https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BEHzeTdDWTI

PBS NewsHour Weekend full episode July 18, 2020

Jul 18, 2020 PBS NewsHour

On this edition for Saturday, July 18, remembering John Lewis, a Civil Rights Movement leader and a longtime member of Congress who died of pancreatic cancer on Friday night. Also, the U.S. records more than 70,000 COVID-19 cases for the second time in a row leading officials to start reimposing restrictions in some areas in the country. Hari Sreenivasan anchors from Florida. Stream your PBS favorites with the PBS app: https://to.pbs.org/2Jb8twG Find more from PBS NewsHour at https://www.pbs.org/newshour Subscribe to our YouTube channel: https://bit.ly/2HfsCD6

Congressman John Lewis Address | Harvard Commencement 2018

May 24, 2018 Harvard University

Congressman and Civil Rights leader John Lewis gave his address at Harvard’s 367th Commencement on May 24, 2018 at Tercentenary Theatre. For more information, visit https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/stor….

Tributes pour in memory of Congressman John Lewis

Jul 18, 2020 CBS News

Countless tributes are pouring in to memorialize the life and legacy of civil rights leader and longtime Georgia Democratic Congressman John Lewis. Representative Marcia Fudge of Ohio and CBS News political contributor and Democratic strategist Antjuan Seawright joined CBSN to discuss Lewis’ legacy.

Rep. Clyburn: If Trump wants to honor John Lewis, this is what he needs to do

Jul 18, 2020 CNN

CNN’s Ana Cabrera discusses the loss of Congressman John Lewis with one of his longtime friends and colleagues, House Majority Whip James Clyburn (D-SC). #CNN #News

Georgia congressman John Lewis dead at 80

Jul 18, 2020 ABC News

Lewis was a driving force of courage and determination in the civil rights movement.

Civil rights legend Rep. John Lewis dead at 80

Jul 18, 2020 CNN

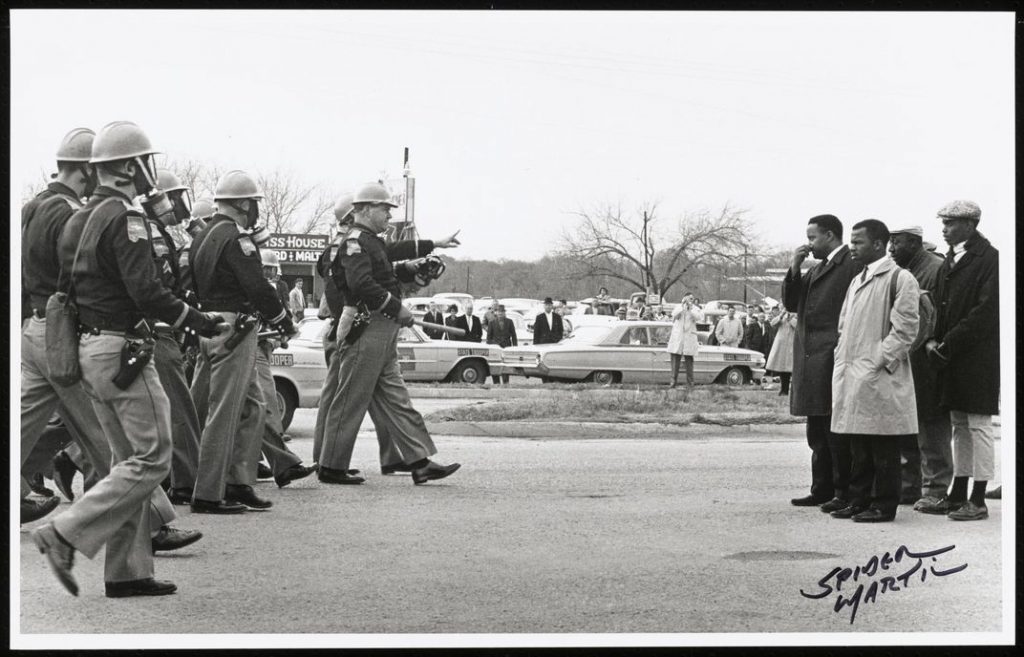

John Robert Lewis, the son of sharecroppers who survived a brutal beating by police during a landmark 1965 march in Selma, Alabama, to become a towering figure of the civil rights movement and a longtime US congressman, has died after a six-month battle with cancer. He was 80. Lewis, a Democrat who served as the US representative for Georgia’s 5th congressional district for more than three decades, was widely seen as a moral conscience of Congress because of his decades-long embodiment of nonviolent fight for civil rights. His passionate oratory was backed by a long record of action that included, by his count, more than 40 arrests while demonstrating against racial and social injustice. A follower and colleague of Martin Luther King Jr., he participated in lunch counter sit-ins, joined the Freedom Riders in challenging segregated buses and — at the age of 23 — was a keynote speaker at the historic 1963 March on Washington. “Sometimes when I look back and think about it, how did we do what we did? How did we succeed? We didn’t have a website. We didn’t have a cellular telephone,” Lewis has said of the civil rights movement. “But I felt when we were sitting in at those lunch counter stools, or going on the Freedom Ride, or marching from Selma to Montgomery, there was a power and a force. God Almighty was there with us.” Lewis has said King inspired his activism. Angered by the unfairness of the Jim Crow South, he launched what he called “good trouble” with organized protests and sit-ins. In the early 1960s, he was a Freedom Rider, challenging segregation at interstate bus terminals across the South and in the nation’s capital. “We do not want our freedom gradual; we want to be free now,” he said at the time. At age 25, Lewis helped lead a march for voting rights on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, where he and other marchers were met by heavily armed state and local police who attacked them with clubs, fracturing Lewis’ skull. Images from that “Bloody Sunday” shocked the nation and galvanized support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. “I gave a little blood on that bridge,” he said years later. “I thought I was going to die. I thought I saw death.” Despite the attack and other beatings, Lewis never lost his activist spirit, taking it from protests to politics. He was elected to the Atlanta city council in 1981, then to Congress six years later. #JohnLewis #CNN #News

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lzm0KfBNhBE

Nightly News Full Broadcast (July 18th)

Jul 18, 2020 NBC News

Congressman and civil rights giant John Lewis dies at age 80, Florida and Texas hospitals overwhelmed as coronavirus cases surge, and President Trump gives mixed messaging on mask debate.

In the Room: John Lewis and Krista Tippett

Mar 28, 2013

Rep. John Lewis and BGN: “March: Book One” | Talks at Google

Oct 28, 2014 Talks at Google

The Black Googler Network (BGN) and Talks at Google were honored to host Congressman John Lewis. Rep. Lewis is a Presidential Medal of Freedom winner. He stopped by to discuss his recently-published graphic novel: March: Book One. March is a vivid first-hand account of his dedication to the struggle for civil and human rights

Congressman John Lewis Speaks at Tisch College

Apr 14, 2016 Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life

On April 5, 2016, U.S. Congressman and civil rights hero John Lewis delivered the 4th Alan D. Solomont Lecture at Tufts University, with support from the Tisch College Distinguished Speaker Series. Congressman Lewis shared stories from the Freedom Rides and the march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, extolled the philosophy of nonviolence, and encouraged a new generation to continue the fight for justice and equality.

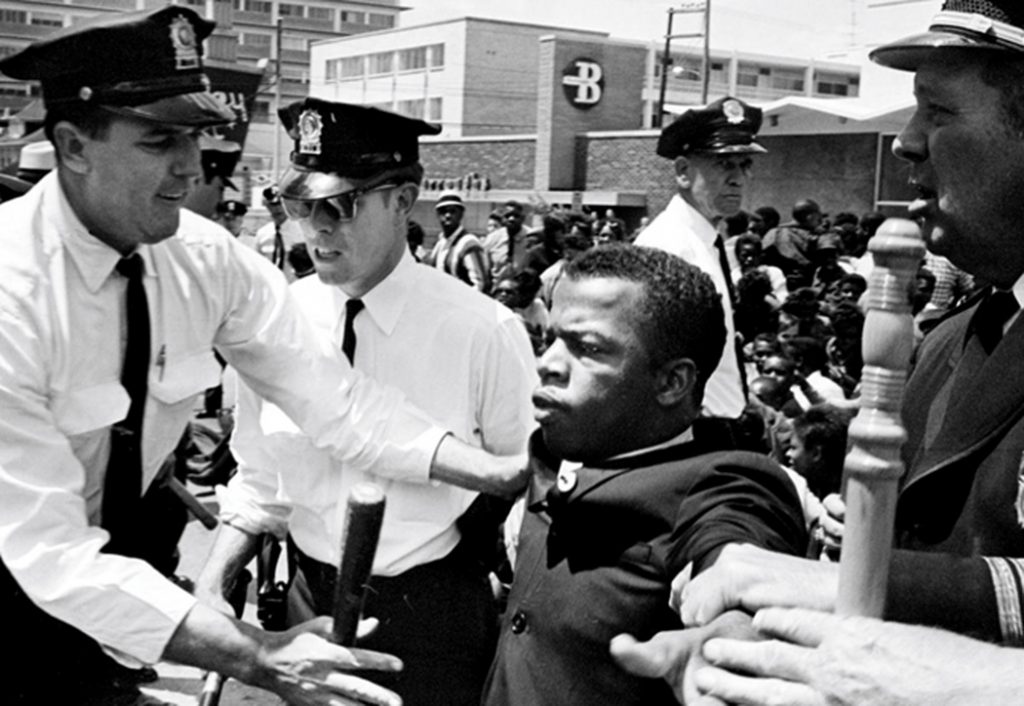

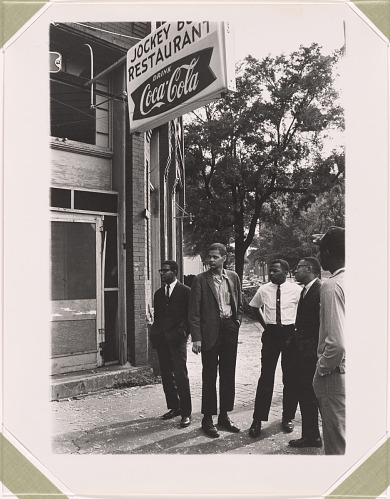

John Lewis and Two Others Attacked at South Carolina Greyhound Bus Terminal| EJI, A History of Racial Justice MAY 9, 2020

On May 9, 1961, 21-year-old John Lewis, a young black civil rights activist, was severely beaten by a mob at the Rock Hill, South Carolina, Greyhound bus terminal. A few days earlier, Lewis and twelve Freedom Riders — seven black and six white — had left Washington, D.C., on a Greyhound bus headed to New Orleans. They sat interracially on the bus, planning to test a Supreme Court ruling that made segregation in interstate transportation illegal.

On May 9, 1961, 21-year-old John Lewis, a young black civil rights activist, was severely beaten by a mob at the Rock Hill, South Carolina, Greyhound bus terminal. A few days earlier, Lewis and twelve Freedom Riders — seven black and six white — had left Washington, D.C., on a Greyhound bus headed to New Orleans. They sat interracially on the bus, planning to test a Supreme Court ruling that made segregation in interstate transportation illegal.

By EJI Staff, EJI

Featured Image, PBS

Full article @ EJI, A History of Racial Justice

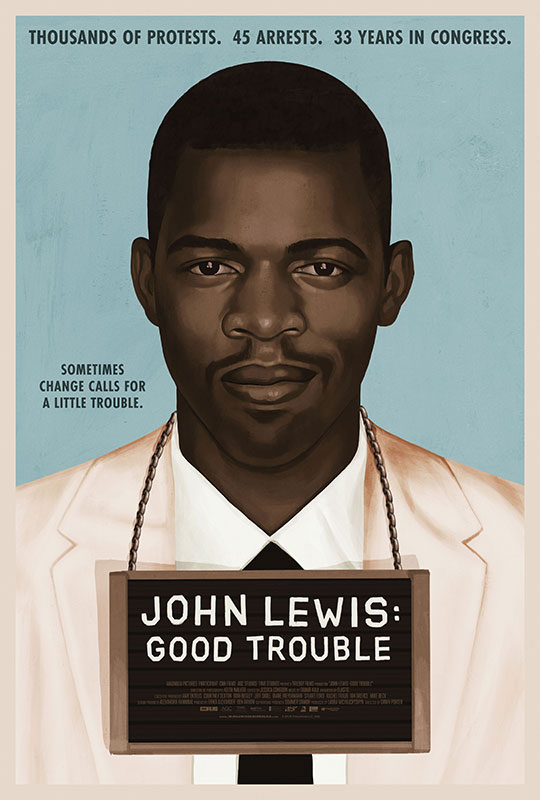

https://nmaahc.si.edu/event/premier%E2%80%94john-lewis-good-trouble

Premier—John Lewis: Good Trouble

Date & Time

Saturday, June 27, 20206:00 pm to 8:00 pm

Location

African American History and Culture Museum

Virtual

Event Type

Films, Webcasts & Online

Cost

Free

GET TICKETS OR REGISTER(LINK IS EXTERNAL)

About this Event

Director Dawn Porter uses interviews and rare archival footage in her highly anticipated documentary entitled “John Lewis: Good Trouble.” A Magnolia Pictures and Participant release, the film chronicles the Georgia U.S. Congressman Lewis’ 60-plus years of social activism and legislative action on issues ranging from voting rights to immigration. Drawing on present-day interviews with Lewis, now 80 years old, Porter explores his childhood and inspiring family as well as his fateful meeting with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1957. In addition to her interviews with Lewis and his family, the film features interviews with a variety of political figures including Ayanna Pressley, Elijah Cummings, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Stacy Abrams, Jim Clyburn, Nancy Pelosi, and Eric Holder. A post screening discussion includes a conversation between Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch and Dawn Porter. The film will be released in theaters and on demand July 3. A limited number of the tickets will be available via the museum’s website on:

Co-Sponsors

Magnolia Films

John Lewis Is a Personal Symbol for a Historic Period

By Bryant Rollins Nov. 14, 1976

Credit…The New York Times Archives

Credit…The New York Times Archives

See the article in its original context from

November 14, 1976, Page 176Buy Reprints

John Lewis is a name from the past in the American civil rights movement, but it is also a name from the present, and perhaps the future, of American politics. Mr. Lewis, normally the most self?effacing of men, was prideful and expansive last week in declaring, as others have, that Southern black voters had been responsible for electing a Southern white politician President.

The claim is no more susceptible to final proof, or disproof, than others that have been and will be made; the closeness of the vote encourages the claims but also means all the votes are vital for Jimmy Carter. Yet Mr. Lewis has more evidence on his side than most: There has been a peaceful political revolution in the South, and Mr. Carter has been its first beneficiary. For instance:

In 1960 there were only about a million blacks registered to vote in the 11 states of the Deep South; there are now four million. In 1960 there were fewer than 50 black elected officials; now there are about 2,000, In 1960 any attempt by large numbers blacks to register to vote, or to organize politically in any effective way, was met with violent resistance by whites; today, black political participation is an accepted reality.

Last week, black voters apparently contributed substantially to Mr. Carter’s margin of victory in all the states of the Deep South except Virginia, which President Ford won. In Georgia, whites and blacks alike favored Mr. Carter. Elsewhere in the South, about 55 percent of the white voters preferred President Ford, but over 95 percent of the black voters favored Mr. Carter.

Even that near unanimity would not have mattered had it involved the insignificant black vote of the past. This year, 63 percent of registered Southerners, black and white, voted, compared with 53 percent nationwide.

John Lewis is not the only person responsible for that. Last Sunday in Atlanta he was one of about 100 blacks and whites who attended a reunion of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—the student?based activist group of the 1960’s—that Mr. Lewis once headed.

But there were few in that group, now largely over the antimagical age of 30 and mundanely middle class, who constitute a better individual symbol—both a barometer and a progenitor—of black progress from productive protest against a racist social system to productive groundwork within the political system.

He was born the third in a family of 10 children and raised near Troy, the seat of Pike County, Alabama. When he was three years old, in 1943, his sharecropper father took his life savings—$300—and bought his own farm. There, oh 100 acres of mostly cotton in the center of predominantly white farming country, John Lewis was raised in the rigidly segregated environment that prevailed.

That segregation began to break down with the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955, led by Dr. Martin Luther King. The boycott also provoked Mr. Lewis’ interest in nonviolent social protest. He says now:

“It was inconceivable to us that black people would openly defy white people in the state of Alabama. To see hundreds of thousands of Montgomery blacks refusing to ride the buses, walking together to work, and forming car pools, was a moving experience. We used to lie in the dark at night listening to the news on the radio.”

Mr. Lewis, now 36, is a Baptist minister, a vocation he inclined to when he was 10; Reverend King’s leadership in Montgomery gave form to Mr. Lewis’ aspirations. He decided then not to seek an institutional church connection, but to work for social change in the deep South, and to adopt a Gandhian based, nonviolent social action as his philosophy for life.

He gained a reputation during the civil rights movement years as a mystical person who had a sometimes irrational faith in his own survivability. One leader who knew him well said: “Some leaders, even the toughest, would occasionally finesse a situation where they knew they were going to get beaten or jailed. John never did that. He always went full force into the fray.”

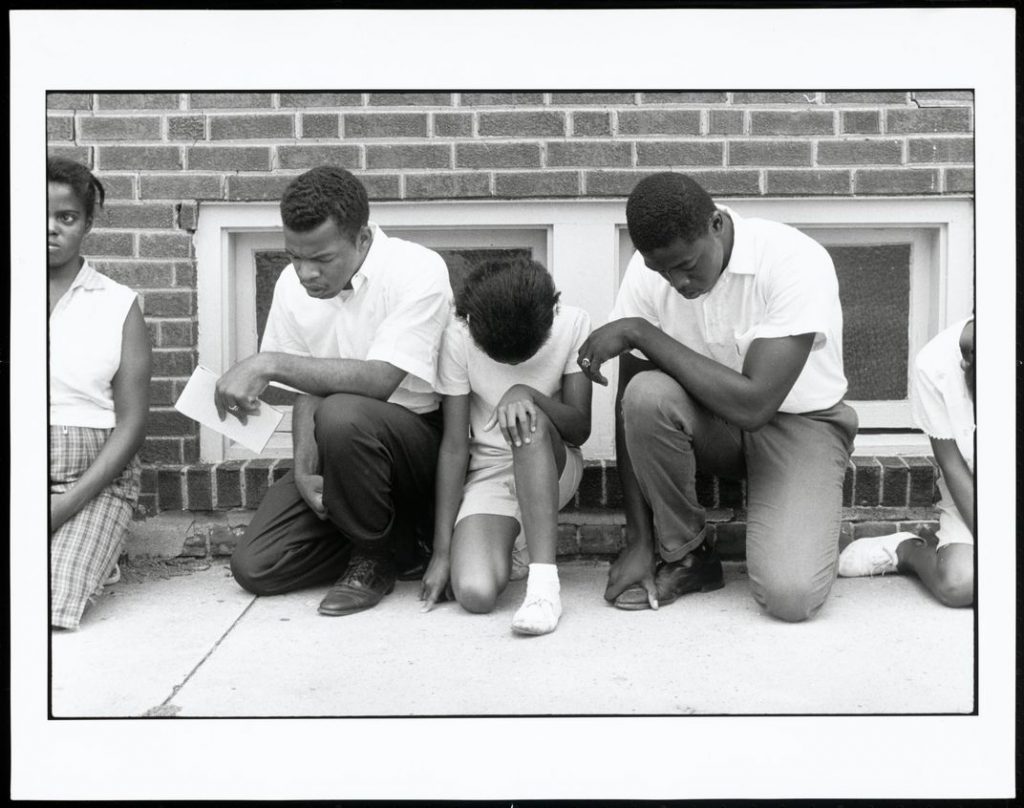

The spirit of nonviolent protest generated by Dr. King and his associates grew into the most powerful social movement since the mass labor organizing of the 30’s. The white South was at first bemused, then angered and outraged, and the outrage was often expressed violently. Demonstrators were brutally beaten, jailed and some were killed.

Between 1960 and 1966, Mr. Lewis was arrested 40 times. His longest term in prison was 31 days in the Parchman Penitentiary in Mississippi. He was beaten on many occasions, several times almost beaten to death. In May of 1961, he was left unconscious in a pool of his own blood outside the Greyhound Bus Terminal in Montgomery after he and a score of others were attacked by hundreds of whites; the protestors had been trying to desegregate the bus terminal. Mr. Lewis was saved by a white Southern law enforcement official. He was seriously injured again in March of 1965 at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala.

The crash of racial barriers falling throughont the South was audible in the North; what was not so audible were the cries of personal pain that many of the civil rights workers suffered. John Lewis’ two concussions, at Montgomery and at Selma, and numerous other beatings, left him with severe, numbing pains in his head. Only in recent years have neurological specialists in Boston and New York helped to relieved some of his suffering.

If the personal pain went unremarked, the movement in which it was incurred did not. The 1964 public accommodations act resulted from national outrage at the beatings of the Freedom Riders; the 1964 Voting Rights Act followed the violence of state troopers in Selma. That legislation is what enabled Mr. Lewis to change the manner in which he pursued his devotional life.

He had been the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee from its formation 1963 until 1966. He was involved in other civil rights projects until 1970, when he began the work that bore its sweetest fruit on November 2nd.

As head of the Voter Education Project in Atlanta, a nonprofit organization funded mostly by foundation grants and with a full?time staff of 10, Mr. Lewis pursues tactics he used in the civil rights movement, and his organization’s activities during the recent campaign were typical.

He worked with Julian Bond and other prominent blacks for six months in the 11 states of the Deep South to register voters, sponsor voter education workshops and help get out the vote on Election Day. More than 100 local organizations were financed.

The voter education project spent about $500,000 much of it in grants of $1,000 to $2,000 to local chapters of the Urban League or the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, to local church groups of civic organizations. Nearly all of the groups were black; a few were biracial, and some were Spanish?speaking and native American. None were white.

Mr. Lewis stresses that the work was “nonpartisan.” For tax purposes his organization cannot conduct partisan political drives. It is clear, however, that most of those who register are Democrats.

The voter education project also produced radio and television spots, hundreds of posters and thousands of leaflets promoting voter registration. One of the most popular posters included a saying used in earlier voter registration drives by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee: “Hands that once picked cotton now can pick a President.”

lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.

— Twitter @repjohnlewis June 2018

National Portrait Gallery: John R, Lewis

National Portrait Gallery: John R, Lewis

National Portrait Gallery: John R, Lewis and Julian Bond

National Portrait Gallery: John R, Lewis and Julian Bond

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Two Minute Warning

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Two Minute Warning

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Disgusting

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Disgusting

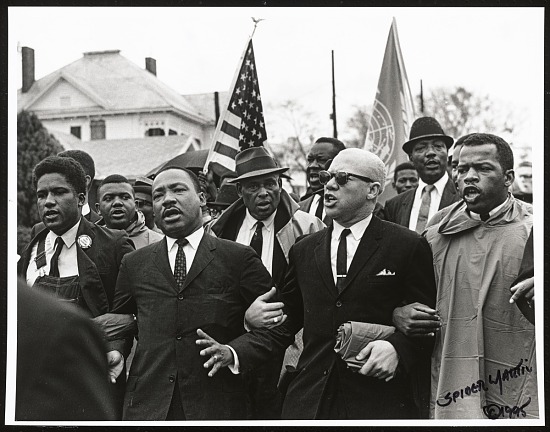

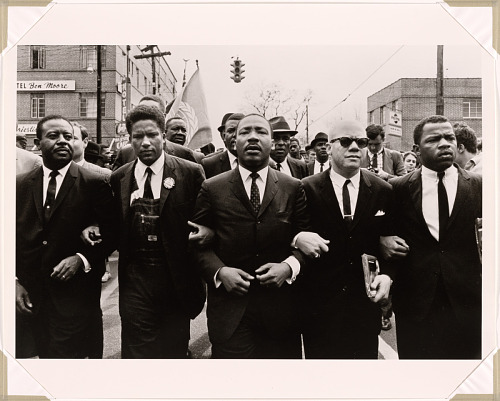

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Dr. King Holding Arms; Dr. King, John Lewis, Reverend Jessie Douglas, and James Farmer

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Dr. King Holding Arms; Dr. King, John Lewis, Reverend Jessie Douglas, and James Farmer

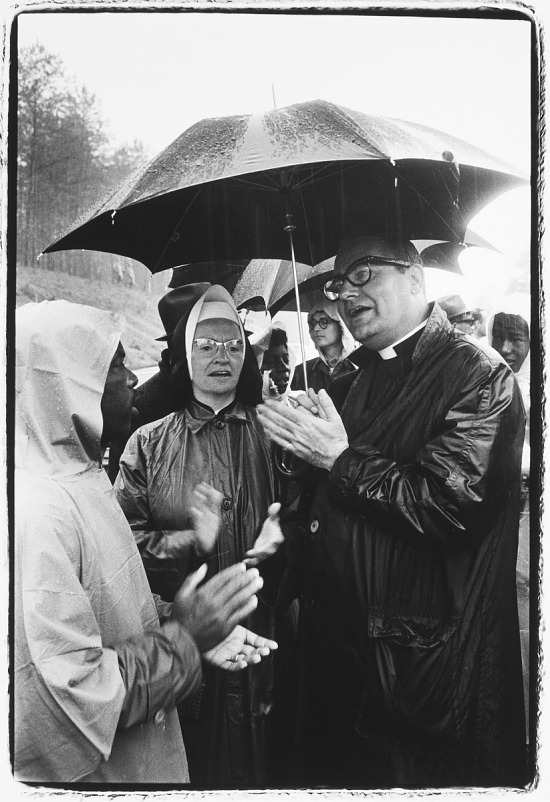

National Museum of African American History and Culture: John Lewis, Sister Mary Leoline, and Father Theodore Gill, Selma to Montgomery March

National Museum of African American History and Culture: John Lewis, Sister Mary Leoline, and Father Theodore Gill, Selma to Montgomery March

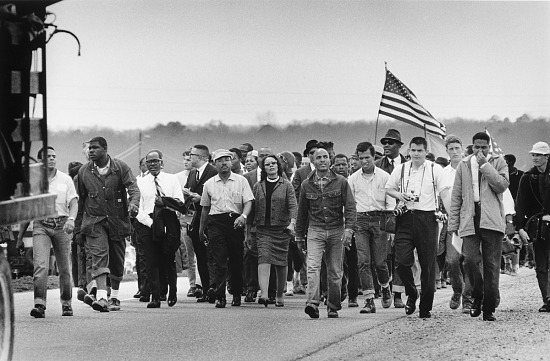

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Other leaders on Highway 80, Selma to Montgomery March

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Other leaders on Highway 80, Selma to Montgomery March

National Portrait Gallery: Martin Luther King, Marching for Voting Rights With John Lewis, Reverend Jessie Douglas, James Forman, and Ralph Abernathy, Selma, 1965

National Portrait Gallery: Martin Luther King, Marching for Voting Rights With John Lewis, Reverend Jessie Douglas, James Forman, and Ralph Abernathy, Selma, 1965

National Museum of African American History and Culture: John Lewis and Sister Mary Leoline Hand in Hand, Selma to Montgomery March

National Museum of African American History and Culture: John Lewis and Sister Mary Leoline Hand in Hand, Selma to Montgomery March

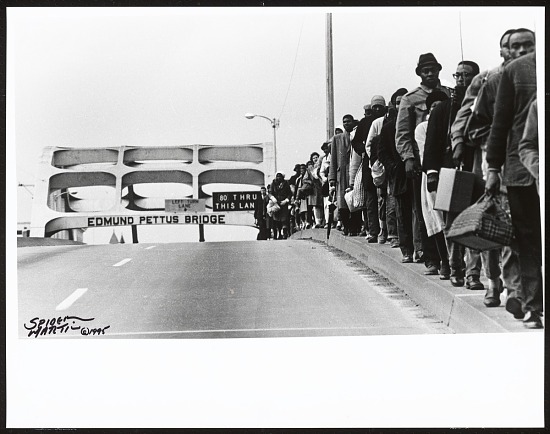

National Museum of African American History and Culture: The Edmund Pettus Bridge

National Museum of African American History and Culture: The Edmund Pettus Bridge

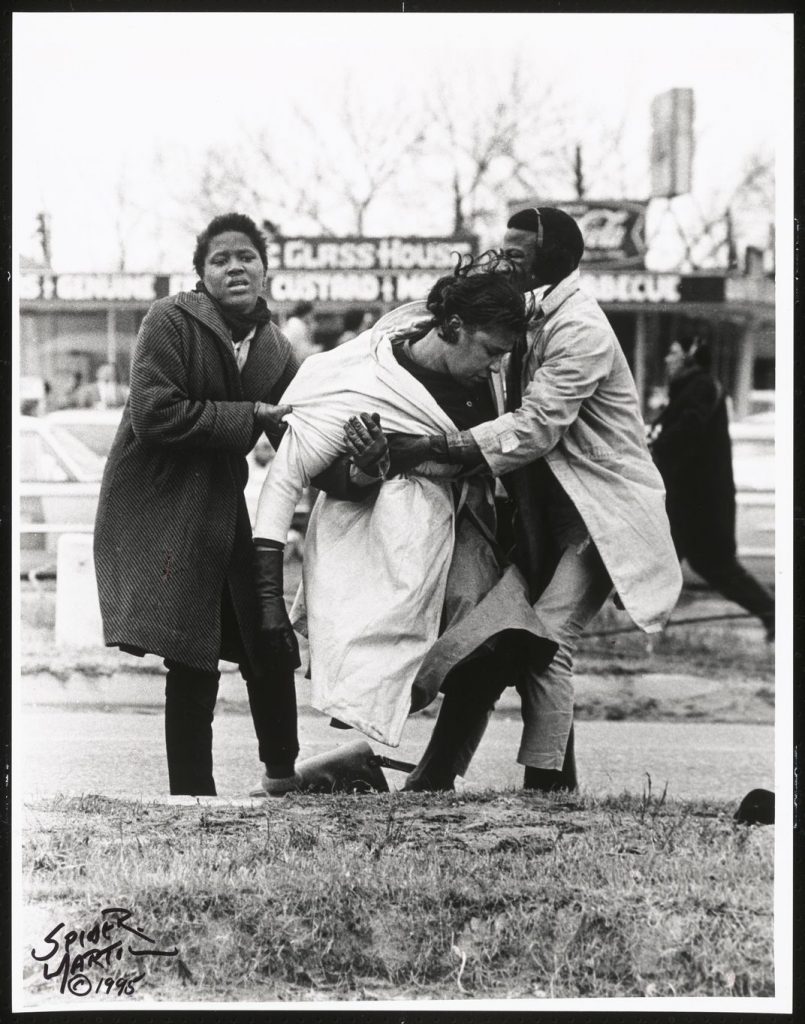

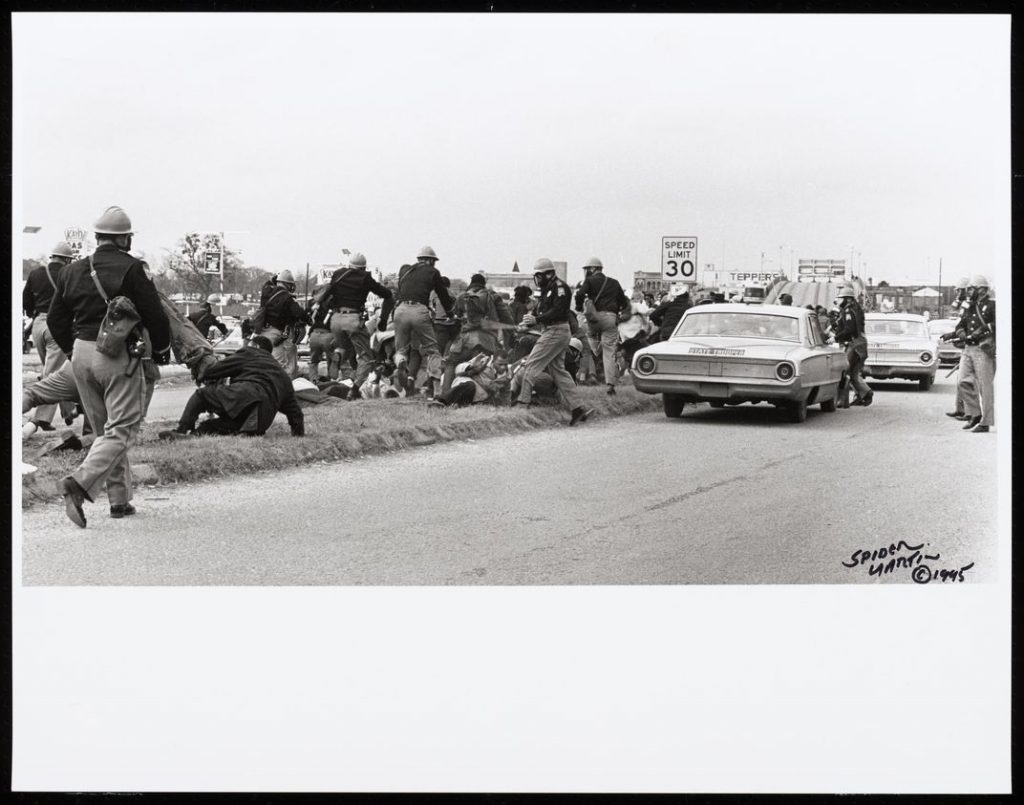

National Museum of African American History and Culture: The Beating

National Museum of African American History and Culture: The Beating

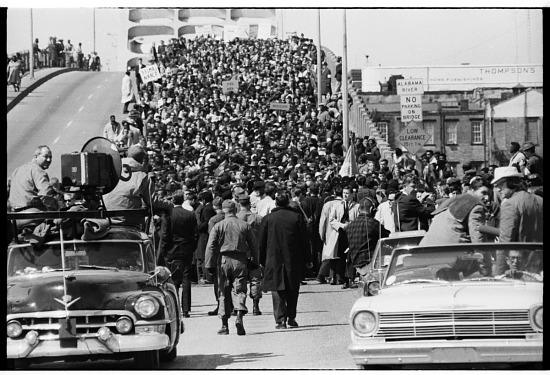

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Marchers Crossing The Edmund Pettus Bridge

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Marchers Crossing The Edmund Pettus Bridge

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Selma to Montgomery March

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Selma to Montgomery March

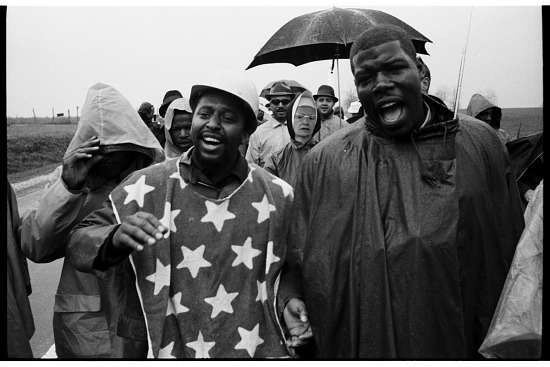

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Singing in the Rain, Selma to Montgomery March

National Museum of African American History and Culture: Singing in the Rain, Selma to Montgomery March

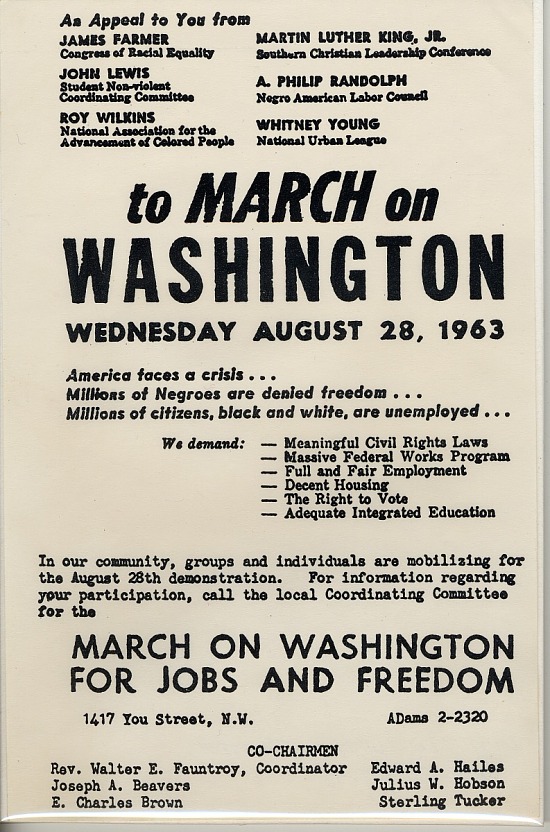

National Museum of American History: March on Washington Handbill

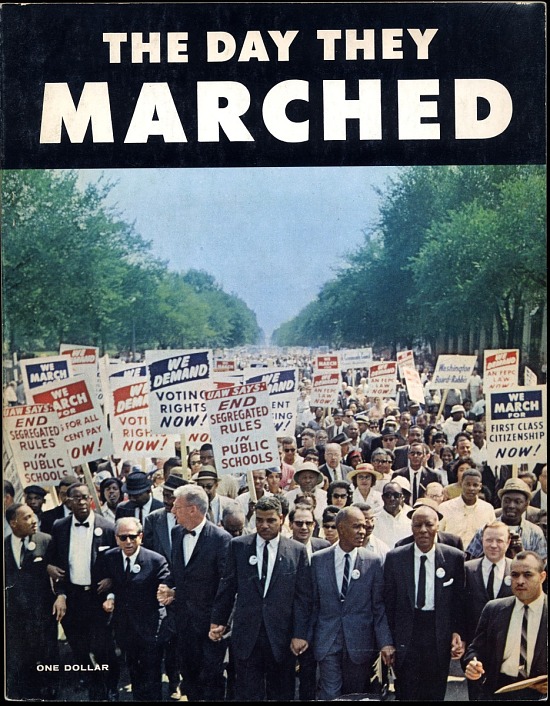

National Museum of American History Book: The Day They Marched

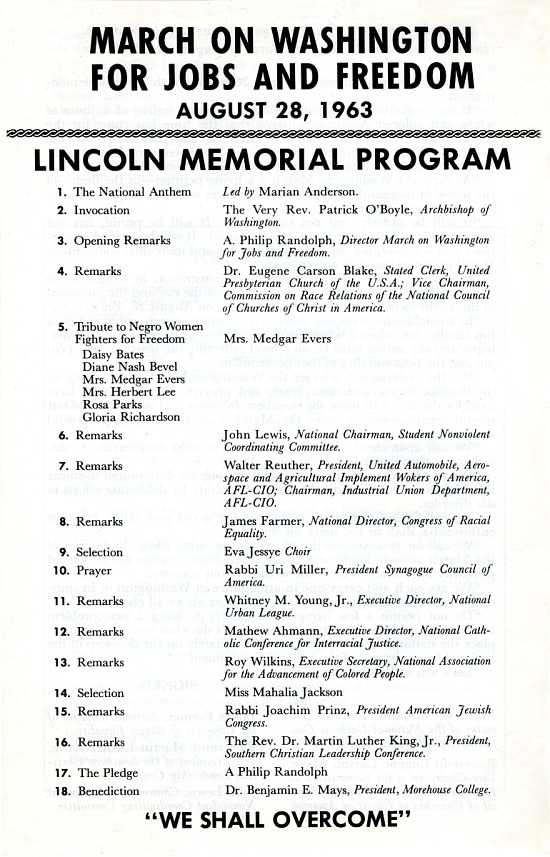

National Museum of American History: Program, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Leave a Reply