Jacob Landau Artist and Teacher

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacob_Landau_(artist)

Jacob Landau (artist)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

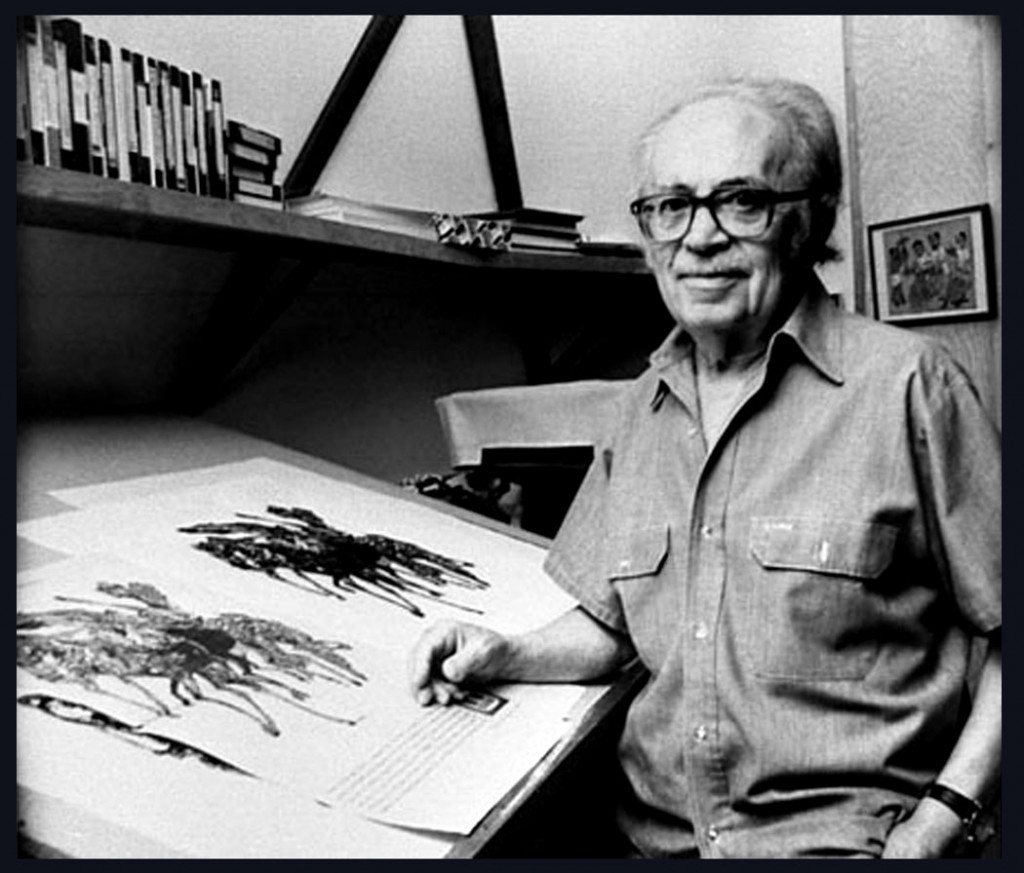

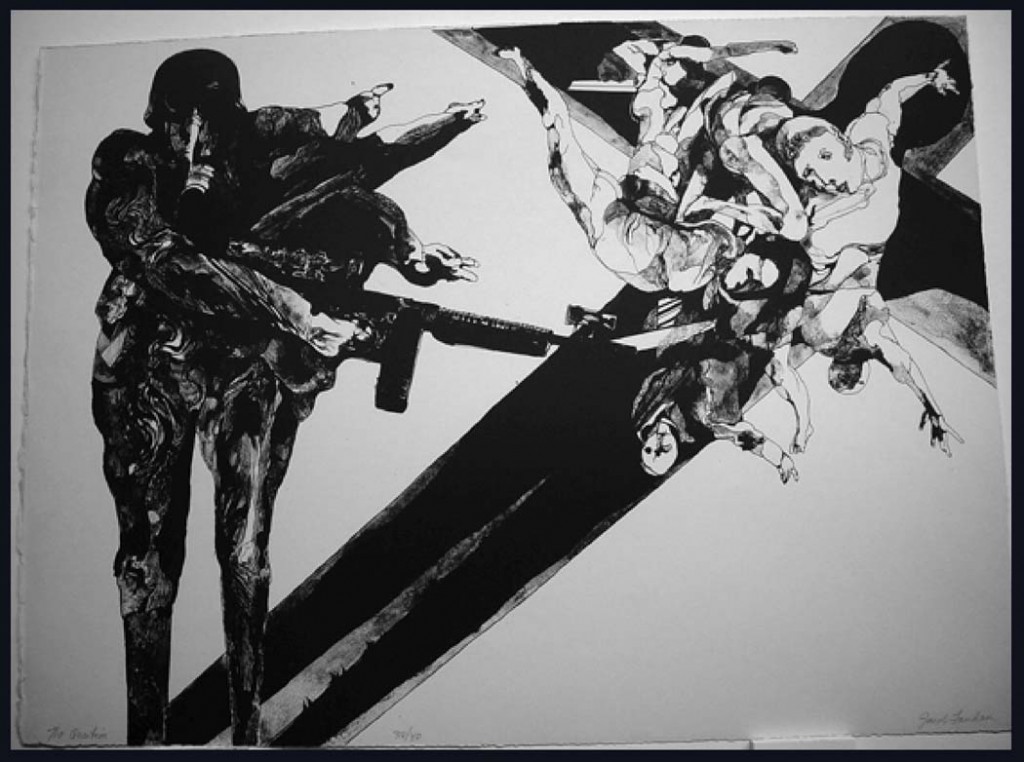

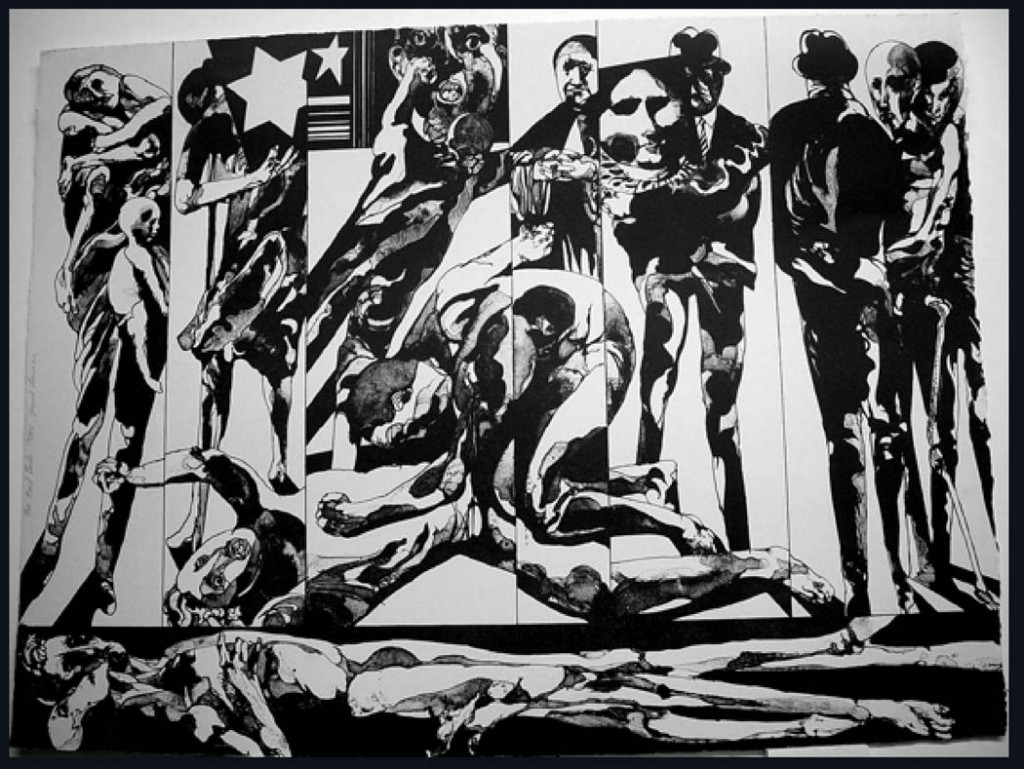

Jacob Landau (December 17, 1917 in Philadelphia – November 24, 2001) was an American artist best known for his evocative works on the human condition. Typically, his works address the Great Depression, World War II, and the impact of technology and politics on individuals and their surroundings. Landau’s works can be found in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, and the National Gallery.

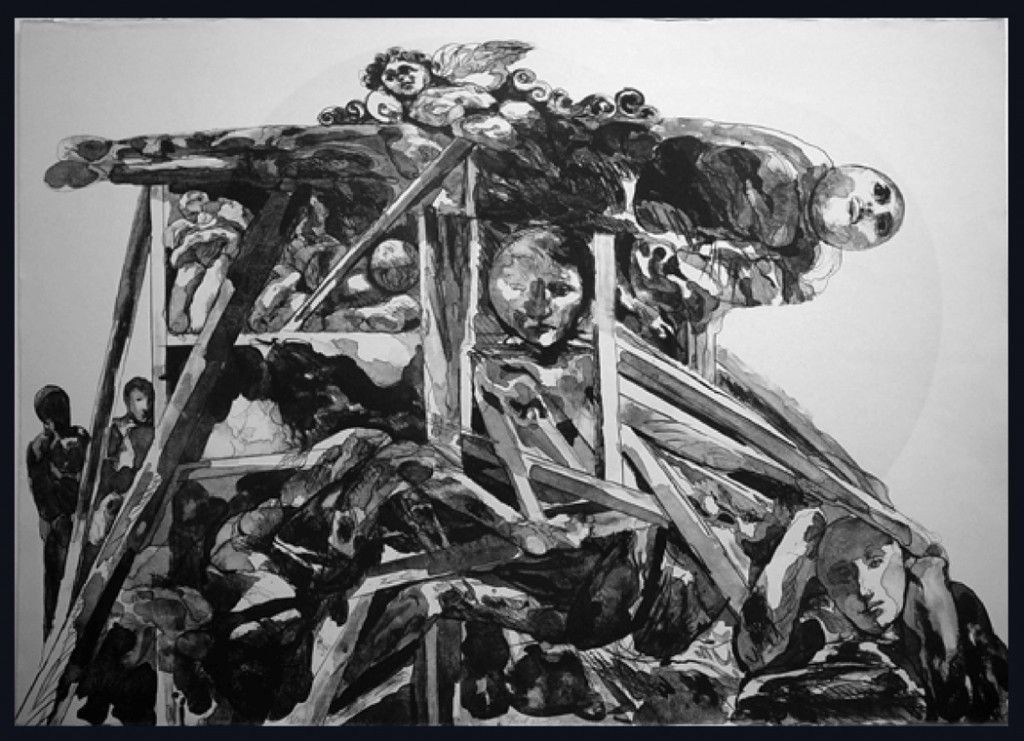

Songs in the Night from the Holocaust Suite Circa 1967

Landau was born December 17, 1917, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. By the age of three he began drawing everything around him. When he was 12, he began studying at the Graphic Sketch Club, now the Samuel Fleisher Memorial.

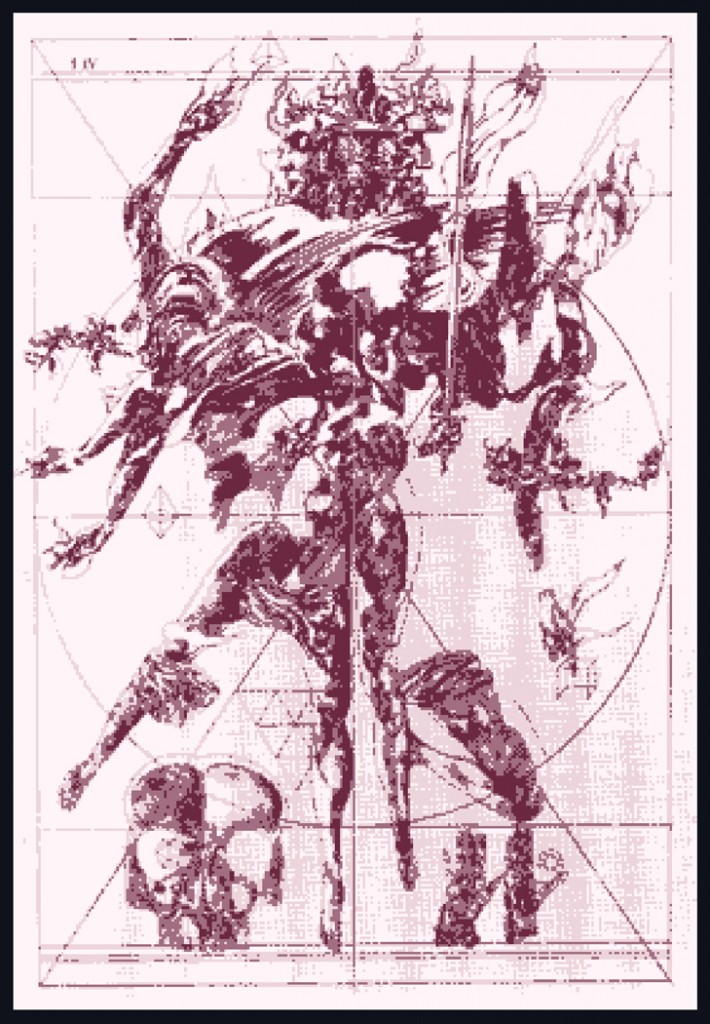

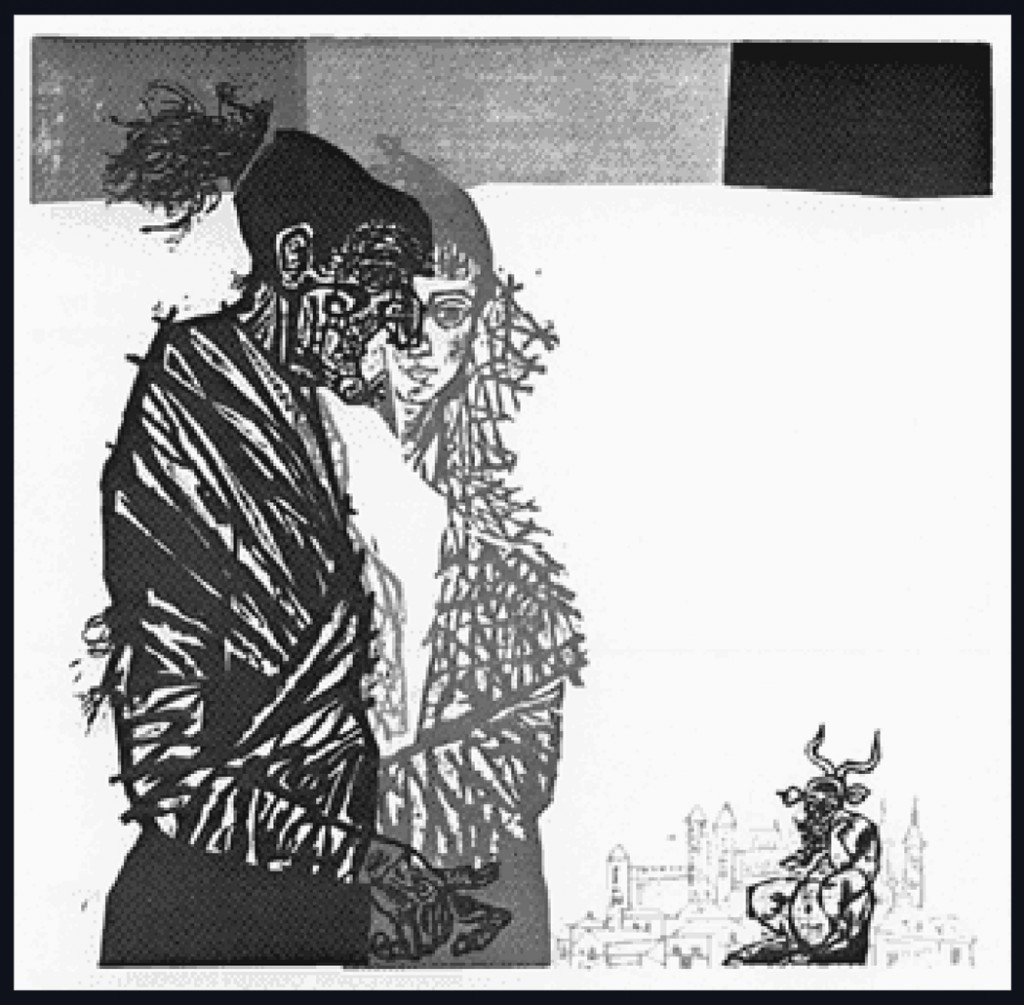

The Question from the Holocaust Suite Circa 1967

At the age of 17, Landau’s illustrations for Kipling’s Jungle Book won a competition in Scholastic Magazine. He won the competition the following year as well. In 1935, Landau received a scholarship from the Museum School of Industrial Art (today the University of the Arts) to study illustration, printmaking and painting.[1]

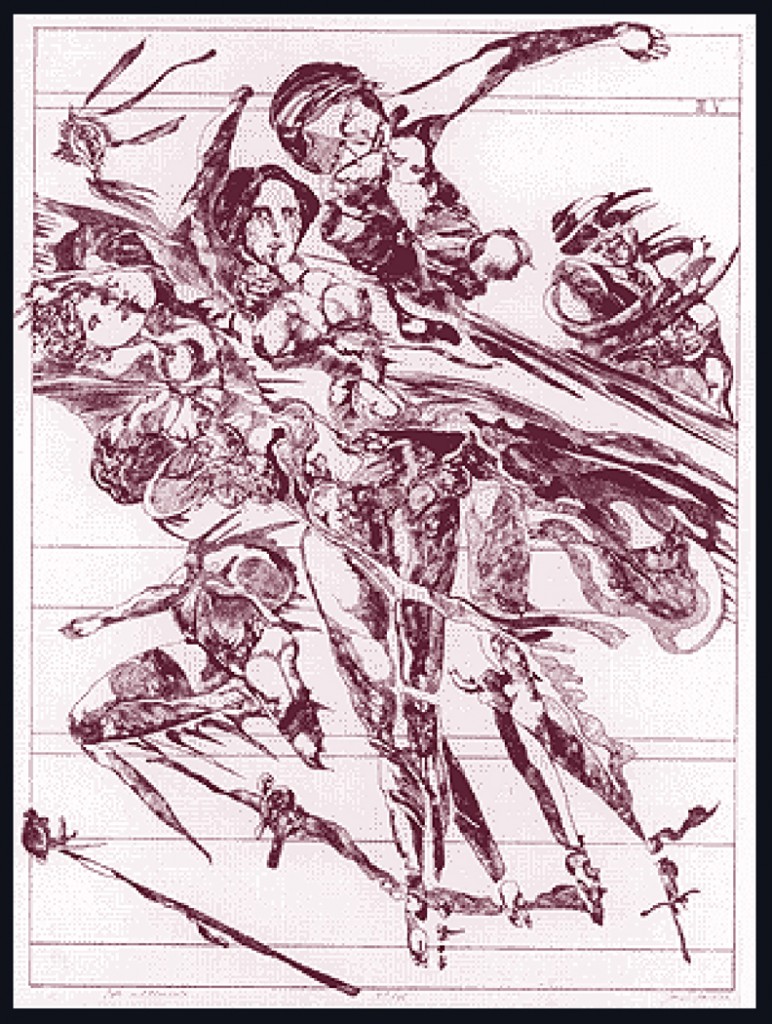

The Road Back from the Holocaust Suite Circa 1967

After his graduation in 1939, Landau moved to New York City where he experimented with a variety of styles, treatments and media. His first phase as a professional artist included illustrating books and magazines.

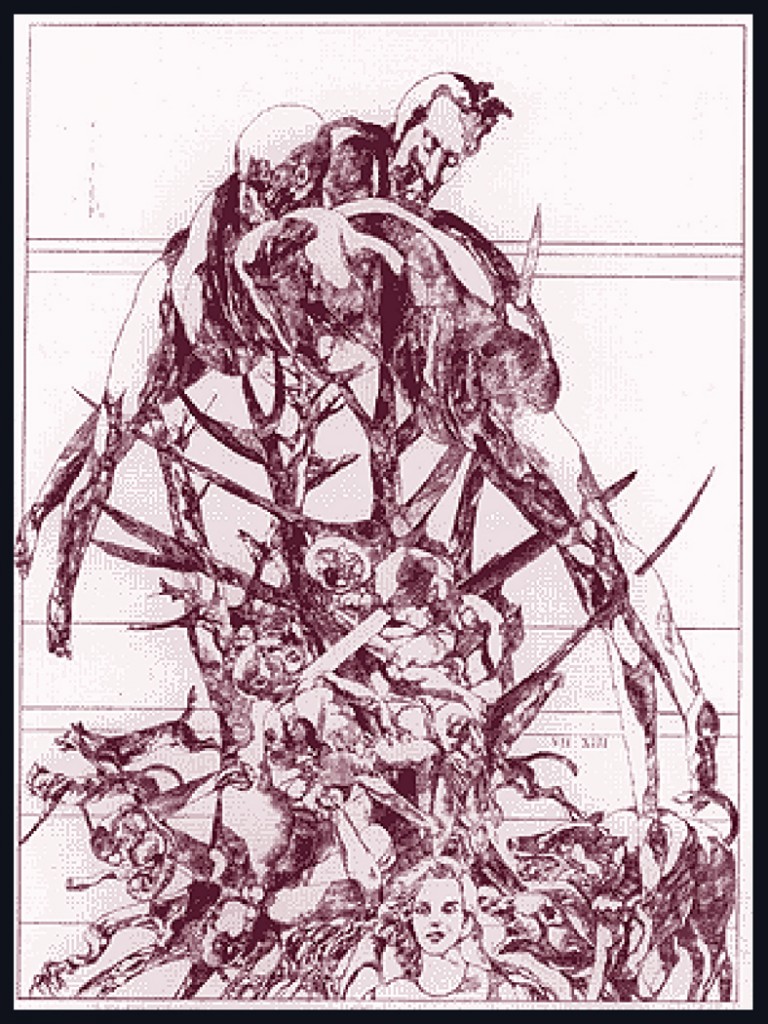

Man’s End from the Holocaust Suite Circa 1967

In 1943, Landau was drafted into the armed forces, serving two years overseas in the Mediterranean Theater. In the army, Landau served in a number of capacities which utilized his artistic talents. His service in Italy included work as the art editor, photographer, and reporter of At Ease, a special services magazine. After his discharge in 1946, Landau used the G.I. Bill to further study art.

The Geography of Hell from the Holocaust Suite Circa 1967

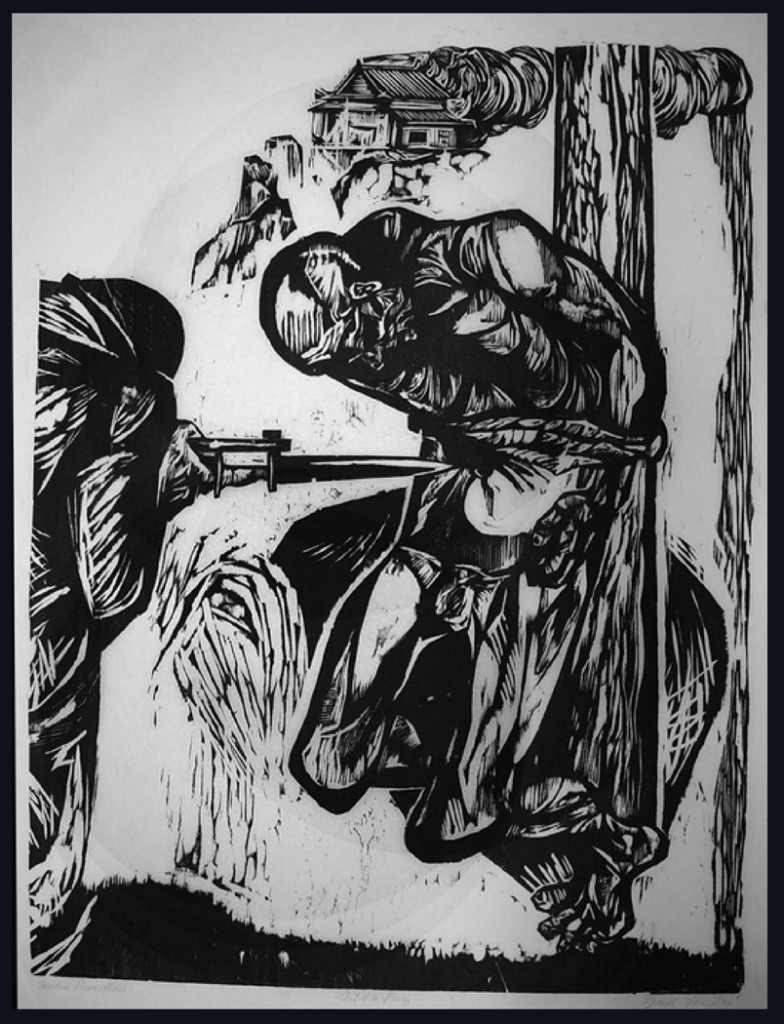

Landau spent a year (1948-1949) at New York’s New School for Social Research before moving to Paris with his wife, Frances, and young son to study at the Academie Julian and the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere. While in Paris, Landau met printmaker Leonard Baskin, who taught him the medium of woodcuts.[1]

Holocaust from the Holocaust Suite Circa 1967

From 1954-1957 Landau taught at the Philadelphia College of Art before moving to Pratt Institute where he would teach for over 20 years. During his time at Pratt, Landau helped to establish the University Without Walls program, in which students worked closely with instructors to gain hands-on experience. In 1975, Landau became a faculty member of the Artist Teacher Institute, a 10-day summer residency program sponsored by the New Jersey State Council on the Arts.

The Mark of Cain from the Holocaust Suite Circa 1967

The Mark of Cain from the Holocaust Suite Circa 1967

In addition to his art and teaching, Landau was very involved in the community. He was active in many different organizations including: Alliance for Arts Education, American Humanist Association, Association for Humanistic Psychology, Coalition for Nuclear Disarmament, International Arts Association, Jewish Federation, Linkage Project, New Jersey School for the Arts, Printmaking Council, and World Futures Society. In 1974 he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member and became a full Academician in 1979.

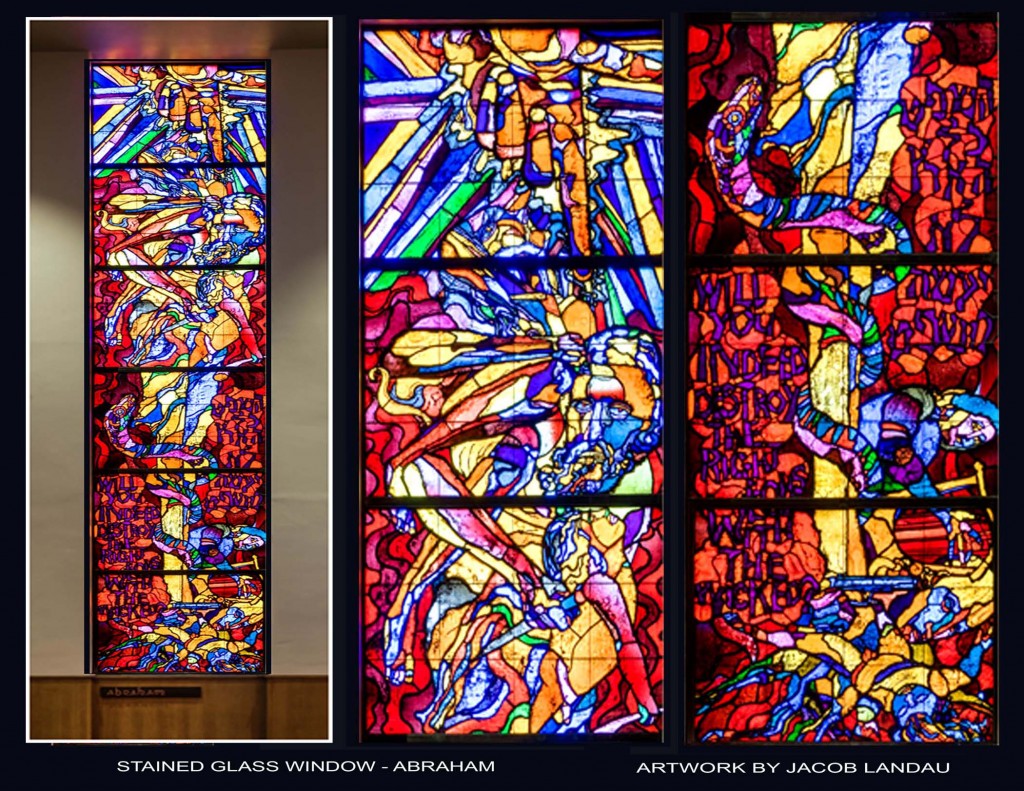

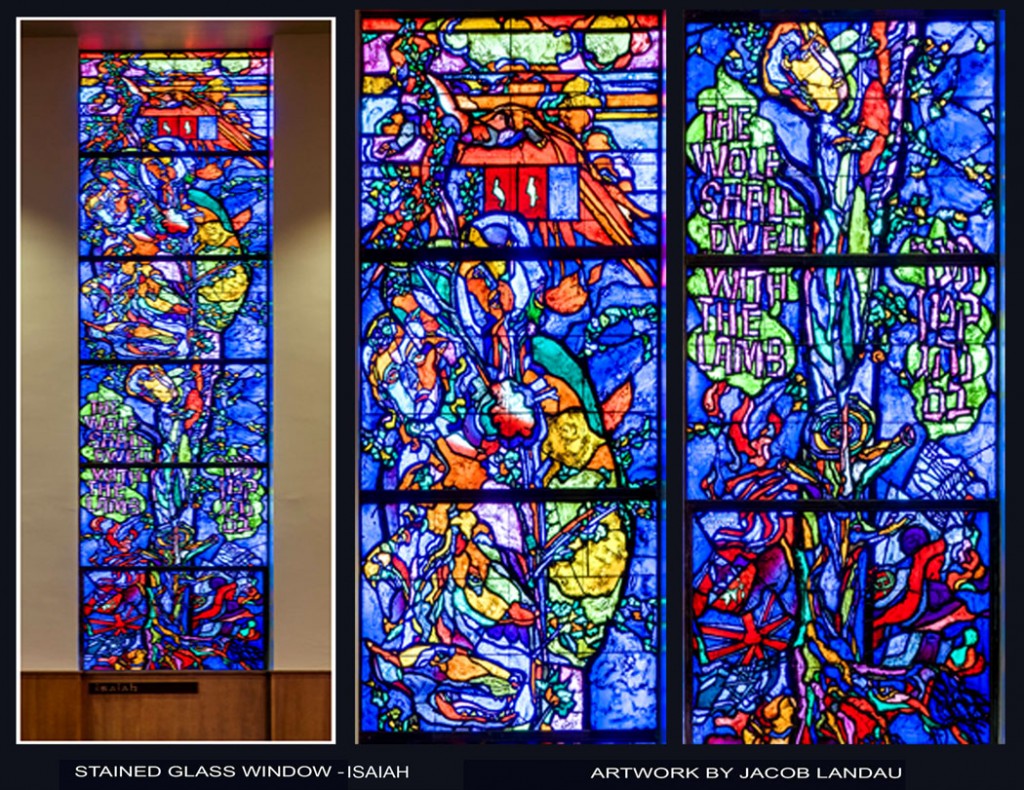

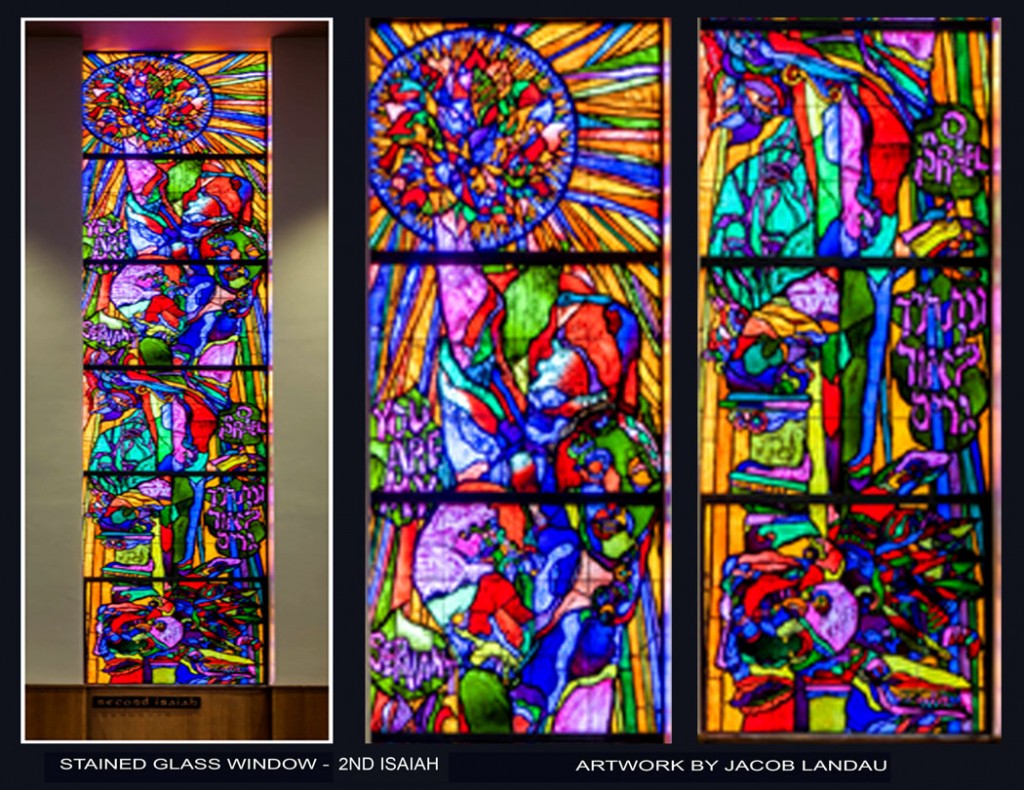

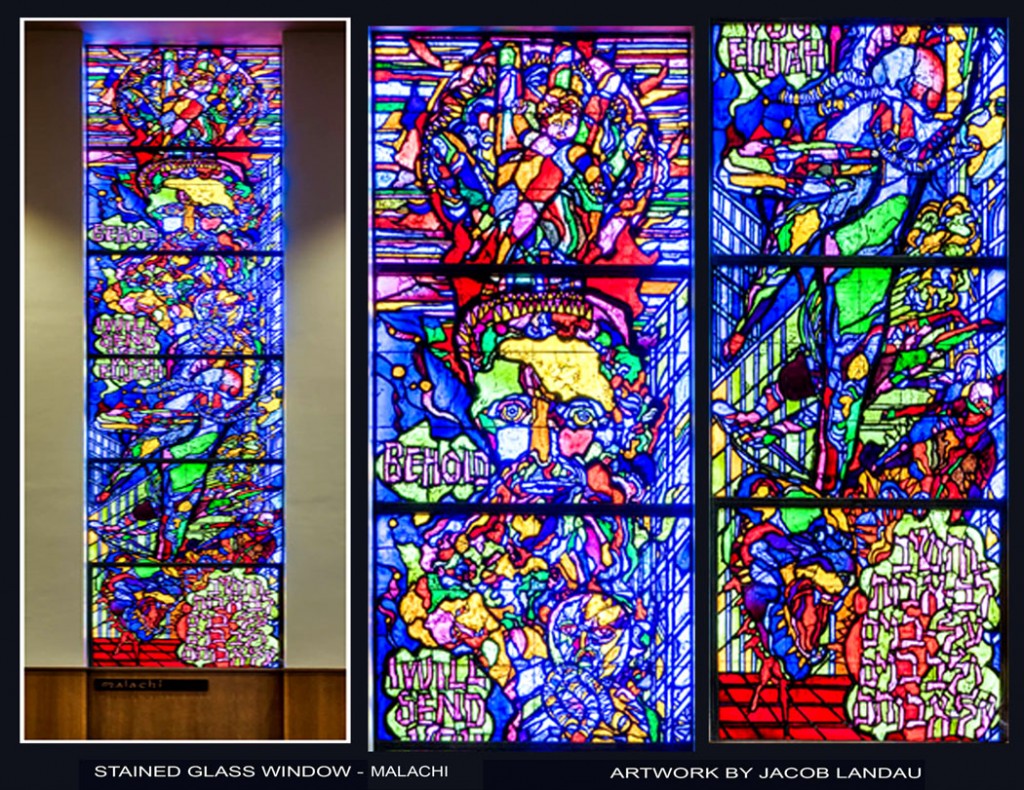

STAINED GLASS WINDOW – EZEKIEL

The Willet Hauser Studios association with Jacob Landau began when he was commissioned by Keneseth Israel Reform Synagogue in Philadelphia to create paintings that were to be interpreted into stained glass windows. The congregation had conducted a search for a well-known artist to design the windows. Landau’s work deals with the universal concerns of Turmoil, Symbiosis, Love and Grief. His depictions of the scriptural prophets exhibited in his paintings for these windows bring them into the present. He was called a reformist, a visionary as were these prophets.

In that Landau had no previous experience in designing stained glass, Benoit Gisoul translated his drawings into original cartoons and the Willet Hauser Studios fabricated the windows.

A series of ten stained glass windows at

the Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel, Elkins Park, PA

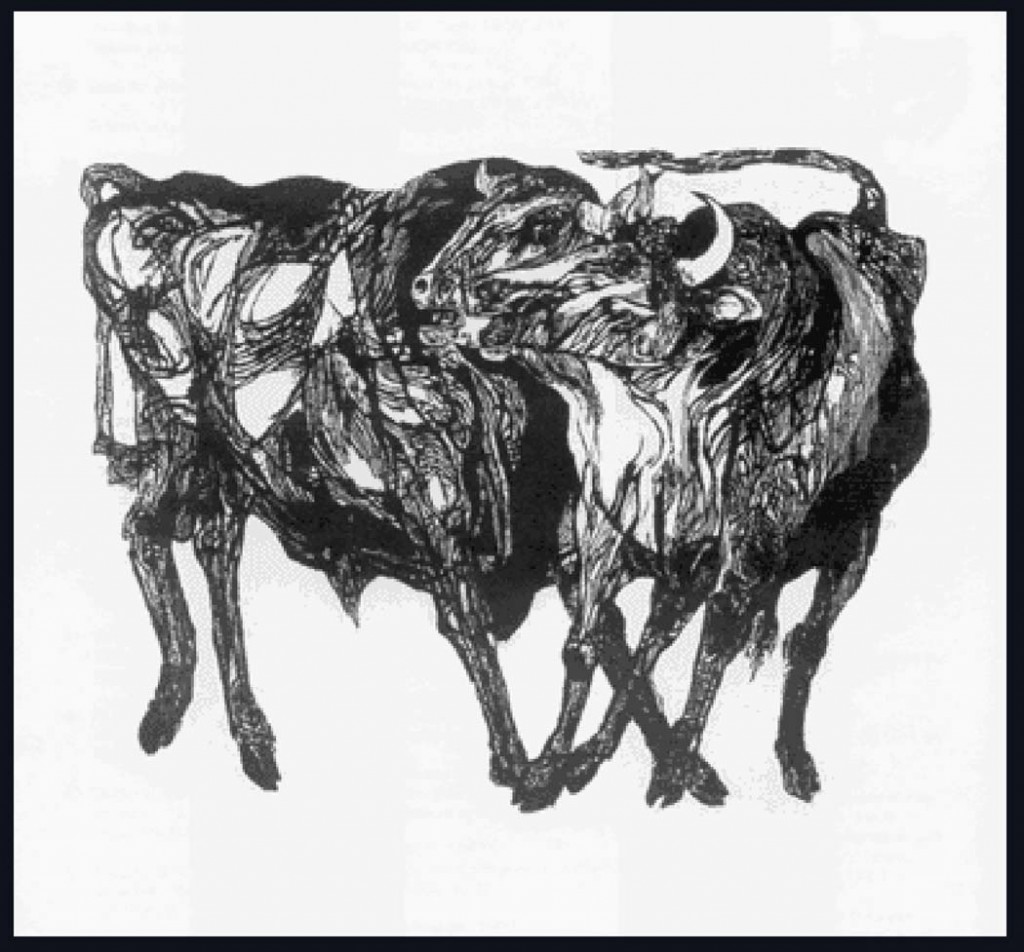

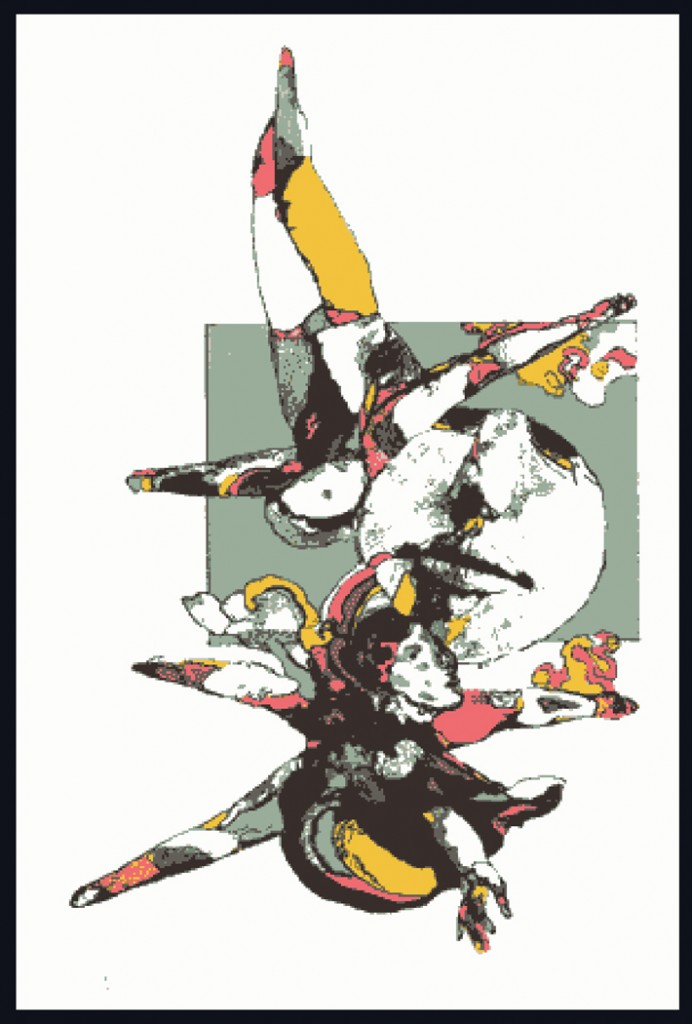

Bulls

Landau and his wife Frances lived in Roosevelt, New Jersey as part of a small community of artists. There he built a geodesic dome which was created as an art studio. His wife died in 1993 of Alzheimer’s Disease. They had two sons, Jonas and Stefan.

Jacob Landau died on November 24, 2001, at the age of 85, and is buried in the Roosevelt Cemetery near his friends Ben Shahn and Gregorio Prestopino.[2] After his death, the Jacob Landau Institute was formed to preserve his legacy, share his unique philosophy of education, and nurture individual artists.[3]

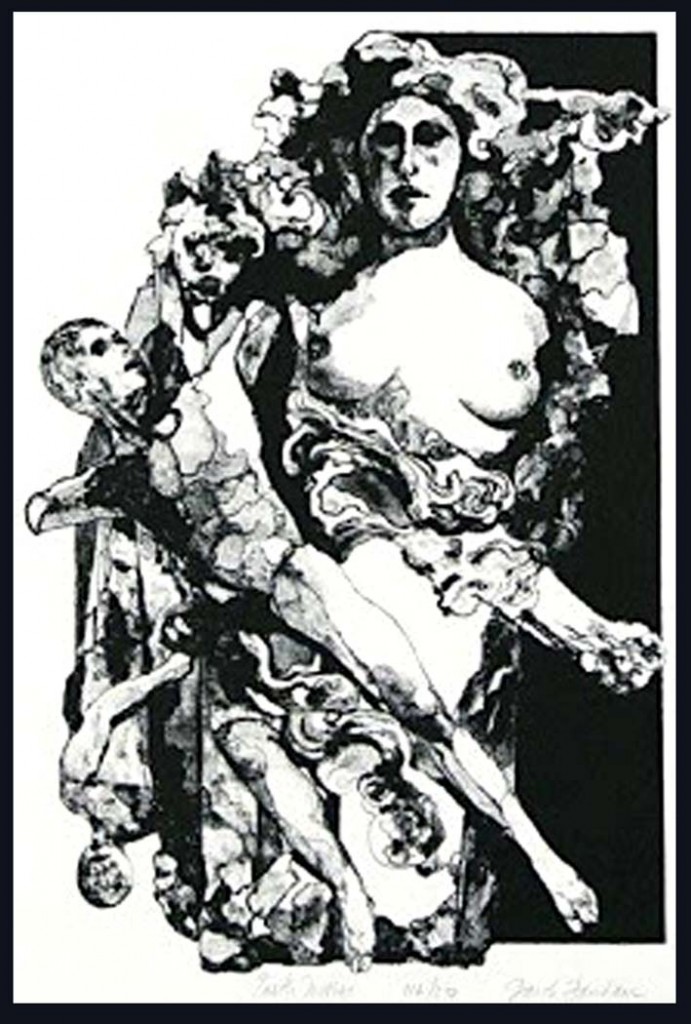

Earth – Mother

Artwork[edit]

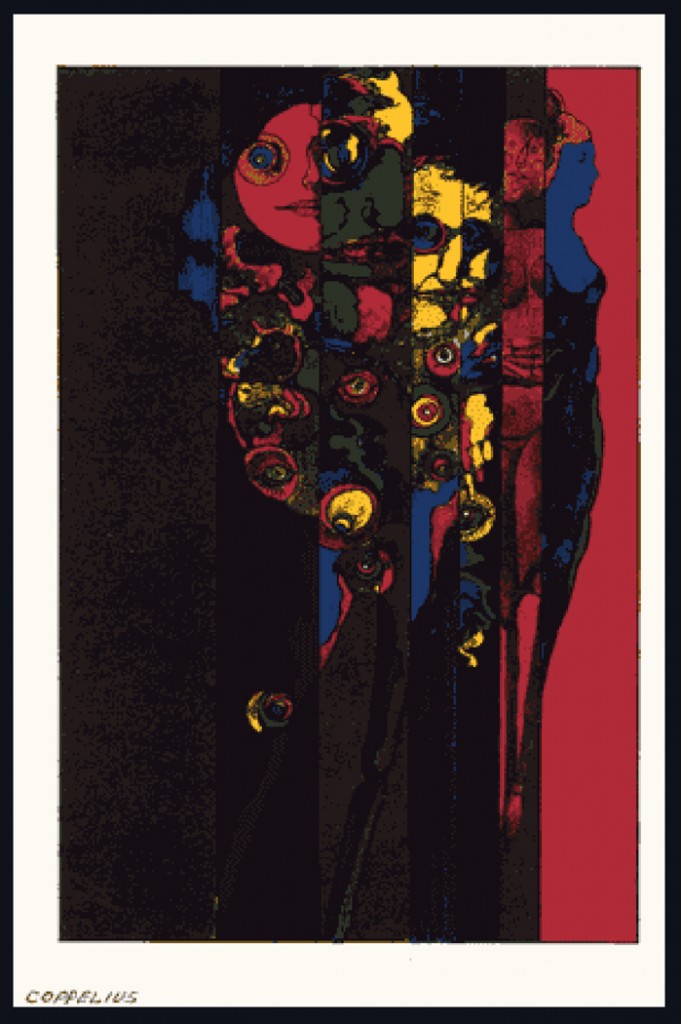

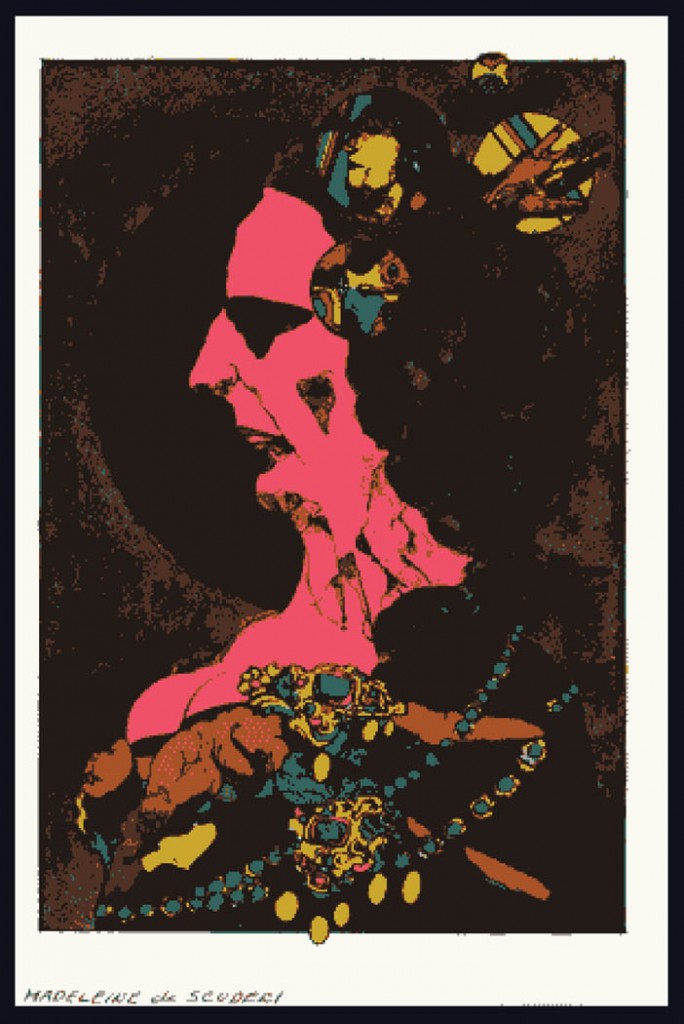

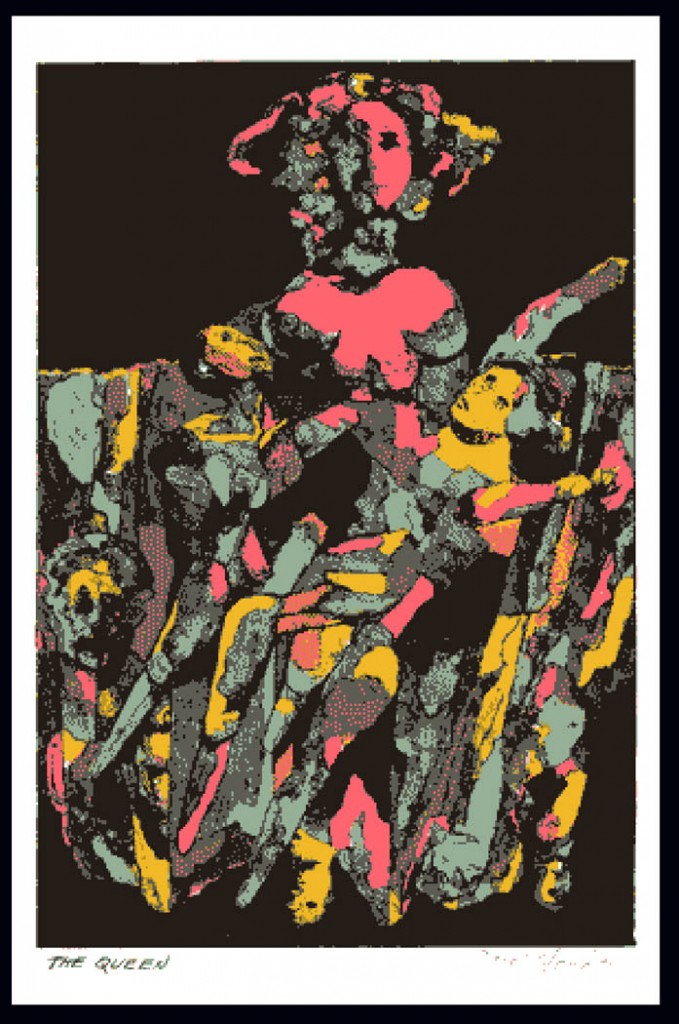

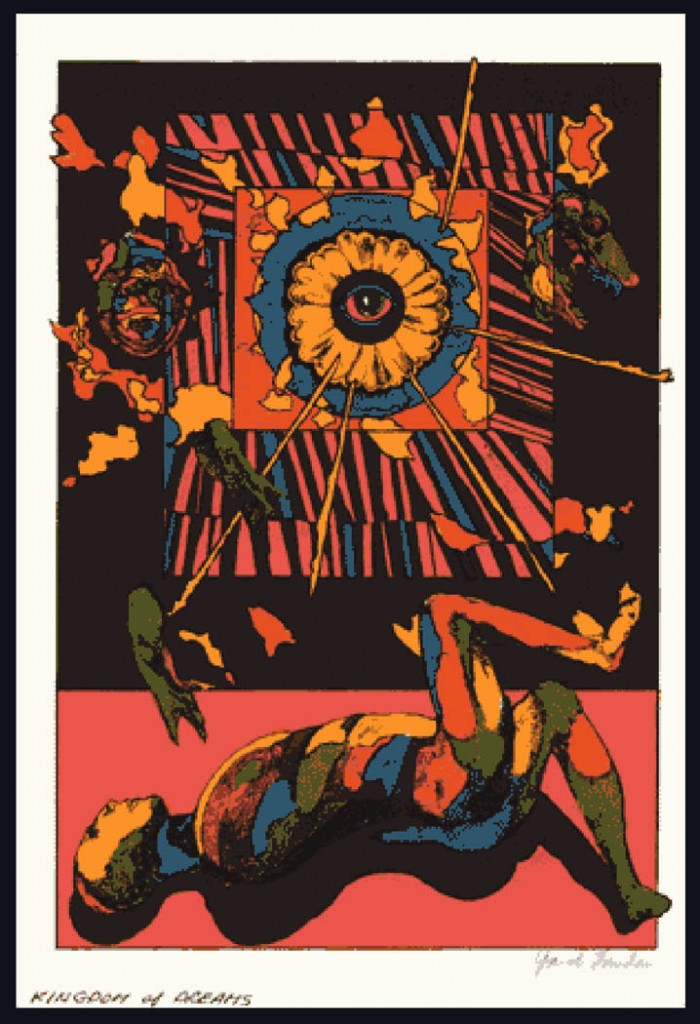

Landau’s art communicates his consciousness of humankind’s predicament, its beauty and its horror.[4] Growing up during the Great Depression and having been profoundly affected by The Holocaust, Landau’s work expresses the self-inflicted human turmoil of the 20th century. He often drew from biblical or literary sources, presenting unpleasant topics in a way that emphasized the unlimited possibilities of peace and greater understanding. Existential philosopher Walter Kauffman described Landau’s work as “unmistakenly modern and at the same time in the tradition of Goya and Blake.”[1]

Clemen

| Distinguished by vigorous creativity and superb craftsmanship, the graphic works of Jacob Landau also reflect his deep intellectual and philosophical concerns as an internationally respected humanist-artist and futures-oriented thinker. While some artists reject objectivity in their work, Landau continues to explore the basic themes of human existence with passionate and indignant insight. |

Appearing below are various comments made by Artist Jacob Landau over the course of his career. His remarks shed insight into the mind of this brilliant and talented artist.

“No revolutionary can ever realize his programmatic aims, because history is the resultant of all factors at work. Hence the need to rearrange history, to destroy those who would spoil the ‘design’.”

STAINED GLASS WINDOW – JEREMIAH

Jacob Landau’s comments

“We need memory above all as a means to bolster or restore self esteem. We count on others to reassure the good things we do, and to reward us for these deeds. Nothing is more unsettling than caring for someone with a loss of memory – each minute is a test, a new beginning. There is no stored-up acknowledgment, no capital, nothing in the bank.”

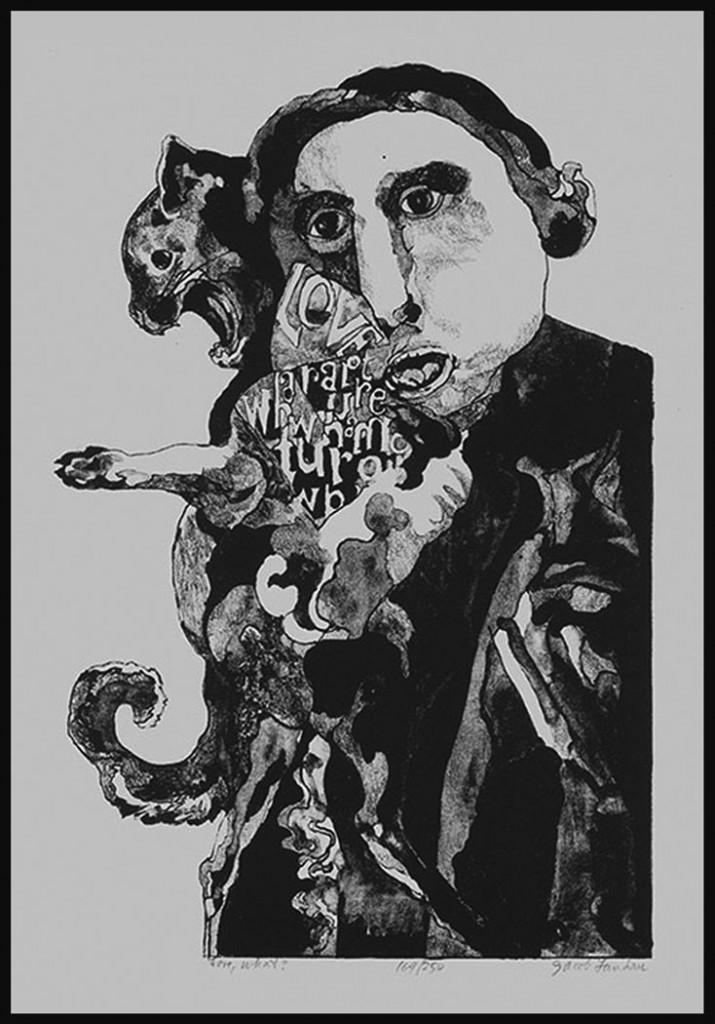

Love

Jacob Landau’s comments

“What’s wrong with all religion is the assumption that each is universal – and universally good. Each postulates a utopia – but each, in direct proportion to the amount of secular power, creates a hell.”

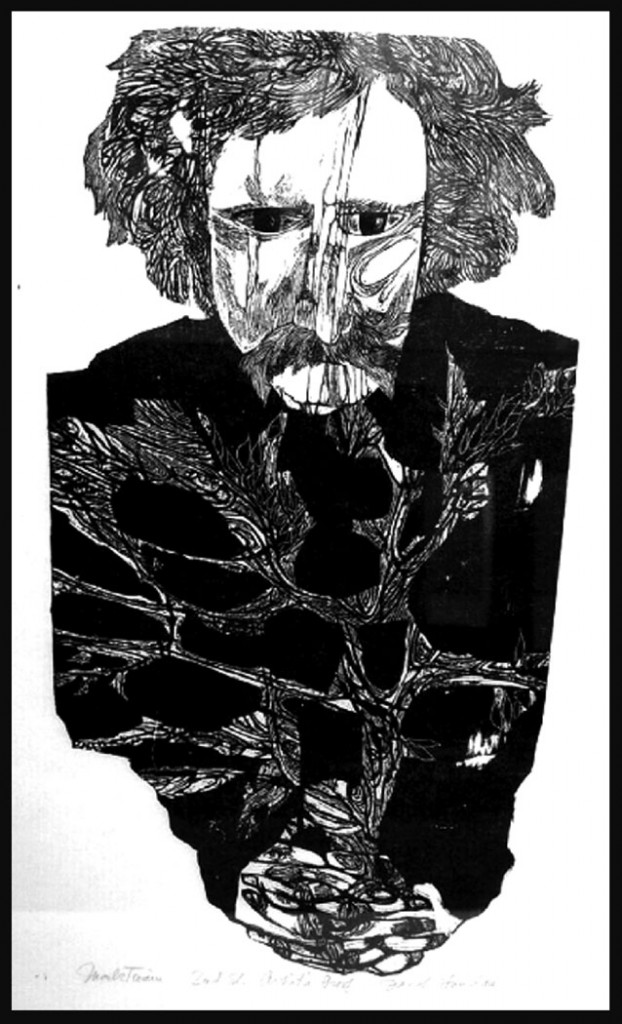

Mark Twain

Jacob Landau’s comments

“We live in the fallen world of crimes and punishments, the endless round of atrocities. Does the punishment fit the crime, as in Dante’s comedy? Then the punishment is also a crime. And so it goes, toward the ultimate crimes of genocide and ecocide, each crime a punishment, each punishment a crime.”

Eagles

Jacob Landau’s comments

“Without Chochmah, there is no justice. Without justice, the law is repression. We all break laws, the poor or powerless get caught. The powerful often can arrange the laws to suit themselves yet the greatest law breakers are the nation–states who perpetrate the DRESDENS, the HIROSHIMAS, the DACHAUS.”

STAINED GLASS WINDOW – ELIJAH

Jacob Landau’s comments

“The Judeo-Christian “Problematique” Choose: Either no chastisement for sin (no sin) or infinite regress to original sin (all is sin/all is chastisement for sin). Catastrophes become necessary as chastisement fore ordained. So God is evil, God is chastisement, God is catastrophe, history is catastrophe. We need catastrophe to bring us to God and the “true” faith. History is punishment for sin. Holocaust is God’s will. Anger is God’s style. Is God then the storm trooper, the pogromist, the destroyer, friend and ally of the wicked, punisher of the righteous? Where then is Divine Justice? The archetype of wrath is the flip-side of the archetype of love. Christ of the Apocalypse is the shadow of Christ of the Gospels.”

Dante 01

Jacob Landau’s Comments

“The Spiritual perspective – hierarchy seen as “the higher is the better” – mind over matter, brain over body, spirit versus bodily functions (soul versus sex), life of the mind as better than mindless life (so people are more important than animals, trees, the ocean), the rational over the emotional, adults superior to children, men to women (i.e. men are more “abstract” “rational”, women are involved with their feelings). “civilized” are better than ” primitive”. All religion is based on variations of this perspective. D.H. Lawrence knew better!”

Dante 02

Jacob Landau’s Comments

“Thou shalt not kill”, we say, except when authorized by the state. And so the slaughter goes on, one hundred million in this century alone, and still counting. And death is not enough. We humans are the only creatures on earth who practice torture.”

Dante 03

Jacob Landau’s Comments

“The literal adherence to a particular rule of what is thought to be good almost always results in unmitigated evil.”

STAINED GLASS WINDOW – HOSEA

Jacob Landau’s Comments

“Are we performers in relation to scenarios of mystic proportions – ARCHETYPES, root metaphors – or are we play things of fate? Are we heroes or victims, winners or losers? Do we form ourselves or are we formed? In whose book are we characters?”

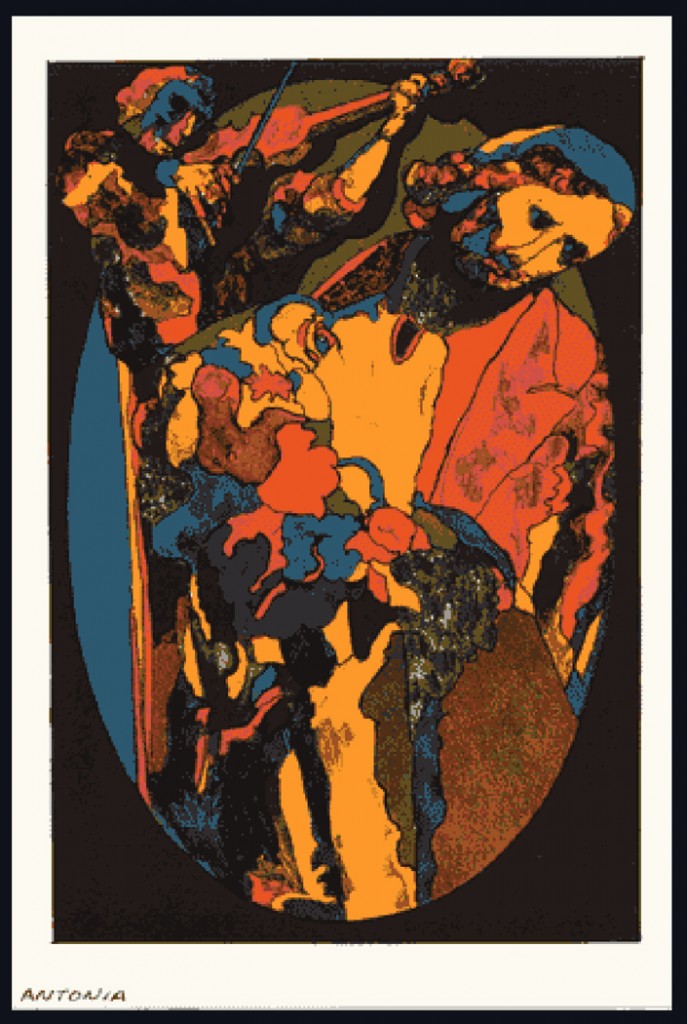

Antonia

Jacob Landau’s Comments

“Theoretically an adult is someone who can exist in the physical world without a lot of supportive devices. In the cybernetic womb, however, we are all infantilized, the technological placenta is our garden of delights.”

Jacob Landau’s Comments

“Art is re-creation, a second coming, resurrection of past life, of things dead and gone. Creative living is also recreation at every moment, to greet the new by reassembling the old, reforming our existences in terms of the new, but from the roots of the old, new/old form, revolution and external return cyclical yet spiral.”

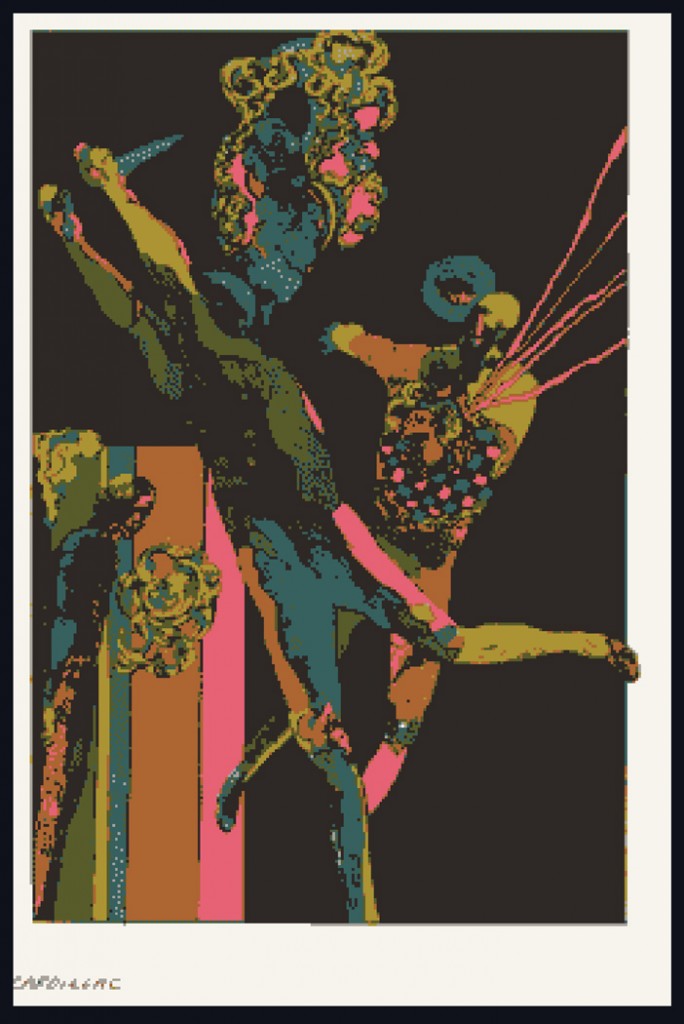

Cadillac

Jacob Landau’s Comments

“Opinions sort out on a bell curve – majority opinions at the apex, minority opinions at the ends. In times of stress, the curve may amplify towards one or the other extreme, but most remain attached to the ambiguous middle.”

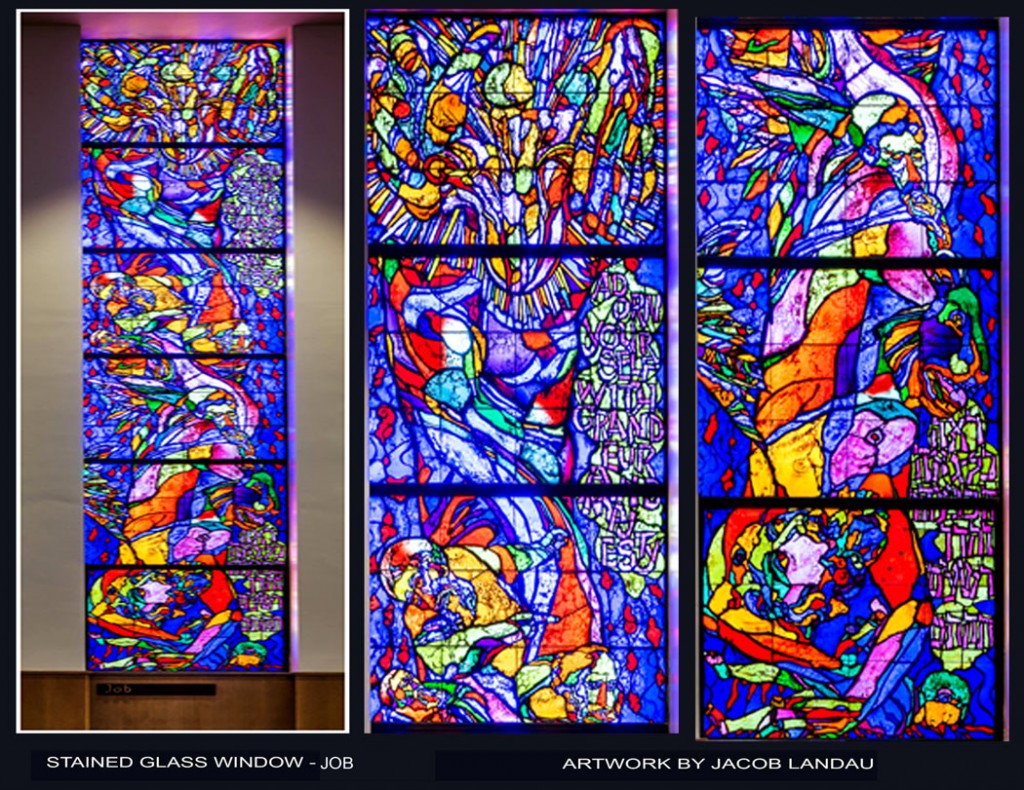

STAINED GLASS WINDOW – JOB

Jacob Landau’s Comments 1999

“When I was young I was attracted to edges of forms rather than volumes. I loved the 16th century engravers, particularly Schongower and Durer. It proved to be too confining and in the sixties I separated the lines from the forms. My work became “painterly”. The quest for the linear, which had begun with an admiration for the comic book with it’s flat colors and it’s defying of gravity, gave way to a play with light and air.

Horse from Animal series

In the seventies I returned to line, but line that is modified by atmosphere. The earlier linear period climaxed with my Dante Lithographs. My figures hovered in a more complex space, involving all of-the elements held in suspension. the works became more sparse, not concerned with sowing off what my hand can do. The climax of this period, interrupted by illness, was reached in the cycle of drawings I did for my wife’s coming down with Alzheimer’s. In these drawings the need to speak directly and without adornments arose. If I can speak directly about my own process at this time, 1999, I hope to complete a group of drawings called Necropolis, to express my horror at the carnage of the 20th century – 130 million killed in all the wars.”

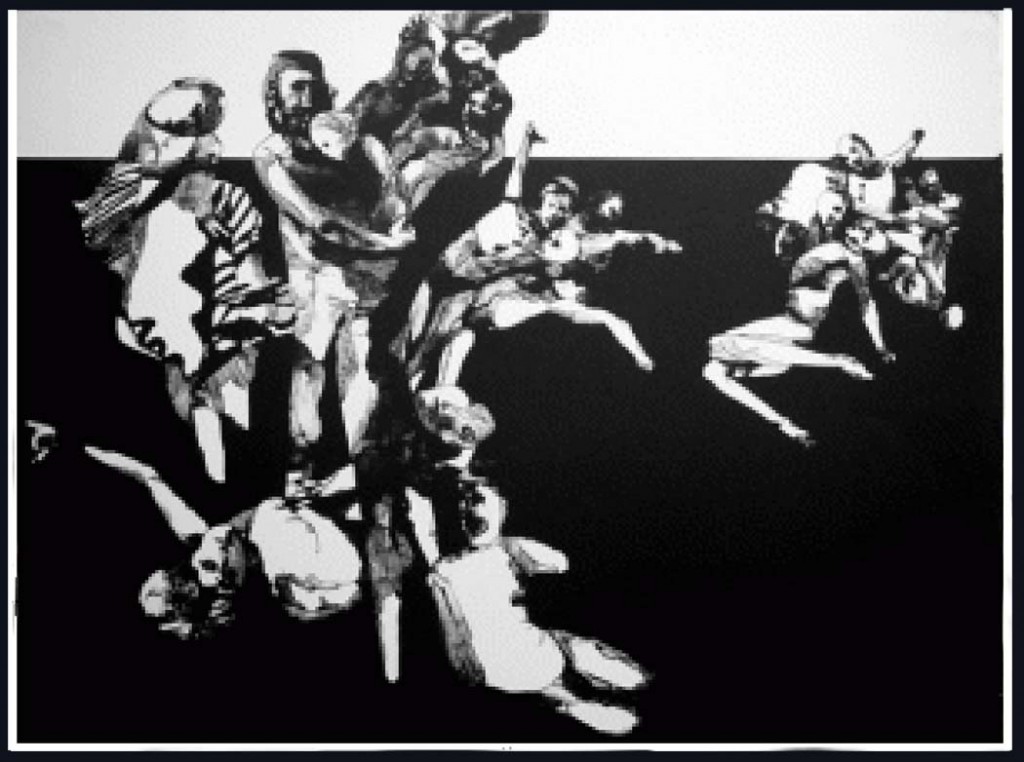

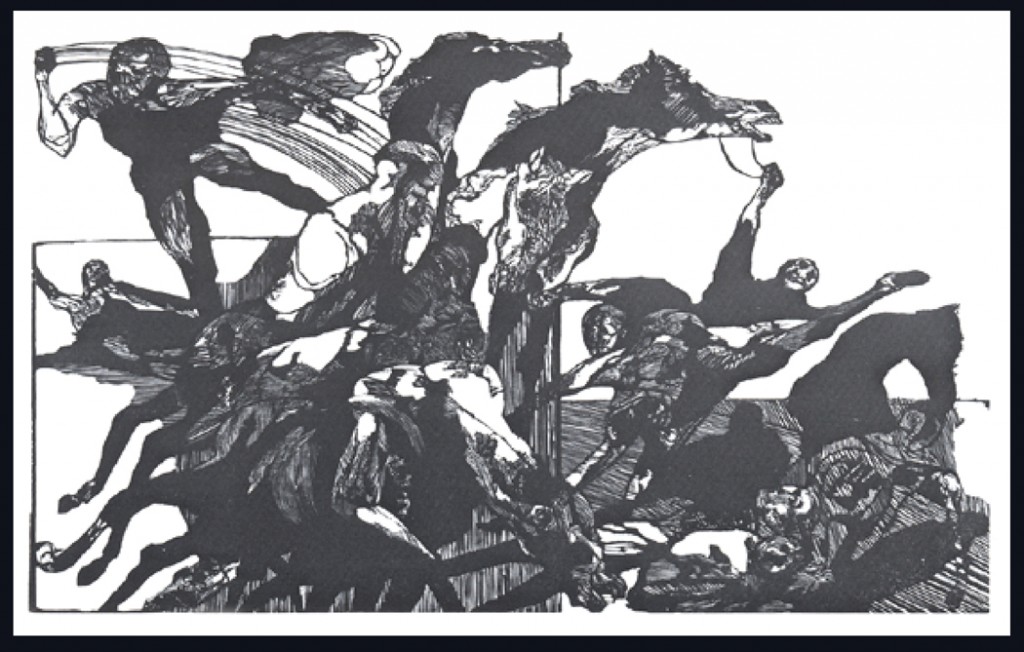

Horses and Men

A VOICE FROM THE PAST SPEAKS TO THE PRESENT ABOUT THE FUTURE

PROPHETIC AND

APOCALYPTIC ART

AN INTERVIEW WITH THE ARTIST JACOB LANDAU … 1978

Fanning: You are a humanist and an apocalyptic artist. In your own words, what does that mean?

Landau: I have a big anxiety about the future. I’ve been involved in Future Studies for quite a long time and the apocalyptic aspect is simply a recognition that the human enterprise is in serious danger. What was, in 1960, when I first got on this kick, definitely a minority point of view, is now very definitely a majority point of view. Among most technicians, technologists, engineers, statesmen, United Nation’s experts and various other futurologists and futurists, practically everyone now concedes that the world is in serious danger. I went to a conference in Texas sponsored by the education section of the World Future Society. A lot of the people there were public school teachers from the West and the whole place looked like Squaresville. I couldn’t believe my eyes! I sit down on the bus next to these innocent-looking women and they’re talking futurism and they’re talking apocalypse and the dangers to the world and I think, boy, if it’s reached them, way out there in the boonies, y’know, it has spread!

In the sixties when I was calling myself an apocalyptist, I gathered a few loyal friends around me. We were, in a way, freaks. You know, there were songs like Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall,” among many that dealt with apocalyptic themes. I remember The Doors saying: “…this is the end, my friend.” The youth of that time were beginning to recognize the handwriting on the wall.

Another famous one during that period was The Quicksilver Messenger Service one called “Pride of Man”- “Oh, God, pride of man, broken in the dust again…can’t you see that flash of fire ten time brighter than the day…” dealing with the atom bomb, and so on. Now, even the heads of corporations know that the system isn’t working.

Peccei, president of the Olivetti Corporation, has formed a group composed of executives of corporations in the European area, called: The Club of Rome. They produced the Limits to Growth study about six years ago (1973) and they have become identified with the struggle to save the world from itself.

Work

Beggs: That’s nice to hear.

Landau: Yes, it’s really exciting to hear that there are a lot of influential people who are beginning to get involved, to work on world problems. Their first study, Limits to Growth, attempted to figure out how much more we could afford to grow economically, and what needs to be done, in economic and political spheres, to cut back on growth in order to avoid catastrophe. The indications are this: that unless certain things are done in a certain order by a certain time, the world system will fail. So, that’s the apocalypse. And, you know, the word apocalypse, in Greek, means revelation; in the last book of the New Testament, “The Revelation of St. John,” which is sometimes called the Apocalypse, the image is one of simultaneous collapse and rebirth or transformation. You must have heard of the famous Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse? One of my students recently declared her belief that “the world will come to an end within the next 15-20 years, that we are in the last period of human history,” that the “Second Coming is at hand.” These beliefs are derived from St. John’s prophecies.

I think it would be inhuman to go on thinking of oneself and one’s career and one’s personal concerns under a situation of international and global emergency. This is not by any means a philosophical point of view that came about as a result of my perception of what’s going on in the world. It’s a philosophical point of view that actually preceded, to a large degree, those perceptions. In other words, I have been a humanist ever since I was a kid, in the sense that I’ve always had a feeling that there are a lot of problems in the world and that I’d like to address myself to them, in one way or another, mostly in my work and not so much in going around with a little collection cup, picking up coins…I mean, that never appealed as a particularly important activity for me. But, I always felt, as an artist, that I wanted to communicate my anxieties and concerns to other people through my art.

STAINED GLASS WINDOW – ISAIAH

Fanning: So was this the kind of feeling that you felt was always with you, no event changed you?

Landau: No, no major revelation took place at any time. I have a book called “Cosmic Consciousness” written at the turn of the century by a man called Bucke, who collected from literature hundreds and hundreds of examples of people whose lives were changed by a sudden revelation, almost like an LSD experience, but in most instances without the help of any external agent like a drug. Something happened to them suddenly to make them aware of their connections with other people, with animals and plants, with the universe, with God. The whole feeling of no longer being a separated ego, but of being part of a larger system of interconnecting linkages. I think I was born with a sense of connection. It’s hard to say why certain people feel that way. I’ve always been inter-disciplinary; I’ve always gone beyond boundaries, any one enclave or territory.

When I went to the New School in ’49 and took five courses, one in sociology, one in history, one in music, one in psychology and one in cultural anthropology, I felt that, instead of writing five separate papers, I wanted to write one, integrated study. I went to each of my instructors and said, “I want to write one paper covering the inter-connections between your subjects.” They agreed. So, you see, as long as I can remember it’s been part of my personality, my dream.

Fanning: Did you think that when you began you art work that you would educate people by reflecting similar attitudes?

Landau: From the beginning, I tended to be didactic. I was an obnoxious kid and I used to think that I had all the answers, that no one else had them. In my youth I was involved with leftist solutions to the world’s problems, with Marxist ideas.

Fanning: You proposed these solutions through your artwork?

Landau: Through my artwork and at that point I also got involved with Young Socialists, Young Communists, Young Radicals. This was during the latter years of my high school experience and the first few years of my time in art school. Later I became disillusioned with radical activism and became more and more interested in developing my art. But, I am proud of what we accomplished. I was involved in organizing, along with others, a cultural workshop in New York City which had a pretty fantastic program. We created art for trade unions and farm cooperatives. We presented shadow plays, puppet shows, elaborate theatre productions, musical events, exhibitions and publications, all dedicated to democratic ideals. We had exciting cultural events on Saturday nights, parties to raise money for the various activities we were engaged in. People like Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly and so many others came ‘round to help us raise money by singing at these affairs.

It was the actual beginning of what later became the folk music craze, long before it was popular. We had a printing press in our headquarters and we turned out leaflets for the Trade Union Movement in New York City. We put out several portfolios of prints which we sold through galleries and dealers, in emulation of the Mexican workshop, the Taller Graficas Populares, a group of radical artists. But, I found, after a few years, that I couldn’t do any of my own work. I was too busy organizing the work of other people.

STAINED GLASS WINDOW – 2ND ISAIAH

Fanning: I guess that’s the classic confrontation for many artists. “Shall I pursue my own work or shall I organize for others?”

Landau: That’s right. Exactly.

Fanning: What was your army experience like?

Landau: Well, I spent three years fighting Fascism from a desk… actually behind a bottle of booze. I was bartender for my outfit. This was in Italy. My commanding officer asked me to run an enlisted man’s club for the ‘boys.’ Then I became involved with Special Services where I edited a magazine, wrote and illustrated articles, took photographs, did layouts and so on.

Fanning: So by editing you became familiar with words.

Landau: Yes, I’m a word man, too. I’m an omnivorous reader. I have an almost photographic memory for correct spelling. I love communication through language.

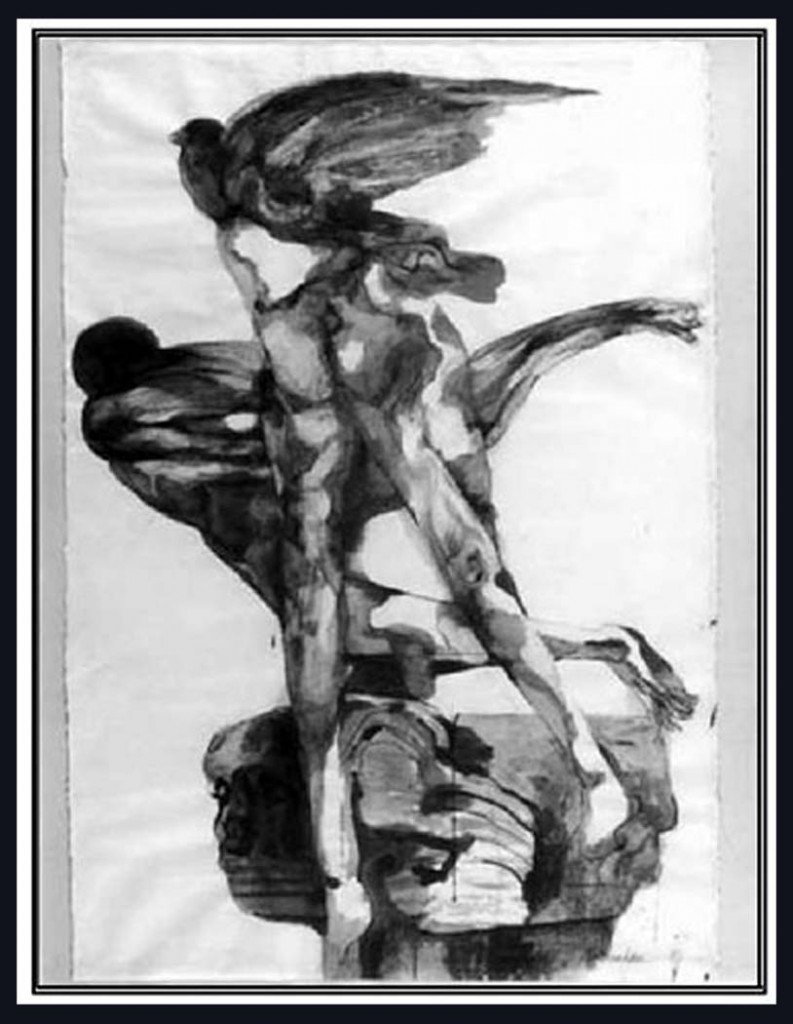

Modern Prometheus

Modern Prometheus

Fanning: Most artists I know say they have a difficult time relating to the written word.

Landau: Don’t always believe that that’s true, A lot of artists ‘pretend’ that they don’t relate to the written word but they do. It’s a pose, in many instances. It’s part of the tendency toward specialization in our time. You know, a visual artist is supposed to be purely ‘visual’ so he’s not supposed to be a writer or have verbal aspirations. They go around, ‘Duh-duh-duh-duh,’ acting like they can’t say ‘nuttin.’ But, ask them to write a statement about their own art and it often turns out to be most erudite.

Fanning: What else were you doing in the Army?

Landau: Well, I was editing and doing photography work. It was fun, because I was asked to travel around Italy to visit different outfits and find out what they were doing in Special Services activities. I was only a corporal but everywhere I went I was taken for a spy from headquarters. So, the officers wined me and dined me, and I would go into my moral act: “I cannot accept this case of whiskey because it might be interpreted as a bribe.” While I was in Italy, three friends and I decided we were going to Rome, which at that time was OFF-LIMITS, to see the Vatican and the Sistine Chapel, because, you know, nobody in the Army ever knew how long he would be stationed in one place. We were afraid we’d move somewhere and miss our chance.

So, we took a weapons carrier, which was authorized for recreational purposes, to Rome, which we definitely were not authorized to do! An Italian civilian, who worked on our base, claimed that he was a cousin to the Pope’s secretary and said he could get us into the Vatican. We weren’t allowed to transport Italian civilians in military vehicles so we dressed him up in a soldier’s uniform. This was an even more heinous offense! We were driving along, bleary-eyed, tired, and all of a sudden there was the Coliseum! We stopped, went into the Coliseum, and the driver of the vehicle took off the distributor cap just to make sure nobody stole the vehicle. We come out, sure enough, the vehicle’s gone! So, as we’re sitting around trying to figure out what to do next, we see, at the next corner, our weapons carriers being towed by a military police tow-truck. For blocks we chase this vehicle as it moves through Italian traffic. We finally trace it to the military pound-where they impound unauthorized vehicles. Of course, we claim our truck, and of course, they find out about the civilian who isn’t a soldier, and they type a full report to our commanding officer, and then they give us back our vehicle, and it’s only 10:30 in the morning so we say; “Onward to the Vatican!”

Beggs: You were in trouble already.

Landau: Sure, what did we have to lose? So, we went to the Vatican and, sure enough, this guy turns out to be a cousin to the Pope’s secretary and he got us in. We were attached to a group of pilgrims who were on their way to an audience with the Pope. And we were all blessed and we saw the Sistine Chapel. It was an ideal circumstance because there were only 25 people in the group. We were given a guided tour through the Vatican Museum and went home feeling very happy only to discover that we had all been ‘Reduced in Grade.’ In my own case, from corporal to private first class!

STAINED GLASS WINDOW – AMOS

Fanning: Have you been back to Italy?

Landau: Several times. I LOVE that country. It’s a great country and the Italians are such marvelous people. They know how to live, they are more relaxed. My wife and I went into a fruit and vegetable store at noon and the guy said: “Sorry, closed, can’t sell you anything now.” So, we come back later thinking we could buy bananas we wanted and found it was still closed… strange. So, we drop by the following morning and I ask the owner in what little Italian I can muster: “How come you were closed yesterday in the afternoon?” He said, “Well, I made enough money in the morning so I went fishing.” That’s pretty terrific, isn’t it? It’s so much more human.

Fanning: How did you become involved in the type of work you’re doing now?

Landau: It was a long, hard climb. At first I developed a portfolio, took it around. I’d pick up freelance jobs here and there. I had an agent. I was really interested in spending my time painting but I didn’t have the wherewithal to do it. In 1949 I married Fran and we decided to go off to Europe on the G.I. Bill which offered me at the time, five years of education, including a living stipend. I began to do woodcuts in Europe and on my return was commissioned by many publishers to do large numbers of prints.

Fanning: How were you keeping up with your original ideas while you were freelancing?

Landau: I kept doing drawings that were going to head toward paintings that I didn’t have to time complete during that period. It was all very frustrating. I became very ill during that period. I was very stressed because I wasn’t doing what I wanted to do… I’ve written an article discussing the problems of the artist, what is needed to help out the artist and how other countries have gone a lot further in this direction that our country has. I quote Agnes de Mille’s statement to the effect that in Europe, for hundreds of years nobody expected the arts to pay for themselves. For some reason or other in America we have that expectation. We give artists a grant for one year, assuming that this one year will pull them forward, out of the pits far enough so that they can make it on their own. In the main, that’s bull! The National Endowment of the Arts conducted a survey and found that the average artist’s income ranges between $4 and $8,000 a year. This figure includes income derived from other jobs; if you strip away the average it’s about four thousand bucks a year from the sale of one’s art work, a miserable pittance. We’re talking about the fine arts, of course, commercial artists make out a lot better.

Fanning: What is the situation as far as government taxation of the artist is concerned?

Landau: How they screw us up, you mean?

Beggs: As an example, should I buy a piece of Jacob’s work and submit it was a gift, I get a full tax deduction, but if Jacob, as the artist, submits a piece of work to be accepted by a museum, he can only deduct the cost of materials.

Landau: There’s another part to that. The moment I die, everything in my studio becomes taxed at the full market value! In the instant after my death, my work suddenly becomes that much more valuable to the I.R.S. I can’t judge what all the rationalizations were because I didn’t follow the arguments on the parts of the senators and the congressmen who were voting on these tax laws, but my guess is that they represent, in part, a punitive action against the artist. Because a lot of artists were generally counted as liberals and these congressmen don’t like liberals. They were just trying to get even with them.

Canada spends four times as much as we do, on a per capita basis, for the arts. They’re a much poorer country, of course. Most European countries support the arts more generously than we do. Even at that, it’s still lousy for the artist in many parts of the world.

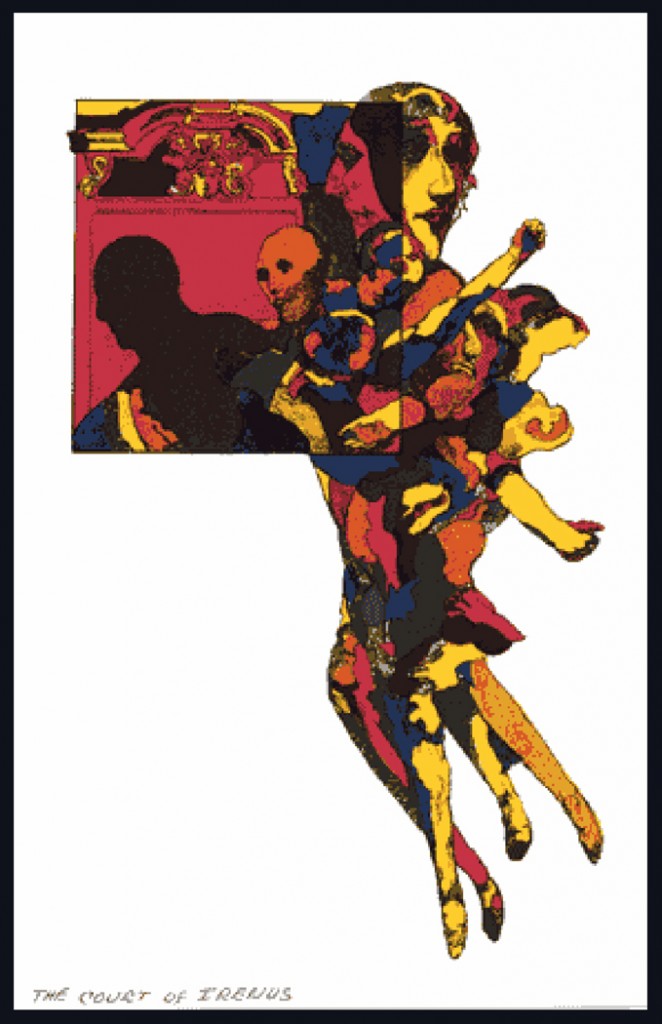

The Court of Irenus

The Court of Irenus

Fanning: Why do you think the American government would choose to thwart a segment of society whose goals are to create a better life?

Landau: The arts are considered luxury items, they’re not considered necessities. Most people are not aware that the arts are just as important as the sciences. Art humanizes us; it makes us more aware of our relationships with the universe, with ourselves, with other human beings. If we don’t have these connections, we turn into monsters; we become one-sided creatures, automata. That’s what’s happening on a global scale. People are becoming more and more “pragmatic,” more willing to put up with inhuman conditions, turning more and more into machine-like creatures. Kids are being taught in school how to learn facts and how to regurgitate facts. They’re not being taught how to relate or interact with each other. Nobody can measure creativity, the art “sense” or art side, so it isn’t taught, it isn’t encouraged. We teach only what we can measure. But interacting with other people is part of the art side of the personality. Being able to show love for other people is part of the art side. Being creative in any direction, not just in the visual arts, is part of the art side. But schools don’t encourage that creativity except within narrow, controlled limits. If you work for a boss and you’re creative for that boss, that’s okay. You stay within the boundaries that are set up for you. But if you get creative to the point of asking: ‘Is this business necessary?’ ‘Does this business cause public injury?’ …you run serious risks. Your creativity is “out of bounds.”

Fanning: Do you feel that people in society have turned into machine-like personalities because they are afraid to confront what their society has become?

Landau: Yes. I think the artist is the only role model in our society that still retains a measure of humanity. The vast majority of people have lost theirs, have become dehumanized, and this is by no means an attack on everybody else, on the contrary, it is an attempt to support what’s left of their humanity by pointing out what’s been surrendered or lost. The only reason the artist retains it is that the artist has a tradition of self-actualization, of being preoccupied with the beautiful, and the exploratory, and the experimental, and the creative, and the questioning and the cosmic. The rest of the world is all fragmented and splintered and mechanized and turned into cogs in the machine, or rather ‘wires in the circuit.’

STAINED GLASS WINDOW – MALACHI

Fanning: What would you see as a solution for education?

Landau: The only solution for education is to move toward a “Limits to Growth” concept, toward these non-traditional forms, in my opinion, toward small, human scale operations with learning segments that are not organized around semesters or years. If you want to learn how to do video and it can be taught in five days, do it. If you want to learn how to be a waitress and if you think it can be taught in a weekend, you can do it. Whatever! If you want to be an artist and you want to learn how to draw, then you should be able to take three weeks of solid drawing and then go off on an independent study binge and do a whole lot of drawing on your own. And then come back for another high density stint, a recharging of the batteries. This is the way, I’m sure; it’s going to be in the future.

Fanning: Why do you think the structure of our educational system has no evolved toward an independent/non-structured environment?

Landau: It’s obvious that one of the reasons for this is that we live in a society that has to bureaucratize everything. That has to try to set up what they consider to be standards of admission to the club. Whatever club you want to join, you have to get the right credentials, and they have to start measuring everything that goes into it. They have to figure out what it is you’re going to be measured on in order to make it possible for you to enter the club, to get the credentials that will admit you to the club. Once you begin to move in that direction, you end up by setting up huge, fantastic structures that teach everything but the right things.

I’m not saying that the things they’re teaching toward being a doctor or a lawyer are always the wrong things but they are so highly specialized in their tendencies that they simply perpetuate the problems of our society because the medical doctor loses contact with the human values involved and become a money-making machine. Lawyers also lose contact with human values. They each don’t know very much about the other, about each other’s disciplines, and everybody’s fragmented. That’s partly why the world’s in the mess that it is.

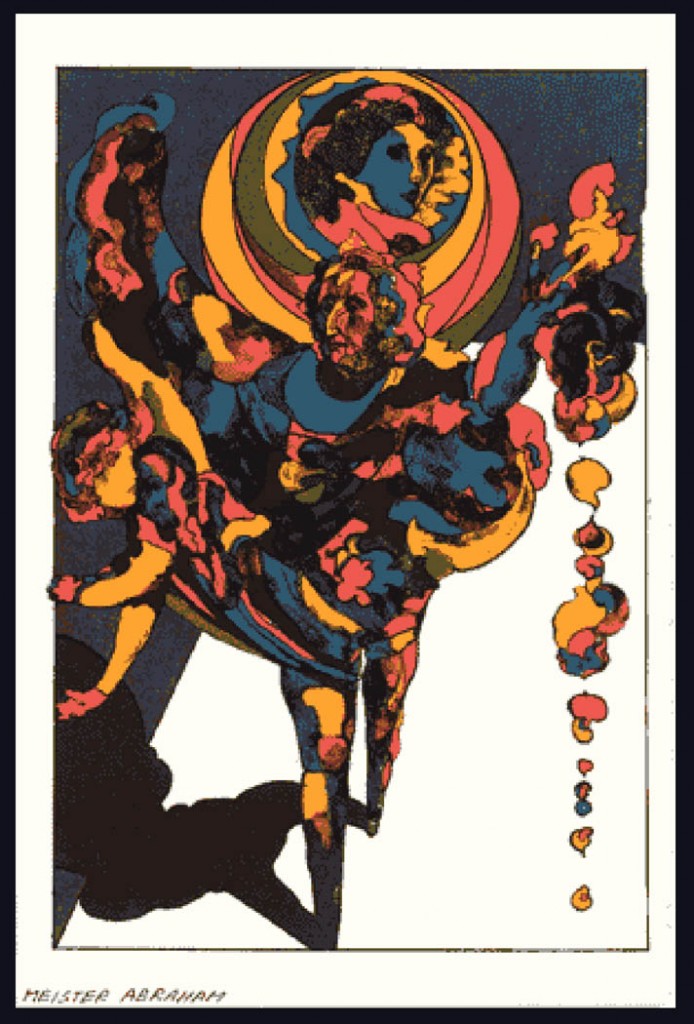

Meister Abraham

Meister Abraham

Fanning: How does your humanism get translated into a piece of art?

Landau: First of all, there is a tradition that I relate to. Oddly enough in our art schools, generally, and in the art establishment particularly, there’s a very big worship of the French tradition, the French Modern tradition: Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso and all the rest. When I went to art school, I became, as did everybody, very enamored of Picasso and all the other French artists. At the same time, I had a hard time trying to assimilate them into my own work. I felt that the influences were somehow wrong for me, and I couldn’t figure what it was all about. Simultaneously, with that, I was also very much interested in and influenced by some of the Mexican artists like Orosco and some of the European artists like Beckmann and Grosz. Because the pressure on the part of the schools and the establishment was all in favor of the French tradition, I began to feel guilty that I wasn’t falling for these guys whereas everybody else was. It took me quite a number of years to realize that the German tradition was really my tradition, not the French.

The German tradition and the North European tradition, generally, is much more visionary, romantic, utopian, social-critical, social-humanist, or whatever you want to call it, whereas, the French tradition is much more involved with beauty and sensibility, and the object as an object and the aesthetic aspect of art for art’s sake. I never could go for an art for art’s sake aesthetic. So, in a sense, as an important aspect of my development as an artist, I was beginning to recognize where my artistic roots were, which turned out to be elsewhere than in the French tradition. My work, from the beginning, was to take on an expressionist rather than an impressionist, or post-impressionist or formalist flavor.

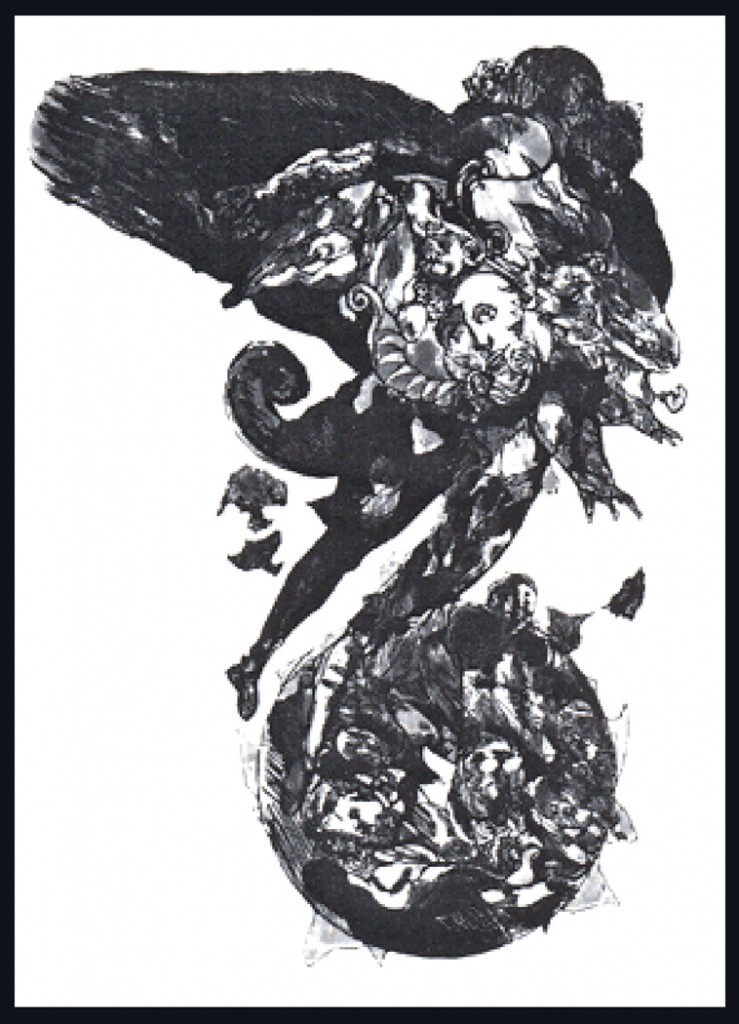

I never quite got into political art because that seemed to me to be more closely associated with journalism. I wasn’t into journalistic art. The general, more social, critical aspect was very interesting to me in the ‘30’s and the ‘40’s. I used to do paintings about unemployed people and unfortunates of the world and concentration camps in Germany. And, later I think I became more involved with something that was implicit in my work but had not yet surfaced and that is a vein of personal fantasy; tapping into a dream world or visionary world.

Fanning: Were these fantasies on how ‘you’ would like the world to be?

Landau: Maybe, but it also has to do with just sheer personal and archetypal fantasy in its own right… sort of working much more with the subconscious, and with the impulses, with the feelings rather than with conscious efforts to teach a lesson. In other words, it was like moving away from didactic, you know, in my earlier years I was an obnoxiously didactic person. I was going around telling everyone what to do and how to do it. After awhile, I moved away from that. I began to realize that there were a lot of things wrong with what I was trying to tell other people about; especially when I began to find that I no longer believed in some of them. That we are all fallible human beings. That no one of us has an final answers and that we’re all explorers in a world full of uncertainty.

I did a suite of lithographs called Charades… I associated the name Charades with what Goya had called Caprichos, …riddles, puzzles. He also did a series called Proverbs, where he picked up on sayings that were common in the land, but dealt with them in mysterious, puzzling ways. And, I dealt with what came out of my obsessions, things that I did not fully understand. Fear o death, for instance, and a sort of frustrated feeling of love. These are obsessions that manifest themselves in various ways and images. The reason they seem to appeal to others is because apparently other people share some of the same obsessions. That’s where the archetypal aspect comes in.

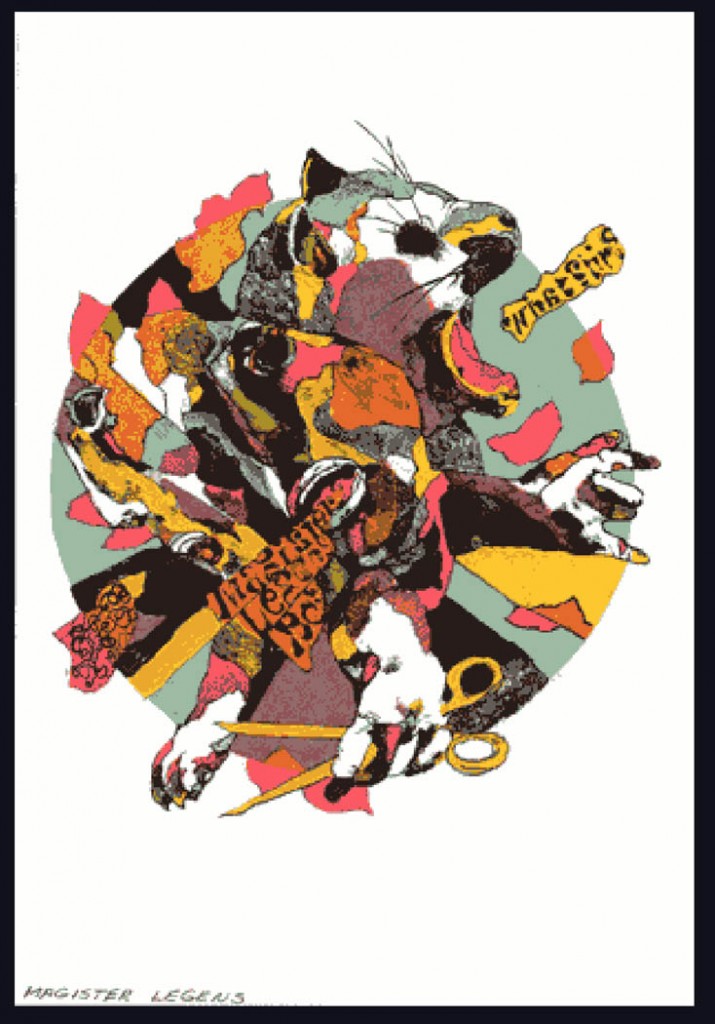

Magister Legen

Magister Legen

Fanning: Is this a constant… this overflow of ideas?

Landau: I’ve got tons of things on my mind that I’ll probably never realize in my lifetime, that I would love to do and can’t because there just isn’t enough time to do them. Anyhow, I liked lithography (because it is faster than woodcutting) but it has other problems. One of the problems is that unless you want to take the time to do your own printing, you have to have a lot of money to pay a professional printer to do your editions for you.

During the latter part of the ‘60’s it was possible to get print dealers to subsidize the printing of various editions. Now, it’s a good deal more difficult because the market has fallen off for “serious” lithography, whereas there is a much bigger market for decorator art, great, big, brassy, colorful prints that match the sofa. Not the sort of art that I’m particularly interested in.

KREISLER

KREISLER

Fanning: Is there a difference to you between your prints and projects such as the stained glass windows which may or may no have staying power? (10 stained glass windows Landau designed for the Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel in Philadelphia; 24 ft. tall and 5 ft. wide dealing with the prophets of the Old Testament with whom he had said he strongly identified.)

Landau: Prints that are stored in museums or cared for in homes will last as long as the windows will. But the windows represent a public work of art, to be seen daily by many people, unlike painting and prints which are primarily designed for private consumption. Artists, all of us, in fact, are concerned in one way or another about immortality. Becker wrote a beautiful book called The Denial of Death, which is a study how all of us throughout history have tried to dent the fact that we die. We construct, not only religions, but various other activities, wars and violence of one kind or another as ways of overcoming our fear of dying. It’s an odd paradox. The way we do it is to attach ourselves to some hero figure or some hero myth, and the hero figure or myth requires us in some way to kill other people or sanction their deaths so we may achieve our own immortality through identification with the hero, the ideology, the dream.

As Becker puts it; “Better you should die than I.” In a way, one of the immortality myths that drives the artist is the feeling that whatever he or she turns out will outlast him or her, that it will be a voice speaking for future generations.

Fanning: Do you think this quest for immortality is a preoccupation?

Landau: Though they may not think about it consciously, a lot of artists feel it very strongly. Beethoven, for example, was a very popular composer during a good part of his life but many pieces he wrote were misunderstood, and were not performed widely. He remarked on several occasions: “Future generations will understand this.” If the Impressionist painters of the 19th century had relied exclusively on the renown they achieved during their lifetimes, they would have had very little satisfaction. But they were sustained by a deep belief that what they were doing was in the long run important, even though in the short run, it failed to be recognized or appreciated.

Fanning: Would that seem to be the only reason an artist would attempt a work of art?

Landau: It would be one reason, not the only reason. The obsessive aspect is an important reason, too. An artist has to be an artist for some internal reasons that have to do with the need to express something, to externalize some kind of vision, or dream, or anxiety or whatever it is that is deeply rooted. Also, artists are moved by a very deep and strong and abiding need to communicate with other human beings in some way; to share themselves.

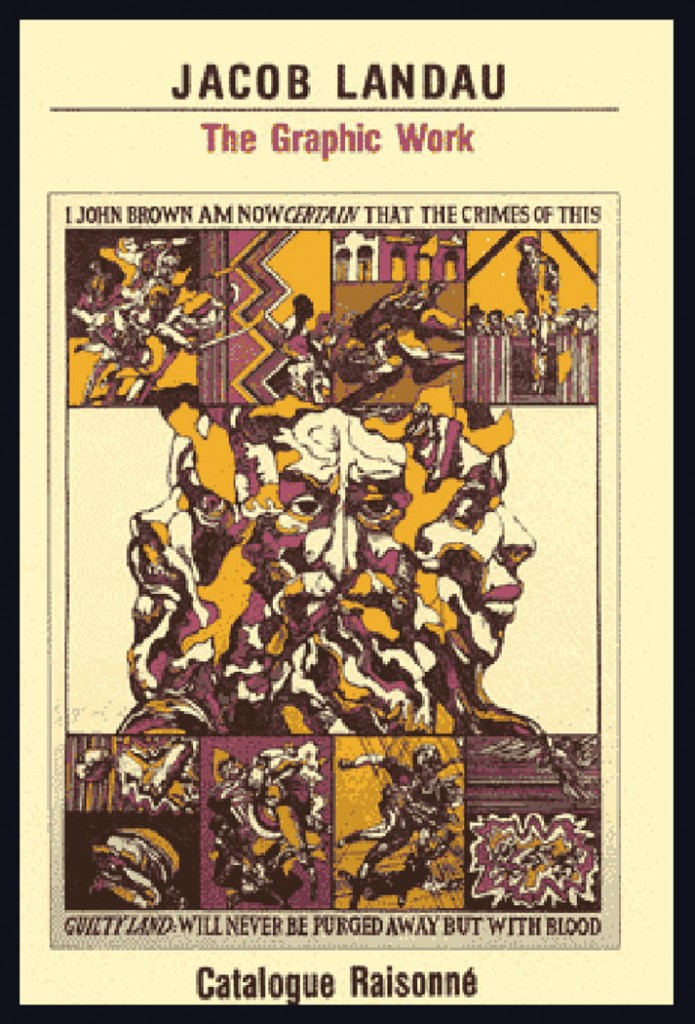

John Brown

John Brown

Fanning: How about creative blocks?

Landau: Sure, you go through periods where you’re more creative than others. There’s no doubt about that. Most artists cover up for their blocks or hang ups. The only way they can maintain a professional presence in the media environment is by pretending to be more together than they really are which means there’s a need not to admit they’re human. I refer to the media environment that Marshall McLuhan (The Media is the Massage) talked about. It’s a posture, a pose, on camera so to speak, that they have to strike in order to sound as if they’re got it all together all the time that everything is always working out for them. If they do admit to some problems of difficulties, they do it in a very calculated way to make themselves sound a little more human, not necessarily to reveal anything that might undermine that image, the way in which most artists and public figures behave. It’s also part of our educational system, too. We have a tendency to think that when one graduates that he or she is a “finished product.” And, artists, once they’ve “arrived,” also act as if they’re finished products. Although artists will pretend that they’re still growing, involved in process, the actual truth of the matter is many of them do not continue to change once they’ve “arrive.” This, because their clients demand that their work remain essentially fixed at a certain stage because that’s what they’re accustomed to seeing, because the critics, curators and collectors have made an investment in that particular image and they want to hold onto it. I suppose I have as much need as anybody else to play that professional role up to a certain point. Nevertheless, I am inclined to be much more revealing about my own true feelings about things, because I don’t believe in hiding what I am as a person; my work is, in any case, a dead giveaway of who or what I am.

I have my share of paranoia like everybody else in this society, which is partly what I’m talking about. The paranoia urges us to “watch out for the next guy,” and to not reveal any more than we have to about ourselves unless we are in a bar with a couple of other drunks in which case we can talk our heads off and nobody will remember. That’s part of the folklore of American life; that American men, particularly businessmen, will talk to strangers about the most embarrassingly intimate things, things that they wouldn’t even tell their own therapists.

While I have my share of the common paranoia, I guess I have a good deal more trust in other people than many people I know. It tended sometimes to work against me in the sense that I frequently vested trust in people that didn’t deserve it and I got hurt in the process. I would think, each time, that I had learned not to do it again, and then I would go ahead and be trustful the next time, just the same way, all over again.

Fanning: I think you can trace that back to those human qualities?

Fanning: I think you can trace that back to those human qualities?

Landau: Yes, I can’t help it. I am not personally-designed; my structure doesn’t allow me to turn into a machine-like, paranoiac, manipulating, controlling personality. I just can’t be that way.

Fanning: What does the new series of drawings you’re working on deal with?

Landau: The starting point is the cross image from The Revelation of St. John. In a way, the first part of the series will be dealing with the difficulties the modern world faces as it moves toward what some have called “The Transformation,” from a competitive, exploitative, destructive, manipulative society to utopia or oblivion, in Bucky Fuller’s words: to a more humane society or toward catastrophe.

Fanning: How do you spread the word about yourself or do you bother?

Landau: I don’t bother. No, I’ve been relying essentially on galleries to represent me.

Fanning: Do most artists feel this type of pressure to produce these one-person shows?

Landau: I don’t think that they acknowledge it but they do feel it. Artists will often pretend that they don’t have any problem with it.

Beggs: It’s like your new fall line.

Landau: Yes… most are so completely integrated into the dealer/client/critic/gallery system that they no longer question its value. They accept all the terms under which they are obliged to operate. Many of them are willing to work with galleries that are absolute horrors. I’m talking from the point of view of their human relations, from the fact that they often don’t pay the artist and that they subsidize their operations on the basis of unpaid obligations. Artists are willing to put up with it as long as they have a showcase on the “Avenue” so they can get some critical attention. I think this is part of the corruption that the artist feels he or she must put up with-what a shame!

Fanning: Just to have their work shown…

Landau: Right. I’m fortunate in a way, that I’ve gotten to the point in my work where I don’t have to feel that pressure. I sell enough to prove a decent income. I also teach. I don’t need to become rich. So, between these conditions, I’m more or less able to do what I want to. And I want to go on exploring the human condition.

45 East Main street, Holmdel, NJ 07733

Sat. 12pm – 4pm weekend & evening by appointment • 732 993 5278 or 732 993 5ART

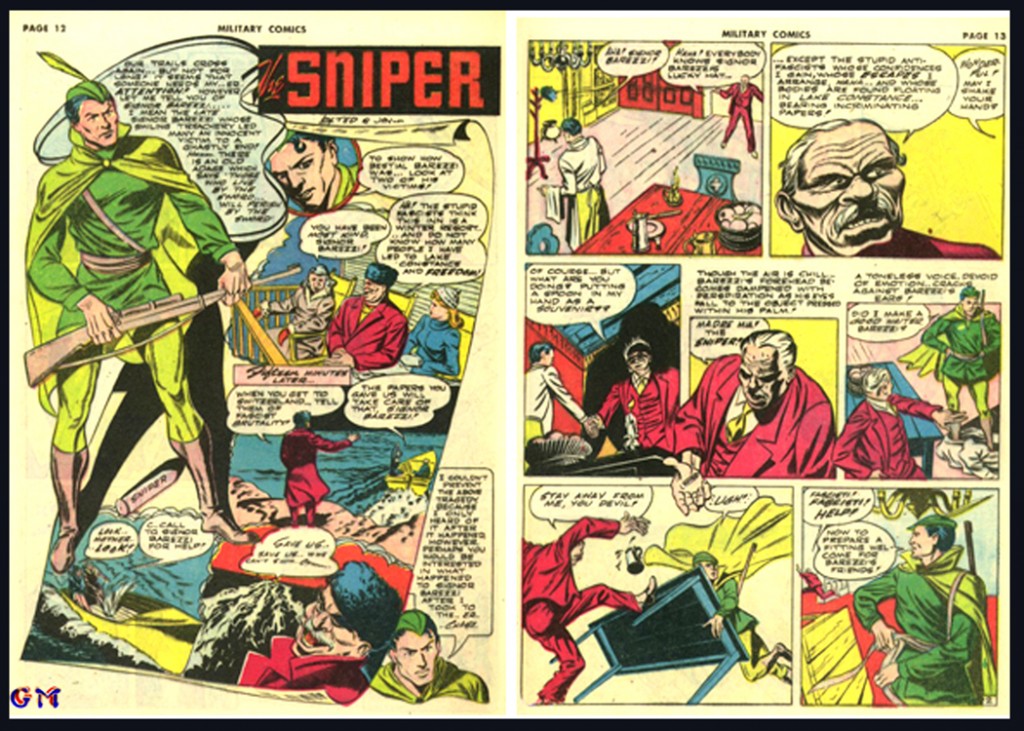

Posted By 13th Dimension on Apr 6, 2014

Tom Chesek on artist Jacob Landau’s career in comics and fine art.

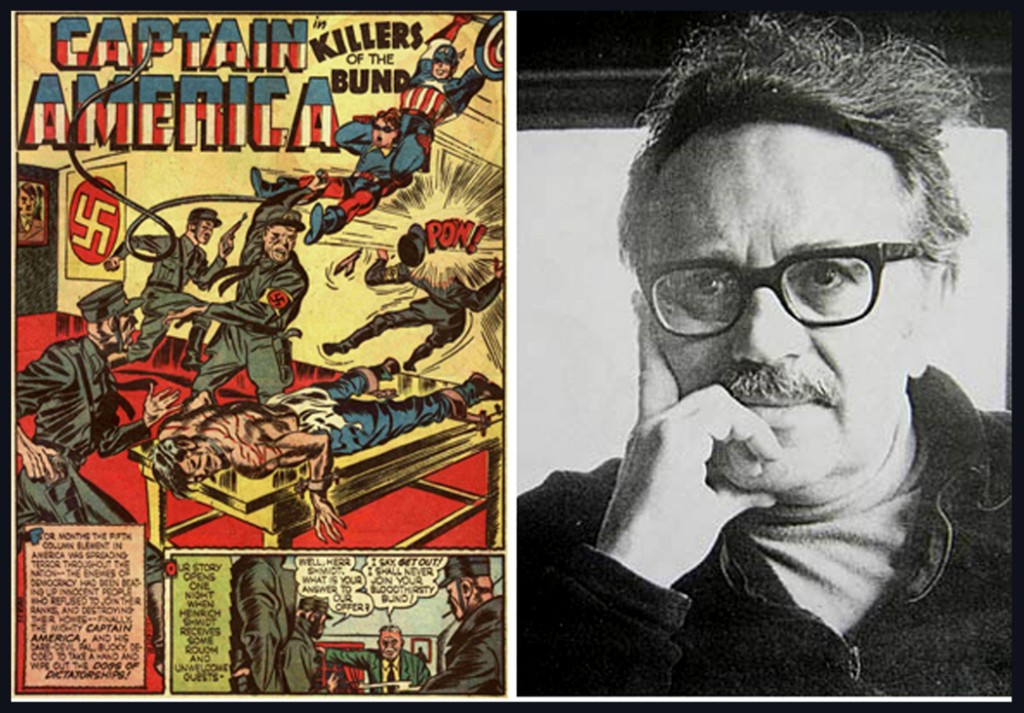

The forgotten Quality Comics hero THE SNIPER stands as a Golden Age feather in the cap of Jacob “Jay” Landau, in the decades before he became a noted educator, illustrator and fine art printmaker. A retrospective of Landau’s war-themed work is on display at NJ’s Monmouth University, April 10 through 24, 2014.

The late Jacob Landau is pictured with one of the Simon-Kirby studio CAPTAIN AMERICA stories that he likely worked upon.

The late Jacob Landau is pictured with one of the Simon-Kirby studio CAPTAIN AMERICA stories that he likely worked upon.

Collections of Landau’s Work[edit]

The Jacob Landau Institute was founded to preserve the memory and legacy of Jacob Landau. The Institute has established two major cooperative agreements to this end. Drew University Library permanently houses the Jacob Landau Archive, which includes his papers, artwork, and books. The Library is currently working to organize and preserve the materials in the Archive for the use and longevity of Landau’s legacy. The Jacob Landau Institute works in conjunction with Monmouth University inWest Long Branch, New Jersey to create educational programs that have far reaching benefits for the artistic community and general population of Monmouth Countyand beyond.

Ing’s comments on Jacob Landau artist and teacher

One night after I finished school homework, I went to bed but I could not sleep. I sat by my bedroom window looking at the bright full moon in the sky. Wondering and thinking about what I want to be when I grow up.

I would like to be a doctor, and then I can take care of people.

I wished I would live in a small village taking care of everyone in the town, seeing people happy, healthy and strong, with loving and kind heats to everyone.

No one would be starving because our farmers would cultivate crops so well.

I was day dreaming at night while the moon was moving to remind me that it was late night. I must go to sleep because tomorrow will be my final exam for fourth grade. I will be older and move up to fifth grade next year.

That was a long time ago in a small village in the middle plain of Thailand when I was about twelve years old. Now I am old and I am not a doctor but people can call me an artist. Even though I cannot take care of sick people I still have the same wish to help the mankind. I wish no one to suffer. We can all helping to take care of each others’ well-being. But it is only wishful thinking when they are so many homeless people everywhere and people are suffering from wars around the world.

When I studied Mr. Jacob Landau’s biography I found that some of his comments are similar to my way of thinking, such as:

“Thou shalt not kill”, we say, except when authorized by the state. And so the slaughter goes on, one hundred million in this century alone, and still counting. And death is not enough. We humans are the only creatures on earth who practice torture.”

“Art is re-creation, a second coming, resurrection of past life, of things dead and gone. Creative living is also recreation at every moment, to greet the new by reassembling the old, reforming our existences in terms of the new, but from the roots of the old, new/old form, revolution and external return cyclical yet spiral.”

Fanning: Do you feel that people in society have turned into machine-like personalities because they are afraid to confront what their society has become?

Landau: Yes. I think the artist is the only role model in our society that still retains a measure of humanity. The vast majority of people have lost theirs, have become dehumanized, and this is by no means an attack on everybody else, on the contrary, it is an attempt to support what’s left of their humanity by pointing out what’s been surrendered or lost. The only reason the artist retains it is that the artist has a tradition of self-actualization, of being preoccupied with the beautiful, and the exploratory, and the experimental, and the creative, and the questioning and the cosmic. The rest of the world is all fragmented and splintered and mechanized and turned into cogs in the machine, or rather ‘wires in the circuit.’

Fanning: Why do you think the structure of our educational system has no evolved toward an independent/non-structured environment?

Landau: It’s obvious that one of the reasons for this is that we live in a society that has to bureaucratize everything. That has to try to set up what they consider to be standards of admission to the club. Whatever club you want to join, you have to get the right credentials, and they have to start measuring everything that goes into it. They have to figure out what it is you’re going to be measured on in order to make it possible for you to enter the club, to get the credentials that will admit you to the club. Once you begin to move in that direction, you end up by setting up huge, fantastic structures that teach everything but the right things.

I’m not saying that the things they’re teaching toward being a doctor or a lawyer are always the wrong things but they are so highly specialized in their tendencies that they simply perpetuate the problems of our society because the medical doctor loses contact with the human values involved and become a money-making machine. Lawyers also lose contact with human values. They each don’t know very much about the other, about each other’s disciplines, and everybody’s fragmented. That’s partly why the world’s in the mess that it is.

Fanning: Would that seem to be the only reason an artist would attempt a work of art?

Landau: It would be one reason, not the only reason. The obsessive aspect is an important reason, too. An artist has to be an artist for some internal reasons that have to do with the need to express something, to externalize some kind of vision, or dream, or anxiety or whatever it is that is deeply rooted. Also, artists are moved by a very deep and strong and abiding need to communicate with other human beings in some way; to share themselves.

Fanning: Just to have their work shown…

Landau: Right. I’m fortunate in a way, that I’ve gotten to the point in my work where I don’t have to feel that pressure. I sell enough to prove a decent income. I also teach. I don’t need to become rich. So, between these conditions, I’m more or less able to do what I want to. And I want to go on exploring the human condition.

I learned a lot from Mr. Jacob Landau’s philosophies and his artwork. His artwork show’s us a period of turmoil in history. He deeply felt the horror of the event such as The Holocaust which he translated and expressed in his art form. I too am deeply affected by the war that is going on at the present time. Genocide happened and was called, The Holocaust. But it also happened before this event, and it is still happening now, especially in Syria and some countries in Africa. It seems like we humans never learn from the past. But we can manage to learn how to produce better weapons that can be more efficient and kill more people. “Thou shalt not kill, we say, except when authorized by the state. And so the slaughter goes on ——–“

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Monday, May 3, 2016

Thanks to all the websites and Institutions that recorded Jacob Landau’s artwork and his activities.

For more information please visit the following links:

https://www.monmouth.edu/jewish_cultural_studies/jacoblandau.asp

https://www.jacoblandau.org/jacoblandauinstitute.htmlr s

https://www.jamesyarosh.com/jacob070409_3.html

https://www.drew.edu/library/special-collections/listing/landau-archive

https://13thdimension.com/jacob-landau-a-fine-artists-cap-and-kirby-connection/

https://judithestein.com/jacob-landau-old-man-mad-about-drawing

https://www.willethauser.com/jacob-landau

Leave a Reply