid & The Statue of Freedom and Michelle Browder, Mothers of Gynecology

Philip Reid and The Statue of Freedom

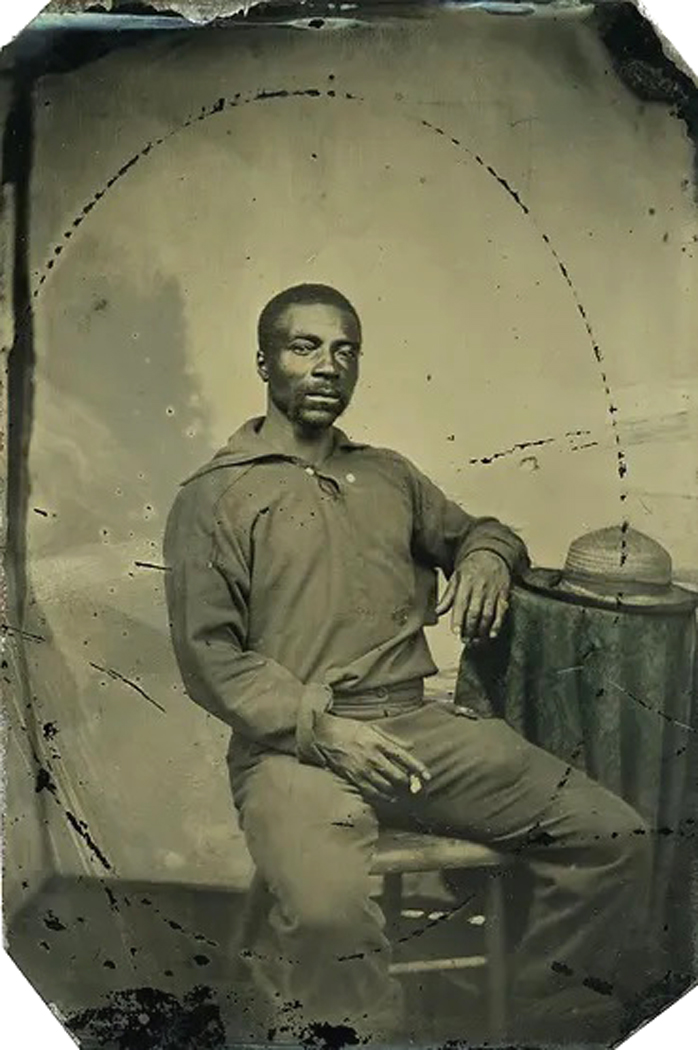

Philip Reid (c. 1820 — February 6, 1892) was an African American master craftsman and artisan who played a key role as the foreman in the casting of the Statue of Freedom sculpture atop the United States Capitol building in Washington D.C. He was born into slavery in South Carolina’s historic city of Charleston.

Philip Reid (c. 1820 — February 6, 1892) was an African American master craftsman and artisan who played a key role as the foreman in the casting of the Statue of Freedom sculpture atop the United States Capitol building in Washington D.C. He was born into slavery in South Carolina’s historic city of Charleston.

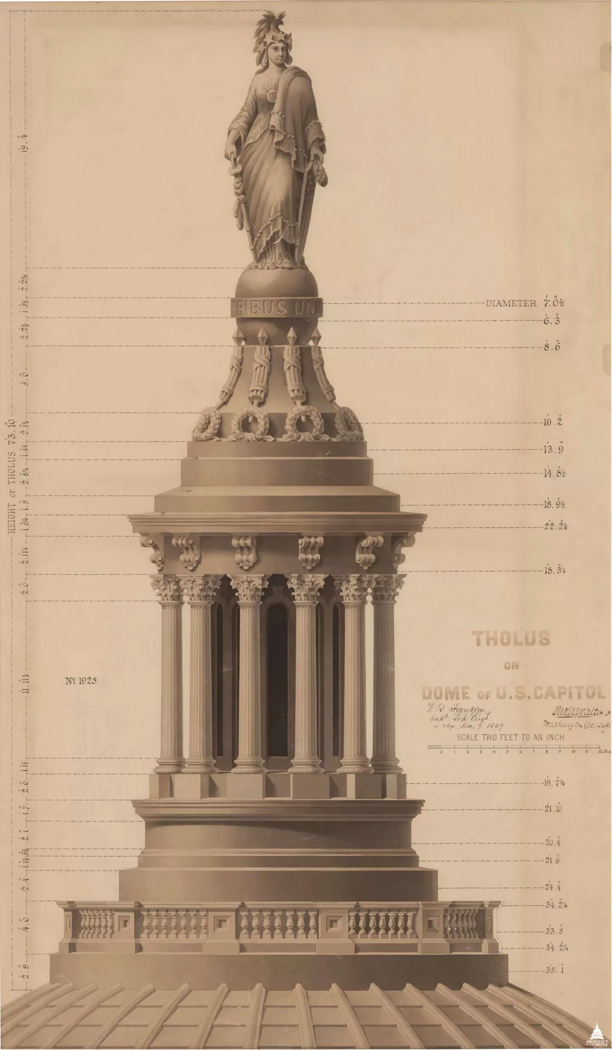

Commissioned in 1855, the initial full-size plaster model of Freedom was completed by American sculptor Thomas Crawford in his studio in Rome, Italy, but he died suddenly in 1857 before it left his studio. Shipped by his widow, packed into six crates, it finally arrived in Washington in late March 1859 and was then assembled and put on display in the Old Hall of the House, now National Statuary Hall.

In May 1860, self-taught sculptor Clark Mills was awarded the contract by the Secretary of War to cast Freedom at his foundry off Bladensburg Road, just inside the District of Columbia. In June 1860, casting of the statue began. The first step was to disassemble the plaster model for the statue into its five main sections in order to move it from the Capitol to the foundry. After its arrival at the Capitol an Italian sculptor, according to Mills’ son Fisk, was hired to assemble it.

However, when the time came to separate the sections, the Italian sculptor refused to help unless given a pay raise. Fortunately, Philip Reid figured out that using a pulley and tackle to pull up on the lifting ring at the top of the model would reveal the joints between the sections. The statue was successfully separated into its five sections and transported to Mills’ Foundry.

The government rented Mills’s foundry for $400 a month and supplied the materials, fuel and labor to cast the statue. Because of this arrangement, the names of the craftsmen and laborers were recorded each day in Mills’ monthly report. Philip Reid was listed as a “laborer” and was paid $1.25 a day, while other laborers were paid $1 day. There is no evidence that any of other men listed as laborers were black or enslaved. An enslaved worker was paid directly if he worked on Sunday; his owner received the payment for his work the other six days. Only Philip Reid was paid directly by the government for working on 33 Sundays.

Amid the Civil War, work on Freedom continued. Arriving in pieces, she was cast at the Clark Mill’s Foundry near Bladensburg, Maryland, under the care, ironically, of a mulatto slave.

On April 16, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed an act abolishing involuntary servitude in the District of Columbia, and district slave owners were allowed to petition for compensation. Clark Mills petitioned for compensation for eleven slaves, including Philip Reid, and included a description of Reid in the petition. Mills wrote that Reid was “aged 42 years, mullatto [sic] color, short in statue, in good health, not prepossessing in appearance but smart in mind, a good workman in a foundry…” Mills asked $1500 for Reid, but received only $350.40.

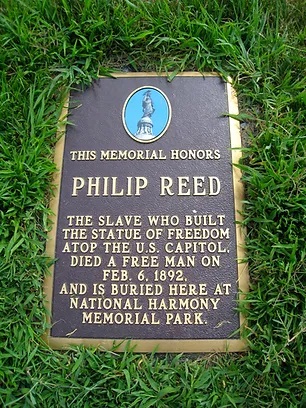

It is not known if Reid witnessed the assembly of the Statue of Freedom atop the Capitol Dome, but he was a free man when the last piece was put into place in December 1863. Two years later, in 1865, author S.D. Wyeth wrote in The Federal City, “Mr. Reed [as his name was spelled during the rest of his life], the former slave, is now in business for himself, and highly esteemed by all who know him.” Afterwards he was listed as “Philip Reed” in city directories and census records as a “plasterer.” In 1870 he was listed along with a wife, Jane, whom he had married in June 1862, and a two-year-old son. In 1880 his wife was listed as Mary P., a laundress.

Death records state that he lived into his seventies and died on February 6, 1892. Though he was initially laid to rest at Graceland Cemetery within view of the Capitol, research revealed that Philip Reid was disinterred and reburied in Columbian Harmony Cemetery in 1895. This cycle repeated itself when he was disinterred and reburied in National Harmony Memorial Park in 1959. On April 16, 2014, the 152nd anniversary of Emancipation in Washington, D.C., a memorial plaque was dedicated to Philip Reed in the cemetery that is now his final resting place.

In an address to Congress 70 years later, a long-time admirer of Lady Freedom, William A. Cox, recalled the facts surrounding Freedom’s construction:

“… the facts are that [Freedom’s] successful taking apart and handling in parts as a model was due to the faithful service and genius of an intelligent negro in Washington named Philip Reed (sic), a mulatto slave owned by Mr. Clark Mill, and that much credit is due him for his faithful and intelligent services rendered in modeling and casting America’s superb Statue of Freedom, which kisses the first rays of the aurora of the rising sun as they appear upon the apex of the Capitol’s wonderful dome.” (Congressional Record (1928), 1200)

For more information, please visit the following link:

For more information, please visit the following link:

https://www.bacast.cok2pm/phillipreid

Philip Reed also Philip Reid (c. 1820 – February 6, 1892) was an African American master craftsman who worked at the foundries of self-taught sculptor Clark Mills, where historical monuments such as the 1853 equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson in Lafayette Square, near the White House in Washington, D.C., the 1860 equestrian statue of George Washington in Washington Circle, and the 1863 Statue of Freedom in Washington D.C., were created. [1] He was born in c. 1820 into slavery in South Carolina‘s historic city of Charleston and was emancipated on April 16, 1862, under the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act[2] After his emancipation, he assisted Mills in installing the Statue of Freedom atop the United States Capitol, which was completed on December 2, 1863. Reid began working as an enslaved apprentice to Mills in 1842, as a young man in his twenties, who was already recognized for his talents in the foundry industry. In the 1860s, after having worked at the foundry for almost two decades, Reid’s skills in working with bronze casting were recognized. In 1928, Tennessee Representative, Finis J. Garrett presented a paper honoring Reid for his “faithful service and genius”, and describing the key role he had played in casting the statue of Freedom, that is now part of the Congressional Record.[3][4] A memorial plaque honoring Philip Reed[Notes 1] was unveiled on April 16, 2014—the 152nd anniversary of Emancipation in Washington, D.C.—in the National Harmony Memorial Park in Hyattsville, Maryland. It reads, “Philip Reed The slave who built the Statue of Freedom atop the U.S. Capitol died a free man on February 6, 1892 and is buried here…”[5] In 2013, he was described by the Architect of the Capitol as the “single best known enslaved person associated with the Capitol’s construction history”.[6]

Background[edit]

Reid—who was an enslaved African American from South Carolina—was born in c. 1820, and became enslaved to Mills when Reid was about 22-years-old, according to the 1864 petition made by Mills for compensation, after slavery had been abolished.[4] Reid remained enslaved to Mills for over twenty years, and was finally emancipated in 1863.

Reviews of Philip Reid’s contributions[edit]

In 1863, with the Statue of Freedom newly installed on the Capital, a newspaper correspondent wrote, “The black master-builder lifted the ponderous uncouth masses and bolted them together, joint by joint, piece by piece, till they blended into the majestic ‘Freedom’…. Was there a prophecy in that moment when the slave became the artist and with rare poetic justice, reconstructed the beautiful symbol of freedom for America?” The Senate Historical Office reprinted these words in their tribute to Reid—”Philip Reid and the Statue of Freedom”—which is part of their series, The Civil War: The Senate’s Story.[2]

During the 70th United States Congress in 1928, Tennessee Representative, Finis J. Garrett, submitted a paper by William A. Cox, describing Reid as an “intelligent negro”, a “mulatto”,[3][4] whose “faithful service and genius” led to the “successful taking apart and handling” of the Freedom statue.[3]

The 1928 Congressional Record Cox’s description of Reid’s role in constructing Freedom. [3]:?1199–1200? Fox, who was a long-time admirer of the Statue of Freedom, said that it had arrived in pieces and was cast at the Clark Mill’s Foundry near Bladensburg, Maryland, under the care, ironically, of a mulatto slave. [3]:?1199–1200?

“… the facts are that [Freedom’s] successful taking apart and handling in parts as a model was due to the faithful service and genius of an intelligent negro in Washington named Philip Reed (sic), a mulatto slave owned by Mr. Clark Mill, and that much credit is due him for his faithful and intelligent services rendered in modeling and casting America’s superb Statue of Freedom, which kisses the first rays of the aurora of the rising sun as they appear upon the apex of the Capitol’s wonderful dome.”

—?William A. Cox. Congressional Record. 1928:1200

The Architect of the Capitol described Reid as the “single best known enslaved person associated with the Capitol’s construction history”.[6]

For more information, please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Reid

How an enslaved man helped create these iconic monuments in Washington, D.C.

PBS NewsHour 3,265 views Feb 18, 2023

Some of Washington, D.C.’s most familiar landmarks were built with the labor of enslaved people, their accomplishments largely lost to history. In part three of our series, “Hidden Histories,” we learn about one of those enslaved laborers, a sculptor named Philip Reid. Stream your PBS favorites with the PBS app: https://to.pbs.org/2Jb8twG Find more from PBS NewsHour at https://www.pbs.org/newshour Subscribe to our YouTube channel: https://bit.ly/2HfsCD6 Follow us: Facebook: http://www.pbs.org/newshour Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/newshour Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/newshour Subscribe: PBS NewsHour podcasts: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/podcasts Newsletters: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/subscribe

Michelle Browder, Mothers of Gynecology

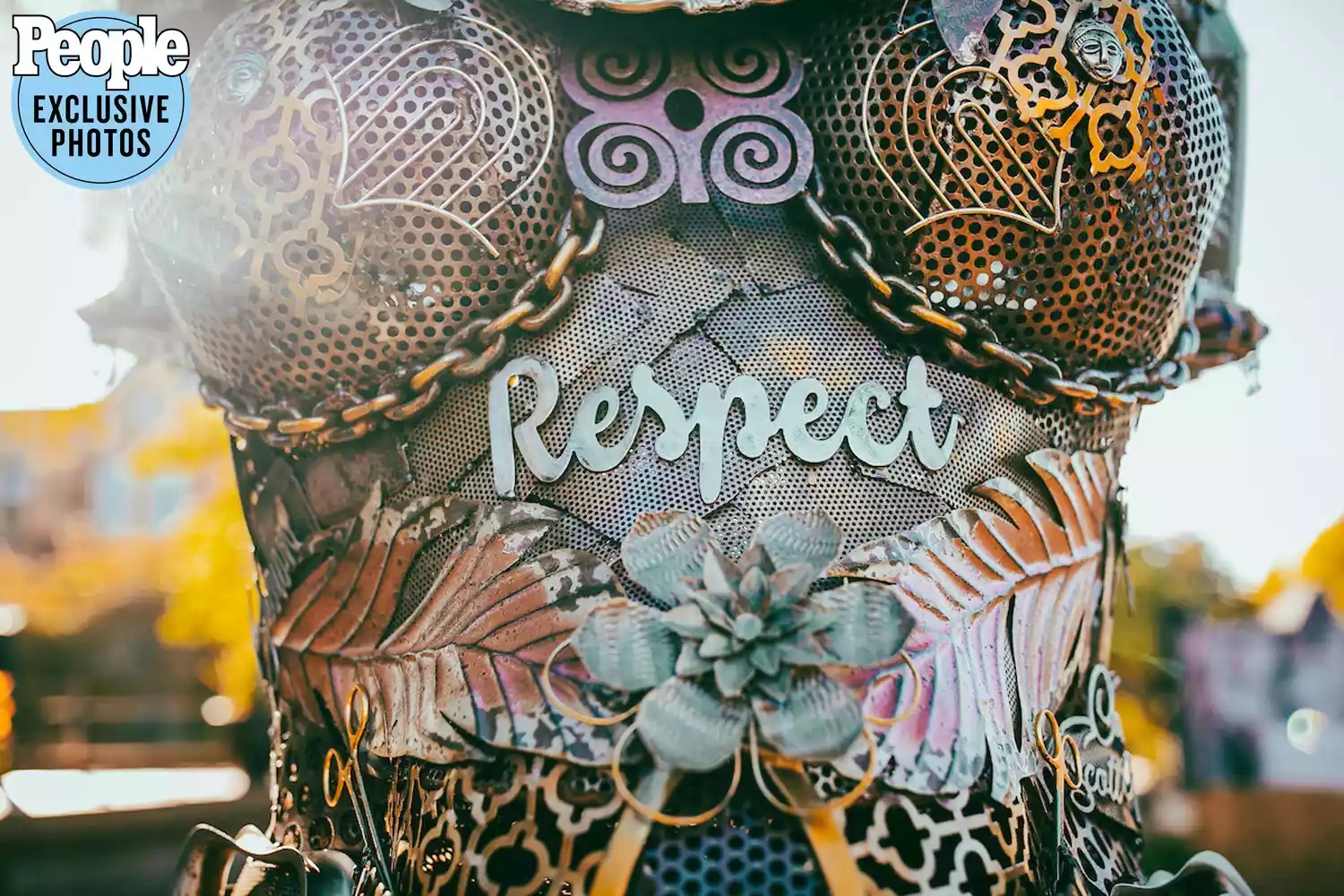

Michelle L. Browder (with Deborah Shedrick), Mothers of Gynecology, 2021, found metal objects and other media, roughly 15 feet high (Mission for More Up campus Montgomery, Alabama, © Michelle L. Browder)oint

Michelle L. Browder (with Deborah Shedrick), Mothers of Gynecology, 2021, found metal objects and other media, roughly 15 feet high (Mission for More Up campus Montgomery, Alabama, © Michelle L. Browder)oint

- Artist and activist Michelle Browder’s monument reclaims the history of the enslaved Black women who underwent non-anesthetized medical experimentation by Dr. James Marion Sims in the late 1840s in Montgomery, Alabama. The monument includes a sculptural group that portrays the only three enslaved women whose names were recorded in Dr. Sims’ documentation of his experiments: Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy. The identities of other enslaved women who suffered under Dr. Sims, whose names he did not record, are unknown.

- James Marion Sims has long been celebrated as the father of gynecology for, among other things, developing a procedure to remedy vesicovaginal fistulas. The excruciating and repeated experimentation on enslaved Black women that led him to perfect this procedure, however, reflects the racist devaluation of Black humanity and prevailing perception of Black people as property in the mid-19th century. Sims justified these experiments in part because he, along with many other white people at the time, believed that Black people didn’t feel as much pain as white people (a racist belief which still impacts medical treatment for Black people today).

- Browder’s monument includes larger-than-life-sized figures of the three women and the displaced womb of Anarcha. The bodies and womb are made from discarded metal materials that reference their inhumane treatment by Dr. Sims and other whites who perpetuated slavery. The women’s postures, hair, and adornments, however, serve to reinstate their identities and celebrate the power and resilience of Black women.

Go deeper

Learn more about the Mothers of Gynecology park at The More Up Campus

Deirdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology (University of Georgia Press, 2017)

More to think about

A 2017 Alabama law, enacted to safeguard Confederate monuments, states that no monuments erected on public property for more than 40 years may be removed. With her ability to advocate for the removal of a 1939 sculpture of Dr. Sims in the city of Montgomery restricted, Michelle Browder chose to make a new monument to reclaim the history of the women upon whom Dr. Sims experimented. Discuss the impact of retaining monuments to individuals who perpetuated harm verses removing them. How can Michelle Browder’s new monument function in relation to the older monument to Sims*? Consider the choices Browder made in materials, size, and composition.

*The Sims monument is discussed and shown in the Mothers of Gynecology video.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Cite this page as: Michelle L. Browder and Dr. Beth Harris, “Michelle Browder, Mothers of Gynecology,” in Smarthistory, March 21, 2022, accessed February 28, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/seeing-america-2/mothers-of-gynecology/.

For more information, please visit the following link:

https://smarthistory.org/seeing-america-2/mothers-of-gynecology/

Artist Michelle Browder Creates ‘Mothers of Gynecology’ Monument to Enslaved Women Who Endured Experiments

Artist Michelle Browder Creates ‘Mothers of Gynecology’ Monument to Enslaved Women Who Endured Experiments

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

The Mothers of Gynecology honored in an …

Monument to ‘Mothers of Gynecology’ unveiled in Montgomery – al.com

Mothers of gynecology statues honor Black women tortured for science

Mothers of gynecology statues honor Black women tortured for science

Artist Michelle Browder Is Soon to Open A Museum and Clinic in Honor of The “Mothers of Gynecology” – America’s Black Holocaust Museum

Artist Michelle Browder Is Soon to Open A Museum and Clinic in Honor of The “Mothers of Gynecology” – America’s Black Holocaust Museum

Mothers of Gynecology, Montgomery, Alabama

Mothers of Gynecology, Montgomery, Alabama

Related content

Monument to ‘Mothers of Gynecology’ unveiled in Montgomery – al.com

Subjected to Painful Experiments and Forgotten, Enslaved ‘Mothers of Gynecology’ Are Honored With New Monument | Smart News| Smithsonian Magazine

Subjected to Painful Experiments and Forgotten, Enslaved ‘Mothers of Gynecology’ Are Honored With New Monument | Smart News| Smithsonian Magazine

Alabama artist works to correct …

Alabama artist works to correct historical narrative around beginnings of gynecology | PBS NewsHour

warning: this video discusses racial violence

Michelle Browder, Mothers of Gynecology

Smarthistory 10,984 views Jan 19, 2022

warning: this video discussed racial violence Michelle L. Browder (with Deborah Shedrick), Mothers of Gynecology, 2021, found metal objects and other media, roughly 15 feet high (Mission for More Up campus Montgomery, Alabama, © Michelle L. Browder) speakers: Michelle Browder and Dr. Beth Harris speakers: Michelle Browder and Dr. Beth Harris

Alabama artist works to correct historical narrative around beginnings of gynecology 8:43 mins

PBS NewsHour 4,720 views Feb 27, 2023

The history of gynecology as a medical specialty has deep roots in the American South, but that legacy is as complicated as the history of the South itself. In partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Montgomery, Alabama, for our arts and culture series, CANVAS, and the series Agents for Change. Stream your PBS favorites with the PBS app: https://to.pbs.org/2Jb8twG Find more from PBS NewsHour at https://www.pbs.org/newshour Subscribe to our YouTube channel: https://bit.ly/2HfsCD6 Follow us: TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@pbsnews Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/newshour Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/newshour Facebook: http://www.pbs.org/newshour Subscribe: PBS NewsHour podcasts: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/podcasts Newsletters: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/subscribe

Leave a Reply