Photograph and Artwork by Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts

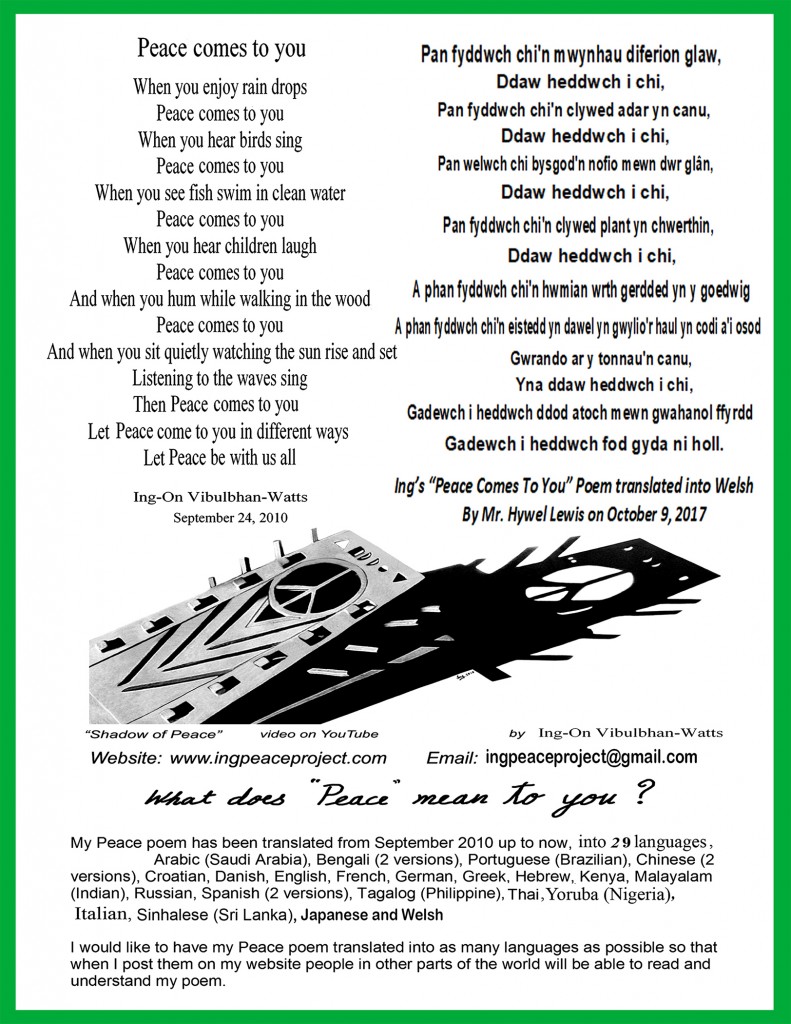

Ing’s “Peace Comes To You”Poem translated into Welsh By Mr. Hywel Lewis on October 9, 2017

Sent: 09 October 2017 19:38

From: Lewis, Hywel Subject: poem

Pan fyddwch chi’n mwynhau diferion glaw,

Ddaw heddwch i chi,

Pan fyddwch chi’n clywed adar yn canu,

Ddaw heddwch i chi,

Pan welwch chi bysgod’n nofio mewn dwr glân,

Ddaw heddwch i chi,

Pan fyddwch chi’n clywed plant yn chwerthin,

Ddaw heddwch i chi,

A phan fyddwch chi’n hwmian wrth gerdded yn y goedwig

Ddaw heddwch i chi,,

A phan fyddwch chi’n eistedd yn dawel yn gwylio’r haul yn codi a’i osod

Gwrando ar y tonnau’n canu,

Yna ddaw heddwch i chi,

Gadewch i heddwch ddod atoch mewn gwahanol ffyrdd

Gadewch i heddwch fod gyda ni holl.

Ing’s comments:

I was very lucky when I went to Swansea, Wales in October 2017. A friend came to visit us with her three daughters and her sister with one daughter. They made us very happy from their visit and all of them read my “Peace Comes to You” poem aloud for me to record their voices. They also wrote their peace comments from my Peace Project “What does Peace mean to you?” on my large Peace Poster. The girls enjoyed drawing artwork and writing their expressions on Peace. I was doubly lucky to have Mr. Hywel Lewis, who works at the Swansea Library, being kind enough to translate my poem “Peace Comes To You” into Welsh. Mr. Lewis also read my poem both in Welsh and in English for me to record. John went to Swansea many times to visit his sister but was unable to find anyone to translate my Peace Poem. John is Welsh, I thought that it is important for me to have a Welsh translation for my Peace Poem. I already have my Peace Poem translated into 28 languages and the Welsh translation added to this number made the total 29. I was so lucky, happy and grateful to receive this help, that I felt much better even though I had bad cold for the entire time of my trip to the UK.

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Wednesday, December 27, 2017

Ing’s “Peace Comes To You” Poem in English and Welsh translated into Welsh By Mr. Hywel Lewis on October 9, 2017

Welsh (Cymraeg or y Gymraeg, pronounced Welsh pronunciation: [k?m?rai?, ? ??m?rai?] ( listen)) is a member of the Brittonic branch of the Celtic languages. It is spoken natively in Wales, by few in England, and in Y Wladfa (the Welsh colony in Chubut Province, Argentina).[10] Historically, it has also been known in English as “Cambrian”,[11] “Cambric”[12] and “Cymric”.[13]

The United Kingdom Census 2011 recorded that 19% of people aged three and over who live in Wales can speak Welsh, a decrease from the 20.8% recorded in 2001. An overall increase in the size of the Welsh population, most of whom are not Welsh speakers, appears to correspond with a fall in the number of Welsh speakers in Wales – from 582,000 in 2001 to 562,000 in 2011. This figure is still a greater number, however, than the 508,000 (18.7%) of people who said that they could speak Welsh in 1991. According to the Welsh Language Use Survey 2013–15, 24% of people aged three and over living in Wales were able to speak Welsh, demonstrating a possible increase in the prevalence of the Welsh language.[14]

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_language

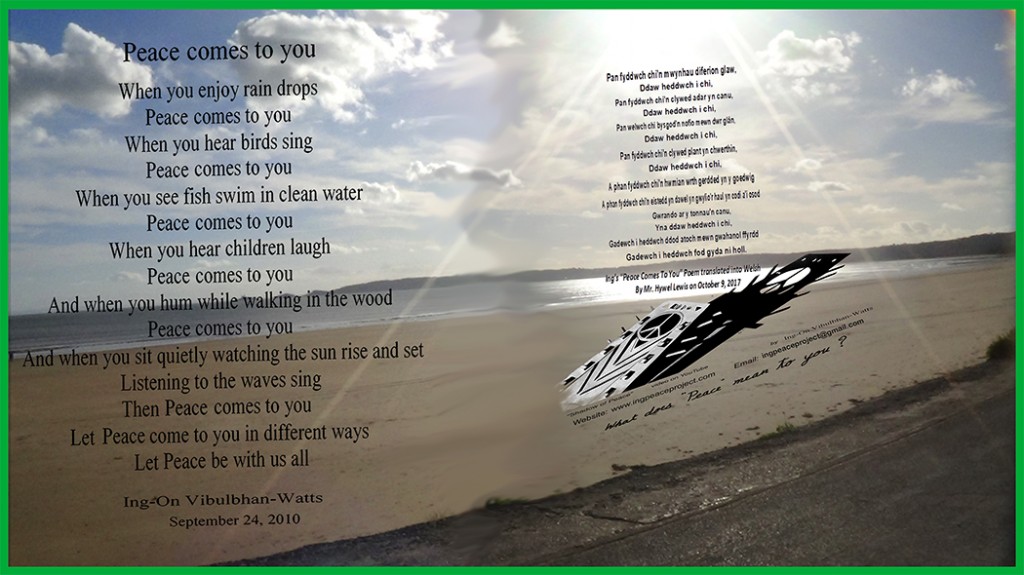

Ing’s “Peace Comes To You” Poem in English and Welsh translated into Welsh by Mr. Hywel Lewis on October 9, 2017 and Swansea Bay, Swansea, Wales, UK

“Welsh orthography: Welsh is written in a Latin alphabet traditionally consisting of 28 letters, of which eight are digraphs treated as single letters for collation:

a, b, c, ch, d, dd, e, f, ff, g, ng, h, i, l, ll, m, n, o, p, ph, r, rh, s, t, th, u, w, y

In contrast to English practice, “w” and “y” are considered vowel letters in Welsh along with “a”, “e”, “i”, “o” and “u”.

The letter “j” is used in many everyday words borrowed from English, like jam, jôc “joke” and garej “garage”. The letters “k”, “q”, “v”, “x”, and “z” are used in some technical terms, like kilogram, volt and zero, but in all cases can be, and often are, replaced by Welsh letters: cilogram, folt and sero.[75] The letter “k” was in common use until the sixteenth century, but was dropped at the time of the publication of the New Testament in Welsh, as William Salesbury explained: “C for K, because the printers have not so many as the Welsh requireth”. This change was not popular at the time.[76]

The most common diacritic is the circumflex, which disambiguates long vowels, most often in the case of homographs, where the vowel is short in one word and long in the other: e.g. man “place” vs mân “fine”, “small”.

Morphology

Main articles: Colloquial Welsh morphology and Literary Welsh morphology

Welsh morphology has much in common with that of the other modern Insular Celtic languages, such as the use of initial consonant mutations and of so-called “conjugated prepositions” (prepositions that fuse with the personal pronouns that are their object). Welsh nouns belong to one of two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine, but they are not inflected for case. Welsh has a variety of different endings and other methods to indicate the plural, and two endings to indicate the singular of some nouns. In spoken Welsh, verbal features are indicated primarily by the use of auxiliary verbs rather than by the inflection of the main verb. In literary Welsh, on the other hand, inflection of the main verb is usual.”

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_language

Ing’s “Peace Comes To You” Poem in Welsh translated into Welsh

By Mr. Hywel Lewis on October 9, 2017, Swansea Bay, Swansea, Wales, UK

“Welsh numerals

The traditional counting system used in the Welsh language is vigesimal, i.e. it is based on twenties, as in standard French numbers 70 (soixante-dix, literally “sixty-ten”) to 99 (quatre-vingt-dix-neuf, literally “four score nineteen”). Welsh numbers from 11 to 14 are “x on ten” (e.g. un ar ddeg: 11), 16 to 19 are “x on fifteen” (e.g. un ar bymtheg: 16), though 18 is deunaw, “two nines”; numbers from 21 to 39 are “1–19 on twenty”, 40 is deugain “two twenties”, 60 is trigain “three twenties”, etc. This form continues to be used, especially by older people, and it is obligatory in certain circumstances (such as telling the time, and in ordinal numbers).[77]

There is also a decimal counting system, which has become relatively widely used, though less so in giving the time, ages, and dates (it features no ordinal numbers). This system is in especially common use in schools due to its simplicity, and in Patagonian Welsh. Whereas 39 in the vigesimal system is pedwar ar bymtheg ar hugain (“four on fifteen on twenty”) or even deugain namyn un (“two score minus one”), in the decimal system it is tri deg naw (“three tens nine”).

Although there is only one word for “one” (un), it triggers the soft mutation (treiglad meddal) of feminine nouns, where possible, other than those beginning with “ll” or “rh”. There are separate masculine and feminine forms of the numbers “two” (dau and dwy), “three” (tri and tair) and “four” (pedwar and pedair), which must agree with the grammatical gender of the objects being counted. The objects being counted appear in the singular, not plural form.”

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_language

Adelaide Dupont’s comments:

#welsh is a very #peaceful #language.

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts: +Adelaide Dupont Thank you for your comment

Have A Wonderful New Year

Adelaide Dupont: +Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts I appreciate your #newyear #wishes!

Ing’s “Peace Comes To You” Poem translated into Welsh

By Mr. Hywel Lewis on October 9, 2017 and “The Flag of Wales”

“The Flag of Wales (Y Ddraig Goch) incorporates the red dragon, a popular symbol of Wales and the Welsh people, along with the Tudor colours of green and white. It was used by Henry VII at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, after which it was carried in state to St. Paul’s Cathedral. The red dragon was then included in the Tudor royal arms to signify their Welsh descent. It was officially recognised as the Welsh national flag in 1959. Since the British Union Flag does not have any Welsh representation, the Flag of Wales has become very popular.”

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_people

Ing’s “Peace Comes To You” Poem in English and Swansea Bay, Swansea, Wales, UK

Welsh syntax

The canonical word order in Welsh is verb–subject–object.

Colloquial Welsh inclines very strongly towards the use of auxiliaries with its verbs, as in English. The present tense is constructed with bod (“to be”) as an auxiliary verb, with the main verb appearing as a verbnoun (used in a way loosely equivalent to an infinitive) after the particle yn:

Mae Siân yn mynd i Lanelli

Siân is going to Llanelli.

There, mae is a third-person singular present indicative form of bod, and mynd is the verbnoun meaning “to go”. The imperfect is constructed in a similar manner, as are the periphrastic forms of the future and conditional tenses.

In the preterite, future and conditional mood tenses, there are inflected forms of all verbs, which are used in the written language. However, speech now more commonly uses the verbnoun together with an inflected form of gwneud (“do”), so “I went” can be Mi es i or Mi wnes i fynd (“I did go”). Mi is an example of a preverbal particle; such particles are common in Welsh.

Welsh lacks separate pronouns for constructing subordinate clauses; instead, special verb forms or relative pronouns that appear identical to some preverbal particles are used.

Possessives as direct objects of verbnouns

The Welsh for “I like Rhodri” is Dw i’n hoffi Rhodri (word for word, “am I [the] liking [of] Rhodri”), with Rhodri in a possessive relationship with hoffi. With personal pronouns, the possessive form of the personal pronoun is used, as in “I like him”: Dw i’n ei hoffi, literally, “am I his liking” – “I like you” is Dw i’n dy hoffi (“am I your liking”).

Pronoun doubling

In colloquial Welsh, possessive pronouns, whether they are used to mean “my”, “your”, etc. or to indicate the direct object of a verbnoun, are commonly reinforced by the use of the corresponding personal pronoun after the noun or verbnoun: ei d? e “his house” (literally “his house of him”), Dw i’n dy hoffi di “I like you” (“I am [engaged in the action of] your liking of you”), etc. It should be noted that the “reinforcement” (or, simply, “redoubling”) adds no emphasis in the colloquial register. While the possessive pronoun alone may be used, especially in more formal registers, as shown above, it is considered incorrect to use only the personal pronoun. Such usage is nevertheless sometimes heard in very colloquial speech, mainly among young speakers: Ble ‘dyn ni’n mynd? T? ti neu d? fi? (“Where are we going? Your house or my house?”).

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_language

Ing’s “Peace Comes To You” Poem translated into Welsh

By Mr. Hywel Lewis on October 9, 2017 and Swansea Bay at the back of Swansea Library, Swansea, Wales, UK

Photograph and Artwork by Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts

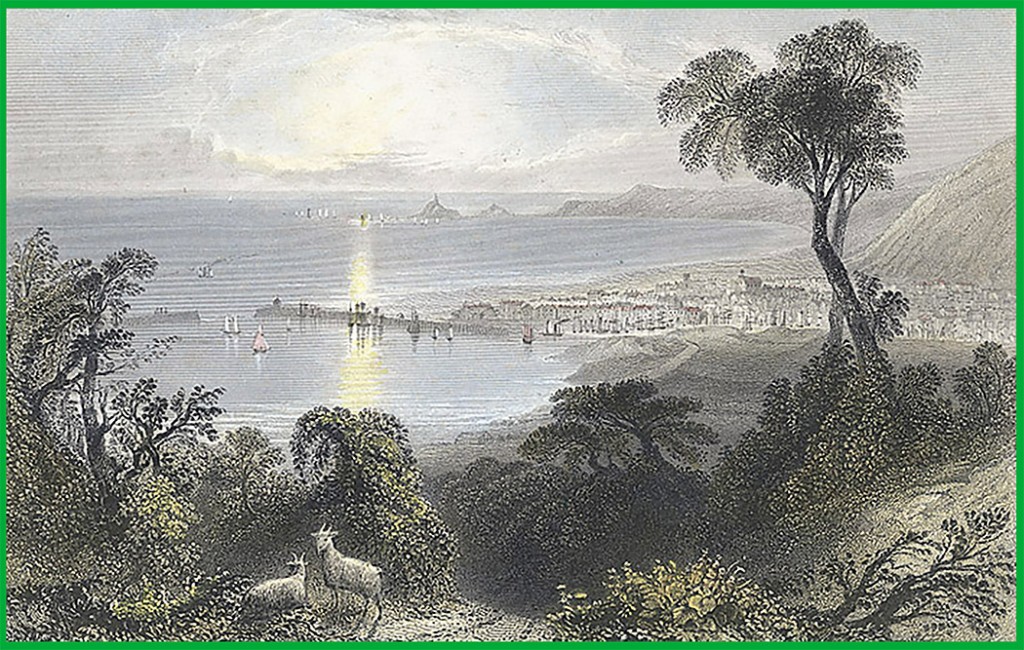

Swansea Bay (Welsh: Bae Abertawe) is a bay on the southern coast of Wales. The River Neath, River Tawe, River Afan, River Kenfig and Clyne River flow into the bay. Swansea Bay and the upper reaches of the Bristol Channel experience a large tidal range. The shipping ports in Swansea Bay are Swansea Docks, Port Talbot Docks and Briton Ferry wharfs.

Each stretch of beach within the bay has its own individual name:

·Aberavon Beach

·Baglan Bay

·Jersey Marine Beach

·Swansea Beach

·Mumbles Beach

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swansea_Bay

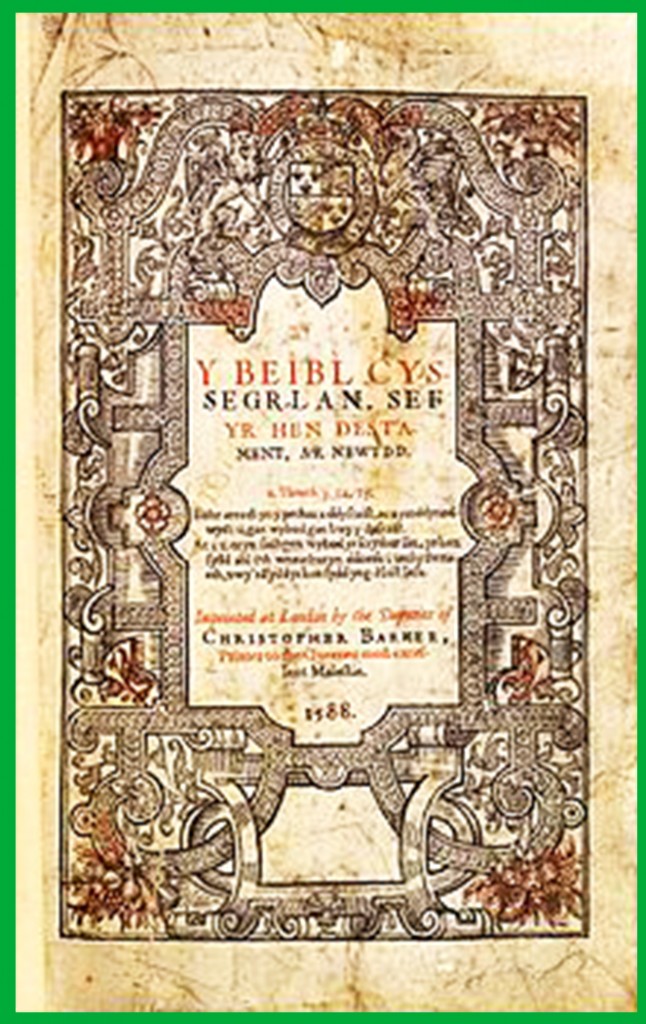

“The 1588 Welsh Bible: The Bible translations into Welsh helped maintain the use of Welsh in daily life. The New Testament was translated by William Salesbury in 1567 followed by the complete Bible by William Morgan in 1588.

The Welsh language arguably originated from the Britons at the end of the 6th century. Prior to this, three distinct languages were spoken by the Britons during the 5th and 6th centuries: Latin, Irish, and British. According to T. M. Charles-Edwards, the emergence of Welsh as a distinct language occurred towards the end of this period.[17] The emergence of Welsh was not instantaneous and clearly identifiable. Instead, the shift occurred over a long period of time, with some historians claiming that it happened as late as the 9th century. Kenneth H. Jackson proposed a more general time period for the emergence, specifically after the Battle of Dyrham, a military battle between the West Saxons and the Britons in 577 AD.[18]

Four periods are identified in the history of Welsh, with rather indistinct boundaries: Primitve Welsh, Old Welsh, Middle Welsh, and Modern Welsh. The period immediately following the language’s emergence is sometimes referred to as Primitive Welsh,[19] followed by the Old Welsh period – which is generally considered to stretch from the beginning of the 9th century to sometime during the 12th century.[19] The Middle Welsh period is considered to have lasted from then until the 14th century, when the Modern Welsh period began, which in turn is divided into Early and Late Modern Welsh.

The name Welsh originated as an exonym given to its speakers by the Anglo-Saxons, meaning “foreign speech” (see Walha)[citation needed], and the native term for the language is Cymraeg, meaning “British”.”

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_language

Swansea Bay (1840)

Bartlett, William Henry, 1809-1854, artist. Armytage, James Charles, d. 1897, engraver. – This image is available from the National Library of Wales You can view this image in its original context on the NLW Catalogue

Abstract: A view of showing Swansea bay and a town. Ships are sailing in the sea and a lighthouse can be seen in the background.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swansea_Bay

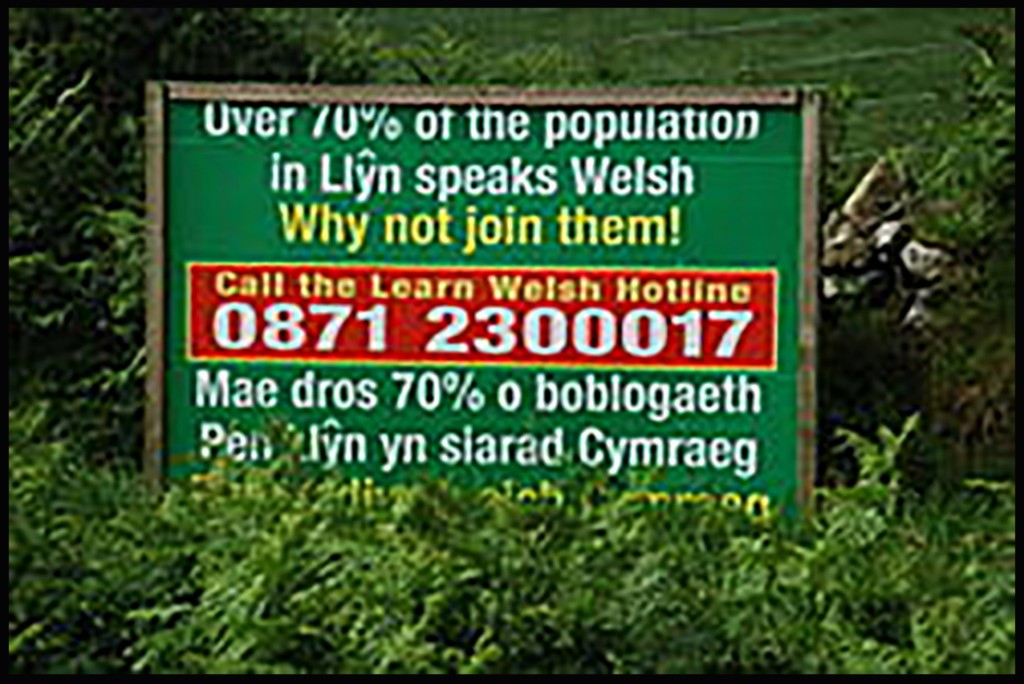

Bilingual road markings near Cardiff Airport. In Welsh-speaking areas, the Welsh signage appears first. Photograph by Adrian Pingstone

The Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011 gave the Welsh language official status in Wales,[15] making it the only language that is de jure official in any part of the United Kingdom, with English being de facto official. Thus, official documents and procedures require Welsh and English to be given equality in the conduct of the proceedings of the National Assembly for Wales.[16]

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_language

Trilingual (Spanish, Welsh and English) sign in Argentina

Gastón Cuello – Own work

Sign at former Gaiman Station of the Central Chubut Railway

Sign promoting the learning of Welsh: Alan Fryer

Defnyddiwch eich Cymraeg – Use your Welsh. Detail of 488575

Origins

See also: Celtic languages § Classification

Welsh evolved from Common Brittonic, the Celtic language spoken by the ancient Celtic Britons. Classified as Insular Celtic, the British language probably arrived in Britain during the Bronze Age or Iron Age and was probably spoken throughout the island south of the Firth of Forth.[20] During the Early Middle Ages the British language began to fragment due to increased dialect differentiation, thus evolving into Welsh and the other Brittonic languages. It is not clear when Welsh became distinct.[18][21][22]

Kenneth H. Jackson suggested that the evolution in syllabic structure and sound pattern was complete by around 550, and labelled the period between then and about 800 “Primitive Welsh”.[18] This Primitive Welsh may have been spoken in both Wales and the Hen Ogledd (“Old North”) – the Brittonic-speaking areas of what is now northern England and southern Scotland – and therefore may have been the ancestor of Cumbric as well as Welsh. Jackson, however, believed that the two varieties were already distinct by that time.[18] The earliest Welsh poetry – that attributed to the Cynfeirdd or “Early Poets” – is generally considered to date to the Primitive Welsh period. However, much of this poetry was supposedly composed in the Hen Ogledd, raising further questions about the dating of the material and language in which it was originally composed.[18] This discretion stems from the fact that Cumbric was widely believed to have been the language used in Hen Ogledd. An 8th century inscription in Tywyn shows the language already dropping inflections in the declension of nouns.[23]

Janet Davies proposed that the origins of Welsh language were much less definite; in The Welsh Language: A History, she proposes that Welsh may have been around even earlier than 600 AD. This is evidenced by the dropping of final syllables from Brittonic: *bardos “poet” became bardd, and *abona “river” became afon.[21] Though both Davies and Jackson cite minor changes in syllable structure and sounds as evidence for the creation of Old Welsh, Davies suggests it may be more appropriate to refer to this derivative language as Lingua Brittanica rather than characterizing it as a new language altogether.

Sculpture of Owain Glynd?r, the last native Welsh person to hold the title Prince of Wales

Primitive Welsh

The argued dates for the period of “Primitive Welsh” are widely debated, with some historians’ suggestions differing by hundreds of years.

Old Welsh

The next main period is Old Welsh (Hen Gymraeg, 9th to 11th centuries); poetry from both Wales and Scotland has been preserved in this form of the language. As Germanic and Gaelic colonisation of Britain proceeded, the Brittonic speakers in Wales were split off from those in northern England, speaking Cumbric, and those in the southwest, speaking what would become Cornish, and so the languages diverged. Both the works of Aneirin (Canu Aneirin, c. 600) and the Book of Taliesin (Canu Taliesin) were during this era.

Middle Welsh

Middle Welsh (Cymraeg Canol) is the label attached to the Welsh of the 12th to 14th centuries, of which much more remains than for any earlier period. This is the language of nearly all surviving early manuscripts of the Mabinogion, although the tales themselves are certainly much older. It is also the language of the existing Welsh law manuscripts. Middle Welsh is reasonably intelligible to a modern-day Welsh speaker.

The famous cleric Gerald of Wales tells, in his Descriptio Cambriae, a story of King Henry II of England. During one of the King’s many raids in the 12th century, Henry asked an old man of Pencader, Carmarthenshire whether the Welsh people could resist his army. The old man replied:

It can never be destroyed through the wrath of man, unless the wrath of God shall concur. Nor do I think that any other nation than this of Wales, nor any other language, whatever may hereafter come to pass, shall in the day of reckoning before the Supreme Judge, answer for this corner of the Earth.[24]

Modern Welsh

Modern Welsh is subdivided within itself into Early Modern and Late Modern Welsh.Early Modern Welsh ran from the 15th century through to the end of the 16th century, and the Late Modern Welsh period roughly dates from the 16th century onwards. Contemporary Welsh still differs greatly from the Welsh of the 16th Century, but they are similar enough that a fluent Welsh speaker should have little trouble understanding it. The Modern Welsh period is where one can see a decline in the popularity of the Welsh language, as the number of people who spoke Welsh declined to the point at which there was concern that the language would become extinct entirely. Welsh government processes and legislation have worked to increase the proliferation of the Welsh language throughout school projects and the like.

Welsh as a first language is largely concentrated in the north and west of Wales, principally Gwynedd, Conwy, Denbighshire (Sir Ddinbych), Anglesey (Ynys Môn), Carmarthenshire (Sir Gâr), north Pembrokeshire (Sir Benfro), Ceredigion, parts of Glamorgan (Morgannwg), and north-west and extreme south-west Powys, although first-language and other fluent speakers can be found throughout Wales.

Outside Wales

Welsh-speaking communities persisted well on into the modern period across the border with England. Archenfield was still Welsh enough in the time of Elizabeth I for the Bishop of Hereford to be made responsible, together with the four Welsh bishops, for the translation of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer into Welsh. Welsh was still commonly spoken here in the first half of the 19th century, and churchwardens’ notices were put up in both Welsh and English until about 1860.[31]

The number of Welsh-speaking people in the rest of Britain has not yet been counted for statistical purposes. In 1993, the Welsh-language television channel S4C published the results of a survey into the numbers of people who spoke or understood Welsh, which estimated that there were around 133,000 Welsh-speaking people living in England, about 50,000 of them in the Greater London area.[32] The Welsh Language Board, on the basis of an analysis of the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Longitudinal Study, estimated there were 110,000 Welsh-speaking people in England, and another thousand in Scotland and Northern Ireland.[33] In the 2011 Census, 8,248 people in England gave Welsh in answer to the question “What is your main language?”[34] The ONS subsequently published a census glossary of terms to support the release of results from the census, including their definition of “main language” as referring to “first or preferred language” (though that wording was not in the census questionnaire itself).[35][36] The wards in England with the most people giving Welsh as their main language were the Liverpool wards: Central and Greenbank, and Oswestry South.[34] In terms of the regions of England, North West England (1,945), London (1,310) and the West Midlands (1,265) had the highest number of people noting Welsh as their main language.[37]

In the later 19th century, virtually all teaching in the schools of Wales was in English, even in areas where the pupils barely understood English. Some schools used the Welsh Not, a piece of wood, often bearing the letters “WN”, which was hung around the neck of any pupil caught speaking Welsh. The pupil could pass it on to any schoolmate heard speaking Welsh, with the pupil wearing it at the end of the day being given a beating. One of the most famous Welsh-born pioneers of higher education in Wales was Sir Hugh Owen. He made great progress in the cause of education, and more especially the University College of Wales at Aberystwyth, of which he was chief founder. He has been credited[by whom?] with the Welsh Intermediate Education Act 1889 (52 & 53 Vict c 40), following which several new Welsh schools were built. The first was completed in 1894 and named Ysgol Syr Hugh Owen.

Towards the beginning of the 20th century this policy slowly began to change, partly owing to the efforts of Owen Morgan Edwards when he became chief inspector of schools for Wales in 1907.

The Aberystwyth Welsh School (Ysgol Gymraeg Aberystwyth) was founded in 1939 by Sir Ifan ap Owen Edwards, the son of O.M. Edwards, as the first Welsh Primary School.[52] The headteacher was Norah Isaac. Ysgol Gymraeg is still a very successful school, and now there are Welsh language primary schools all over the country. Ysgol Glan Clwyd was established in Rhyl in 1955 as the first Welsh language school to teach at the secondary level.[53]

Examples of sentences in literary and colloquial Welsh

|

English |

Literary Welsh |

Colloquial Welsh |

| I get up early every day. | Codaf yn gynnar bob dydd. | Dw i’n codi’n gynnar bob dydd. (North) Rwy’n codi’n gynnar bob dydd. (South) |

| I’ll get up early tomorrow. | Codaf yn gynnar yfory. | Mi goda i’n gynnar fory Wna i godi’n gynnar fory |

| He had not stood there long. | Ni safasai yno yn hir.[82] | Doedd o ddim wedi sefyll yno’n hir. (North) (D)ôdd e ddim wedi sefyll yna’n hir. (South) |

| They’ll sleep only when there’s a need. | Ni chysgant ond pan fo angen. | Fyddan nhw’n cysgu ddim ond pan fydd angen. |

In fact, the differences between dialects of modern spoken Welsh pale into insignificance compared to the difference between some forms of the spoken language and the most formal constructions of the literary language. The latter is considerably more conservative and is the language used in Welsh translations of the Bible, amongst other things (although the 2004 Beibl Cymraeg Newydd – New Welsh Bible – is significantly less formal than the traditional 1588 Bible). Gareth King, author of a popular Welsh grammar, observes that “The difference between these two is much greater than between the virtually identical colloquial and literary forms of English”.[83] A grammar of Literary Welsh can be found in A Grammar of Welsh (1980) by Stephen J. Williams[84] or more completely in Gramadeg y Gymraeg (1996) by Peter Wynn Thomas.[85] (No comprehensive grammar of formal literary Welsh exists in English.) An English-language guide to colloquial Welsh forms and register and dialect differences is “Dweud Eich Dweud” (2001, 2013) by Ceri Jones.[86]

Welsh emigration

Flag of the city of Puerto Madryn, Argentina, inspired by the Flag of Wales, owing to the Welsh immigration

There has been migration from Wales to the rest of Britain throughout its history. During the Industrial Revolution thousands of Welsh people migrated, for example, to Liverpool and Ashton-in-Makerfield.[72][73] As a result, some people from England, Scotland and Ireland have Welsh surnames.[74][75][76][77]

John Adams, the second President of the United States (1797–1801), whose paternal great-grandfather David Adams was born and bred at “Fferm Penybanc”, Llanboidy, Carmarthenshire, Wales[78] and who emigrated from Wales in 1675.

Other Welsh settlers moved to other parts of Europe, concentrated in certain areas. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a small wave of contract miners from Wales arrived in Northern France; the centres of Welsh-French population are in coal mining towns of the French department of Pas-de-Calais.[citation needed] Welsh settlers from Wales (and later Patagonian Welsh) arrived in Newfoundland in the early 1900s, and founded towns Labrador‘s coast region.[citation needed] In 1852 Thomas Benbow Phillips of Tregaron established a settlement of about 100 Welsh people in the state of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil.

Internationally Welsh people have emigrated, in relatively small numbers (in proportion to population, Irish emigration to the USA may have been 26 times greater than Welsh emigration),[79] to many countries, including the USA (in particular, Pennsylvania), Canada and Y Wladfa in Patagonia, Argentina.[80][81][82] Jackson County, Ohio was sometimes referred to as “Little Wales”, and the Welsh language was commonly heard or spoken among locals by the mid 20th century.[citation needed] Malad City in Idaho, which began as a Welsh Mormon settlement, lays claim to a greater proportion of inhabitants of Welsh descent than anywhere outside Wales itself.[83] Malad’s local High School is known as the “Malad Dragons”, and flies the Welsh Flag as its school colours.[84] Welsh people have also settled in New Zealand and Australia.[79][85]

Around 1.75 million Americans report themselves to have Welsh ancestry, as did 458,705 Canadians in Canada’s 2011 census.[5][7] This compares with 2.9 million people living in Wales (as of the 2001 census).[86]

There is no known evidence which would objectively support the legend that the Mandan, a Native American tribe of the central United States, are Welsh emigrants who reached North America under Prince Madog in 1170.[87]

The Ukrainian city of Donetsk was founded in 1869 by a Welsh businessman, John Hughes (an engineer from Merthyr Tydfil) who constructed a steel plant and several coal mines in the region; the town was thus named Yuzovka (??????) in recognition of his role in its founding (“Yuz” being a Russian or Ukrainian approximation of Hughes).[88]

Former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard was born in Barry, Wales. After she suffered from bronchopneumonia as a child, her parents were advised that it would aid her recovery to live in a warmer climate. This led the family to migrate to Australia in 1966, settling in Adelaide.

For more information please visit the following link:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_language

Leave a Reply