Remember Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Black Astronauts, Ed Dwight, Sculptor, A Black Midwife

Monday, January 20, 2025

Ing’s comments:

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Monday, January 20, 2025

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts’ Artwork, PBS News, Wikipedia, Legislative Reference Library of Texas, Texas African American History Memorial, A sculptor Ed Dwight, ABC News

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. – Human Rights and Nonviolence

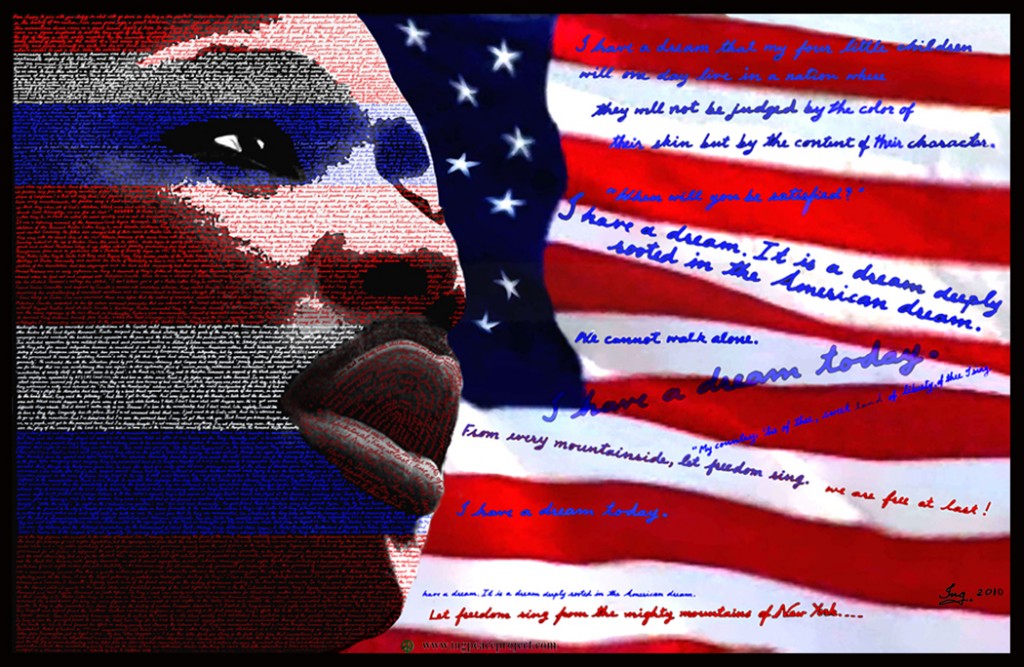

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “I Have A Dream”

Artwork by Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts

Remember Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. – Human Rights and Nonviolence

I did this artwork in 2010. I enjoyed doing the research, reading Dr. King’s biography and his speeches. Dr. King was a great writer and orator. He could captivate the audiences with his great writing and presentation. I would like everyone who views my artwork on Dr. King to be able to read and have some understanding of his feelings. With his wit and energy, he devoted himself to human rights and nonviolence. It is not only his family that lost and mourned his death for the world has lost a great man. Humanity had lost Dr. King’s ability to help bring progress to the world by achieving more civilized interaction for the human race as a whole.

‘The Space Race’ documentary explores Black astronauts’ efforts to overcome injustice

PBS is an American public broadcast service.

Feb 12, 2024

A new documentary explores the little-known stories of the first Black pilots and engineers who were pioneers of NASA’s space program. Geoff Bennett has this look at the film, “The Space Race,” which airs on the National Geographic Channel and is streaming on Disney+ and Hulu. It’s part of our arts and culture series, CANVAS. Stream your PBS favorites with the PBS app: https://to.pbs.org/2Jb8twG Find more from PBS NewsHour at https://www.pbs.org/newshour Subscribe to our YouTube channel: https://bit.ly/2HfsCD6 Follow us: TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@pbsnews Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/newshour Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/newshour Facebook: http://www.pbs.org/newshour Subscribe: PBS NewsHour podcasts: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/podcasts Newsletters: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/subscribe

Transcript

New National Geographic documentary tells the real-life story of the first Black astronauts

16M subscribers

2,818 views Feb 14, 2024 #abcnews #blackhistory #space

@NatGeo‘s documentary “The Space Race” features the real-life story of the first Black astronauts. Subscribe to ABC News on YouTube: https://abcnews.visitlink.me/59aJ1G Watch 24/7 coverage of breaking news and live events on ABC News Live: ![]() • LIVE: Latest News Headlines and Event… Watch full episodes of World News Tonight with David Muir here:

• LIVE: Latest News Headlines and Event… Watch full episodes of World News Tonight with David Muir here: ![]() • ABC World News Tonight with David Mui… Read ABC News reports online: http://abcnews.go.com ABC News Digital is your daily source of breaking national and world news, exclusive interviews and 24/7 live streaming coverage. ABC News is the home to the #1 evening newscast “World News Tonight” with David Muir, “Good Morning America,” “20/20,” “Nightline,” “This Week” with George Stephanopoulos, “ABC News Live Prime” with Linsey Davis, plus the daily news podcast “Start Here.” Connect with ABC News on social media: Facebook:

• ABC World News Tonight with David Mui… Read ABC News reports online: http://abcnews.go.com ABC News Digital is your daily source of breaking national and world news, exclusive interviews and 24/7 live streaming coverage. ABC News is the home to the #1 evening newscast “World News Tonight” with David Muir, “Good Morning America,” “20/20,” “Nightline,” “This Week” with George Stephanopoulos, “ABC News Live Prime” with Linsey Davis, plus the daily news podcast “Start Here.” Connect with ABC News on social media: Facebook: ![]() / abcnews Instagram:

/ abcnews Instagram: ![]() / abcnews TikTok:

/ abcnews TikTok: ![]() / abcnews X:

/ abcnews X: ![]() / abc Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abcnews LinkedIn:

/ abc Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abcnews LinkedIn: ![]() / abcnews #space #nasa #astronauts #news #abcnews #blackhistory

/ abcnews #space #nasa #astronauts #news #abcnews #blackhistory

Transcript

Follow along using the transcript.

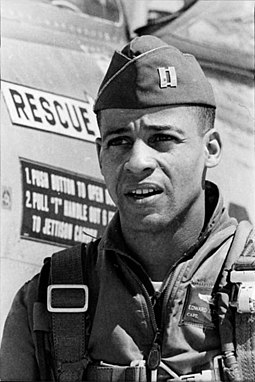

Ed Dwight

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Not to be confused with Ed White (astronaut).

|

Edward J. Dwight Jr. |

|

|

Dwight while serving as a captain in the United States Air Force |

|

| Born | Edward Joseph Dwight Jr.

September 9, 1933 (age 90) Kansas City, Kansas, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Awards | Air Force Commander’s Award for Public Service |

|

Military career |

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1953–1966 |

| Rank | |

| Website | www.eddwight.com |

Edward Joseph “Ed” Dwight Jr. (born September 9, 1933) is an American sculptor, author, and former test pilot. He is the first African American to have entered the Air Force training program from which NASA selected astronauts. He was controversially not selected to officially join NASA.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Dwight was born on September 9, 1933, in the racially segregated[1]Kansas City, Kansas area, to Georgia Baker Dwight (1909–2006) and Edward Joseph Dwight Sr. (1905–1975), who played second base and centerfield for the Kansas City Monarchs and other Negro league teams from 1924 to 1937.[2][3][4][5]

At age 4, Dwight built a toy airplane out of orange crates in his backyard.[1] As a child, he was an avid reader and talented artist who was mechanically gifted and enjoyed working with his hands.[2] He attended grade school at Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Kansas City. While delivering newspapers, he saw Air Force pilot Dayton Ragland, a Black man from Kansas City, on the front page of The Call. Having grown up in racist segregation, he instantly “wigged out”, becoming inspired to follow this career path while thinking “This is insane. I didn’t even know they let black pilots get anywhere near airplanes. … Where did he get trained? How did he get in the military? How did all this stuff happen right before my nose?”.[1] In 1951, he became the first African-American male to graduate from Bishop Ward High School, a private Catholic high school in Kansas City, Kansas. He was a member of the National Honor Society and earned a scholarship to attend the Kansas City Art Institute.[6][7][8] Dwight enrolled in Kansas City Junior College (later renamed Metropolitan Community College) and graduated with an Associate of Arts degree in engineering in 1953.

Career[edit]

Piloting[edit]

Captain Edward J. Dwight Jr. in US Air Force.jpg

Created: 1960

Dwight enlisted in the United States Air Force in 1953.[9] He completed his airman and cadet pre-flight training at Lackland Air Force Base near San Antonio, Texas. He then traveled to Malden Air Base in Malden, Missouri, to finish his primary flight training. He earned a commission as an Air Force second lieutenant in 1955 before being assigned to Williams Air Force Base, southeast of Phoenix, Arizona.[6][7]

While training to become a test pilot, Dwight attended night classes at Arizona State University. In 1957, he graduated cum laude with a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering.[2][6][7][9] Dwight later completed Air Force courses in experimental test piloting and aerospace research at Edwards Air Force Base in 1961 and 1962, respectively.[10] He earned the rank of captain while serving in the Air Force.[11]

Pre-astronaut training[edit]

In 1961, Chuck Yeager was running the Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS), a US Air Force program that had sent some of its graduates into the NASA Astronaut Corps. Yeager said Curtis LeMay called and told him, “Bobby Kennedy wants a colored in space. Get one into your course.”[12] Dwight was selected to enter ARPS shortly after that phone call. Dwight has said that Whitney Young of the National Urban League put the idea of a Black astronaut in President Kennedy’s head during a meeting with Kennedy, Young, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and A. Philip Randolph. However, in Dwight’s telling, this meeting happened in 1959, when Whitney Young was an unknown college administrator. Young’s biographer says that this meeting did not happen.[13] Nonetheless, Dwight’s selection into this Air Force program garnered international media attention, and Dwight appeared on the covers of news magazines such as Ebony, Jet,[14] and Sepia.[2][11][15]

Dwight proceeded to Phase II of (ARPS) [16] but was not selected by NASA to be an astronaut. He resigned from the Air Force in 1966, claiming, according to The Guardian, that “racial politics had forced him out of NASA and into the regular officer corps”.[15][17][18][19]

In August 2020, Dwight was made an honorary Space Force member in Washington, D.C.[20]

Sculpting[edit]

After resigning from the Air Force, Dwight worked as an engineer, in real estate, and for IBM.[9] He opened a barbecue restaurant in Denver.[21] Dwight was also a successful construction entrepreneur and occasionally “built things with scrap metal”. Dwight’s artistic interest in sculpting and interest in learning about black historical icons grew after Colorado’s first black lieutenant governor, George L. Brown, commissioned him to create a statue for the state capitol building in 1974.[17] Upon completion, Dwight moved to Denver and earned an M.F.A. in sculpture from the University of Denver in 1977.[11] He learned how to operate the University of Denver‘s metal casting foundry in the mid-1970s.[2][11]

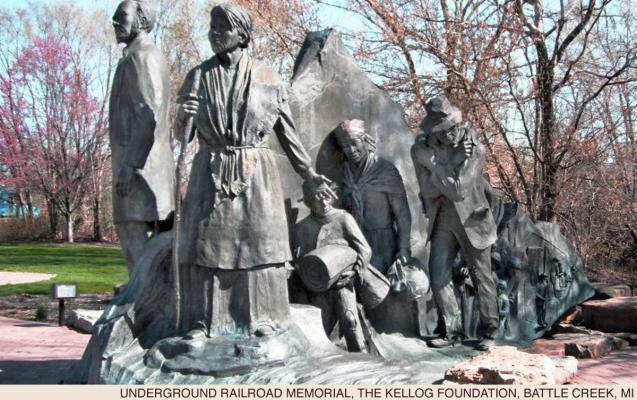

Dwight has been recognized for his innovative use of negative space in sculpting.[2] Each of his pieces involves Blacks and civil rights activists, with a focus on the themes of slavery, emancipation, and post-reconstruction.[17] Most of the pieces depict only Black people, but the Underground Railroad Sculpture in Battle Creek also honors Erastus and Sarah Hussey, who were conductors on the Underground Railroad. Dwight’s first major work was a commission in 1974 to create a sculpture of Colorado Lieutenant GovernorGeorge L. Brown. Soon after, he was commissioned by the Colorado Centennial Commission to create a series of bronze sculptures entitled “Black Frontier in the American West”.[9]

Soon after his completion of the “Black Frontier in the American West” exhibit, Dwight created a series of more than seventy bronze sculptures at the St. Louis Arch Museum at the request of the National Park Service. The series, “Jazz: An American Art Form”, depicts the evolution of jazz and features jazz performers such as Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Benny Goodman, and Charlie Parker.[9]

Dwight owns and operates Ed Dwight Studios, based in Denver.[2] Its 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2). facility houses a studio, gallery, foundry, and a large collection of research material.[22][17] The gallery and studio is open to the public.

Awards and honors[edit]

- 1986 – Honorary doctorate from Arizona State University[23]

- 2020 – Air Force Commander’s Award for Public Service[24]

- 2020 – Bonfils-Stanton Foundation Artist Award[25]

- 2021 – Asteroid 92579 Dwight[26]

- 2022 – University of Denver CAHSS Lifetime Achievement Award[27]

Personal life[edit]

Dwight was raised Catholic, and served as an altar boy.[28] In 1997, he was the lead sculptor on the statue of the Madonna and Child for the Our Mother of Africa Chapel, a structure devoted to African-American Catholics in the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, the largest church in North America. Dwight was the only black artist involved in the project. He was inducted into Phi Beta Sigma fraternity as an honorary brother at their 2023 conclave, held in Houston, Texas.[29]

Sculptures[edit]

As of late 2019, Dwight has created 129 memorial sculptures and over 18,000 gallery pieces, which include paintings and sculptures.[30] His works include these:[31]

|

Name |

Picture |

Location |

Unveiled |

Notes |

| African American History Monument |  |

South Carolina State House grounds – Columbia, South Carolina | March 29, 2001 | [2][31] |

| Alex Haley / Kunta Kinte Memorial | The City Dock – Annapolis, Maryland | December 1999 | [2][31] | |

| Black Revolutionary War Patriots Memorial | Constitution Gardens – Washington, D.C. | 1991 | [2] | |

| Captain Walter Dyett Statue | Chicago, Illinois | [31] | ||

| Concerto | Folly Theater – Kansas City, Missouri | [31] | ||

| Dr. Benjamin Mays | Morehouse College Commons – Atlanta, Georgia | [31] | ||

| Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. | Anne Arundel Community College – Annapolis, Maryland | 2006 | [31] | |

| Statue of Martin Luther King Jr. | Houston, Texas | 2007 | [31] | |

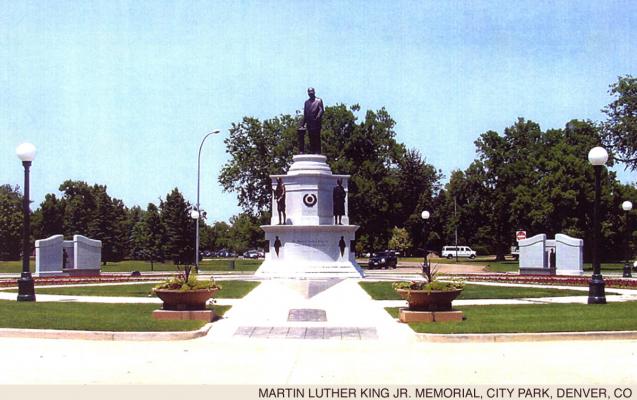

| Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial | City Park – Denver, Colorado | 2002 | [2][31] | |

| Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. & Coretta Scott King | Allentown, Pennsylvania | 2011 | [31] | |

| Gateway to Freedom International Memorial to the Underground Railroad | Philip A. Hart Plaza – Detroit, Michigan | 2001 | [2][31][32] | |

| George Washington Williams bust | Ohio Statehouse – Columbus, Ohio | [2] | ||

| Hank Aaron | Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium – Atlanta, Georgia | 1982 | [31][4] | |

| Inauguration of History and Hope – Inaugural Sculpture Scene of President Barack Obama | Touring exhibit | 2010 | [31] | |

| Jack Trice Memorial | Iowa State University – Ames, Iowa | [31] | ||

| Jazz: An American Art Form | St. Louis Arch Museum – St. Louis, Missouri | [9] | ||

| John Hope Franklin Tower of Reconciliation | Tulsa, Oklahoma | [31] | ||

| Mayor Harold Washington | Harold Washington Cultural Center – Chicago, Illinois | 2004 | [31] | |

| Memorial to Rosa Parks, Mother of the Civil Rights Movement | Grand Rapids, Michigan | 2010 | [31] | |

| Mother of Africa Chapel | Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception – Washington, D.C. | 1997 | [31] | |

| Mr. Frederick Douglass | Frederick Douglass National Historic Site – Washington, D.C. | 1980 | Dwight’s first commission[31] | |

| Quincy Jones Sculpture Park | Chicago, Illinois | [2] | ||

| Soldiers Memorial | Lincoln University – Jefferson City, Missouri | 2007 | [31] | |

| Texas African American History Memorial | Texas State Capitol – Austin, Texas | November 19, 2016 | [33] Erected by the Texas African American History Memorial Foundation. | |

| Tower of Freedom International Memorial to the Underground Railroad |  |

Civic Esplanade – Windsor, Ontario | 2001 | [2][31][32] |

| Underground Railroad Memorial | Kellogg Foundation headquarters – Battle Creek, Michigan | 1994 | [31] | |

| United House of Prayer for All People | Lincoln Cemetery – Suitland, Maryland | 2008 | [31] | |

| William E. Smith, Director of Airports | Denver, Colorado | [31] | ||

| Denmark Vesey Monument | Charleston, South Carolina | 2014 | [34] |

New Texas African American Monument

This entry was posted on February 14, 2017 at 11:20 AM

posted by TexasLRL in Texas history

The newest monument on the Texas Capitol grounds, unveiled on November 19, 2016, is dedicated to African Americans in Texas. Located on the South Capitol grounds, the monument is made up of bronze panels depicting the historical contributions of African Americans to Texas over the state’s long history.

Legislative History

The monument has a legislative history that goes back over 25 years. In 1991, Sen. Rodney Ellis and Rep. Al Edwards passed SCR 49, 72R, directing the State Preservation Board to explore opportunities to revere and honor some of the outstanding historical figures from all ethnic cultures with regard to new monuments on the Capitol grounds. In the following session in 1993, Ellis and Rep. Garnet Coleman passed SCR 97, 73R, directing the State Preservation Board to include in its long-range master plan for the Capitol grounds a permanent monument in tribute to African American and Mexican American Texans.

Later, in 1997, Rep. Al Edwards and Sen. Jerry Patterson passed HB 1216, 75R. The bill created the Texas Emancipation Juneteenth Cultural and Historical Commission and gave it a mission to collect and commemorate the history of Juneteenth, the day that marks the arrival of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in Texas. At that time, Edwards envisioned the monument as an Emancipation Juneteenth memorial monument.

The 1997 bill was followed by several more legislative measures:

• HB 1865, 76R, by Edwards and Sen. Royce West, Relating to the operations of the Texas Emancipation Juneteenth Cultural and Historical Commission.

• HB 1368, 76R, by Edwards and Sen. Chris Harris, Relating to the site of the Emancipation Juneteenth memorial monument.

• HCR 176, 81R, by Edwards and Sen. Tommy Williams, Expressing continued support for the establishment of a Juneteenth memorial monument on the grounds of the State Capitol at the location previously approved by the State Preservation Board.

In 2011, during the 82nd Regular Session, legislators expanded the scope of the monument to provide a broader representation of African American history in Texas. The bill that made these changes was SB 1928, 82R (by Ellis and Rep. Alma Allen), relating to an African American Texans memorial monument on the Capitol grounds; SCR 51, 82R (by Ellis and Allen) expressed the legislature’s support for this shift in the monument’s subject matter. The dedication program includes lists of those who served on the Texas African American History Memorial Committee, donors, and others who have been involved with the project.

The monument features notable Texas African Americans including Estevanico de Dorantes (the first African to set foot on Texas soil), Hendrick Arnold (a special agent in the Battle of the Republic and in the Indian wars), and Sam McCullough (one of the first casualties of the Texas Revolution). Emancipation is the central core element of the memorial, featuring a 9-foot-high image of a male and female slave having broken the bonds of slavery, dedicated to the 182,500 slaves that were freed on June 19, 1865. Also illustrated are the slave experience, from arrival to slaves’ work in the fields and industry, and depictions of Black Texans’ contributions to the state, from the Buffalo Soldiers to musicians to astronauts. To learn more about the monument, please see https://tspb.texas.gov/prop/tcg/tcg-monuments/21_african_american_history/index.html.

Did you know?

Ed Dwight, the sculptor who designed and created the African American Texans monument, also created the memorial to Congressman (and former Texas legislator) Mickey Leland at Houston’s Intercontinental Airport.

This entry was posted on February 14, 2017 at 11:20 AM and has received 6651 views. Print this entry.

For more information, please visit the following Link:

https://lrl.texas.gov/whatsnew/client/index.cfm/2017/2/14/New-Texas-African-American-Monument

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

||

|

Artist |

Ed Dwight | |

|

Year |

2016 | |

|

Location |

Austin, Texas, United States | |

The Texas African American History Memorial is an outdoor monument commemorating the impact of African Americans in Texas, installed on the Texas State Capitol grounds in Austin, Texas, United States. The memorial was sculpted by Ed Dwight and erected by the Texas African American History Memorial Foundation in 2016. It describes African American history from the 1500s to present, and includes depictions of Hendrick Arnold and Barbara Jordan, as well as Juneteenth (June 19, 1865), when African Americans were emancipated.[1]

For more information, please visit the following Link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Texas_African_American_History_Memorial

The story of Granny Hayden, a Black midwife who was born into slavery | PBS News Weekend

Laura Barrón-López:

The recent threats of civil war among radicalized Trump supporters are not isolated. Five years ago today, white supremacist and neo-Nazis marched on Charlottesville, Virginia, in a violent demonstration.

Mary Stepp Burnette Hayden was born into slavery on a plantation in Black Mountain, North Carolina. She remained there after being freed in 1865, going on to become a midwife. In this animated feature from our partners at StoryCorps, Hayden’s granddaughter Mary Othella Burnette tells her great-granddaughter, Debora Hamilton Palmer, about their family matriarch.

Read the Full Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

- John Yang:

For Black History Month, our partners at StoryCorps are amplifying black voices with conversations about activism, love, joy and leadership. Tonight, the story of Mary Stepp Burnette Hayden. She was born into slavery on a plantation in Black Mountain, North Carolina, after she was freed in 1865 when she was seven, she remained there going on to become a midwife.

At StoryCorps, Hayden’s granddaughter Mary Othella Burnette told her great granddaughter Deborah Hamilton Palmer, about their family matriarch.

- Mary Othella Burnette:

She probably weighed not more than 110 pounds. She was about four feet 11 inches tall, and her hair hung well below her waist. She had deep set eyes and a fierce look as if she were looking right through you.

- Deborah Hamilton Palmer:

What was your relationship with her like mom?

- Mary Othella Burnette:

She delivered me. She used to tell me how I started her and my dad a few minutes after I was born by opening my eyes and turning my head to look around the room. And she said, God, look at that.

My grandmother love to talk and most of our stores are bad. But granny’s stories were real life stories. She didn’t know anything about Hansel and Gretel. Here is this woman, a former slave walking around delivering babies and helping people. You have to understand that back when grannies started there were no hospitals for black people to go to and poor people had no money to pay for professional medical care. So if you had a disease that could not be treated by midwife, you died at home.

Houses could be several miles apart, and bears commonly roamed the neighborhoods. But she walked. If somebody needed help, Granny was going black and whites alike. It made no difference to her. She was fearless. You know, you never boasted about what she did.

But she probably caught several 100 babies, if not more.

- Deborah Hamilton Palmer:

How old was going ahead and when she stopped her practice?

- Mary Othella Burnette:

She was about 90 years old. She was a very strong little woman. You know, when people think about slavery, they think about hundreds of years ago, not about somebody who died in 1956. She was a pillar, not only in our family, but in our community.

And I assume she would always be there. Like when you’re a child, you assume everything’s going to be there. But I’m very proud to have descended from someone like my grandmother. Very, very proud.

Go Deeper

Leave a Reply