Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and The Swallowtail Butterfly in Ing & John’s Backyard Garden

I love my little garden in our backyard, in Downtown Newark, New Jersey. I feel calm and peaceful seeing green leaves with beautiful flowers in different shade of color. The bees are buzzing and dancing around different flowers for the juicy nectar. I saw some Monarch Butterflies on difference occasions. On Monday, July 27, 2020 I was very lucky to have a large beautiful Swallowtail butterfly come to visit our garden and enjoy tasting the nectar from our butterfly bush flowers. I ran in the house to get my camcorder to record for our grandsons. One grandson is 5 months old and other just turned 5 years old.

Nature always gives us peace and happiness, if we cultivate and take care of it. Humans are part of nature. Some who cultivate their behavior and contribute their knowledge and time for the good of society thereby help humanity reach harmony and peace. Sadly, such a person just passed away. The late Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a person that we can be proud to know about. She will always be remembered and we will forever be grateful for her contributions.

I wish to dedicate my peaceful garden to the late Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, for her lifelong achievements. May she rest in peace. We will always keep her in our minds and hearts.

Ing-On Vibulbhan-Watts, Monday, September 21, 2020

Ruth Bader Ginsburg (/?be?d?r ???nzb??r?/; born Joan Ruth Bader; March 15, 1933 – September 18, 2020),[1] also known by her initials RBG, was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until her death in 2020. She was nominated by President Bill Clinton and was generally viewed as belonging to the liberal wing of the Court. Ginsburg was the second woman to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court, after Sandra Day O’Connor. During her tenure on the Court, Ginsburg authored notable majority opinions, including United States v. Virginia (1996), Olmstead v. L.C. (1999), and Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc. (2000). Following O’Connor’s retirement in 2006 and until Sonia Sotomayor joined the Court in 2009, she was the only female justice on the Supreme Court. During that time, Ginsburg became more forceful with her dissents, which were noted by legal observers and in popular culture.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg (/?be?d?r ???nzb??r?/; born Joan Ruth Bader; March 15, 1933 – September 18, 2020),[1] also known by her initials RBG, was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until her death in 2020. She was nominated by President Bill Clinton and was generally viewed as belonging to the liberal wing of the Court. Ginsburg was the second woman to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court, after Sandra Day O’Connor. During her tenure on the Court, Ginsburg authored notable majority opinions, including United States v. Virginia (1996), Olmstead v. L.C. (1999), and Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc. (2000). Following O’Connor’s retirement in 2006 and until Sonia Sotomayor joined the Court in 2009, she was the only female justice on the Supreme Court. During that time, Ginsburg became more forceful with her dissents, which were noted by legal observers and in popular culture.

Ginsburg was born and grew up in Brooklyn, New York. Her older sister died when she was a baby, and her mother died shortly before Ginsburg graduated from high school. She then earned her bachelor’s degree at Cornell University and became a wife to Martin D. Ginsburg and a mother before starting law school at Harvard, where she was one of the few women in her class. Ginsburg transferred to Columbia Law School, where she graduated tied for first in her class. Following law school, Ginsburg entered academia. She was a professor at Rutgers Law School and Columbia Law School, teaching civil procedure as one of the few women in her field.

Ginsburg was born and grew up in Brooklyn, New York. Her older sister died when she was a baby, and her mother died shortly before Ginsburg graduated from high school. She then earned her bachelor’s degree at Cornell University and became a wife to Martin D. Ginsburg and a mother before starting law school at Harvard, where she was one of the few women in her class. Ginsburg transferred to Columbia Law School, where she graduated tied for first in her class. Following law school, Ginsburg entered academia. She was a professor at Rutgers Law School and Columbia Law School, teaching civil procedure as one of the few women in her field.

Ginsburg spent a considerable part of her legal career as an advocate for gender equality and women’s rights, winning multiple arguments before the Supreme Court. She advocated as a volunteer attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union and was a member of its board of directors and one of its general counsels in the 1970s. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where she served until her appointment to the Supreme Court. Ginsburg received attention in American popular culture for her fiery liberal dissents and refusal to step down. She was playfully dubbed “The Notorious R.B.G.”, a reference to Brooklyn-born rapper The Notorious B.I.G.[2]

Ginsburg spent a considerable part of her legal career as an advocate for gender equality and women’s rights, winning multiple arguments before the Supreme Court. She advocated as a volunteer attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union and was a member of its board of directors and one of its general counsels in the 1970s. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where she served until her appointment to the Supreme Court. Ginsburg received attention in American popular culture for her fiery liberal dissents and refusal to step down. She was playfully dubbed “The Notorious R.B.G.”, a reference to Brooklyn-born rapper The Notorious B.I.G.[2]

Ginsburg died at her home in Washington, D.C., on September 18, 2020, at the age of 87, from complications of metastatic pancreatic cancer.[3][4]

Ginsburg died at her home in Washington, D.C., on September 18, 2020, at the age of 87, from complications of metastatic pancreatic cancer.[3][4]

Joan Ruth Bader was born in the New York City borough of Brooklyn, the second daughter of Celia (née Amster) and Nathan Bader, who lived in the Flatbush neighborhood. Her father was a Jewish emigrant from Odessa, Russian Empire, and her mother was born in New York to Austrian Jewish parents.[5][6][7] The Baders’ elder daughter Marylin died of meningitis at age six, when Ruth was 14 months old.[1]:3[8][9] The family called Joan Ruth “Kiki”, a nickname Marylin had given her for being “a kicky baby”.[1]:3[10] When “Kiki” started school, Celia discovered that her daughter’s class had several other girls named Joan, so Celia suggested the teacher call her daughter “Ruth” to avoid confusion.[1]:3 Although not devout, the Bader family belonged to East Midwood Jewish Center, a Conservative synagogue, where Ruth learned tenets of the Jewish faith and gained familiarity with the Hebrew language.[1]:14–15 At age 13, Ruth acted as the “camp rabbi” at a Jewish summer program at Camp Che-Na-Wah in Minerva, New York.[10]

Celia took an active role in her daughter’s education, often taking her to the library.[10] Celia had been a good student in her youth, graduating from high school at age 15, yet she could not further her own education because her family instead chose to send her brother to college. Celia wanted her daughter to get more education, which she thought would allow Ruth to become a high school history teacher.[11] Ruth attended James Madison High School, whose law program later dedicated a courtroom in her honor. Celia struggled with cancer throughout Ruth’s high school years and died the day before Ruth’s high school graduation.[10]

Celia took an active role in her daughter’s education, often taking her to the library.[10] Celia had been a good student in her youth, graduating from high school at age 15, yet she could not further her own education because her family instead chose to send her brother to college. Celia wanted her daughter to get more education, which she thought would allow Ruth to become a high school history teacher.[11] Ruth attended James Madison High School, whose law program later dedicated a courtroom in her honor. Celia struggled with cancer throughout Ruth’s high school years and died the day before Ruth’s high school graduation.[10]

Bader attended Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and was a member of Alpha Epsilon Phi.[12] While at Cornell, she met Martin D. Ginsburg at age 17.[11] She graduated from Cornell with a bachelor of arts degree in government on June 23, 1954. She was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and the highest-ranking female student in her graduating class.[12][13] Bader married Ginsburg a month after her graduation from Cornell. She and Martin moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he was stationed as a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps officer in the Army Reserve after his call-up to active duty.[11][14][13] At age 21, she worked for the Social Security Administration office in Oklahoma, where she was demoted after becoming pregnant with her first child.[9] She gave birth to a daughter in 1955.[9]

Bader attended Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and was a member of Alpha Epsilon Phi.[12] While at Cornell, she met Martin D. Ginsburg at age 17.[11] She graduated from Cornell with a bachelor of arts degree in government on June 23, 1954. She was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and the highest-ranking female student in her graduating class.[12][13] Bader married Ginsburg a month after her graduation from Cornell. She and Martin moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he was stationed as a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps officer in the Army Reserve after his call-up to active duty.[11][14][13] At age 21, she worked for the Social Security Administration office in Oklahoma, where she was demoted after becoming pregnant with her first child.[9] She gave birth to a daughter in 1955.[9]

In the fall of 1956, Ginsburg enrolled at Harvard Law School, where she was one of only nine women in a class of about 500 men.[15][16] The Dean of Harvard Law reportedly invited all the female law students to dinner at his family home and asked the female law students, including Ginsburg, “Why are you at Harvard Law School, taking the place of a man?”[a][11][17][18] When her husband took a job in New York City, Ginsburg transferred to Columbia Law School and became the first woman to be on two major law reviews: the Harvard Law Review and Columbia Law Review. In 1959, she earned her law degree at Columbia and tied for first in her class.[10][19]

In the fall of 1956, Ginsburg enrolled at Harvard Law School, where she was one of only nine women in a class of about 500 men.[15][16] The Dean of Harvard Law reportedly invited all the female law students to dinner at his family home and asked the female law students, including Ginsburg, “Why are you at Harvard Law School, taking the place of a man?”[a][11][17][18] When her husband took a job in New York City, Ginsburg transferred to Columbia Law School and became the first woman to be on two major law reviews: the Harvard Law Review and Columbia Law Review. In 1959, she earned her law degree at Columbia and tied for first in her class.[10][19]

At the start of her legal career, Ginsburg encountered difficulty in finding employment.[20][21][22] In 1960, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter rejected Ginsburg for a clerkship position due to her gender. She was rejected despite a strong recommendation from Albert Martin Sacks, who was a professor and later dean of Harvard Law School.[23][24][b] Columbia law professor Gerald Gunther also pushed for Judge Edmund L. Palmieri of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York to hire Ginsburg as a law clerk, threatening to never recommend another Columbia student to Palmieri if he did not give Ginsburg the opportunity and guaranteeing to provide the judge with a replacement clerk should Ginsburg not succeed.[9][10][25] Later that year, Ginsburg began her clerkship for Judge Palmieri, and she held the position for two years.[9][10]

From 1961 to 1963, Ginsburg was a research associate and then an associate director of the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure; she learned Swedish to co-author a book with Anders Bruzelius on civil procedure in Sweden.[26][27] Ginsburg conducted extensive research for her book at Lund University in Sweden.[28] Ginsburg’s time in Sweden also influenced her thinking on gender equality. She was inspired when she observed the changes in Sweden, where women were 20 to 25 percent of all law students; one of the judges whom Ginsburg watched for her research was eight months pregnant and still working.[11]

Her first position as a professor was at Rutgers Law School in 1963.[29] The appointment was not without its drawbacks; Ginsburg was informed she would be paid less than her male colleagues because she had a husband with a well-paid job.[22] At the time Ginsburg entered academia, she was one of fewer than 20 female law professors in the United States.[29] She was a professor of law, mainly civil procedure, at Rutgers from 1963 to 1972, receiving tenure from the school in 1969.[30][31]

Her first position as a professor was at Rutgers Law School in 1963.[29] The appointment was not without its drawbacks; Ginsburg was informed she would be paid less than her male colleagues because she had a husband with a well-paid job.[22] At the time Ginsburg entered academia, she was one of fewer than 20 female law professors in the United States.[29] She was a professor of law, mainly civil procedure, at Rutgers from 1963 to 1972, receiving tenure from the school in 1969.[30][31]

In 1970, she co-founded the Women’s Rights Law Reporter, the first law journal in the U.S. to focus exclusively on women’s rights.[32] From 1972 to 1980, she taught at Columbia Law School, where she became the first tenured woman and co-authored the first law school casebook on sex discrimination.[31] She also spent a year as a fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University from 1977 to 1978.[33]

In 1970, she co-founded the Women’s Rights Law Reporter, the first law journal in the U.S. to focus exclusively on women’s rights.[32] From 1972 to 1980, she taught at Columbia Law School, where she became the first tenured woman and co-authored the first law school casebook on sex discrimination.[31] She also spent a year as a fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University from 1977 to 1978.[33]

Ginsburg in 1977, photographed by Lynn Gilbert

Ginsburg in 1977, photographed by Lynn Gilbert

Litigation and advocacy

In 1972, Ginsburg co-founded the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and in 1973, she became the Project’s general counsel.[13] The Women’s Rights Project and related ACLU projects participated in more than three hundred gender discrimination cases by 1974. As the director of the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project, she argued six gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court between 1973 and 1976, winning five.[23] Rather than asking the court to end all gender discrimination at once, Ginsburg charted a strategic course, taking aim at specific discriminatory statutes and building on each successive victory. She chose plaintiffs carefully, at times picking male plaintiffs to demonstrate that gender discrimination was harmful to both men and women.[23][31] The laws Ginsburg targeted included those that on the surface appeared beneficial to women, but in fact reinforced the notion that women needed to be dependent on men.[23] Her strategic advocacy extended to word choice, favoring the use of “gender” instead of “sex”, after her secretary suggested the word “sex” would serve as a distraction to judges.[31] She attained a reputation as a skilled oral advocate, and her work led directly to the end of gender discrimination in many areas of the law.[34]

Ginsburg volunteered to write the brief for Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), in which the Supreme Court extended the protections of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to women.[31][35][c] In 1972, she argued before the 10th Circuit in Moritz v. Commissioner on behalf of a man who had been denied a caregiver deduction because of his gender. As amicus she argued in Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973), which challenged a statute making it more difficult for a female service member (Frontiero) to claim an increased housing allowance for her husband than for a male service member seeking the same allowance for his wife. Ginsburg argued that the statute treated women as inferior, and the Supreme Court ruled 8–1 in Frontiero’s favor.[23] The court again ruled in Ginsburg’s favor in Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (1975), where Ginsburg represented a widower denied survivor benefits under Social Security, which permitted widows but not widowers to collect special benefits while caring for minor children. She argued that the statute discriminated against male survivors of workers by denying them the same protection as their female counterparts.[37]

Ginsburg volunteered to write the brief for Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), in which the Supreme Court extended the protections of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to women.[31][35][c] In 1972, she argued before the 10th Circuit in Moritz v. Commissioner on behalf of a man who had been denied a caregiver deduction because of his gender. As amicus she argued in Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973), which challenged a statute making it more difficult for a female service member (Frontiero) to claim an increased housing allowance for her husband than for a male service member seeking the same allowance for his wife. Ginsburg argued that the statute treated women as inferior, and the Supreme Court ruled 8–1 in Frontiero’s favor.[23] The court again ruled in Ginsburg’s favor in Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (1975), where Ginsburg represented a widower denied survivor benefits under Social Security, which permitted widows but not widowers to collect special benefits while caring for minor children. She argued that the statute discriminated against male survivors of workers by denying them the same protection as their female counterparts.[37]

Ginsburg filed an amicus brief and sat with counsel at oral argument for Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190 (1976), which challenged an Oklahoma statute that set different minimum drinking ages for men and women.[23][37] For the first time, the court imposed what is known as intermediate scrutiny on laws discriminating based on gender, a heightened standard of Constitutional review.[23][37][38] Her last case as an attorney before the Supreme Court was in 1978 Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979), which challenged the validity of voluntary jury duty for women, on the ground that participation in jury duty was a citizen’s vital governmental service and therefore should not be optional for women. At the end of Ginsburg’s oral argument, then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist asked Ginsburg, “You won’t settle for putting Susan B. Anthony on the new dollar, then?”[39] Ginsburg said she considered responding, “We won’t settle for tokens,” but instead opted not to answer the question.[39]

Ginsburg filed an amicus brief and sat with counsel at oral argument for Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190 (1976), which challenged an Oklahoma statute that set different minimum drinking ages for men and women.[23][37] For the first time, the court imposed what is known as intermediate scrutiny on laws discriminating based on gender, a heightened standard of Constitutional review.[23][37][38] Her last case as an attorney before the Supreme Court was in 1978 Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979), which challenged the validity of voluntary jury duty for women, on the ground that participation in jury duty was a citizen’s vital governmental service and therefore should not be optional for women. At the end of Ginsburg’s oral argument, then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist asked Ginsburg, “You won’t settle for putting Susan B. Anthony on the new dollar, then?”[39] Ginsburg said she considered responding, “We won’t settle for tokens,” but instead opted not to answer the question.[39]

Legal scholars and advocates credit Ginsburg’s body of work with making significant legal advances for women under the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.[31][23] Taken together, Ginsburg’s legal victories discouraged legislatures from treating women and men differently under the law.[31][23][37] She continued to work on the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project until her appointment to the Federal Bench in 1980.[31] Later, colleague Antonin Scalia praised Ginsburg’s skills as an advocate. “She became the leading (and very successful) litigator on behalf of women’s rights—the Thurgood Marshall of that cause, so to speak.” This was a comparison that had first been made by former Solicitor General Erwin Griswold who was also her former professor and dean at Harvard Law School, in a speech given in 1985.[40][41][d]

Legal scholars and advocates credit Ginsburg’s body of work with making significant legal advances for women under the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.[31][23] Taken together, Ginsburg’s legal victories discouraged legislatures from treating women and men differently under the law.[31][23][37] She continued to work on the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project until her appointment to the Federal Bench in 1980.[31] Later, colleague Antonin Scalia praised Ginsburg’s skills as an advocate. “She became the leading (and very successful) litigator on behalf of women’s rights—the Thurgood Marshall of that cause, so to speak.” This was a comparison that had first been made by former Solicitor General Erwin Griswold who was also her former professor and dean at Harvard Law School, in a speech given in 1985.[40][41][d]

Ginsburg with President Jimmy Carter in 1980

Ginsburg with President Jimmy Carter in 1980

U.S. Court of Appeals

Ginsburg was nominated by President Jimmy Carter on April 14, 1980, to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit vacated by Judge Harold Leventhal after his death.[30] She was confirmed by the United States Senate on June 18, 1980, and received her commission later that day.[30] Her service terminated on August 9, 1993, due to her elevation to the United States Supreme Court.[30][42][43] During her time as a judge on the DC Circuit, Ginsburg often found consensus with her colleagues including conservatives Robert H. Bork and Antonin Scalia.[44][45] Her time on the court earned her a reputation as a “cautious jurist” and a moderate.[46] David S. Tatel replaced her after Ginsburg’s appointment to the Supreme Court.[47]

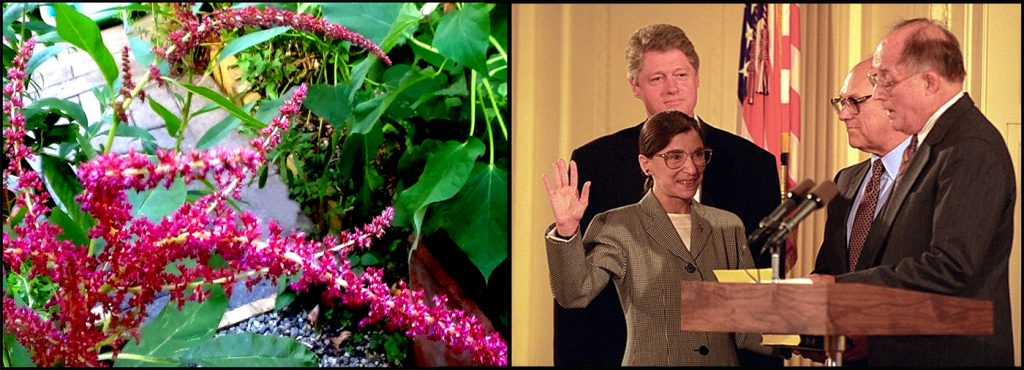

Chief Justice William Rehnquist swearing in Ginsburg as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, as her husband Martin Ginsburg and President Clinton watch

Chief Justice William Rehnquist swearing in Ginsburg as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, as her husband Martin Ginsburg and President Clinton watch

Supreme Court

Nomination and confirmation

Ginsburg officially accepting the nomination from President Bill Clinton on June 14, 1993

President Bill Clinton nominated Ginsburg as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court on June 14, 1993, to fill the seat vacated by retiring Justice Byron White. She was recommended to Clinton by then–U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno,[19] after a suggestion by Utah Republican Senator Orrin Hatch.[48] At the time of her nomination, Ginsburg was viewed as a moderate. Clinton was reportedly looking to increase the court’s diversity, which Ginsburg did as the only Jewish justice since the 1969 resignation of Justice Abe Fortas. She was the second female and the first Jewish female justice of the Supreme Court.[46][49][50] She eventually became the longest-serving Jewish justice.[51] The American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary rated Ginsburg as “well qualified”, its highest possible rating for a prospective justice.[52]

During her testimony before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary as part of the confirmation hearings, Ginsburg refused to answer questions about her view on the constitutionality of some issues such as the death penalty as it was an issue she might have to vote on if it came before the court.[53]

During her testimony before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary as part of the confirmation hearings, Ginsburg refused to answer questions about her view on the constitutionality of some issues such as the death penalty as it was an issue she might have to vote on if it came before the court.[53]

At the same time, Ginsburg did answer questions about some potentially controversial issues. For instance, she affirmed her belief in a constitutional right to privacy and explained at some length her personal judicial philosophy and thoughts regarding gender equality.[54]:15–16 Ginsburg was more forthright in discussing her views on topics about which she had previously written.[53] The United States Senate confirmed her by a 96–3 vote on August 3, 1993,[e][30] She received her commission on August 5, 1993[30] and took her judicial oath on August 10, 1993.[56]

Ginsburg’s name was later invoked during the confirmation process of John Roberts. Ginsburg herself was not the first nominee to avoid answering certain specific questions before Congress,[f] and as a young attorney in 1981 Roberts had advised against Supreme Court nominees’ giving specific responses.[57] Nevertheless, some conservative commentators and Senators invoked the phrase “Ginsburg precedent” to defend his demurrers.[52][57] In a September 28, 2005, speech at Wake Forest University, Ginsburg said Roberts’ refusal to answer questions during his Senate confirmation hearings on some cases was “unquestionably right”.[58]

Ginsburg’s name was later invoked during the confirmation process of John Roberts. Ginsburg herself was not the first nominee to avoid answering certain specific questions before Congress,[f] and as a young attorney in 1981 Roberts had advised against Supreme Court nominees’ giving specific responses.[57] Nevertheless, some conservative commentators and Senators invoked the phrase “Ginsburg precedent” to defend his demurrers.[52][57] In a September 28, 2005, speech at Wake Forest University, Ginsburg said Roberts’ refusal to answer questions during his Senate confirmation hearings on some cases was “unquestionably right”.[58]

Ginsburg characterized her performance on the court as a cautious approach to adjudication.[59] She argued in a speech shortly before her nomination to the court that “[m]easured motions seem to me right, in the main, for constitutional as well as common law adjudication. Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped, experience teaches, may prove unstable.”[60] Legal scholar Cass Sunstein characterized Ginsburg as a “rational minimalist”, a jurist who seeks to build cautiously on precedent rather than pushing the Constitution towards her own vision.[61]:10–11

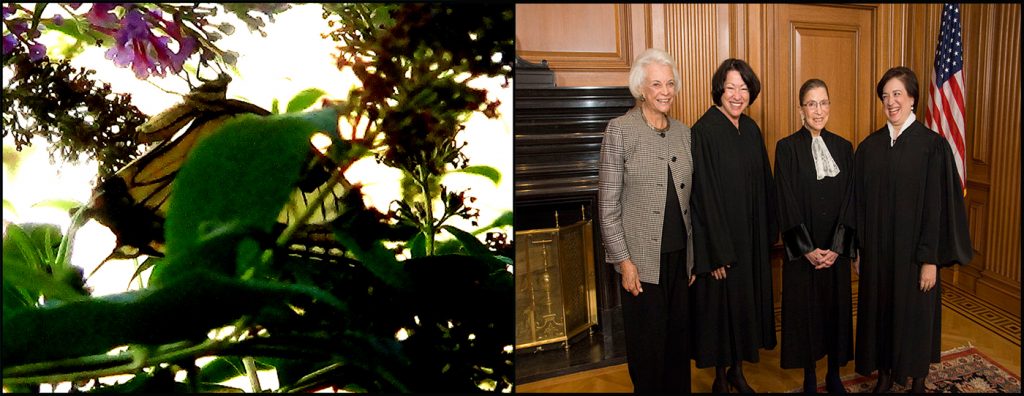

Sandra Day O’Connor, Sonia Sotomayor, Ginsburg, and Elena Kagan, October 1, 2010. O’Connor is not wearing a robe because she was retired from the court when the picture was taken.

Sandra Day O’Connor, Sonia Sotomayor, Ginsburg, and Elena Kagan, October 1, 2010. O’Connor is not wearing a robe because she was retired from the court when the picture was taken.

The retirement of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in 2006 left Ginsburg as the only woman on the court.[62][g] Linda Greenhouse of The New York Times referred to the subsequent 2006–2007 term of the court as “the time when Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg found her voice, and used it”.[64] The term also marked the first time in Ginsburg’s history with the court where she read multiple dissents from the bench, a tactic employed to signal more intense disagreement with the majority.[64]

With the retirement of Justice John Paul Stevens, Ginsburg became the senior member of what was sometimes referred to as the court’s “liberal wing”.[31][65][66] When the court split 5–4 along ideological lines and the liberal justices were in the minority, Ginsburg often had the authority to assign authorship of the dissenting opinion because of her seniority.[65][h] Ginsburg was a proponent of the liberal dissenters speaking “with one voice” and, where practicable, presenting a unified approach to which all the dissenting justices can agree.[31][65]

Ginsburg authored the court’s opinion in United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996), which struck down the Virginia Military Institute‘s (VMI) male-only admissions policy as violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. VMI is a prestigious, state-run, military-inspired institution that did not admit women. For Ginsburg, a state actor such as VMI could not use gender to deny women the opportunity to attend VMI with its unique educational methods.[68] Ginsburg emphasized that the government must show an “exceedingly persuasive justification” to use a classification based on sex.[69]

Commissioned portrait of Ginsburg in 2000

Commissioned portrait of Ginsburg in 2000

Ginsburg dissented in the court’s decision on Ledbetter v. Goodyear, 550 U.S. 618 (2007), a case where plaintiff Lilly Ledbetter filed a lawsuit against her employer claiming pay discrimination based on her gender under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In a 5–4 decision, the majority interpreted the statute of limitations as starting to run at the time of every pay period, even if a woman did not know she was being paid less than her male colleague until later. Ginsburg found the result absurd, pointing out that women often do not know they are being paid less, and therefore it was unfair to expect them to act at the time of each paycheck. She also called attention to the reluctance women may have in male-dominated fields to making waves by filing lawsuits over small amounts, choosing instead to wait until the disparity accumulates.[70] As part of her dissent, Ginsburg called on Congress to amend Title VII to undo the court’s decision with legislation.[71] Following the election of President Barack Obama in 2008, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, making it easier for employees to win pay discrimination claims, became law.[72][73] Ginsburg was credited with helping to inspire the law.[71][73]

Ginsburg discussed her views on abortion and gender equality in a 2009 New York Times interview, in which she said about abortion “[t]he basic thing is that the government has no business making that choice for a woman.”[74] Although Ginsburg consistently supported abortion rights and joined in the court’s opinion striking down Nebraska‘s partial-birth abortion law in Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914 (2000), on the 40th anniversary of the court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), she criticized the decision in Roe as terminating a nascent democratic movement to liberalize abortion laws which might have built a more durable consensus in support of abortion rights.[75] Ginsburg was in the minority for Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007), a 5–4 decision upholding restrictions on partial birth abortion. In her dissent, Ginsburg opposed the majority’s decision to defer to legislative findings that the procedure was not safe for women. Ginsburg focused her ire on the way Congress reached its findings and with the veracity of the findings.[76] Joining the majority for Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. 15-274 (2016), a case which struck down parts of a 2013 Texas law regulating abortion providers, Ginsburg also authored a short concurring opinion which was even more critical of the legislation at issue.[77] She asserted the legislation was not aimed at protecting women’s health, as Texas had said, but rather to impede women’s access to abortions.[76][77]

Although Ginsburg did not author the majority opinion, she was credited with influencing her colleagues on the case Safford Unified School District v. Redding, 557 U.S. 364 (2009).[78] The court ruled that a school went too far in ordering a 13-year-old female student to strip to her bra and underpants so female officials could search for drugs.[78] In an interview published prior to the court’s decision, Ginsburg shared her view that some of her colleagues did not fully appreciate the effect of a strip search on a 13-year-old girl. As she said, “They have never been a 13-year-old girl.”[79] In an 8–1 decision, the court agreed that the school’s search went too far and violated the Fourth Amendment and allowed the student’s lawsuit against the school to go forward. Only Ginsburg and Stevens would have allowed the student to sue individual school officials as well.[78]

In Herring v. United States, 555 U.S. 135 (2009), Ginsburg dissented from the court’s decision not to suppress evidence due to a police officer’s failure to update a computer system. In contrast to Roberts’ emphasis on suppression as a means to deter police misconduct, Ginsburg took a more robust view on the use of suppression as a remedy for a violation of a defendant’s Fourth Amendment rights. Ginsburg viewed suppression as a way to prevent the government from profiting from mistakes, and therefore as a remedy to preserve judicial integrity and respect civil rights.[80]:308 She also rejected Roberts’ assertion that suppression would not deter mistakes, contending making police pay a high price for mistakes would encourage them to take greater care.[80]:309

Ginsburg advocated the use of foreign law and norms to shape U.S. law in judicial opinions, a view rejected by some of her conservative colleagues. Ginsburg supported using foreign interpretations of law for persuasive value and possible wisdom, not as precedent which the court is bound to follow.[81] Ginsburg expressed the view that consulting international law is a well-ingrained tradition in American law, counting John Henry Wigmore and President John Adams as internationalists.[82] Ginsburg’s own reliance on international law dated back to her time as an attorney; in her first argument before the court, Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), she cited two German cases.[83] In her concurring opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003), a decision upholding Michigan Law School’s affirmative action admissions policy, Ginsburg noted there was accord between the notion that affirmative action admissions policies would have an end point and agrees with international treaties designed to combat racial and gender-based discrimination.[82]

Portrait of Ginsburg, c.? 2006

Portrait of Ginsburg, c.? 2006

Other activities

At his request, Ginsburg administered the oath of office to Vice President Al Gore for a second term during the second inauguration of Bill Clinton on January 20, 1997.[84] She was the third woman to administer an inaugural oath of office.[85] Ginsburg is believed to have been the first Supreme Court justice to officiate at a same-sex wedding, performing the August 31, 2013, ceremony of Kennedy Center President Michael Kaiser and John Roberts, a government economist.[86] Earlier that summer, the court had bolstered same-sex marriage rights in two separate cases.[87][88] Ginsburg believed the issue being settled led same-sex couples to ask her to officiate as there was no longer the fear of compromising rulings on the issue.[87]

The Supreme Court bar formerly inscribed its certificates “in the year of our Lord”, which some Orthodox Jews opposed, and asked Ginsburg to object to. She did so, and due to her objection, Supreme Court bar members have since been given other choices of how to inscribe the year on their certificates.[89]

Despite their ideological differences, Ginsburg considered Scalia her closest colleague on the court. The two justices often dined together and attended the opera.[90] In addition to befriending modern composers, including Tobias Picker,[91][92] in her spare time, Ginsburg appeared in several operas in non-speaking supernumerary roles such as Die Fledermaus (2003) and Ariadne auf Naxos (1994 and 2009 with Scalia),[93] and spoke lines penned by herself in The Daughter of the Regiment (2016).[94]

Despite their ideological differences, Ginsburg considered Scalia her closest colleague on the court. The two justices often dined together and attended the opera.[90] In addition to befriending modern composers, including Tobias Picker,[91][92] in her spare time, Ginsburg appeared in several operas in non-speaking supernumerary roles such as Die Fledermaus (2003) and Ariadne auf Naxos (1994 and 2009 with Scalia),[93] and spoke lines penned by herself in The Daughter of the Regiment (2016).[94]

In January 2012, Ginsburg went to Egypt for four days of discussions with judges, law school faculty, law school students, and legal experts.[95][96] In an interview with Al Hayat TV, she said the first requirement of a new constitution should be that it would “safeguard basic fundamental human rights like our First Amendment“. Asked if Egypt should model its new constitution on those of other nations, she said Egypt should be “aided by all Constitution-writing that has gone on since the end of World War II”, and cited the United States Constitution and Constitution of South Africa as documents she might look to if drafting a new constitution. She said the U.S. was fortunate to have a constitution authored by “very wise” men but said that in the 1780s, no women were able to participate directly in the process, and slavery still existed in the U.S.[97]

In January 2012, Ginsburg went to Egypt for four days of discussions with judges, law school faculty, law school students, and legal experts.[95][96] In an interview with Al Hayat TV, she said the first requirement of a new constitution should be that it would “safeguard basic fundamental human rights like our First Amendment“. Asked if Egypt should model its new constitution on those of other nations, she said Egypt should be “aided by all Constitution-writing that has gone on since the end of World War II”, and cited the United States Constitution and Constitution of South Africa as documents she might look to if drafting a new constitution. She said the U.S. was fortunate to have a constitution authored by “very wise” men but said that in the 1780s, no women were able to participate directly in the process, and slavery still existed in the U.S.[97]

During three separate interviews in July 2016, Ginsburg criticized presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, telling The New York Times and the Associated Press that she did not want to think about the possibility of a Trump presidency. She joked that she might consider moving to New Zealand.[98][99] She later apologized for commenting on the presumptive Republican nominee, calling her remarks “ill advised”.[100]

During three separate interviews in July 2016, Ginsburg criticized presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, telling The New York Times and the Associated Press that she did not want to think about the possibility of a Trump presidency. She joked that she might consider moving to New Zealand.[98][99] She later apologized for commenting on the presumptive Republican nominee, calling her remarks “ill advised”.[100]

Ginsburg speaking at a naturalization ceremony at the National Archives in 2018

Ginsburg speaking at a naturalization ceremony at the National Archives in 2018

Ginsburg’s first book, My Own Words published by Simon & Schuster, was released October 4, 2016.[101] The book debuted on The New York Times Best Seller List for hardcover nonfiction at No. 12.[102] While promoting her book in October 2016 during an interview with Katie Couric, Ginsburg responded to a question about Colin Kaepernick choosing not to stand for the national anthem at sporting events by calling the protest “really dumb”. She later apologized for her criticism calling her earlier comments “inappropriately dismissive and harsh” and noting she had not been familiar with the incident and should have declined to respond to the question.[103][104][105]

In 2018, Ginsburg expressed her support for the #MeToo movement, which encourages women to speak up about their experiences with sexual harassment.[106] She told an audience, “It’s about time. For so long women were silent, thinking there was nothing you could do about it, but now the law is on the side of women, or men, who encounter harassment and that’s a good thing.”[106] She also reflected on her own experiences with gender discrimination and sexual harassment, including a time when a chemistry professor at Cornell unsuccessfully attempted to trade her exam answers for sex.[106]

In 2018, Ginsburg expressed her support for the #MeToo movement, which encourages women to speak up about their experiences with sexual harassment.[106] She told an audience, “It’s about time. For so long women were silent, thinking there was nothing you could do about it, but now the law is on the side of women, or men, who encounter harassment and that’s a good thing.”[106] She also reflected on her own experiences with gender discrimination and sexual harassment, including a time when a chemistry professor at Cornell unsuccessfully attempted to trade her exam answers for sex.[106]

Martin and Ruth Ginsburg at a White House event, 2009

Martin and Ruth Ginsburg at a White House event, 2009

Personal life

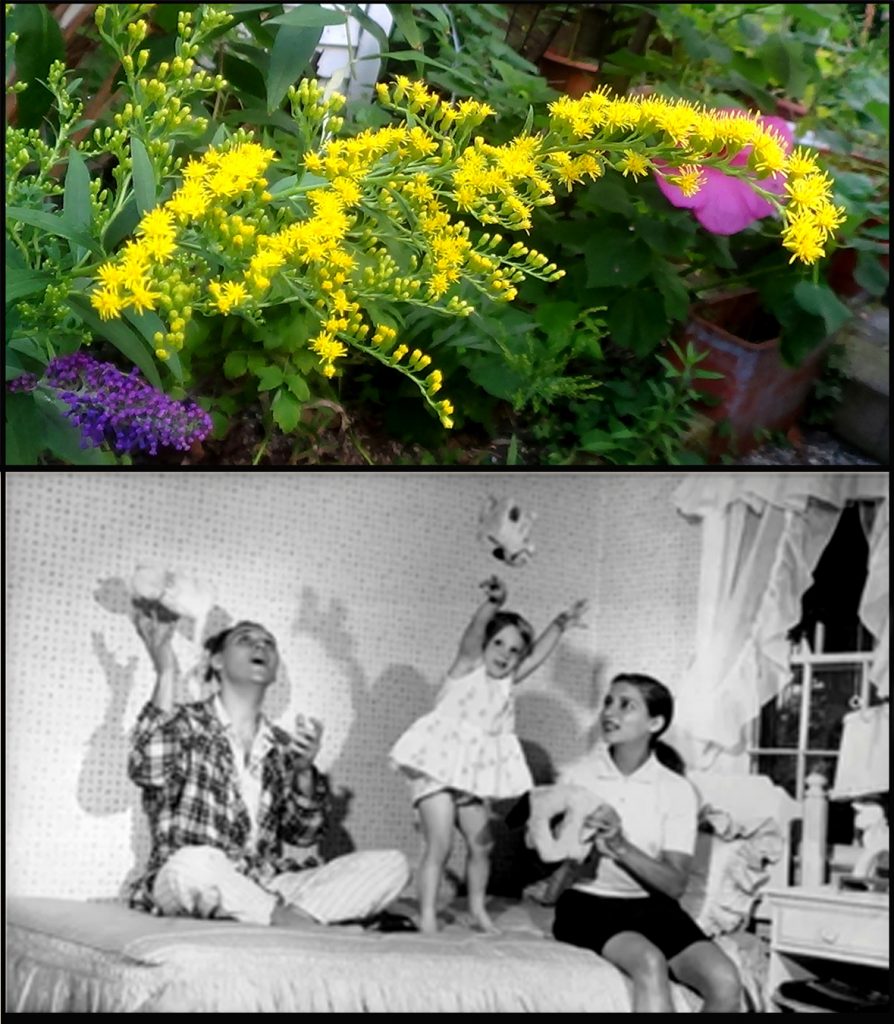

A few days after Bader graduated from Cornell, she married Martin D. Ginsburg, who later became an internationally prominent tax attorney practicing at Weil, Gotshal & Manges. Upon her accession to the D.C. Circuit, the couple moved from New York to Washington, D.C., where her husband became professor of law at Georgetown University Law Center. Their daughter, Jane C. Ginsburg (b. 1955), is a professor at Columbia Law School. Their son, James Steven Ginsburg (b. 1965), is the founder and president of Cedille Records, a classical music recording company based in Chicago, Illinois. Ginsburg was a grandmother of four.[107]

Ginsburg with her husband Martin and their daughter Jane in 1958 copyright AP

Ginsburg with her husband Martin and their daughter Jane in 1958 copyright AP

After the birth of their daughter, Ginsburg’s husband was diagnosed with testicular cancer. During this period, Ginsburg attended class and took notes for both of them, typing her husband’s dictated papers and caring for their daughter and her sick husband—all while making the Harvard Law Review. They celebrated their 56th wedding anniversary on June 23, 2010. Martin Ginsburg died of complications from metastatic cancer on June 27, 2010.[108] They spoke publicly of being in a shared earning/shared parenting marriage including in a speech Martin Ginsburg wrote and had intended to give before his death that Ruth Bader Ginsburg delivered posthumously.[109]

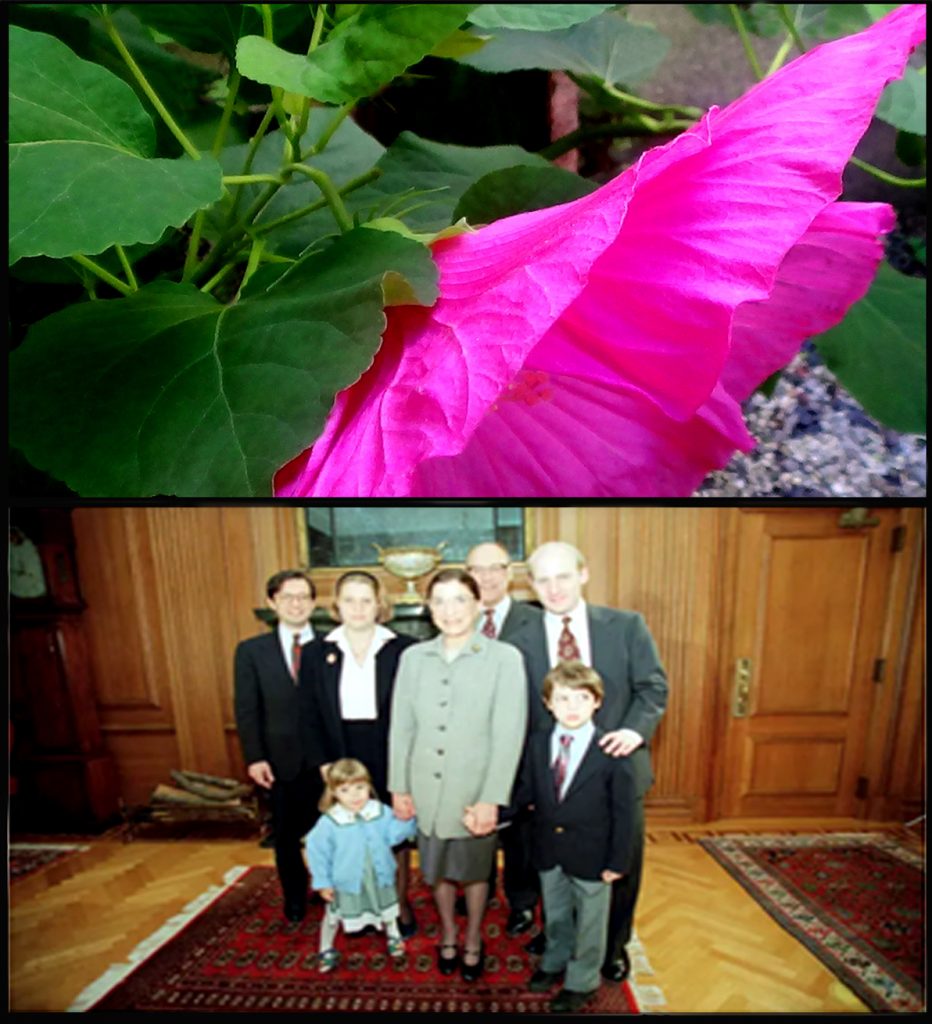

Ginsburg poses for the camera while holding hands with her grandchildren Clara and Paul Spera in 1993. Behind her are, from left, son-in-law George Spera, daughter Jane Ginsburg, husband Martin and son James Ginsburg (copyright Doug Mills/AP)

Ginsburg poses for the camera while holding hands with her grandchildren Clara and Paul Spera in 1993. Behind her are, from left, son-in-law George Spera, daughter Jane Ginsburg, husband Martin and son James Ginsburg (copyright Doug Mills/AP)

Bader was a non-observant Jew.[110] In March 2015, Ginsburg and Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt released “The Heroic and Visionary Women of Passover”, an essay highlighting the roles of five key women in the saga: “These women had a vision leading out of the darkness shrouding their world. They were women of action, prepared to defy authority to make their vision a reality bathed in the light of the day.”[111] In addition, she decorated her chambers with an artist’s rendering of the Hebrew phrase from Deuteronomy, “Zedek, zedek, tirdof,” (“Justice, justice shall you pursue”) as a reminder of her heritage and professional responsibility.[112]

Bader was a non-observant Jew.[110] In March 2015, Ginsburg and Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt released “The Heroic and Visionary Women of Passover”, an essay highlighting the roles of five key women in the saga: “These women had a vision leading out of the darkness shrouding their world. They were women of action, prepared to defy authority to make their vision a reality bathed in the light of the day.”[111] In addition, she decorated her chambers with an artist’s rendering of the Hebrew phrase from Deuteronomy, “Zedek, zedek, tirdof,” (“Justice, justice shall you pursue”) as a reminder of her heritage and professional responsibility.[112]

Bader was a non-observant Jew.[110] In March 2015, Ginsburg and Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt released “The Heroic and Visionary Women of Passover”, an essay highlighting the roles of five key women in the saga: “These women had a vision leading out of the darkness shrouding their world. They were women of action, prepared to defy authority to make their vision a reality bathed in the light of the day.”[111] In addition, she decorated her chambers with an artist’s rendering of the Hebrew phrase from Deuteronomy, “Zedek, zedek, tirdof,” (“Justice, justice shall you pursue”) as a reminder of her heritage and professional responsibility.[112]

Ginsburg had a collection of lace jabots from around the world.[113][114] She said in 2014 she had a particular jabot she wore when issuing her dissents (black with gold embroidery and faceted stones) as well as another she wore when issuing majority opinions (crocheted yellow and cream with crystals), which was a gift from her law clerks.[113][114] Her favorite jabot (woven with white beads) was from Cape Town, South Africa.[113]

In 1999, Ginsburg was diagnosed with colon cancer, the first of five[115] bouts of cancer. She underwent surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy. During the process, she did not miss a day on the bench.[116] Ginsburg was physically weakened by the cancer treatment, and she began working with a personal trainer. Bryant Johnson, a former Army reservist attached to the Special Forces, trained Ginsburg twice weekly in the justices-only gym at the Supreme Court.[117][118] Ginsburg saw her physical fitness improve after her first bout with cancer; she was able to complete 20 push-ups in a session before her 80th birthday.[117][119]

Nearly a decade after her first bout with cancer, Ginsburg again underwent surgery on February 5, 2009, this time for pancreatic cancer.[120][121] Ginsburg had a tumor that was discovered at an early stage.[120] She was released from a New York City hospital on February 13 and returned to the bench when the Supreme Court went back into session on February 23, 2009.[122][123][124] After experiencing discomfort while exercising in the Supreme Court gym in November 2014, she had a stent placed in her right coronary artery.[125][126]

Ginsburg’s next hospitalization helped her detect another round of cancer.[127] On November 8, 2018, Ginsburg fell in her office at the Supreme Court, fracturing three ribs, for which she was hospitalized.[128] An outpouring of public support followed.[129][130] Although the day after her fall, Ginsburg’s nephew revealed she had already returned to official judicial work after a day of observation,[131] a CT scan of her ribs following her November 8 fall showed cancerous nodules in her lungs.[127] On December 21, Ginsburg underwent a left-lung lobectomy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to remove the nodules.[127] For the first time since joining the Court more than 25 years earlier, Ginsburg missed oral argument on January 7, 2019, while she recuperated.[132] She returned to the Supreme Court on February 15 to participate in a private conference with other justices in her first appearance at the court since her cancer surgery in December 2018.[133]

Ginsburg’s next hospitalization helped her detect another round of cancer.[127] On November 8, 2018, Ginsburg fell in her office at the Supreme Court, fracturing three ribs, for which she was hospitalized.[128] An outpouring of public support followed.[129][130] Although the day after her fall, Ginsburg’s nephew revealed she had already returned to official judicial work after a day of observation,[131] a CT scan of her ribs following her November 8 fall showed cancerous nodules in her lungs.[127] On December 21, Ginsburg underwent a left-lung lobectomy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to remove the nodules.[127] For the first time since joining the Court more than 25 years earlier, Ginsburg missed oral argument on January 7, 2019, while she recuperated.[132] She returned to the Supreme Court on February 15 to participate in a private conference with other justices in her first appearance at the court since her cancer surgery in December 2018.[133]

Months later in August 2019, the Supreme Court announced that Ginsburg had recently completed three weeks of focused radiation treatment to ablate a tumor found in her pancreas over the summer.[134] By January 2020, Ginsburg was cancer-free. By February 2020, Ginsberg was not cancer free but it was not released to the public. [135] However, by May 2020, Ginsburg was once again receiving treatment for a recurrence of cancer.[136] She reiterated her position that she “would remain a member of the court as long as I can do the job full steam”, adding that she remained fully able to do so.[137][138]

Months later in August 2019, the Supreme Court announced that Ginsburg had recently completed three weeks of focused radiation treatment to ablate a tumor found in her pancreas over the summer.[134] By January 2020, Ginsburg was cancer-free. By February 2020, Ginsberg was not cancer free but it was not released to the public. [135] However, by May 2020, Ginsburg was once again receiving treatment for a recurrence of cancer.[136] She reiterated her position that she “would remain a member of the court as long as I can do the job full steam”, adding that she remained fully able to do so.[137][138]

When John Paul Stevens retired in 2010, Ginsburg became the oldest justice on the court at age 77.[139] Despite rumors that she would retire because of advancing age, poor health, and the death of her husband,[140][141] she denied she was planning to step down. In an August 2010 interview, Ginsburg said her work on the court was helping her cope with the death of her husband.[139] She also expressed a wish to emulate Justice Louis Brandeis‘ service of nearly 23 years, which she achieved in April 2016.[139][142] She stated she had a new “model” to emulate in former colleague Justice John Paul Stevens, who retired at age 90 after nearly 35 years on the bench.[142]

During the presidency of Barack Obama, some progressive attorneys and activists called for Ginsburg to retire so Obama could appoint a like-minded successor,[143][144][145] particularly while the Democratic Party held control of the U.S. Senate.[146] They mentioned Ginsburg’s age and past health issues as factors making her longevity uncertain.[144] Ginsburg rejected these pleas.[65] She affirmed her wish to remain a justice as long as she was mentally sharp enough to perform her duties.[65] Moreover, Ginsburg opined that the political climate would prevent Obama from appointing a jurist like herself.[147] At the time of her death in September 2020, Ginsburg was, at age 87, the fourth-oldest serving U.S. Supreme Court Justice in the history of the country.[148]

During the presidency of Barack Obama, some progressive attorneys and activists called for Ginsburg to retire so Obama could appoint a like-minded successor,[143][144][145] particularly while the Democratic Party held control of the U.S. Senate.[146] They mentioned Ginsburg’s age and past health issues as factors making her longevity uncertain.[144] Ginsburg rejected these pleas.[65] She affirmed her wish to remain a justice as long as she was mentally sharp enough to perform her duties.[65] Moreover, Ginsburg opined that the political climate would prevent Obama from appointing a jurist like herself.[147] At the time of her death in September 2020, Ginsburg was, at age 87, the fourth-oldest serving U.S. Supreme Court Justice in the history of the country.[148]

Candles left on the steps of the Supreme Court following the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Candles left on the steps of the Supreme Court following the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Ginsburg died from complications of pancreatic cancer on September 18, 2020, at age 87.[149][150][4] One day before her death, Ginsburg was honored on Constitution Day and was awarded the 2020 Liberty Medal by the National Constitution Center.[151] It was reported that she will be interred in Arlington National Cemetery next to her husband Martin D. Ginsburg.[152][153]

Main article: 2020 United States Supreme Court vacancy

Ginsburg’s death created a vacancy on the Supeme Court in a presidential election year.[154] Days before her death, Ginsburg dictated in a statement through her granddaughter Clara Spera, “My most fervent wish is that I will not be replaced until a new president is installed.”[155] Four years earlier, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell refused to allow the Senate to consider President Obama’s nominee to replace Justice Scalia, citing the Thurmond rule, an inconsistently applied practice which posits that the senate will not confirm a Supreme Court nominee during a presidential election year except under certain circumstances.[156]

Ginsburg receiving the LBJ Liberty & Justice for All Award from Lynda Johnson Robb and Luci Baines Johnson at the Library of Congress in January 2020

Ginsburg receiving the LBJ Liberty & Justice for All Award from Lynda Johnson Robb and Luci Baines Johnson at the Library of Congress in January 2020

Recognition

In 2002, Ginsburg was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.[157] Ginsburg was named one of 100 Most Powerful Women (2009),[158] one of Glamour magazine’s Women of the Year 2012,[159] and one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people (2015).[160] She was awarded honorary Doctor of Laws degrees by Willamette University (2009),[161] Princeton University (2010),[162] and Harvard University (2011).[163]

In 2009, Ginsberg received a Lifetime Achievement Award from Scribes–The American Society of Legal Writers.[164]

In 2013, a painting featuring the four female justices to have served as justices on the Supreme Court (Ginsburg, Sandra Day O’Connor, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan) was unveiled at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.[165][166]

Researchers at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History gave a species of praying mantis the name Ilomantis ginsburgae after Ginsburg. The name was given because the neck plate of the Ilomantis ginsburgae bears a resemblance to a jabot, which Ginsburg was known for wearing. Moreover, the new species was identified based upon the female insect’s genitalia instead of based upon the male of the species. The researchers noted that the name was a nod to Ginsburg’s fight for gender equality.[167][168]

Researchers at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History gave a species of praying mantis the name Ilomantis ginsburgae after Ginsburg. The name was given because the neck plate of the Ilomantis ginsburgae bears a resemblance to a jabot, which Ginsburg was known for wearing. Moreover, the new species was identified based upon the female insect’s genitalia instead of based upon the male of the species. The researchers noted that the name was a nod to Ginsburg’s fight for gender equality.[167][168]

Ginsburg was the recipient of the 2019 $1 million Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture.[169] Awarded annually, the Berggruen Institute stated it recognizes “thinkers whose ideas have profoundly shaped human self-understanding and advancement in a rapidly changing world”,[170] noting Ginsburg as “a lifelong trailblazer for human rights and gender equality”.[171] Ginsburg received numerous awards including the LBJ Foundation’s Liberty & Justice for All Award, the World Peace and Liberty Award from international legal groups, and a lifetime achievement award from Diane von Furstenberg‘s foundation all in 2020 alone.[172]

The Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles created an exhibition focusing on Ginsburg’s life and career exhibition in 2019 called Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[173][174]

A poster depicting Ginsburg as “the Notorious R.B.G.” in the likeness of American rapper The Notorious B.I.G., 2018

A poster depicting Ginsburg as “the Notorious R.B.G.” in the likeness of American rapper The Notorious B.I.G., 2018

In popular culture

Ginsburg has been referred to as a “pop culture icon”.[175][176][177] Ginsburg’s profile began to rise after O’Connor’s retirement in 2006 left Ginsburg as the only serving female justice. Her increasingly fiery dissents, particularly in Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 2 (2013), led to the creation of the Notorious R.B.G. Tumblr and Internet meme comparing the justice to rapper The Notorious B.I.G.[178] The creator of the Notorious R.B.G. Tumblr, then-law student Shana Knizhnik, teamed up with MSNBC reporter Irin Carmon to turn the blog into a book titled Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[179] Released in October 2015, the book became a New York Times bestseller.[180] In 2015, Ginsburg and Scalia, known for their shared love of opera, were fictionalized in Scalia v. Ginsburg, an opera by Derrick Wang.[181]

Additionally, Ginsburg’s pop culture appeal has inspired nail art, Halloween costumes, a bobblehead doll, tattoos, t-shirts, coffee mugs, and a children’s coloring book among other things.[179][182][183][184] She appears in both a comic opera and a workout book.[184] Musician Jonathan Mann also made a song using part of her Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. dissent.[185] Ginsburg admitted to having a “large supply” of Notorious R.B.G. t-shirts, which she distributed as gifts.[186]

Additionally, Ginsburg’s pop culture appeal has inspired nail art, Halloween costumes, a bobblehead doll, tattoos, t-shirts, coffee mugs, and a children’s coloring book among other things.[179][182][183][184] She appears in both a comic opera and a workout book.[184] Musician Jonathan Mann also made a song using part of her Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. dissent.[185] Ginsburg admitted to having a “large supply” of Notorious R.B.G. t-shirts, which she distributed as gifts.[186]

Since 2015, Kate McKinnon has portrayed Ginsburg on Saturday Night Live.[187] McKinnon has repeatedly reprised the role, including during a Weekend Update sketch that aired from the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland.[188][189] The segments typically feature McKinnon (as Ginsburg) lobbing insults she calls “Ginsburns” and doing a celebratory dance.[190][191] Filmmakers Betsy West and Julie Cohen created a documentary about Ginsburg, titled RBG, for CNN Films, which premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival.[192][25] In the film Deadpool 2 (2018), a photo of her is shown as Deadpool considers her for his X-Force, a team of superheroes.[193] Another film, On the Basis of Sex, focusing on Ginsburg’s career struggles fighting for equal rights, was released later in 2018; its screenplay was named to the Black List of best unproduced screenplays of 2014.[194] English actress Felicity Jones portrays Ginsburg in the film, with Armie Hammer as her husband Marty.[195] Ginsburg herself has a cameo in the film.[196] The seventh season of the sitcom New Girl features a three-year-old character named Ruth Bader Schmidt, named after Ginsburg.[197] A Lego mini-figurine of Ginsburg is shown within a brief segment of The Lego Movie 2. Ginsburg gave her blessing for the cameo, as well as to have the mini-figurine produced as part of the Lego toy sets following the film’s release in February 2019.[198] Also in 2019, Samuel Adams released a limited-edition beer called When There Are Nine, referring to Ginsburg’s well-known reply to the question about when there would be enough women on the Supreme Court.[199]

Since 2015, Kate McKinnon has portrayed Ginsburg on Saturday Night Live.[187] McKinnon has repeatedly reprised the role, including during a Weekend Update sketch that aired from the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland.[188][189] The segments typically feature McKinnon (as Ginsburg) lobbing insults she calls “Ginsburns” and doing a celebratory dance.[190][191] Filmmakers Betsy West and Julie Cohen created a documentary about Ginsburg, titled RBG, for CNN Films, which premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival.[192][25] In the film Deadpool 2 (2018), a photo of her is shown as Deadpool considers her for his X-Force, a team of superheroes.[193] Another film, On the Basis of Sex, focusing on Ginsburg’s career struggles fighting for equal rights, was released later in 2018; its screenplay was named to the Black List of best unproduced screenplays of 2014.[194] English actress Felicity Jones portrays Ginsburg in the film, with Armie Hammer as her husband Marty.[195] Ginsburg herself has a cameo in the film.[196] The seventh season of the sitcom New Girl features a three-year-old character named Ruth Bader Schmidt, named after Ginsburg.[197] A Lego mini-figurine of Ginsburg is shown within a brief segment of The Lego Movie 2. Ginsburg gave her blessing for the cameo, as well as to have the mini-figurine produced as part of the Lego toy sets following the film’s release in February 2019.[198] Also in 2019, Samuel Adams released a limited-edition beer called When There Are Nine, referring to Ginsburg’s well-known reply to the question about when there would be enough women on the Supreme Court.[199]

Chief Justice John G Roberts, front center, poses in 2018 with, back row from left, Neil Gorsuch, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Brett M Kavanaugh and, front raw from left, Stephen Breyer, Clarence Thomas, Ginsburg and Samuel Alito copyright Jim Lo Scalzo/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Chief Justice John G Roberts, front center, poses in 2018 with, back row from left, Neil Gorsuch, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Brett M Kavanaugh and, front raw from left, Stephen Breyer, Clarence Thomas, Ginsburg and Samuel Alito copyright Jim Lo Scalzo/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Image copyright THE WASHINGTON POST/GETTY

Image copyright THE WASHINGTON POST/GETTY

Ginsburg with Senators Daniel Moynihan (left) and Joe Biden in 1993

Although they were on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum, Justice Antonin Scalia (left) and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had a professional respect for each other and a personal bond. Nina Totenberg, joined by intern Anthony Palmer, joined the two at a 2015 event.

Although they were on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum, Justice Antonin Scalia (left) and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had a professional respect for each other and a personal bond. Nina Totenberg, joined by intern Anthony Palmer, joined the two at a 2015 event.

Image from Nina Totenberg

PBS NewsHour Weekend Full Episode September 19, 2020

Sep 19, 2020 PBS NewsHour

On this edition for Saturday, September 19, remembering Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg who died due to complications from Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer on Friday — and the political battle her election-year vacancy brings. Hari Sreenivasan anchors from New York. Stream your PBS favorites with the PBS app: https://to.pbs.org/2Jb8twG Find more from PBS NewsHour at https://www.pbs.org/newshour Subscribe to our YouTube channel: https://bit.ly/2HfsCD6

Ruth Bader Ginsburg Swearing-In (1993)

Jul 8, 2016 clintonlibrary42

This is video footage of Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg being sworn in as Associate Supreme Court Justice. This footage is official public record produced by the White House Television (WHTV) crew, provided by the Clinton Presidential Library. Date: August 10, 1993 Location: East Room. White House. Washington, DC Access Restriction(s): unrestricted Use Restrictions(s): unrestricted Camera: White House Television (WHTV) / Main Local Identifiers: MT01028 This material is public domain, as it is a work prepared by an officer or employee of the U.S. government as part of that person’s official duties. Any usage must receive the credit “Courtesy; William J. Clinton Presidential Library,” and no exclusive rights or permissions are granted for usage.

Announcement of Ginsburg as Supreme Court Justice Nominee

Apr 23, 2012 clintonlibrary42

This is video footage of President Clinton announcing the Ruth Bader Ginsburg as Supreme Court Justice nominee. This footage is official public record produced by the White House Television (WHTV) crew, provided by the Clinton Presidential Library. Date: June 14, 1993 Location: Rose Garden. White House. Washington, DC ARC Identifier: 6037153 http://www.archives.gov/research/search/ Access Restriction(s): unrestricted Use Restrictions(s): unrestricted Camera: White House Television (WHTV) / Main Local Identifiers: MT00790 This material is public domain, as it is a work prepared by an officer or employee of the U.S. government as part of that person’s official duties. Any usage must receive the credit “Courtesy; William J. Clinton Presidential Library,” and no exclusive rights or permissions are granted for usage.

Thanks to Wikipedia for the above information

Thanks to Wikipedia for the above information

For more information please view the following link:

httphttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruth_Bader_Ginsburgs://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruth_Bader_Ginsburg

Leave a Reply